Unions are in a death spiral, and the numbers show they could nearly vanish within our lifetime. That’s not alarmism. It’s arithmetic.

Private sector union density has collapsed from about one-third of the workforce in the 1950s1 to just 5.9 percent in 2024.2 In the last twenty years, we’ve lost a quarter of private sector union density. Unions have failed to organize and win first contracts at a rate that can keep up with the growth of new jobs in the economy. As a result, union density has declined by about 0.1 percent a year over the past two decades. If nothing changes, we could fall to a mere 3.0 percent in the next thirty years, even as unions continue to win most National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) elections they file.

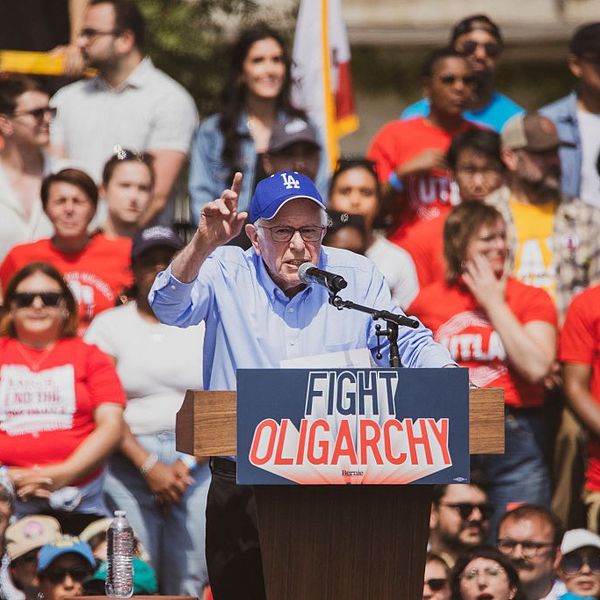

As union density has collapsed, wealth inequality has soared to levels not seen since the Great Depression, creating fertile ground for authoritarianism, right-wing nationalism, and racist scapegoating. Reversing this crisis requires nothing less than a mass, multiracial working-class movement to reclaim democracy—at the ballot box and in the workplace.

Fortunately, despite the hostile legal and political environment for unions, conditions are in many ways ripe for organizing. According to Gallup, 70 percent of Americans approve of unions and a large majority of Americans have sided with unions in their recent strikes.3 The Economic Policy Institute (EPI) estimates that sixty million workers, about half of non-union workers, would join a union today if they could.4 The working class has been ravaged by inflation, declining standards of living and even dropping life expectancy, and many workers are fed up and looking to fight back.

In many ways, unionization is a function of employer opposition and organizing capacity. A simple exercise in quantitative reasoning can give us a sense of how these variables interact, and of just how many workers the labor movement must organize to have a chance of pulling out of its downward spiral. The math is bleak, but not hopeless. What it reveals is both the scale of the crisis and the opportunity that exists if unions are willing to organize at a radically larger scale, put more workers in motion, and dramatically increase our organizing capacity.

More Wins, Fewer Workers

The Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) estimates a 5.9 percent rate of private sector union density. Assuming that the rate of job growth in the economy is 0.4 percent annually,5 and that this number compounds over time, then we can calculate the net number of workers that need to be organized and achieve first contracts to maintain a union density of 5.9 percent. However, winning union recognition is not enough. Since the goal of organizing is achieving a first contract, we should also take this into account when calculating a truer rate of union density. Importantly, first contract negotiations also provide employers with a second opportunity to break the union. As a result, supporting workers through the process of winning an initial agreement often requires significant organizing capacity (i.e. union resources and support that are then not utilized on further organizing campaigns).6 Including first contracts in our calculations goes a step further than the BLS data, but we can still use those numbers as a baseline for our purposes.

Unions are in a death spiral, and the numbers show they could nearly vanish within our lifetime. That’s not alarmism. It’s arithmetic.

Unfortunately, there is no reliable data on unions’ success rate at negotiating first agreements. Assuming, probably too generously, that 60 percent of workers who win recognition are successful in ratifying a first contract, then we divide the net number of workers needed to maintain density by first contract success rate to get the gross number of workers who successfully achieve recognition. Additionally, let’s assume it takes workers an average of 465 days to win and ratify that contract.7 This means that successfully building union density is often a multi-year effort. This significantly contributes to the challenge of achieving the organizing scales necessary to maintain, much less grow, union density. Assuming first contracts take, on average, about 465 days, about 150,000 gross workers must win union recognition by mid-2027 if we expect about 90,000 of them to be under ratified agreements by the end of 2028 and thereby hold 5.9 percent density.

Based on this very simple thought experiment, it becomes clear that given the length of time it takes to organize workplaces and win first agreements, unions must frontload the number of organizing campaigns in the pipeline if they hope to achieve a desired outcome later.8

Assuming all else remains the same, if the number of workers who achieve a first contract drops or the average time it takes to achieve a first contract expands, then the number of workers who successfully win recognition must increase and must increase even earlier if we are to hit the target of maintaining 5.9 percent density. For example, if the success rate for achieving first contracts is 50 percent, then the gross number of workers who need to achieve recognition by mid-2027 jumps to about 180,000 workers. If the first contract success rate drops to 40 percent, which may very well be the real-world approximation, then that number rises to 225,000 workers. Employer-induced failure to achieve first contracts is a density killer.

If 150,000 workers (or more) need to win recognition by mid-2027 to maintain current density by end of 2028, then let’s assume that around 100,000 workers need to win their union in 2026 and the remaining 50,000 need to win their union in the first half of 2027.

So how are we currently measuring up? The best place to start is by looking at how we did in 2024, which was widely lauded as a breakthrough year for union organizing. That year saw a total of 1,637 union elections. This was a substantial increase of 24 percent from 2023, but still far short of the 2,500 annual elections common just two decades earlier. It is also not even close to the more than 7,000 annual elections that were standard throughout the 1970s.

But the labor movement didn’t just run more union elections in 2024, we also won far more of them. According to union researcher Eric Dirnbach, private sector unions have enjoyed rising NLRB election win rates over the past two decades, going from winning little more than half of all elections in the 1990s to a win rate of 72 percent in 2022, 76 percent in 2023, and a historic all-time-high win rate of 77 percent in 2024. Dirnbach calculates that roughly 94,000 workers won NLRB elections in 2024, the highest number since 2001. The true total, including voluntary recognitions, is higher, though no official national count exists.9

While these numbers have been celebrated in many corners of the labor movement, a large dose of sobriety is in order. In what was considered a banner year for private sector organizing the labor movement barely surpassed the minimum number of gross workers that need to win recognition to simply maintain our current, abysmally low level of private sector union density. We will only sustain our current 5.9 percent density if we can continue to replicate the best organizing year in decades and if the rate for winning first contracts does not further decelerate, both of which are highly unlikely under the Trump administration. Even in the unlikely scenario that we can maintain the organizing successes of the past few years, this is still not enough to dramatically reverse our current course. Based on these numbers, it is highly likely that without greater urgency to organize union density will continue to drop.

Labor’s Hypothetical Event Horizon

At less than 6 percent private sector union density, the labor movement suffers from serious political, cultural, and institutional weaknesses. Unions are largely incapable of enforcing existing labor law, which employers violate with impunity, much less win new protections and rights such as the Employee Free Choice Act or the PRO Act. As labor shrinks, it becomes an increasingly insignificant political constituency in many areas of the country.

Unions could become too small to win big gains for current members, too weak to organize new workers at scale, too invisible to the public to matter. Beyond this threshold, there may be no climbing back.

The result is a vicious cycle. As union density shrinks, emboldened employers amass more profits from which to fund anti-union politicians, lobby for anti-worker legislation, finance more anti-union astro-turf organizations, and run even more ferocious union-busting campaigns in the workplace while unions are in an ever-weakening position to fight back. The results are evident. Fewer workers are covered by collective bargaining agreements, and even higher levels of profits are being siphoned off by wealthy corporate executives and shareholders.

Given this reality, we can, for the sake of this thought experiment, treat 3 percent private sector union density as a hypothetical event horizon for organized labor. This is the threshold beyond which unions become so small they lose the political, cultural, and institutional mass to successfully reverse their own decline.10

If private-sector density slips to around 3 percent, then the terrain begins to look like South Carolina everywhere: fewer than one in thirty-three workers is union, most never meet a union member on the job, and the movement’s cultural and political presence fades. At that level, the dues base and volunteer core are too small to sustain large-scale organizing, strike funds, or serious legislative offensives. To be clear, there would still be unions, and collective worker struggles will not end. So long as those struggles exist, there is hope. But in an environment where labor lacks institutional resources and visibility, the structural and legal headwinds will likely become too overwhelming to reestablish unions as a major force in political and economic life.

On average, BLS-reported union density has declined by 0.1 percent a year over the past two decades. Assuming this trend continues, we are on track to reach the event horizon in about thirty years. If the trend accelerates, or the event horizon is closer than we think, labor could descend into a negative feedback loop even sooner. Unions could become too small to win big gains for current members, too weak to organize new workers at scale, too invisible to the public to matter. Beyond this threshold, there may be no climbing back. Not in a generation. Maybe not ever. Our choices in the coming years will determine whether labor has a future, and whether we become the last generations to remember what it meant for the working class to have a fighting chance.

In short: we must organize or die. So, what would it look like to organize at scale and what would it take to make it happen?

It is imperative that labor takes these numbers seriously and begins a wholesale reassessment of the direction we are heading in and how to change it. In short: we must organize or die. So, what would it look like to organize at scale and what would it take to make it happen?

The Organizing Equation

In a truly free society, the number of workers who want a union and to bargain collectively would simply approximate the number of workers who do. One of the first steps to any worker hoping to unionize their workplace is knowing how to. Unfortunately, the vast majority of the 115.5 million non-union private sector workers out there have little to no idea what the NLRB is, what their rights are, or the extreme hostility they will face from their employer once they start talking to their coworkers about why unionizing makes sense. Sixty million workers may want a union, but nowhere near that number are active in organizing campaigns. Putting workers in motion is a pivotal first step.

Even if hundreds of thousands of workers decide to organize, their chances depend on whether unions have built enough infrastructure to match employer resistance.

There are several ways that workers might win recognition, including through a voluntary recognition agreement, private election agreement, recognition strike or labor board election. In some instances, the more power that a union has in a particular industry or in relation to a particular employer, the less workers who wish to join that union will have to rely on the NLRB. For example, this can happen through “bargaining to organize,” whereby unions secure neutrality or card check agreements in their already existing collective bargaining agreements with employers. This is one example of how higher union density can create a virtuous cycle of growth and power. Similarly, given low union density and the weakness of labor law, there might be conditions under which the only realistic way that workers at a given employer might ever win recognition is through a strike. Unfortunately, the BLS only tracks NLRB elections, so researchers do not have accurate information on the number of union recognition victories that happen through non-NLRB processes. That said, NLRB elections are still by far the most common method for workers to achieve union recognition from an employer.

Organizing success isn’t random. Whether workers win a union and a first contract depends on three simple things:

- How many workers want a union and are ready to act,

- How much resistance employers put up, and

- How much organizing capacity unions can bring to support workers.

An “organizing equation” can help us understand how these forces combine to affect the level of union density:

In plain language, the number of new union members joining the labor movement is equal to the number who want a union, multiplied by the fraction that begins organizing, multiplied by the fraction that achieves recognition, multiplied by the fraction that successfully win a first contract. In short, this equation treats the change in union density as the result of worker activation, union recognition, and first contract victory. Each stage is a potential breaking point. Millions of workers say they would join a union if they could, but only a fraction ever try to organize. Of those that try, some win recognition, and only a fraction still ever wins a contract.

Two powerful forces determine how far workers get along this chain. The first is employer opposition, which can range from low to moderate to extreme—offering sudden pay raises or perks to blunt union support, captive-audience meetings, threats of closure, discipline and firings, mobilization of the local business community and state political leaders, and delay tactics that drag the election out for months, to name just a few. The second is organizing capacity, the number and quality of organizers, staff, and peer leaders unions can deploy to help workers. Organizing capacity is the counterforce to employer opposition. More organizers, better training, and stronger systems help workers withstand and overcome fierce boss fights. When both forces are high, they partly cancel each other out; when opposition is extreme and capacity is low, employers crush union organizing.

Does the labor movement have the courage and tenacity to begin running many thousands of union elections every year, even if that means losing hundreds or thousands of elections in the process?

The organizing equation doesn’t predict what will happen in any single workplace. It’s a population-level model—a way to understand, in broad terms, how many of the roughly sixty million workers who want a union could win one under different sets of conditions. It captures a truth every organizer already knows: worker desire alone isn’t enough. The balance between employer power and union capacity determines whether organizing energy translates into actual unions.

Running the Thought Experiment

To show how this works, let’s assume just 1 percent of the sixty million workers who say they want a union, 600,000 people, decide to organize. The number of workers who successfully win union recognition and negotiate a first contract would vary dramatically depending on how hostile employers are and how much capacity unions have. Let’s assume further that a combination of high employer opposition and low organizing capacity yields a 20 percent success rate; moderate opposition and typical capacity yields a 50 percent success rate; and low opposition and high capacity yields an 80 percent success rate.

This thought experiment drives home some key truths about organizing. Even with the same number of workers trying to organize, the terrain determines the outcome. In a scenario defined by high employer opposition with little support, only one in five workers, or 120,000 out of 600,000, succeeds in winning their union and a first contract. Raising organizing capacity to a typical level and reducing employer opposition to a moderate level more than doubles the number of workers who win, to 300,000. In the best conditions, strong union support and manageable employer resistance, 480,000 workers win their union and a contract.

The lesson is simple: activation is necessary but not sufficient. Even if hundreds of thousands of workers decide to organize, their chances depend on whether unions have built enough infrastructure to match employer resistance. If we want to meet the moment, we must build that capacity at a scale labor hasn’t attempted in generations.

As labor unions have shrunk and employer hostility has increased over time, the number of organizing campaigns has significantly dropped. Today, most union drives don’t go to an election unless there is very high confidence that they will win. As mentioned previously, this has had the paradoxical effect of increasing union win rates over the past few years, while the number of workers filing for union elections has significantly dropped.11 Half a century ago, unions routinely ran more than 7,000 union elections a year in an attempt to represent four to five times the numbers of workers we are trying to organize today. In the 1980s, that number began to drop precipitously and hasn’t recovered.12 It’s been more than two decades since unions ran enough elections in one year to try and represent more than 200,000 workers (at a time when that represented a much larger share of the total private sector workforce). The last time we ran enough elections to try and represent 300,000 or more workers was 1981.

We must stop confusing caution with prudence. The future of labor depends on our willingness to be bold.

Previously, we assumed that 90,000 private sector workers needed to successfully win union recognition and a first contract by the end of 2028 to keep up with an economy with a job growth of 0.4 percent. If we want to go beyond just sustaining current density to building real power by growing, then that will only be achievable if labor starts trying to organize at a mass scale that we haven’t seen in decades.

Running thousands of more union elections is necessary, but not sufficient. The labor movement cannot overcome employer opposition or scale fast enough unless we dramatically increase our organizing capacity. If we hope to not just maintain density, but grow, we will need to train thousands of new organizers and deploy current staff strategically by designing organizing models that distribute rather than concentrate expertise. Without boosting our organizing capacity, even aggressive pushes to run organizing drives at far more workplaces will remain too few, too slow, or be too ineffective to reverse labor’s decline.

Scale or Fail

There are many assumptions in this thought experiment, and a lot of the numbers presented here can be challenged: a 0.4 percent compounding job growth in the economy, 3 percent density being the hypothetical event horizon for labor, a 60 percent baseline win rate for first contracts, how the impact of organizing capacity or employer opposition on organizing campaigns is conceptualized. But what the thought experiments above, for all their oversimplification, demonstrate is that unions will continue eroding their density and power over the next few decades if drastic action is not taken.

This should lead to some profound existential questions for the labor movement as a whole and for union leaders in particular:

- Do many union leaders truly understand how dire labor’s situation is?

- Do the organizing strategies currently underway come even close to the scale and ambition necessary to avoid labor’s event horizon?

- Are unions dynamic and open enough to running campaigns in ways that expand organizing expertise among workers rather than concentrating them among staff?

- Are unions willing to pour the resources necessary to train the thousands of organizers (both staff and rank-and-file) in rigorous organizing methods and put them to work on coordinated strategic campaigns that scale up our ability to win?

- What would it look like for organized labor to set a goal of trying to organize 600,000 workers, just 1 percent of the sixty million workers who say they want a union, a year?

- Does the labor movement have the courage and tenacity to begin running many thousands of union elections every year, even if that means losing hundreds or thousands of elections in the process?

- How can unions speed up the time it takes to win a first contract? Would it be worth prioritizing scale over depth by settling for much more limited first contracts with much shorter durations?

- How can the labor movement organize at scale despite the politically manufactured funding and operational crises at the NLRB?

The labor movement is dying, but it doesn’t have to. If we take risks, scale organizing and bargaining to match the moment, and treat each campaign as an opportunity to train and grow more organizers and bargainers, then we can reverse the vicious cycle we are in. This will inevitably require mass training, rigorous learning-through-doing, and organizational risk taking.

We cannot be afraid to lose union elections. In fact, we cannot be afraid to publicly lose on a larger scale. So long as unions are experimenting, learning, and using campaigns to develop new generations of worker leaders and organizers, the money spent on campaigns is not wasted, even when the outcome is disappointing. It is far better to fight and lose than to not fight at all. In fact, the insistence on only running union elections if we are highly confident that we will win could contribute to the slow eventual death of the labor movement.

We must stop confusing caution with prudence. The future of labor depends on our willingness to be bold. We don’t need perfection. We need more workers in struggle. The only way we can win is if we fight.

Notes

1. Gerald Mayer, “Union Membership Trends in the United States,” Congressional Research Service, The Library of Congress, 2004, available at https://ecommons.cornell.edu/items/d975928d-32bb-4625-9284-46efaa49563c.

2. Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Union Members Summary,” January 28, 2025, available at https://www.bls.gov/news.release/union2.nr0.htm. BLS union density data is not exact.

3. See Gallup’s historic polling on unions at https://news.gallup.com/poll/12751/labor-unions.aspx

4. Margaret Poydock, Celine McNicholas, Jennifer Sherer, and Heidi Shierholz, “16 Million Workers Were Unionized in 2024: Millions More Want to join Unions but Couldn’t,” Economic Policy Institute, January 29, 2025, available at https://files.epi.org/uploads/295318.pdf.

5. For this analysis, I assume an annual private-sector job growth rate of 0.4%, which is consistent with the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ (BLS) latest long-term employment projections for the 2023-2033 decade. Using the BLS figure provides a conservative baseline for modeling union density scenarios; if job growth is higher, the organizing requirements to maintain density would also be higher. U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Employment Projections—2023-2033 Summary,” September 4, 2024, available at https://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/ecopro.pdf.

6. Celine McNicholas, Margaret Poydock, and John Schmitt, “Workers Are Winning Union Elections, but It Can Take Years to Get Their First Contract,” Economic Policy Institute, May 1, 2023, available at https://www.epi.org/publication/union-first-contract-fact-sheet/.

7. In 2021, Bloomberg Law published an analysis of hundreds of union drives from 2005 to 2022 that estimated that the average length of time it takes for workers to win a first contract is 465 days. See Robert Combs, “Analysis: How Long Does It Take Unions to Reach a First Contract?” Bloomberg Law, June 1, 2021, available at https://news.bloomberglaw.com/bloomberg-law-analysis/analysis-how-long-does-it-take-unions-to-reach-first-contracts.

8. This simplified thought experiment assumes that unionized workplaces aren’t being offshored, shutting down, are experiencing layoffs, or are being outsourced, which would further deplete union density.

9. Eric Dirnbach, “U.S. Election Wins Surge in Fiscal Year 2024,” October 17, 2024, available at https://ericdirnbach.medium.com/u-s-union-election-wins-surge-in-fiscal-year-2024-cbcc3fd63c92.

10. I chose this number because it is about half of where we are today. Given how hard it is for unions to achieve success today, it’s simply unfathomable for me to see how unions can gain enough legitimacy, visibility and disruptive capacity to reverse our fates if private sector density declines by half from its already low rate.

11. For example, Eric Blanc has argued that “As recently as 1976-1980, unions ran about five times as many NLRB drives yearly as they do today, but their win rate was only about 48 percent. In contrast, as the total number of drives have plummeted in recent decades, labor’s win rate has steadily crept upwards, hovering at around 70 percent in recent years . . . Unions started avoiding many of the hardest battles and there were fewer overall attempts to organize. But those drives that were attempted tended to win more frequently.” Eric Blanc, “To Win Big, Labor Has to Lose More: Unionizing at Scale Requires a Higher Percentage of Losses,” May 20, 2024, available at https://www.laborpolitics.com/p/to-win-big-labor-has-to-lose-more.

12. For more background on the consistently high levels of union organizing drives from the 1950s through the 70s followed by the steep drop off starting in the 80s, see Lane Windham, Knocking on Labor’s Door: Union Organizing in the 1970s and the Roots of a New Economic Divide (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2017).