The Trojan asteroid 2020 XL5, which follows the same path around the sun as our planet, was revealed only after a decade of searching.

By Kenneth Chang

Feb. 2, 2022

Sign up for Science Times Get stories that capture the wonders of nature, the cosmos and the human body. Get it sent to your inbox.

Astronomers have discovered a captive asteroid shadowing Earth in its orbit.

The asteroid, known as 2020 XL5, is only the second of its type ever seen, shepherded by Earth’s gravity into an orbit that is locked in synchrony with our planet’s. It has not shared our orbit for long — a few centuries, probably. And it will not be there in the far future. Simulations indicate that 2020 XL5 will slip out of Earth’s grasp within 4,000 years and head into the wider solar system.

But its presence offers a tantalizing glimpse of what else might be out there in the local gravitational whirlpools. Some bits might date back to the beginning of the solar system — shades of the building blocks that coalesced into our planet.

“These objects are not as exotic as we think,” said Toni Santana-Ros, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Barcelona in Spain and an author of a paper describing the discovery, which was published on Tuesday in the journal Nature Communications. (A separate team of astronomers came to a similar conclusion in December.)

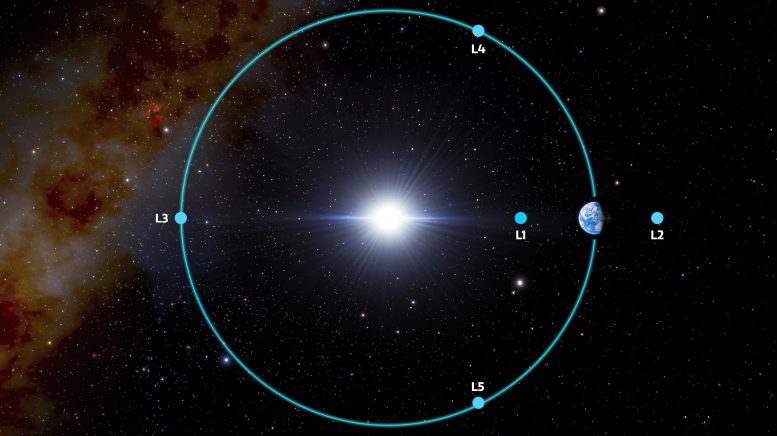

When two objects orbit each other, there are five points, known as Lagrange points, where the gravity of the two essentially balance, and a much smaller mass can sit there in equilibrium. Two of the five Lagrange points, known as L4 and L5, are stable: If a small body there is nudged slightly, it remains at that point. At the three unstable Lagrange points — L1 through L3 — a nudge will push the small body away for good.

(The unstable Lagrange points can still be very useful. The newly launched James Webb Space Telescope is about 900,000 miles away at the second Lagrange point, or L2, of the sun-Earth system. The instrument relies on thrusters to keep it from drifting away.)

Back in 1906, Max Wolf, a German astronomer who developed a photographic technique to discover asteroids, found an asteroid in the same orbit as Jupiter, always ahead of the planet by 60 degrees, or one-sixth of an orbit. Later observers found other asteroids in about the same place as well as asteroids that lagged Jupiter by the same margin.

These fit a prediction made more than a century earlier by mathematician Jose-Louis Lagrange. Astronomers started naming these objects after heroes of the Trojan War, and the bodies became known as the Trojan asteroids.

Many of Jupiter’s more than 11,000 Trojans do appear to be primordial remnants from the formation of the solar system. In October, NASA launched a probe named Lucy, after the fossilized skeleton of an early hominid ancestor, to visit several of them.

Similar asteroids appear to be trapped in the orbits of Venus, Mars, Uranus and Neptune. None have been found sharing Saturn’s orbit — the disruptive gravity of Jupiter is thought to be at fault — or Mercury’s, where any tiny Trojans would be all but impossible to find in the glare of the sun.

Earth also appeared to lack Trojan asteroids until astronomers found one in 2010 at the L4 Lagrange point, 60 degrees ahead of Earth. Subsequent searches came up empty until Pan-Starrs, an automated sky survey in Hawaii, turned up an intriguing object, 2020 XL5, that seemed like it might also be trapped around L4.

But the initial observations were insufficient to definitively pin down the object’s orbit. In 2021, an international team of astronomers including Dr. Santana-Ros made additional sightings of 2020 XL5 using three ground-based telescopes. The team was then able to search through images dating back to 2012 — where the asteroid indeed appeared, although no one had recognized it as one.

A decade of data was finally enough to firmly chart 2020 XL5’s elliptical orbit. “We were 100 percent sure this was an Earth Trojan,” Dr. Santana-Ros said.

Although 2020 XL5 is trapped in an orbit around a stable Lagrange point, it is not particularly close to L4. Its elliptical orbit, tilted nearly 14 degrees to the orbit of the planets, sweeps it closer to the sun than Venus and almost as far out as Mars.

Most Recent: Space

An Electrifying View of the Heart of the Milky Way

A new radio-wave image of the center of our galaxy reveals all the forms of frenzy that a hundred million or so stars can get up to. Jan. 31, 2022

Japanese Company Joins March Back to the Moon in 2022

Before the end of the year, ispace aims to place a lander with two small rovers on the lunar surface. It may find other visitors have also made the trip this year. Jan. 25, 2022

Bouncing Boulders Point to Quakes on Mars

A preponderance of boulder tracks on the red planet may be evidence of recent seismic activity. Jan. 22, 2022

This makes it vulnerable to gravitational buffeting from other planets, especially Venus.

The researchers ran computer simulations of the orbit of 2020 XL5, tweaking it 800 times. Sometimes the asteroid escaped from the Lagrange point within 3,500 years; sometimes it loitered 5,000 years or more. But the orbit appears unlikely to remain stable for much longer than that

From appearances, 2020 XL5 is a dark, carbon-rich body, perhaps an interloper from the main asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter. The researchers estimate its diameter at about three-quarters of a mile, much larger than the Earth Trojan discovered in 2010, which was estimated to be about a quarter-mile in diameter and is also located at the L4 Lagrange point.

Whereas the two known Earth Trojans appear to be transitory additions to our orbital neighborhood, other bodies that hover closer to the stable Lagrange points could remain in place indefinitely, raising the possibility that some of the primordial building blocks of Earth might still be found there.

“All the formation models gives you the idea that planets should have these families going around their L4 and L5 points from the beginning,” said Federica Spoto, an astronomer at the Center for Astrophysics in Cambridge, Mass., who was not involved with the research.

She added, “If we were able to find something like that, we might be able to understand what happened at the beginning, basically.”

Kenneth Chang has been at The Times since 2000, writing about physics, geology, chemistry, and the planets. Before becoming a science writer, he was a graduate student whose research involved the control of chaos. @kchangnyt

Better Understand Space and Astronomy

We can help you keep track of things going on in our solar system and all around the universe.

Never miss a rocket launch, astronaut landing or other events that are out of this world with The Times’s Space and Astronomy Calendar.

The solar system is filled with robotic explorers. Learn more about the spacecraft studying the secrets of the sun, moon and other worlds.

Keep track of the major meteor showers that light up night skies all year long.

Confused by black holes? You’re not alone. Let us unpack some of the universe’s most mysterious forces for you.

Existence of Earth Trojan Asteroid Confirmed – Could Become “Ideal Bases” for Advanced Exploration of the Solar System

Using the 4.1-meter SOAR (Southern Astrophysical Research) Telescope on Cerro Pachón in Chile, astronomers have confirmed that an asteroid discovered in 2020 by the Pan-STARRS1 survey, called 2020 XL5, is an Earth Trojan (an Earth companion following the same path around the Sun as Earth does) and revealed that it is much larger than the only other Earth Trojan known.

Data from NSF’s NOIRLab Show Earth Trojan Asteroid Is the Largest Found

The SOAR Telescope, part of NOIRLab’s Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory, has helped astronomers refine the size and orbit of the largest known Earth Trojan companion.

By scanning the sky very close to the horizon at sunrise, the SOAR Telescope in Chile, part of Cerro-Tololo Inter-American Observatory, a Program of NSF’s NOIRLab, has helped astronomers confirm the existence of only the second-known Earth Trojan asteroid and reveals that it is over a kilometer wide — about three times larger than the first.

Astronomers have confirmed the existence of the second known Earth Trojan asteroid and found that it is much bigger than the first. An Earth Trojan is an asteroid that follows the same path around the Sun as Earth does, either ahead of or behind Earth in its orbit. Called 2020 XL5 the asteroid was discovered by the Pan-STARRS1 survey telescope in 2020, but astronomers were not sure then whether it was an Earth Trojan. The SOAR Telescope operated by NOIRLab in Chile helped confirm that it is an Earth Trojan and found that it is over a kilometer across — almost three times bigger than the other Earth Trojan known.

Using the 4.1-meter SOAR (Southern Astrophysical Research) Telescope on Cerro Pachón in Chile, astronomers led by Toni Santana-Ros of the University of Alicante and the Institute of Cosmos Sciences of the University of Barcelona observed the recently discovered asteroid 2020 XL5 to constrain its orbit and size. Their results confirm that 2020 XL5 is an Earth Trojan — an asteroid companion to Earth that orbits the Sun along the same path as our planet does — and that it is the largest one yet found.

“Trojans are objects sharing an orbit with a planet, clustered around one of two special gravitationally balanced areas along the orbit of the planet known as Lagrange points,”[1] says Cesar Briceño of NSF’s NOIRLab, who is one of the authors of a paper published today in Nature Communications reporting the results, and who helped make the observations with the SOAR Telescope at Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory (CTIO), a Program of NSF’s NOIRLab, in March 2021.

Several planets in the Solar System are known to have Trojan asteroids, but 2020 XL5 is only the second known Trojan asteroid found near Earth.[2]

Lagrange points are places in space where the gravitational forces of two massive bodies, such as the Sun and a planet, balance out, making it easier for a low-mass object (such as a spacecraft or an asteroid) to orbit there. This diagram shows the five Lagrange points for the Earth-Sun system. (The size of Earth and the distances in the illustration are not to scale.) Credit:

NOIRLab/NSF/AURA/J. da Silva, Acknowledgment: M. Zamani (NSF’s NOIRLab)

Observations of 2020 XL5 were also made with the 4.3-meter Lowell Discovery Telescope at Lowell Observatory in Arizona and by the European Space Agency’s 1-meter Optical Ground Station in Tenerife in the Canary Islands.

Discovered on December 12, 2020, by the Pan-STARRS1 survey telescope in Hawai‘i, 2020 XL5 is much larger than the first Earth Trojan discovered, called 2010 TK7. The researchers found that 2020 XL5 is about 1.2 kilometers (0.73 miles) in diameter, about three times as wide as the first (2010 TK7 is estimated to be less than 400 meters or yards across).

When 2020 XL5 was discovered, its orbit around the Sun was not known well enough to say whether it was merely a near-Earth asteroid crossing our orbit, or whether it was a true Trojan. SOAR’s measurements were so accurate that Santana-Ros’s team was then able to go back and search for 2020 XL5 in archival images from 2012 to 2019 taken as part of the Dark Energy Survey using the Dark Energy Camera (DECam) on the Víctor M. Blanco 4-meter Telescope located at CTIO in Chile. With almost 10 years of data on hand, the team was able to vastly improve our understanding of the asteroid’s orbit.

This graphic shows where the Earth Trojan asteroid 2020 XL5 would appear in the sky from Cerro Pachón in Chile as the asteroid orbits the Earth-Sun Lagrange point 4 (L4). The arrows show the direction of its motion. The SOAR Telescope appears in the lower left. The asteroid’s apparent magnitude is around magnitude 22, beyond the reach of anything but the largest telescopes. Credit: NOIRLab/NSF/AURA/J. da Silva

Although other studies have supported the Trojan asteroid’s identification,[3] the new results make that determination far more robust and provide estimates of the size of 2020 XL5 and what type of asteroid it is.

“SOAR’s data allowed us to make a first photometric analysis of the object, revealing that 2020 XL5 is likely a C-type asteroid, with a size larger than one kilometer,” says Santana-Ros. A C-type asteroid is dark, contains a lot of carbon, and is the most common type of asteroid in the Solar System.

The findings also showed that 2020 XL5 will not remain a Trojan asteroid forever. It will remain stable in its position for at least another 4000 years, but eventually it will be gravitationally perturbed and escape to wander through space.

2020 XL5 and 2010 TK7 may not be alone — there could be many more Earth Trojans that have so far gone undetected as they appear close to the Sun in the sky. This means that searches for, and observations of, Earth Trojans must be performed close to sunrise or sunset, with the telescope pointing near the horizon, through the thickest part of the atmosphere, which results in poor seeing conditions. SOAR was able to point down to 16 degrees above the horizon, while many 4-meter (and larger) telescopes are not able to aim that low.[4].

“These were very challenging observations, requiring the telescope to track correctly at its lowest elevation limit, as the object was very low on the western horizon at dawn,” says Briceño.

Nevertheless, the prize of discovering Earth Trojans is worth the effort of finding them. Because they are made of primitive material dating back to the birth of the Solar System and could represent some of the building blocks that formed our planet, they are attractive targets for future space missions.

“If we are able to discover more Earth Trojans, and if some of them can have orbits with lower inclinations, they might become cheaper to reach than our Moon,” says Briceño. “So they might become ideal bases for an advanced exploration of the Solar System, or they could even be a source of resources.”

Notes

- Lagrange points are gravitationally balanced regions around two massive bodies, such as the Sun and a planet. The Earth-Sun system has five Lagrange points: L1 is between Earth and the Sun; L2 is on the opposite side of Earth from the Sun; L3 is on the opposite side of the Sun from Earth; and L4 and L5 are along Earth’s orbit, one 60 degrees ahead of our planet along its orbit and the other 60 degrees behind it. (The image in the middle of this article illustrates their positions.) Trojan asteroids are found at L4 and L5. The two Earth Trojans found so far are at L4.

- Jupiter has over 5000 known Trojan asteroids, and a NASA spacecraft called Lucy has recently launched on a mission to explore them. Venus, Mars, Uranus, and Neptune are also known to have Trojan asteroids.

- Man-To Hui (Macau University of Science and Technology) and collaborators published observations in the Astrophysical Journal Letters in December 2021 supporting the Trojan nature of 2020 XL5.

- These kinds of observations low in the sky are also the ones that will be most affected by the increasing number of satellite constellations.

More information

This research is presented in a paper titled “Orbital stability analysis and photometric characterization of the second Earth Trojan asteroid 2020 XL5” published on 1 February 2022 in Nature Communications.

Reference: “Orbital stability analysis and photometric characterization of the second Earth Trojan asteroid 2020 XL5” by T. Santana-Ros, M. Micheli, L. Faggioli, R. Cennamo, M. Devogèle, A. Alvarez-Candal, D. Oszkiewicz, O. Ramírez, P.-Y. Liu, P. G. Benavidez, A. Campo Bagatin, E. J. Christensen, R. J. Wainscoat, R. Weryk, L. Fraga, C. Briceño and L. Conversi, 1 February 2022, Nature Communications.

DOI: 10.1038/s41467-022-27988-4

The team is composed of T. Santana-Ros (Departamento de Fisica, Ingeniería de Sistemas y Teoría de la Señal, Universidad de Alicante; Institut de Ciències del Cosmos, Universitat de Barcelona), M. Micheli (ESA NEO Coordination Centre), L. Faggioli (ESA NEO Coordination Centre), R. Cennamo (ESA NEO Coordination Centre), M. Devogèle (Arecibo Observatory; University of Central Florida), A. Alvarez-Candal (Instituto de Astrofísica de Andalucía, CSIC; Instituto de Física Aplicada a las Ciencias y las Tecnologías, Universidad de Alicante; Observatório Nacional / MCTIC), D. Oszkiewicz (Faculty of Physics, Astronomical Observatory Institute), O. Ramírez (Solenix Deutschland), P.-Y. Liu (Instituto de Física Aplicada a las Ciencias y las Tecnologías, Universidad de Alicante), P.G. Benavidez (Departamento de Fisica, Ingeniería de Sistemas y Teoría de la Señal, Universidad de Alicante; Instituto de Física Aplicada a las Ciencias y las Tecnologías, Universidad de Alicante), A. Campo Bagatin (Departamento de Física, Ingeniería de Sistemas y Teoría de la Señal, Universidad de Alicante; Instituto de Física Aplicada a las Ciencias y las Tecnologías, Universidad de Alicante), E.J. Christensen (Lunar and Planetary Laboratory, University of Arizona,), R. J. Wainscoat (Institute for Astronomy, University of Hawaii), R. Weryk (Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of Western Ontario), L. Fraga (Laboratório Nacional de Astrofísica LNA/MCTI), C. Briceño (Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory/NSF’s NOIRLab), and L. Conversi (ESA NEO Coordination Centre; ESA ESRIN).

No comments:

Post a Comment