The Conversation

January 30, 2022

‘We have a chance to show the truth’: Inside Chernobyl's 'death zone' 30 years later

Ukraine and Russia share a great deal in the way of history and culture – indeed for long periods in the past, the neighboring countries were part of larger empires encompassing both territories.

But that history – especially during the Soviet period from 1922 to 1991, in which Ukraine was absorbed into the communist bloc – has also bred resentment. Opinions of the merits of the Soviet Union and its leaders diverge, with Ukrainians far less likely to view the period favorably than Russians.

Nonetheless, President Vladimir Putin continues to claim Soviet foundations for what he sees as “historical Russia” – an entity that includes Ukraine.

As scholars of that history, we believe that an examination of Soviet-era policies in Ukraine can offer a useful lens for understanding why so many Ukrainians harbor deep resentment toward Russia.

RAWSTORY+

Revisiting 'The Lost Boys of Ukraine': How the war abroad attracted American white supremacists

Stalin’s engineered famine

Throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries, Ukraine was known as the breadbasket of Europe and later of the Soviet Union. Its rich soil and ample fields made it an ideal place to grow the grain that helped feed the entire continent.

After Ukraine was absorbed into the Soviet Union beginning in 1922, its agriculture was subject to collectivization policies, in which private land was taken over by the Soviets to be worked communally. Anything produced on those lands would be redistributed across the union.

In 1932 and 1933, a famine devastated the Soviet Union as a result of aggressive collectivization coupled with poor harvests.

A deliberate famine?

Daily Express/Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Millions starved to death across the Soviet Union, but Ukraine felt the brunt of this horror. Research estimates that some 3 million to 4 million Ukrainians died of the famine, around 13% of the population, though the true figure is impossible to establish because of Soviet efforts to hide the famine and its toll.

Scholars note that many of the political decisions of the Soviet regime under Joseph Stalin – such as preventing Ukrainian farmers from traveling in search of food, and severely punishing anyone who took produce from collective farms – made the famine much worse for Ukrainians. These policies were specific to Ukrainians within Ukraine, as well as Ukrainians who lived in other parts of the Soviet Union.

Some historians claim that Stalin’s moves were done to quash a Ukrainian independence movement and were specifically targeted at ethnic Ukrainians. As such, some scholars call the famine a genocide. In Ukrainian, the event is known as “Holodomor,” which means “death by hunger.”

Recognition of the full extent of the Holodomor and implicating Soviet leadership for the deaths remains an important issue in Ukraine to this day, with the country’s leaders long fighting for global recognition of the Holodomor and its impact on modern Ukraine.

Countries such as the United States and Canada have made official declarations calling it a genocide.

But this is not the case in much of the rest of the world.

Just as the the Soviet government of the day denied that there were any decisions that explicitly deprived Ukraine of food – noting that the famine affected the entire country – so too do present-day Russian leaders refuse to acknowledge culpability.

Russia’s refusal to admit that the famine disproportionately affected Ukrainians has been taken by many in Ukraine as an attempt to downplay Ukrainian history and national identity.

Soviet annexation of Western Ukraine

This attempt to suppress Ukrainian national identity continued during and after World War II. In the early years of the Soviet Union, the Ukrainian national movement was concentrated in the western parts of modern-day Ukraine, part of Poland until the Nazi invasion in 1939.

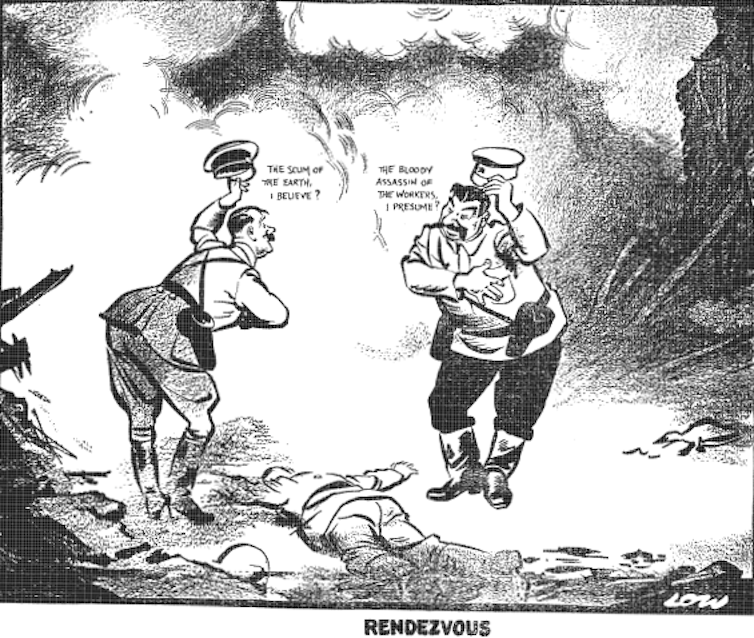

Before Gemany’s invasion, the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany entered into a secret agreement, under the guise of the Molotov-Ribbentrop nonaggression pact, which outlined German and Soviet spheres of influence over parts of central and east Europe.

David Low’s famed cartoon depicting Stalin and Hitler’s pact over Poland.

David Low/British Cartoon Archive at the University of Kent

After Germany invaded Poland, the Red Army moved into the eastern portion of the country under the pretense of stabilizing the failing nation. In reality, the Soviet Union was taking advantage of the provisions laid out in the secret protocol. The Polish territories that now make up western Ukraine were also incorporated into Soviet Ukraine and Belarus, subsuming them into the larger Russian cultural world.

At the end of the war, the territories remained part of the Soviet Union.

Stalin set about suppressing Ukrainian culture in these newly annexed lands in favor of a greater Russian culture. For example, the Soviets repressed any Ukrainian intellectuals who promoted the Ukrainian language and culture through censorship and imprisonment.

This suppression also included liquidating the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church, a self-governing church that has allegiance to the pope and was one of the most prominent cultural institutions promoting Ukrainian language and culture in these former Polish territories.

Its properties were transferred to the Russian Orthodox Church, and many of its priests and bishops were imprisoned or exiled. The destruction of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church is still a source of resentment for many Ukrainians. It stands, we believe as scholars, as a clear instance of the Soviets’ intentional efforts to destroy Ukrainian cultural institutions.

The legacy of Chernobyl in Ukraine

Just as disaster marked the early years of Ukraine as a Soviet republic, so did its final years.

In 1986 a nuclear reactor at the Soviet-run Chernobyl nuclear power in the north of Ukraine went into partial meltdown. It remains the worst peacetime nuclear catastrophe the world has seen.

It required the evacuation of nearly 200,000 people in the areas surrounding the power plant. And to this day, approximately 1,000 square miles of Ukraine are part of the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone, where radioactive fallout remains high and access is restricted.

Soviet lies to cover up the extent of the disaster – and missteps that would have limited the fallout – only compounded the problem. Emergency personnel were not given proper equipment or training to deal with the nuclear material.

It resulted in a heavy death toll and a higher than normal incidence of radiation-induced disease and complications such as cancer and birth defects among both former residents of the region and the workers sent in to deal with the disaster.

Other Soviet republics and European countries faced the fallout from Chernobyl, but it was the authorities in Ukraine who were tasked with organizing evacuations to Kyiv while Moscow attempted to cover up the scope of the disaster.

Meanwhile, independent Ukraine has been left to attend to the thousands of citizens who have chronic illnesses and disabilities as a result of the accident.

An abandoned fun fair, two kilometers from the Chernobyl power station.

Martin Godwin/Getty Images

The legacy of Chernobyl looms large in Ukraine’s recent past and continues to define many people’s memory of living in the Soviet era.

Memories of a painful past

This painful history of life under Soviet rule forms the backdrop to resentment in Ukraine today toward Russia. To many Ukrainians, these are not merely stories from textbooks, but central parts of people’s lives – many Ukrainians are still living with the health and environmental consequences of Chernobyl, for instance.

As Russia amasses troops at Ukraine’s borders, and the threat of an invasion increases, many in Ukraine may be reminded of past attempts by its neighbor to crush Ukrainian independence.

Emily Channell-Justice, Director of the Temerty Contemporary Ukraine Program, Harvard University and Jacob Lassin, Postdoctoral Research Scholar in Russian and East European Studies, Arizona State University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

SEE

Book Review: Marxism and the Philosophy of Science

Nikolai Vavilov in the years of Stalin's ‘Revolution from Above’ (1929–1932)

AbstractThis paper examines new evidence from Russian archives to argue that Soviet geneticist and plant breeder, Nikolai I. Vavilov's fate was sealed during the ‘Cultural Revolution’ (‘Revolution from Above’) (1929–1932). This was several years before Trofim D. Lysenko, the Soviet agronomist and widely portrayed archenemy and destroyer of Vavilov, became a major force in Soviet science. During the ‘Cultural Revolution’ the Soviet leadership wanted to subordinate science and research to the task of socialist reconstruction. Vavilov, who was head of the Institute of Plant Breeding (VIR) and the All-Union Academy of Agricultural Sciences (VASKhNIL), came under attack from the younger generation of researchers who were keen to transform biology into a proletarian science. The new evidence shows that it was during this period that Vavilov lost his independence to determine research strategies and manage personnel within his own institute. These changes meant that Lysenko, who had won Stalin's support, was able to gain influence and eventually exert authority over Vavilov. Based on the new evidence, Vavilov's arrest in 1940 after he criticized Lysenko's conception of Non-Mendelian genetics was just the final challenge to his authority. He had already experienced years of harassment that began before Lysenko gained a position of influence. Vavilov died in prison in 1943.

Politics of Perseverance: Ukrainian Memories of “Them” and the “Other” in Holodomor Survivor Testimony,

1986-1988

Johnathon K. Vsetecka,

.Unpublished Master of Arts thesis,

University of Northern Colorado, May 2014.

ABSTRACT

This thesis examines the famine of 1932-33 in Ukraine, now known as the Holodomor, from a survivor’s point of view. The Commission on the Ukraine Famine, beginning work in 1986, conducted an investigation of the famine and collected testimony from Holodomor survivors in the United States. This large collection of survivor testimonies sat quietly for many years, even though the Holodomor is now a recognized field of study in history, among other disciplines. A great deal of scholarship focuses on the political, genocidal, and ideological aspects of the famine, but few works explore the roles of everyday Ukrainian people. This thesis utilizes the testimonies to examine how everyday survivors construct memories based on their famine experiences. Survivors often share memories of themselves, but they also elaborate on the roles of others, which included Soviets, German villagers, and even other Ukrainians. These testimonies transcend the common victim and genocide narratives, showing that not all Ukrainians suffered equally. In fact, some survivors note that the famine did not disrupt their everyday lives at all. Collectively, these testimonies present a more complex narrative of everyday events in Ukraine and elucidate on the ways that survivors remember, interpret, and construct memories related to the Holodomor.

Johnathon K. Vsetecka,

.Unpublished Master of Arts thesis,

University of Northern Colorado, May 2014.

ABSTRACT

This thesis examines the famine of 1932-33 in Ukraine, now known as the Holodomor, from a survivor’s point of view. The Commission on the Ukraine Famine, beginning work in 1986, conducted an investigation of the famine and collected testimony from Holodomor survivors in the United States. This large collection of survivor testimonies sat quietly for many years, even though the Holodomor is now a recognized field of study in history, among other disciplines. A great deal of scholarship focuses on the political, genocidal, and ideological aspects of the famine, but few works explore the roles of everyday Ukrainian people. This thesis utilizes the testimonies to examine how everyday survivors construct memories based on their famine experiences. Survivors often share memories of themselves, but they also elaborate on the roles of others, which included Soviets, German villagers, and even other Ukrainians. These testimonies transcend the common victim and genocide narratives, showing that not all Ukrainians suffered equally. In fact, some survivors note that the famine did not disrupt their everyday lives at all. Collectively, these testimonies present a more complex narrative of everyday events in Ukraine and elucidate on the ways that survivors remember, interpret, and construct memories related to the Holodomor.

No comments:

Post a Comment