Firestorms and flaming tornadoes: how bushfires create their own ferocious weather systems

A firestorm on Mirror Plateau Yellowstone Park, 1988.

Jim Peaco/US National Park Service

Author

Rachel Badlan

November, 2019

As the east coast bushfire crisis unfolds, New South Wales Premier Gladys Berejiklian and Rural Fire Service operational officer Brett Taylor have each warned residents bushfires can create their own weather systems.

This is not just a figure of speech or a general warning about the unpredictability of intense fires. Bushfires genuinely can create their own weather systems: a phenomenon known variously as firestorms, pyroclouds or, in meteorology-speak, pyrocumulonimbus.

Read more: Firestorms: the bushfire/thunderstorm hybrids we urgently need to understand

The occurrence of firestorms is increasing in Australia; there have been more than 50 in the period 2001-18. During a six-week period earlier this year, 18 confirmed pyrocumulonimbus formed, mainly over the Victorian High Country.

A pyrocumulonimbus cloud generated by a bushfire in Licola,Victoria, on March 2, 2019. Elliot Leventhal, Author provided

Its not clear whether the current bushfires will spawn any firestorms. But with the frequency of extreme fires set to increase due to hotter and drier conditions, it’s worth taking a closer look at how firestorms happen, and what effects they produce.

What is a firestorm?

The term “firestorm” is a contraction of “fire thunderstorm”. In simple terms, they are thunderstorms generated by the heat from a bushfire.

In stark contrast to typical bushfires, which are relatively easy to predict and are driven by the prevailing wind, firestorms tend to form above unusually large and intense fires.

If a fire encompasses a large enough area (called “deep flaming”), the upward movement of hot air can cause the fire to interact with the atmosphere above it, potentially forming a pyrocloud. This consists of smoke and ash in the smoke plume, and water vapour in the cloud above.

If the conditions are not too severe, the fire may produce a cloud called a pyrocumulus, which is simply a cloud that forms over the fire. These are typically benign and do not affect conditions on the ground.

But if the fire is particularly large or intense, or if the atmosphere above it is unstable, this process can give birth to a pyrocumulonimbus – and that is an entirely more malevolent beast.

What effects do firestorms produce?

A pyrocumulonibus cloud is much like a normal thunderstorm that forms on a hot summer’s day. The crucial difference here is that this upward movement is caused by the heat from the fire, rather than simply heat radiating from the ground.

Conventional thunderclouds and pyrocumulonimbus share similar characteristics. Both form an anvil-shaped cloud that extends high into the troposphere (the lower 10-15km of the atmosphere) and may even reach into the stratosphere beyond.

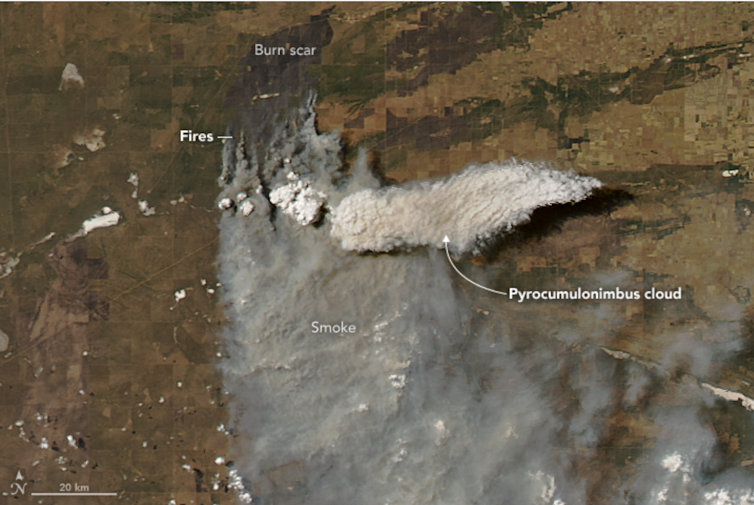

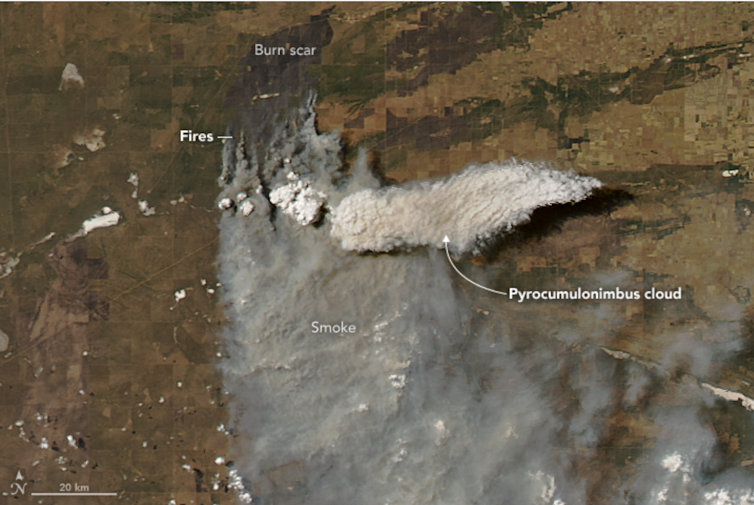

NASA image of pyrocumulonimbus formation in Argentina, January 2018. NASA

The weather underneath these clouds can be fierce. As the cloud forms, the circulating air creates strong winds with dangerous, erratic “downbursts” – vertical blasts of air that hit the ground and scatter in all directions.

In the case of a pyrocumulonimbus, these downbursts have the added effect of bringing dry air down to the surface beneath the fire. The swirling winds can also carry embers over huge distances. Ember attack has been identified as the main cause of property loss in bushfires, and the unpredictable downbursts make it impossible to determine which direction the wind will blow across the ground. The wind direction may suddenly change, catching people off guard.

Firestorms also produce dry lightning, potentially sparking new fires, which may then merge or coalesce into a larger flaming zone.

In rare cases, a firestorm can even morph into a “fire tornado”. This is formed from the rotating winds in the convective column of a pyrocumulonimbus. They are attached to the firestorm and can therefore lift off the ground.

Read more: Turn and burn: the strange world of fire tornadoes

This happened during the infamous January 2003 Canberra bushfires, when a pyrotornado tore a path near Mount Arawang in the suburb of Kambah.

A fire tornado in Kambah, Canberra, 2003 (contains strong language).

Understandably, firestorms are the most dangerous and unpredictable manifestations of a bushfire, and are impossible to suppress or control. As such, it is vital to evacuate these areas early, to avoid sending fire personnel into extremely dangerous areas.

The challenge is to identify the triggers that cause fires to develop into firestorms. Our research at UNSW, in collaboration with fire agencies, has made considerable progress in identifying these factors. They include “eruptive fire behaviour”, where instead of a steady rate of fire spread, once a fire interacts with a slope, the plume may attach to the ground and rapidly accelerate up the hill.

Another process, called “vorticity-driven lateral spread”, has also been recognised as a good indicator of potential fire blow-up. This occurs when a fire spreads laterally along a ridge line instead of following the direction of the wind.

Although further refinement is still needed, this kind of knowledge could greatly improve decision-making processes on when and where to deploy on-ground fire crews, and when to evacuate before the situation turns deadly.

Drought and climate change were the kindling, and now the east coast is ablaze

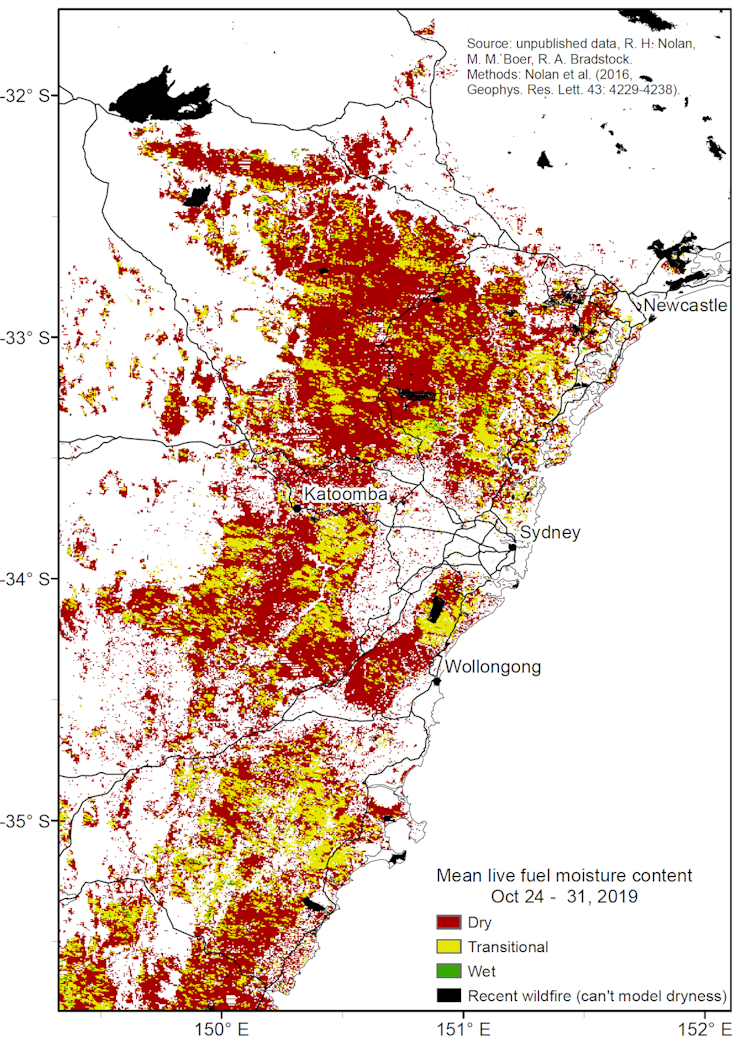

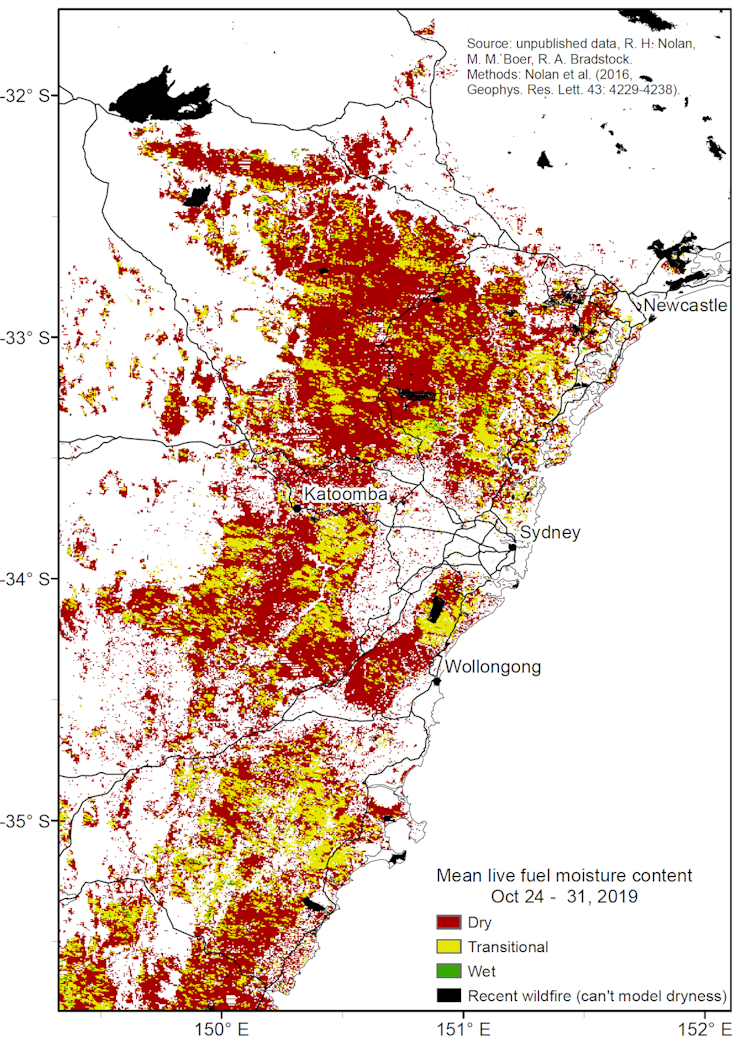

Live fuel moisture content in late October 2019. The ‘dry’ and ‘transitional’ moisture categories correspond to conditions associated with over 95% of historical area burned by bushfire. Estimated from MODIS satellite imagery for the Sydney basin Bioregion.

Live fuel moisture content in late October 2019. The ‘dry’ and ‘transitional’ moisture categories correspond to conditions associated with over 95% of historical area burned by bushfire. Estimated from MODIS satellite imagery for the Sydney basin Bioregion.

The NSW north coast and tablelands, along with much of the southern coastal regions of Queensland are famous for their diverse range of eucalypt forest, heathlands and rainforests, which flourish in the warm temperate to subtropical climate.

Read more: Climate change is bringing a new world of bushfires

Thus, the North Coast and northern ranges of NSW as well as much of southern and central Queensland have been primed for major fires. A continuous swathe of critically dry fuels across these diverse landscapes existed well before last week, as shown by damaging fires in September and October.

High temperatures and wind speeds, low humidity, and a wave of new ignitions on top of pre-existing fires has created an unprecedented situation of multiple large, intense fires stretching from the coast to the tablelands and parts of the interior.

More people in harm’s way

Many parts of the NSW north coast, southern Queensland and adjacent hinterlands have seen population growth around major towns and cities, as people look for pleasant coastal and rural homes away from the capital cities.

The extraordinary number and ferocity of these fires, plus the increased exposure of people and property, have contributed to the tragic results of the past few days.

Read more: How a bushfire can destroy a home

Communities flanked by forests along the coast and ranges are highly vulnerable because of the way fires spread under the influence of strong westerly winds. Coastal communities wedged between highly flammable forests and heathlands and the sea, are particularly at risk.

As a full picture of the extent and location of losses and damage becomes available, we will see the extent to which planning, building regulations, and fire preparation has mitigated losses and damage.

A firefighter defends a property in Torrington, near Glen Innes,

Sunday, November 10, 2019. There are more than 80 fires

burning around the state, with about half of those uncontained.

AAP Image/Dan Peled

These unprecedented fires are an indication that a much-feared future under climate change may have arrived earlier than predicted. The week ahead will present high-stakes new challenges.

The most heavily populated region of the nation is now at critically dry levels of fuel moisture, below those at the time of the disastrous Christmas fires of 2001 and 2013. Climate change has been predicted to strongly increase the chance of large fires across this region. The conditions for Tuesday are a real and more extreme manifestation of these longstanding predictions.

Read more: Where to take refuge in your home during a bushfire

Whatever the successes and failures in this crisis, it is likely that we will have to rethink the way we plan and prepare for wildfires in a hotter, drier and more flammable world.

---30---

Its not clear whether the current bushfires will spawn any firestorms. But with the frequency of extreme fires set to increase due to hotter and drier conditions, it’s worth taking a closer look at how firestorms happen, and what effects they produce.

What is a firestorm?

The term “firestorm” is a contraction of “fire thunderstorm”. In simple terms, they are thunderstorms generated by the heat from a bushfire.

In stark contrast to typical bushfires, which are relatively easy to predict and are driven by the prevailing wind, firestorms tend to form above unusually large and intense fires.

If a fire encompasses a large enough area (called “deep flaming”), the upward movement of hot air can cause the fire to interact with the atmosphere above it, potentially forming a pyrocloud. This consists of smoke and ash in the smoke plume, and water vapour in the cloud above.

If the conditions are not too severe, the fire may produce a cloud called a pyrocumulus, which is simply a cloud that forms over the fire. These are typically benign and do not affect conditions on the ground.

But if the fire is particularly large or intense, or if the atmosphere above it is unstable, this process can give birth to a pyrocumulonimbus – and that is an entirely more malevolent beast.

What effects do firestorms produce?

A pyrocumulonibus cloud is much like a normal thunderstorm that forms on a hot summer’s day. The crucial difference here is that this upward movement is caused by the heat from the fire, rather than simply heat radiating from the ground.

Conventional thunderclouds and pyrocumulonimbus share similar characteristics. Both form an anvil-shaped cloud that extends high into the troposphere (the lower 10-15km of the atmosphere) and may even reach into the stratosphere beyond.

NASA image of pyrocumulonimbus formation in Argentina, January 2018. NASA

The weather underneath these clouds can be fierce. As the cloud forms, the circulating air creates strong winds with dangerous, erratic “downbursts” – vertical blasts of air that hit the ground and scatter in all directions.

In the case of a pyrocumulonimbus, these downbursts have the added effect of bringing dry air down to the surface beneath the fire. The swirling winds can also carry embers over huge distances. Ember attack has been identified as the main cause of property loss in bushfires, and the unpredictable downbursts make it impossible to determine which direction the wind will blow across the ground. The wind direction may suddenly change, catching people off guard.

Firestorms also produce dry lightning, potentially sparking new fires, which may then merge or coalesce into a larger flaming zone.

In rare cases, a firestorm can even morph into a “fire tornado”. This is formed from the rotating winds in the convective column of a pyrocumulonimbus. They are attached to the firestorm and can therefore lift off the ground.

Read more: Turn and burn: the strange world of fire tornadoes

This happened during the infamous January 2003 Canberra bushfires, when a pyrotornado tore a path near Mount Arawang in the suburb of Kambah.

A fire tornado in Kambah, Canberra, 2003 (contains strong language).

Understandably, firestorms are the most dangerous and unpredictable manifestations of a bushfire, and are impossible to suppress or control. As such, it is vital to evacuate these areas early, to avoid sending fire personnel into extremely dangerous areas.

The challenge is to identify the triggers that cause fires to develop into firestorms. Our research at UNSW, in collaboration with fire agencies, has made considerable progress in identifying these factors. They include “eruptive fire behaviour”, where instead of a steady rate of fire spread, once a fire interacts with a slope, the plume may attach to the ground and rapidly accelerate up the hill.

Another process, called “vorticity-driven lateral spread”, has also been recognised as a good indicator of potential fire blow-up. This occurs when a fire spreads laterally along a ridge line instead of following the direction of the wind.

Although further refinement is still needed, this kind of knowledge could greatly improve decision-making processes on when and where to deploy on-ground fire crews, and when to evacuate before the situation turns deadly.

Drought and climate change were the kindling, and now the east coast is ablaze

November 11, 2019

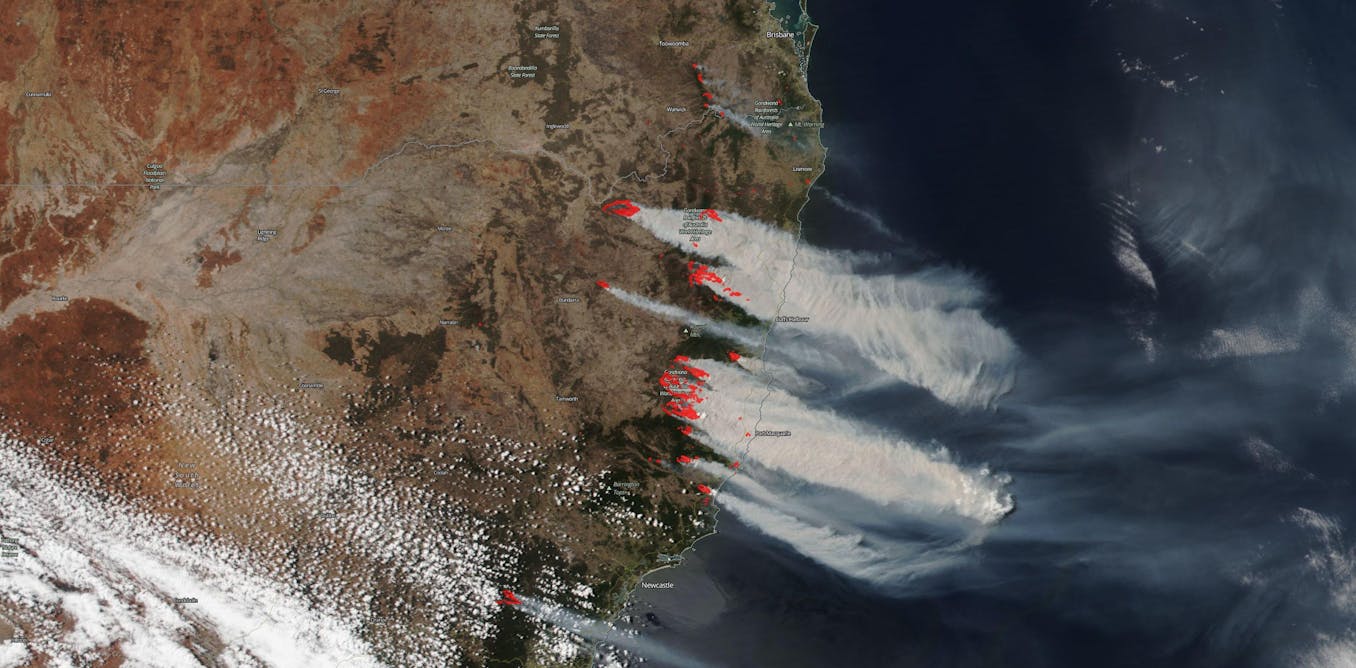

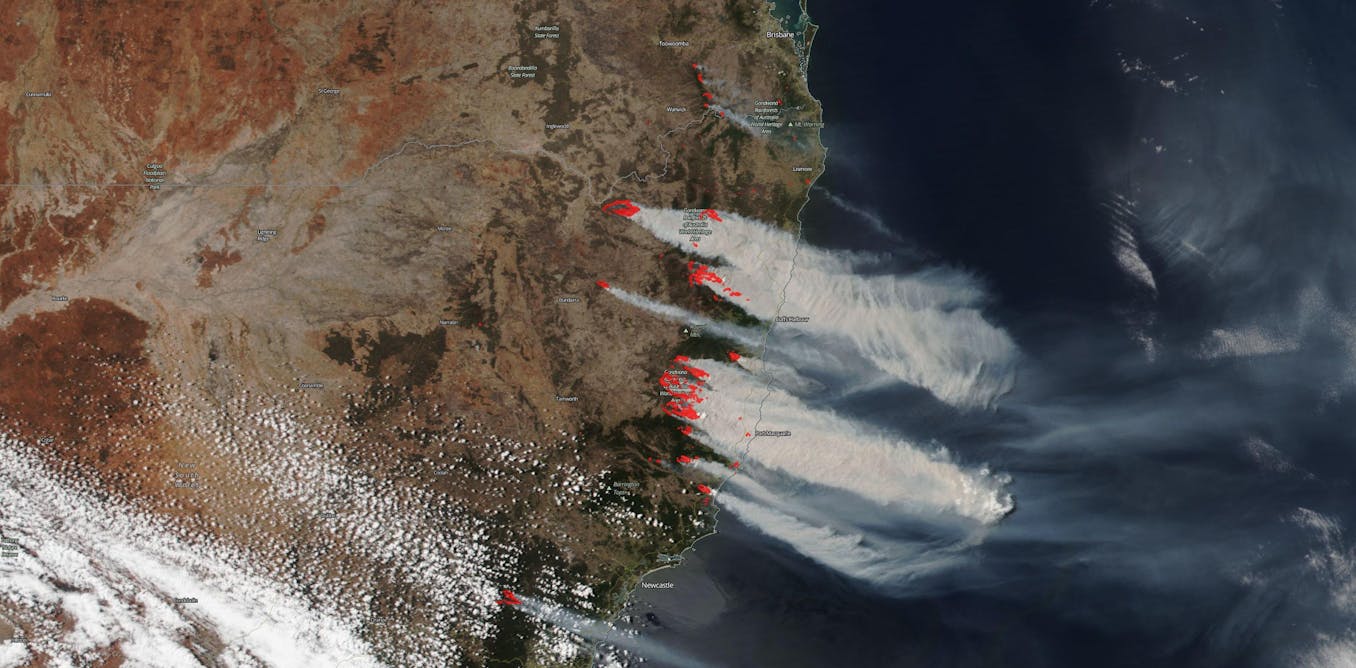

Last week saw an unprecedented outbreak of large, intense fires stretching from the mid-north coast of New South Wales into central Queensland.

The most tragic losses are concentrated in northern NSW, where 970,000 hectares have been burned, three people have died, and at least 150 homes have been destroyed.

A catastrophic fire warning for Tuesday has been issued for the Greater Sydney, Greater Hunter, Shoalhaven and Illawarra areas. It is the first time Sydney has received a catastrophic rating since the rating system was developed in 2009.

No relief is in sight from this extremely hot, dry and windy weather, and the extraordinary magnitude of these fires is likely to increase in the coming week. Alarmingly, as Australians increasingly seek a sea-change or tree-change, more people are living in the path of these destructive fires.

Read more: It's only October, so what's with all these bushfires? New research explains it

Unprecedented state of emergency

Large fires have happened before in northern NSW and southern Queensland during spring and early summer (for example in 1994, 1997, 2000, 2002, and 2018 in northern NSW). But this latest extraordinary situation raises many questions.

It is as if many of the major fires in the past are now being rerun concurrently. What is unprecedented is the size and number of fires rather than the seasonal timing.

The potential for large, intense fires is determined by four fundamental ingredients: a continuous expanse of fuel; extensive and continuous dryness of that fuel; weather conditions conducive to the rapid spread of fire; and ignitions, either human or lightning. These act as a set of switches, in series: all must be “on” for major fires to occur.

Last week saw an unprecedented outbreak of large, intense fires stretching from the mid-north coast of New South Wales into central Queensland.

The most tragic losses are concentrated in northern NSW, where 970,000 hectares have been burned, three people have died, and at least 150 homes have been destroyed.

A catastrophic fire warning for Tuesday has been issued for the Greater Sydney, Greater Hunter, Shoalhaven and Illawarra areas. It is the first time Sydney has received a catastrophic rating since the rating system was developed in 2009.

No relief is in sight from this extremely hot, dry and windy weather, and the extraordinary magnitude of these fires is likely to increase in the coming week. Alarmingly, as Australians increasingly seek a sea-change or tree-change, more people are living in the path of these destructive fires.

Read more: It's only October, so what's with all these bushfires? New research explains it

Unprecedented state of emergency

Large fires have happened before in northern NSW and southern Queensland during spring and early summer (for example in 1994, 1997, 2000, 2002, and 2018 in northern NSW). But this latest extraordinary situation raises many questions.

It is as if many of the major fires in the past are now being rerun concurrently. What is unprecedented is the size and number of fires rather than the seasonal timing.

The potential for large, intense fires is determined by four fundamental ingredients: a continuous expanse of fuel; extensive and continuous dryness of that fuel; weather conditions conducive to the rapid spread of fire; and ignitions, either human or lightning. These act as a set of switches, in series: all must be “on” for major fires to occur.

Live fuel moisture content in late October 2019. The ‘dry’ and ‘transitional’ moisture categories correspond to conditions associated with over 95% of historical area burned by bushfire. Estimated from MODIS satellite imagery for the Sydney basin Bioregion.

Live fuel moisture content in late October 2019. The ‘dry’ and ‘transitional’ moisture categories correspond to conditions associated with over 95% of historical area burned by bushfire. Estimated from MODIS satellite imagery for the Sydney basin Bioregion.The NSW north coast and tablelands, along with much of the southern coastal regions of Queensland are famous for their diverse range of eucalypt forest, heathlands and rainforests, which flourish in the warm temperate to subtropical climate.

Read more: Climate change is bringing a new world of bushfires

These forests and shrublands can rapidly accumulate bushfire fuels such as leaf litter, twigs and grasses. The unprecedented drought across much of Australia has created exceptional dryness, including high-altitude areas and places like gullies, water courses, swamps and steep south-facing slopes that are normally too wet to burn.

These typically wet parts of the landscape have literally evaporated, allowing fire to spread unimpeded. The drought has been particularly acute in northern NSW where record low rainfall has led to widespread defoliation and tree death. It is no coincidence current fires correspond directly with hotspots of record low rainfall and above-average temperatures.

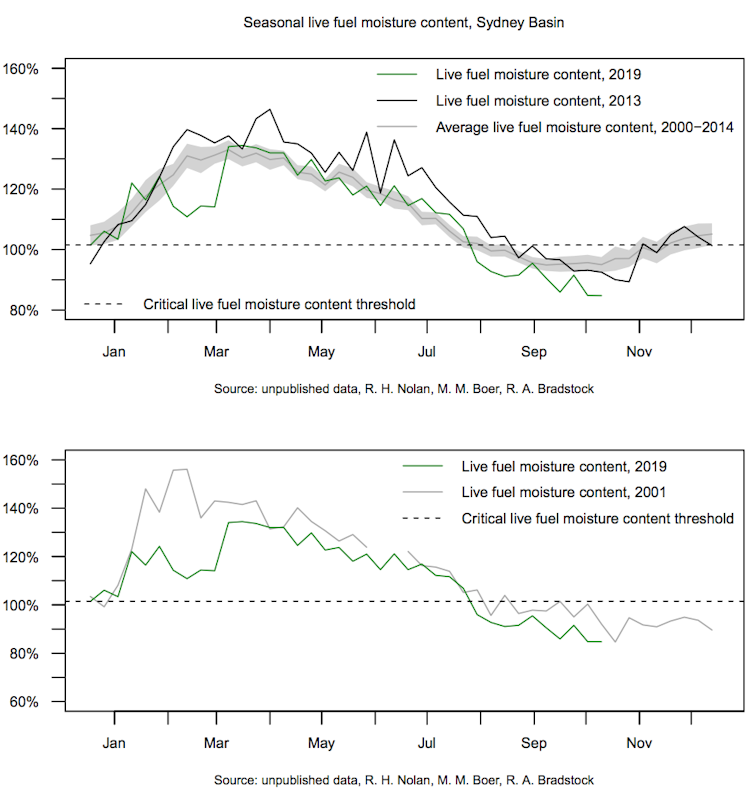

Annual trends in live fuel moisture. The horizontal line represents the threshold for the critical ‘dry’ fuel category, which corresponds to the historical occurrence of most major wildfires in the Bioregion. Estimated from MODIS imagery for the Sydney basin Bioregion

Thus, the North Coast and northern ranges of NSW as well as much of southern and central Queensland have been primed for major fires. A continuous swathe of critically dry fuels across these diverse landscapes existed well before last week, as shown by damaging fires in September and October.

High temperatures and wind speeds, low humidity, and a wave of new ignitions on top of pre-existing fires has created an unprecedented situation of multiple large, intense fires stretching from the coast to the tablelands and parts of the interior.

More people in harm’s way

Many parts of the NSW north coast, southern Queensland and adjacent hinterlands have seen population growth around major towns and cities, as people look for pleasant coastal and rural homes away from the capital cities.

The extraordinary number and ferocity of these fires, plus the increased exposure of people and property, have contributed to the tragic results of the past few days.

Read more: How a bushfire can destroy a home

Communities flanked by forests along the coast and ranges are highly vulnerable because of the way fires spread under the influence of strong westerly winds. Coastal communities wedged between highly flammable forests and heathlands and the sea, are particularly at risk.

As a full picture of the extent and location of losses and damage becomes available, we will see the extent to which planning, building regulations, and fire preparation has mitigated losses and damage.

A firefighter defends a property in Torrington, near Glen Innes,

Sunday, November 10, 2019. There are more than 80 fires

burning around the state, with about half of those uncontained.

AAP Image/Dan Peled

These unprecedented fires are an indication that a much-feared future under climate change may have arrived earlier than predicted. The week ahead will present high-stakes new challenges.

The most heavily populated region of the nation is now at critically dry levels of fuel moisture, below those at the time of the disastrous Christmas fires of 2001 and 2013. Climate change has been predicted to strongly increase the chance of large fires across this region. The conditions for Tuesday are a real and more extreme manifestation of these longstanding predictions.

Read more: Where to take refuge in your home during a bushfire

Whatever the successes and failures in this crisis, it is likely that we will have to rethink the way we plan and prepare for wildfires in a hotter, drier and more flammable world.

Professor, Centre for Environmental Risk Management of Bushfires, University of Wollongong

Professor, Centre for Environmental Risk Management of Bushfires, University of Wollongong Postdoctoral research fellow, Western Sydney University

Postdoctoral research fellow, Western Sydney University

---30---

SEE https://plawiuk.blogspot.com/search?q=COAL

SEE https://plawiuk.blogspot.com/search?q=AUSTRALIA

SEE https://plawiuk.blogspot.com/search?q=WILDFIRES

SEE https://plawiuk.blogspot.com/search?q=BUSHFIRES

SEE https://plawiuk.blogspot.com/search?q=CLIMATE+CHANGE

No comments:

Post a Comment