The International Monetary Fund: an ABC 2.0

HAPPY 80TH

Like the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) was created in 1944 at Bretton Woods. Its official purpose was to stabilize the international financial system by regulating the circulation of capital. What it has become is the main international institution whose task is to impose inhuman neoliberal policies all over the planet. It is clearly an anti-democratic entity at the service of the interests of the major powers and large private corporations. The conditional granting of credits to countries in difficulty is one of its principal means of exerting pressure. In 2024, 191 countries were members.

Undemocratic leadership

The IMF’s organization is similar to that of the World Bank: each country appoints a governor, usually its finance minister or the governor of its central bank. Together they form the Board of Governors, the IMF’s sovereign instance; meetings take place once a year in October. The Board of Governors makes the major decisions (such as admitting new countries and preparing the budget).

For the day-to-day operation of the IMF’s missions, it delegates its power to an executive board, which consists of 24 members. The following eight countries – the same as for the World Bank – are entitled to one board member each: the US, Japan, Germany, France, the UK, Saudi Arabia, China and Russia. The other 16 board members are appointed by groups of countries that may differ slightly from those at the World Bank.

The third managing body is the International Monetary and Financial Committee (IMFC), which includes the 24 governors of the countries sitting on the executive board. It meets twice a year (in spring and autumn) and advises the IMF on the functioning of the international monetary system.

The executive board elects a managing director for a five-year term. Acting as a counterpart to the unspoken rule in force at the World Bank, this post is held by a European. The Frenchman Michel Camdessus held this position from 1987 to 2000, before resigning after the economic crisis in South-East Asia. The IMF had helped creditors who had made risky investments and imposed economic measures that resulted in more than 20 million people losing their jobs, leading to strong popular protests and the destabilization of several governments. The Spaniard Rodrigo Rato took over in 2004 before resigning in 2007 to join the international department of Lazard Bank in London. [1] In 2017, Rato was sentenced to four years in prison by a Spanish court for embezzlement at Bankia Bank. Frenchman Dominique Strauss-Kahn, the socialist former finance minister, became managing director in 2007, before having to resign in 2011 after being charged with sexual assault by a hotel chambermaid. [2] In July 2011, Christine Lagarde, who had up until then been the French finance minister, stepped in. Lagarde was sued in the Crédit Lyonnais case, which cost French taxpayers a great deal of money. She left her position in 2019 to become president of the European Central Bank. A great deal could be said about the IMF under her leadership. After Lagarde’s departure, the Europeans and Washington again agreed on a European at the head of the institution. She is Kristalina Georgieva, a Bulgarian economist and former Chief Executive of the World Bank Group from January 2017 to September 2019, who had acted as President for three months. At the beginning of her mandate with the IMF, Kristalina Georgieva’s action at the head of the World Bank was questioned. She was accused of having influenced the authors of the Doing Business report to increase China’s ranking. An audit report drafted by the law firm WilmerHale at the request of the World Bank, criticizes in particular “pressure applied by CEO Georgieva and her advisor, Mr. Djankov, to make specific changes to China’s data points in an effort to increase its ranking at precisely the same time the country was expected to play a key role in the Bank’s capital increase campaign.” [3]

No matter, she was confirmed as IMF managing director and was reelected in 2024. [4]

In 2024, the IMF’s staff consisted of 3,100 senior executives from 162 countries, most of them based in Washington, DC. The IMF ‘number two’ (First Deputy Managing Director, FDMD) is always a representative of the US, which has paramount influence within the institution. During the Asian crisis in 1997–98, FDMD Stanley Fischer bypassed Michel Camdessus on several occasions. Anne Krueger played a very active part in the Argentine crisis of 2001–02. From 2006 to 2011, John Lipsky, former chief economist at J.P. Morgan, one of the main US business banks, played a leading role. As early as March 2010 he had warned that, as reported in a Reuters article, ‘developed countries with big budget deficits must start now to prepare public opinion for the belt-tightening that will be needed, starting next year’. [5] Twelve years later, we can only conclude that the neoliberal agenda has been enforced everywhere, with Greece, Ireland and Portugal having been monitored by the IMF since 2010. The IMF has also developed its damaging influence in many countries of the South. In 2018, it granted the biggest loan in its history to Mauricio Macri’s neoliberal regime in Argentina, a docile ally of the US. This resulted in a huge fiasco in 2019. Fortunately the measures imposed by the IMF on countries such as Ecuador and Haiti led to huge popular mobilizations in 2019 (in the case of Ecuador, the measures had to be abandoned under the pressure of the mass demonstrations). Later the IMF used the international debt crisis in countries of the south that started in 2022 to enforce a large number of austerity measures in approximately one hundred countries that asked for emergency loans. This resulted in major popular protests in Nigeria and Kenya in 2024. In the latter country the government had to abandon the most unpopular measures.

Operation on the private-enterprise model

Since 1969, the IMF has had its own accounting system that governs its financial activities with member countries, based on units known as Special Drawing Rights (SDR). This was devised at a time when the system established at Bretton Woods, based on fixed exchange rates, was faltering. Its aim was to remedy shortfall in reserve assets at the time, especially in gold and the US dollar. It was not able to prevent Bretton Woods from collapsing in the wake of President Nixon’s decision to terminate the free convertibility of the US dollar to gold in 1971. With a system of floating exchange rates, the SDR has mainly become just another reserve asset. Originally valued at 1 USD, it is now revalued daily from a basket of hard currencies (the US dollar, the yen, the euro, the pound sterling, and since 2016 the Chinese renminbi). [6] In 2023, the IMF board approved a steep increase in SDRs that mainly benefited to the riched countries.

Quite unlike any democratic institution, the IMF functions almost exactly like a business. Any country that becomes a member must pay an entry fee known as a ‘quota share’ and thus becomes a shareholder. The quota share is calculated according to the country’s economic and geopolitical importance. Twenty-five per cent of it must normally be paid in SDR or one of its component currencies (or in gold, until 1978) and the rest in the country’s local currency.

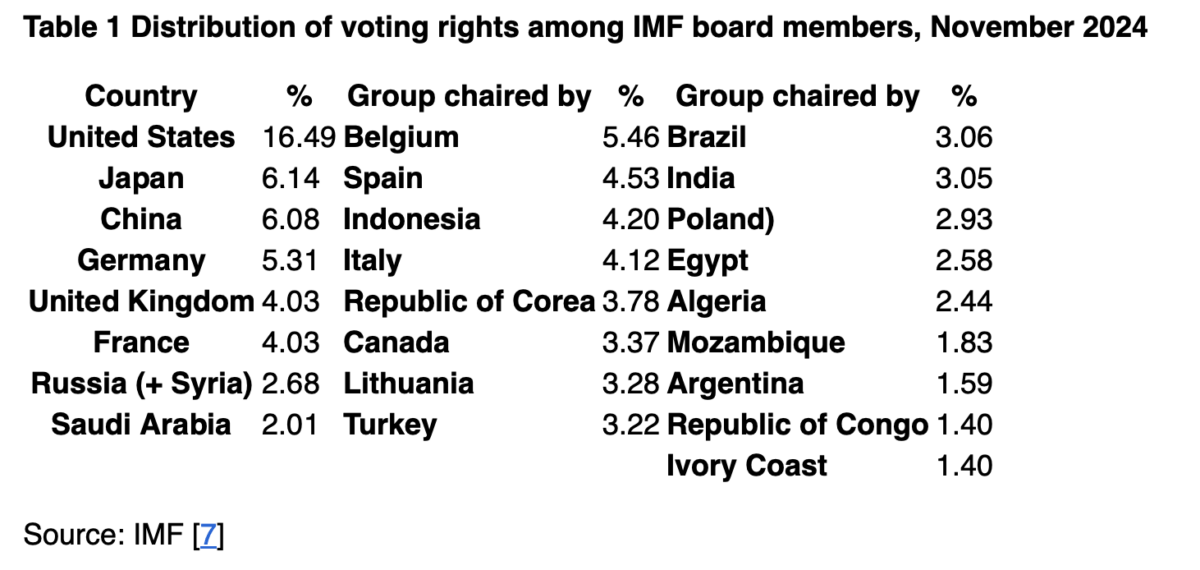

As with the World Bank, a country’s quota share determines the voting rights it has within the IMF, which corresponds to 250 votes plus one vote per tranche of 100,000 SDR of quota share. This is how the executive board of the IMF gives the United States its predominant position (with 16.49 per cent of voting rights). By way of comparison, in November 2024, Republic of the Congo chaired a group of 17 African countries representing 487 million individuals – 152 million more than the United States – yet had only 1,40 per cent of voting rights, or eleven times less than the United States.

In 2016, under pressure from emerging countries, a reform of the transfer of voting rights came into force, but it was in fact a masquerade.

It is clear that within such a system, countries of the North easily manage to muster a majority and effectively run the IMF.

Their actual power is disproportionate compared with that of countries of the South, whose voting rights are ludicrously low in comparison with the number of inhabitants.

In early November 2024, the IMF decided to create a 25th executive director’s position. It had been talked about for some fifteen years, and was to be awarded to sub-Saharan Africa. Is this good news for Africa? Will it benefit from greater consideration by the Fund’s governing bodies?

In fact we have to say straightaway that this is not good news: the countries of Sub-Saharan Africa belonged to two groups (except Ghana that was in a third group) that totalled 4.63% in voting power. Now they belong to three groups instead of two and have 4.61% of votes. So in terms of votes within the IMF board, the weight of Africa has not increased, and even slightly decreased.

Before this position was created, the group presided by Tanzania included 23 countries and had 3.02% of votes; the group presided by Congo Brazzaville included 23 countries and had 1.61% of votes. This meant a total of 4.63% of votes in the IMF.

Now the group presided by Mozambique includes 14 countries with 1.83% of votes, the group presided by Côte d’Ivoire includes 14 pays with 1.40% of votes and the group presided by Congo includes 17 countries with 1.40% of votes. This means a total of 4.61% of votes in the IMF.

The United States on their own have an executive director with 16.49% of votes in a context in which significant votes require 85% of votes. The US are thus the only country who alone has veto power.

France has 4.03% of votes, so hardly less than all Sub-Saharan African countries together.

Germany has 5.31% of votes, so more than those countries together.

It must also be said that two major countries of Sub-Saharan Africa had lost a significant part of their voting power with the previous reform in 2010, implemented from 2016. Indeed south Africa lost 21% of its votes and Nigeria 41% (see Patrick Bond, https://www.cadtm.org/The-BRICS-New-Development-Bank-Sub-Imperialism-Working-within-not-against ).

A Difference with the World Bank

Unlike the World Bank, the IMF uses states’ subscriptions to constitute its reserves for lending to countries with a temporary deficit. These loans are granted on condition of signing an agreement dictating the measures the country must enforce. The money is released in tranches, after verification that the measures demanded have effectively been applied.

As a general rule, a country in difficulty can borrow up to 100 per cent of its quota share from the IMF annually and up to 300 per cent in all, barring emergency procedures. The loan is short-term and the country is expected to repay the IMF as soon as its financial situation is back to normal.

In fact, the IMF levies interest surcharges on the loans it grants to countries that call on its services. The interest rate charged by the IMF when it applies a surcharge can be as high as 8%.

The worse people fare, the greater the IMF’s influence

The IMF is thus one of the largest holders of gold reserves, third in line after the United States and Germany, since countries used the precious metal to pay their subscription to the IMF. In addition, in 1970–71, South Africa – which the IMF saw no reason to rebuff despite its notorious violations of human rights under the apartheid regime – sold it huge quantities of gold.

In the early twenty-first century, when all its major clients had paid what they owed in advance or ceased to call on its resources, the IMF went through a delicate financial period and in April 2008, its executive board approved the sale of 403 tons of gold at a price of $11 billion, to replenish its coffers. Although those reserves are not used for IMF loans, they nevertheless give it the stability and stature it needs to retain the consideration of international financial actors.

After a significant decrease in outstanding credits from the IMF to member states, the international crisis which erupted in 2007–08 provided the ideal pretext for resuming the attack, multiplying loans, especially to European countries, using them as a justification for imposing draconian antisocial measures and harsh austerity on populations.

We can clearly see in the above table that the stock of loans granted by the IMF dwindled between 2003 and 2007 from over USD90 billion to only USD13.1 billion. With the 2008 financial crisis and its recessive effects on the world economy in 2009, the stock of IMF loans increased again and was over USD100 billion per year between 2011 and 2014. A decline followed between 2015 and 2017. A new increase started in 2018 with the huge loan to Mauricio Macri’s neoliberal government in Argentina, under Donald Trump’s presidency. IMF loans further increased with the CoViD-19 pandemic in 2020, the consequences of the invasion of Ukraine in 2022 and the rise of interest rates decided on by major Western central banks (the US Federal Reserve, the European Central Bank, the Bank of England). We note that in 2023, repayments to the IMF (USD37.8 billion) were well beyond new loans (USD 27.6 billion). In short, the worse people fare, the greater the IMF’s influence.

The IMF thus uses desperate situations to increase the influence of neoliberal capitalism. Contrary to what it sometimes claims, it never cancels any debt. When the IMF or the World Bank boast about cancelling debts, they actually take money from a special funds fed by member countries of the IMF or the World Bank. Conclusion: 1) countries that feed this fund count their contribution as official development assistance (ODA), which sometimes leads them to cut other ODA spending; 2) the IMF does not cancel debt, because when part of the debt of a country in difficulty is restructured, it is repaid thanks to the special fund provided by member countries.

The IMF, a Public Danger

The IMF’s purpose, as defined by Article I (ii) of its Articles of Agreement is ‘To facilitate the expansion and balanced growth of international trade, and to contribute thereby to the promotion and maintenance of high levels of employment and real income and to the development of the productive resources of all members as primary objectives of economic policy.’ [8]

In fact, the policies of the IMF are in contradiction with its statutes. The institution does not promote high levels of employment and income. Under the influence of the US Treasury and backed up by the other Northern countries, the IMF has taken it upon itself to become a major player in defining the economic and financial policies of its member countries. And to do so, it does not hesitate to go far beyond its mandate.

The IMF has thus facilitated the current complete freedom of capital movements throughout the world, one of the major causes of the financial crises that have so cruelly hit the countries of the South. Lifting all controls on capital movements favours speculation and is in contradiction with Section 3 of Article VI of the IMF statutes, which states, ‘Members may exercise such controls as are necessary to regulate international capital movements’. [9]

Surveillance, financial aid and technical assistance are the three fields in which the IMF intervenes. However, neither annual monitoring of member countries nor its experts’ recommendations have enabled the IMF to foresee and avoid the major crises that have occurred since 1994. The policies dictated by the IMF have in fact aggravated them.

‘The G7 governments, particularly the United States, use the IMF as a vehicle to achieve their political ends. […] Numerous studies of the effects of IMF lending have failed to find any significant link between IMF involvement and increases in wealth or income. IMF-assisted bailouts of creditors in recent crises have had especially harmful and harsh effects on developing countries. People who have worked hard to struggle out of poverty have seen their achievements destroyed, their wealth and savings lost, and their small businesses bankrupted. Workers lost their jobs, often without any safety-net to cushion the loss. Domestic and foreign owners of real assets suffered large losses, while foreign creditor banks were protected.’

– Report of the International Financial Institution Advisory Commission of the US Congress, or Meltzer Commission, 2000

Translated by Christine Pagnoulle and Vicki Briault.

Footnotes

[1] The Lazard Bank specializes in financial counselling and asset management, notably with governments that face financial problems. For instance, it advised the Greek government in 2015, and we know how successful that was. It also advises the predatory regime in Congo-Brazzaville.

[2] See Éric Toussaint and Damien Millet, ‘FMI : la fin de l’histoire?’ (‘IMF: the end of the story?’), CADTM, 20 May 2011 (in French only) <cadtm.org/FMI-la-fin-de-l-histoire?…> [accessed 01/11/2021].

[3] WilmerHale, “Investigation Findings and Report to the Board of Executive Directors”, 15 September 2021, https://thedocs.worldbank.org/en/doc/84a922cc9273b7b120d49ad3b9e9d3f9-0090012021/original/DB-Investigation-Findings-and-Report-to-the-Board-of-Executive-Directors-September-15-2021.pdf (accessed 9/12/2024).

[4] IMF, “Kristalina Georgieva, IMF managing director: bio”, https://www.imf.org/en/About/senior-officials/Bios/kristalina-georgieva (accessed 18/11/2024).

[5] Photo : Nikkul, CC, Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Urban_Poverty.jpg

[6] On 01/11/2021, 1 USD was valued at 0.708807 SDR; see <imf.org/external/np/fin/data/param_…> .

[7] IMF, ‘IMF executive directors and voting power’ <imf.org/external/np/sec/memdir/eds.aspx> [accessed 29/12/2021].

[8] IMF, Articles of Agreement (Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund, 2020), p. 2 <imf.org/external/pubs/ft/aa/pdf/aa.pdf> [accessed 2/11/2021].

[9] IMF, Articles of Agreement, p. 20.

No comments:

Post a Comment