WHO KILLED STALIN

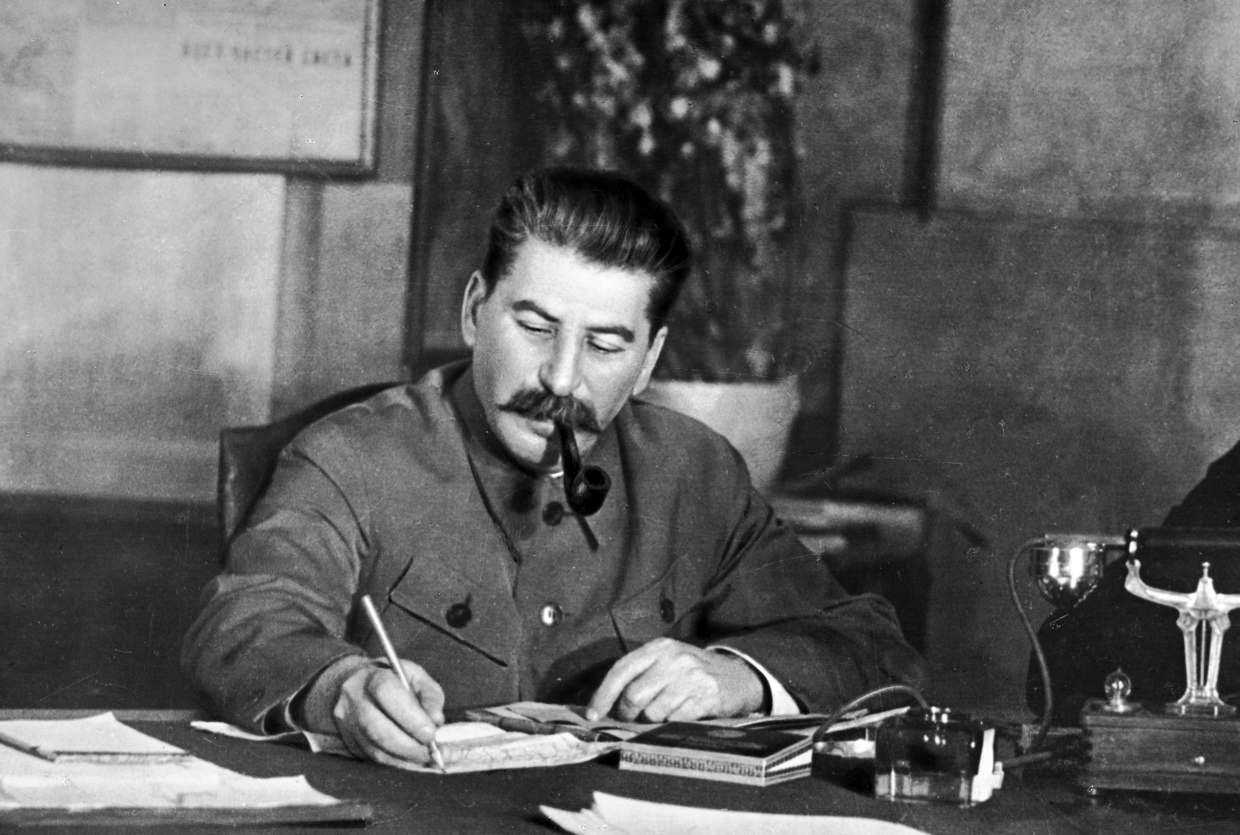

File Photo by Library of Congress/UPI

SEE STALIN

New Study Supports Idea Stalin Was Poisoned

By Michael Wines

March 5, 2003

Fifty years after Stalin died, felled by a brain hemorrhage at his dacha, an exhaustive study of long-secret Soviet records lends new weight to an old theory that he was actually poisoned, perhaps to avert a looming war with the United States.

That war may well have been closer than anyone outside the Kremlin suspected at the time, say the authors of a new book based on the records.

The 402-page book, ''Stalin's Last Crime,'' will be published later this month. Relying on a previously secret account by doctors of Stalin's final days, its authors suggest that he may have been poisoned with warfarin, a tasteless and colorless blood thinner also used as a rat killer, during a final dinner with four members of his Politburo.

They base that theory in part on early drafts of the report, which show that Stalin suffered extensive stomach hemorrhaging during his death throes. The authors state that significant references to stomach bleeding were excised from the 20-page official medical record, which was not issued until June 1953, more than three months after his death on March 5 that year.

Four Politburo members were at that dinner: Lavrenti P. Beria, then chief of the secret police; Georgi M. Malenkov, Stalin's immediate successor; Nikita S. Khrushchev, who eventually rose to the top spot; and Nikolai Bulganin.

The authors, Vladimir P. Naumov, a Russian historian, and Jonathan Brent, a Yale University Soviet scholar, suggest that the most likely suspect, if Stalin was poisoned, is Beria, for 15 years his despised minister of internal security.

You have 9 free articles remaining.Subscribe to The Times

Beria supposedly boasted of killing Stalin on May Day, two months after his death. ''I did him in! I saved all of you,'' he was quoted as telling Vyacheslav M. Molotov, another Politburo member, in Khrushchev's 1970 memoirs, ''Khrushchev Remembers.''

But Mr. Naumov and Mr. Brent dismiss Khrushchev's own account of Stalin's death, in the same memoirs, as an almost cartoonish distortion of the truth. With virtually everyone connected to the case now dead, the real story may never be known, Mr. Brent said in an interview this week.

''Some doctors are skeptical that if an autopsy were performed, that a conclusive answer to the question of whether he was poisoned could be found,'' he said. ''I personally believe that Stalin's death was not fortuitous. There are just too many arrows pointing in the other direction.''

Editors’ Picks

A Farmhouse Fantasy Tucked in the Woods of Upstate New York

Javelinas Like This? Baby, They Were Born to Run

The book, like most such volumes, paints a chilling portrait of Stalin, at once deeply paranoid and endlessly crafty, continually inventing enemies and then wiping them out as part of the terror that killed millions and kept millions more in the toil that enabled the Soviet Union to leap from czarism to the industrial age.

Yet modern Russians are torn about his memory. The latest poll of 1,600 adults by the All-Russian Public Opinion Center, released today on the eve of the 50th anniversary of his death, shows that more than half of all respondents believe Stalin's role in Russian history was positive, while only a third disagreed.

By the poll's reckoning, 27 percent of Russians judge Stalin a cruel and inhumane tyrant. But 20 percent call him wise and humane -- among them the head of the Communist Party, Gennadi Zyuganov, who today compared Stalin to ''the most grandiose figures of the Renaissance.''

Mr. Brent and Mr. Naumov, the secretary of a Russian government commission to rehabilitate victims of repression, have spent years in the archives of the K.G.B. and other Soviet organizations.

Russian officials granted them access to some documents for their latest work, which primarily traces the fabulous course of the Doctors' Plot, a supposed collusion in the late 1940's by Kremlin doctors to kill top Communist leaders.

The collusion was in fact a fabrication by Kremlin officials, acting largely on Stalin's orders. By the time Stalin disclosed the plot to a stunned Soviet populace in January 1953, he had spun it into a vast conspiracy, led by Jews under the United States' secret direction, to kill him and destroy the Soviet Union itself.

That February, the Kremlin ordered the construction of four giant prison camps in Kazakhstan, Siberia and the Arctic north, apparently in preparation for a second great terror -- this time directed at the millions of Soviet citizens of Jewish descent.

But the terror never unfolded. On March 1, 1953, two weeks after the camps were ordered built and two weeks before the accused doctors were to go on trial, Stalin collapsed at Blizhnaya, a north Moscow dacha, after the all-night dinner with his four Politburo comrades.

After four days, Stalin died, at age 73. Death was laid to a hemorrhage on the left side of his brain.

Less than a month later, the doctors previously accused of trying to kill him were abruptly exonerated and the case against them was deemed an invention of the secret police. No Jews were deported east. By year's end, Beria faced a firing squad, and Khrushchev had tempered Soviet hostility toward the United States.

In their book, Mr. Naumov and Mr. Brent cite wildly varying accounts of Stalin's last hours as evidence that -- at the least -- Stalin's Politburo colleagues denied him medical help in the first hours of his illness, when it might have been effective.

Khrushchev and others recalled long after Stalin's death that they had dined with him until the early hours of March 1. His and most other reports state that Stalin was later found sprawled unconscious on the floor, a copy of Pravda nearby.

Yet no doctors were summoned to the dacha until the morning of March 2. Why remains a mystery: one guard later said that Beria had called shortly after Stalin was found, ordering them to say nothing about his illness. Khrushchev wrote that Stalin had been drunk at the dinner and that his dinner companions, told of his illness, presumed that he had fallen out of bed -- until it became clear things were more serious.

More telling, however, is the official medical account of Stalin's death, given to the Communist Party Central Committee in June 1953 and buried in files for almost the next 50 years until unearthed by Mr. Naumov and Mr. Brent. It maintained that Stalin had become ill in the early hours of March 2, a full day after he actually suffered a stroke.

The effect of the altered official report is to imply that doctors were summoned quickly after Stalin was found, rather than after a delay.

The authors state that a cerebral hemorrhage is still the most straightforward explanation for Stalin's death, and that poisoning remains for now a matter of speculation. But Western physicians who examined the Soviet doctors' official account of Stalin's last days said similar physical effects could have been produced by a 5-to-10-day dose of warfarin, which had been patented in 1950 and was being aggressively marketed worldwide at the time.

Why Stalin might have been killed is a less difficult question. Politburo members lived in fear of Stalin; beyond that, the book cites a previously secret report as evidence that Stalin was preparing to add a new dimension to the alleged American conspiracy known as the Doctors' Plot.

That report -- an interrogation of a supposed American agent named Ivan I. Varfolomeyev, in 1951 -- indicated that the Kremlin was preparing to accuse the United States of a plot to destroy much of Moscow with a new nuclear weapon, then to launch an invasion of Soviet territory along the Chinese border.

Mr. Varfolomeyev's fantastic plot was known in Soviet documents as ''the plan of the internal blow.'' Stalin, the book states, had assigned the Varfolomeyev case highest priority, and was preparing to proceed with a public trial despite his underlings' fears that the charges were so unbelievable that they would make the Kremlin a global laughingstock.

Mr. Naumov said in an interview today that that plan, combined with other Soviet military preparations in the Russian Far East at the time, strongly suggest that Stalin was preparing for a war along the United States' Pacific Coast. What remains unclear, he said, is whether he planned a first strike or whether the mushrooming conspiracy unfolding in Moscow was to serve as a provocation that would lead both sides to a flash point.

''I am told that the only case when the two sides were on the verge of war was the Cuban crisis,'' in 1962, he said. ''But I think this was the first case. And this first time that we were on the verge of war was even more dangerous,'' because the devastation of nuclear weapons was not yet an article of faith.

Mr. Brent said he believes that fear of a nuclear holocaust could have led Beria and perhaps others at that final dinner to assent to Stalin's death.

''No question -- they were afraid,'' he said. ''But they knew that the direction Stalin was going in was one of fiercer and fiercer conflict with the U.S. This is what Khrushchev saw, and it is what Beria saw. And it scared them to death.''

The authors say that Stalin knew of his comrades' fears, citing as proof remarks at a December 1952 meeting of top Communist leaders in which Stalin began laying out the scope of the Doctors' Plot and the American threat to Soviet power.

''Here, look at you -- blind men, kittens,'' the minutes record Stalin as saying. ''You don't see the enemy. What will you do without me?''

Correction: March 8, 2003

An article on Wednesday about the death of Stalin and the possibility that he was poisoned by Politburo members to avert a looming war with the United States misstated the title and author of a memoir that included such a theory. It was by Vyacheslav M. Molotov, not by Nikita S. Khrushchev, and published in 1992 as ''Molotov Remembers.''