(RNS) — The image of Our Lady of Guadalupe, whose feast day falls on Dec. 12, has emerged as a symbol among Latino activists and artists in the U.S. and Mexico of their support for Palestinians in Gaza.

An individual scales a building after hanging a banner depicting the Virgin of Guadalupe with a sign reading “My son is Palestinian” in Spanish, on a parking garage facing the Catholic Metropolitan Cathedral of Chihuahua, Mexico.

(Photo by Raúl F. Pérez Lira/Raíchali)

Alejandra Molina

December 11, 2024

LOS ANGELES (RNS) — In mid-October, the day before the one-year anniversary of Hamas’ attack on southern Israel, activists in Chihuahua, Mexico, strung a banner bearing a pro-Palestinian message from a parking garage to the Catholic Metropolitan Cathedral of Chihuahua.

In Spanish, the words “My son is Palestinian” were emblazoned in bold red letters below a depiction of the Virgin of Guadalupe, the brown-skinned virgin and patron saint of Mexico, wearing a black-and-white kaffiyeh and a cloak decorated with tiny watermelons, both symbols of Palestinian resistance.

To one of the persons who created the banner, who asked to remain anonymous, there was no better way to evoke reaction than by communicating through the Virgin of Guadalupe. “We wanted to reach people’s hearts. The Virgin is a figure of authority. It’s as if she’s saying, ‘My children, don’t be indifferent,’” said the activist.

As Israel’s war in Gaza continues, the image of Our Lady of Guadalupe, whose feast day falls on Dec. 12, has emerged as a symbol of Palestinian support among Latino activists and artists in the U.S. and Mexico. More than 44,000 Palestinians have been killed so far in the war that began after Hamas militants killed some 1,200 people and abducted around 250 others on Oct.7, 2023.

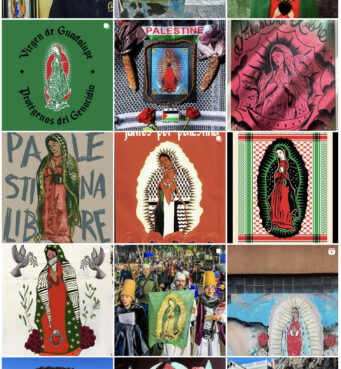

A variety of Palestinian-themed Virgin of Guadalupe artwork on the “Where’s Lupita?” Instagram. (Screen grab)

The art features traditional and interpretative images of the Virgin of Guadalupe fused with watermelons and kaffiyehs, symbols that represent Palestinian identity and resistance. Many of the illustrations are featured on the Instagram known as “Where’s Lupita?,” which tracks global Virgin Mary iconography.

Some illustrations appeared on Instagram as fundraising efforts for UNRWA USA, a nonprofit that raises funds and supports the work of the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees.

Gustavo Martinez Contreras, creator of Where’s Lupita?, said artists using Guadalupe’s image in support of Palestinians are continuing a tradition of Chicanos who harnessed the Virgin as a symbol “in defiance against the system.” To Martinez Contreras, these depictions symbolize Guadalupe as “caring for the marginalized.”

Daisy Vargas, a professor at the University of Arizona who specializes in Catholicism in the Americas, sees this artwork as “important interpretations for this particular political and cultural moment,” noting that artists are drawing parallels between the current violence in Gaza and the biblical narratives of Mary as the Palestinian mother of Jesus “who is experiencing the violence of empire in an occupied land.”

Vargas also sees a connection to the story of the apparition in Mexico. “These are symbols that are important within the context of people who have experienced a history of colonial and imperial violence and displacement from their own homelands,” Vargas said.

The feast of Our Lady of Guadalupe marks the Catholic Church teaching that the Virgin Mary appeared to St. Juan Diego, an Indigenous Mexican, on a Tepeyac hill in present-day Mexico City in 1531. The Virgin Mary took the form of a mixed-race woman who spoke Nahuatl, the language of the people that had been recently colonized by Spain, writes art history professor Judith Huacuja.

Daisy Vargas. (Photo courtesy of University of Arizona)

In the 19th century the Virgin was invoked during the Mexican independence movement, when images of the Virgin were emblazoned on banners protesting the Spanish occupation. Today, the Virgin has been used as a symbol of resistance against housing displacement and as a protector of migrants.

“Artists are using the symbol of the Virgin because it’s a powerful symbol of Latinidad,” said Vargas, using a Spanish word referring to Latin identity. “It’s a powerful symbol of Christianity. It’s a powerful symbol of maternal love. … It really asks people to consider what is happening in Gaza, and how it (connects) to their own identity and their own faith traditions.”

“Virgencita Palestine,” by Ernesto Yerena, an artist and printmaker in Los Angeles, juxtaposes the iconic image of the Virgin of Guadalupe against a kaffiyeh-patterned backdrop in red and green, the colors that appear on both the Mexican and Palestinian flags. Yerena sold the prints in January to raise money to fund and distribute “Free Palestine” posters at pro-Palestinian rallies.

“I would say a lot of people who identify as Latinos, Latinas, they would dig this image. They would feel it’s representative of the way we feel,” said Yerena.

Though he grew up Catholic, Yerena said he isn’t religious and he rebukes what he sees as a disparity between the Catholic Church’s wealth and charity work. The Virgin of Guadalupe, however, “has a warm place in my heart because of my grandmothers, my mom. They love the Virgen,” he said.

“I’ll always feel connected to it even though I don’t identify as Catholic,” said Yerena, who identifies as Chicano and Indigenous. Among his great-grandparents, he said, were Yaqui, and Indigenous Mexican people, and a Sephardic Jew.

Yerena learned about “oppressed peoples” solidarity movements with Palestine in his 20s, he said, and soon after began creating art in solidarity with Palestinian people, drawing inspiration from political posters of the Organization in Solidarity with the People of Africa, Asia, and Latin America. He said he has been called antisemitic for his work, which he finds ironic, given his family history. “I’m proud of my Jewish heritage,” he said.

A banner depicting the Virgin of Guadalupe with the words “My son is Palestinian” in Spanish hangs from a parking garage facing the Catholic Metropolitan Cathedral of Chihuahua, Mexico. (Photo by Raúl F. Pérez Lira/Raíchali)

Catholic Church leaders have been criticized for allowing a Nativity scene featuring a Christ child in a kaffiyah — since removed — in the Vatican’s Christmas display in St. Peter’s Square, and other antisemitism watchdog groups have objected to efforts to merge Palestinian and Christian imagery. (Martinez Contreras, founder of Where’s Lupita?, was fired from his job in 2021 for writing a misogynistic and antisemitic caption that he said was accidentally published by the newspaper he was working for.)

Lizett Carmona, an artist based in Chicago, created a Virgin of Guadalupe draped in a black and white kaffiyeh, with the words “juntos por palestina” (together for Palestine) displayed above the Virgin’s image. With her piece, she’s petitioning for protection of Palestinians.

“I wanted to show solidarity and find some interconnectedness … between me, someone of Mexican descent, and someone from Palestine,” said Carmona.

Her work touches on themes of migration and liberation and features images of police cars on fire and of children selling candy at the border.

RELATED: Chronicling Los Angeles’ iconic Virgin of Guadalupe street art

Carmona, an agnostic who considers Catholicism integral with her culture, thinks of Guadalupe as “the product of colonialism.” “But then I think a lot of our identity, we are byproducts of colonialism. It’s just not easy to make those rigid lines,” she said.

Her response for critics who accuse her of using Catholic symbols to promote her ideology?

“Of course, that’s what I’m doing,” Carmona said. “This is propaganda. I’m a propagandist. I want you to reflect. I want you to question.

“Not only do I think of (the Virgin of Guadalupe) as a symbol of Catholicism, I think about it as going outside seeing her on tienditas (convenience stores), on graffiti, or on a tattoo of a person. It’s just an image that pertains to so much more of our culture than the religion itself,” Carmona said.

Indigenous dance and mariachi: New York celebrates Our Lady of Guadalupe

NEW YORK (RNS) — The events highlighted the cultural, as well as the religious, importance of Our Lady of Guadalupe among the city’s diverse Latin American communities.

People process with a statue of Our Lady of Guadalupe from St. Bernard Church to St. Patrick's Cathedral during Feast of Our Lady of Guadalupe festivities in New York City, early Thursday, Dec. 12, 2024. (RNS photo/Fiona Murphy)

Fiona Murphy

December 12, 202

(RNS) — Thousands gathered in New York City over the past two days to honor Our Lady of Guadalupe, the beloved patron saint of Mexico and a powerful symbol of unity and Catholic faith across Mexico and Central America.

The festivities began Wednesday evening (Dec. 11) with mariachi music and traditional Mexican folk dance, followed the next morning by a miles-long procession, or “carrera,” and a Spanish-language Mass at St. Patrick’s Cathedral.

The events highlighted the cultural, as well as the religious, importance of Our Lady of Guadalupe among the city’s diverse Latin American communities. People of Mexican descent make up one of the largest subgroups of Latino residents in New York City, according to 2022 data from the CUNY Center for Latin American Studies

Our Lady of Guadeloupe “is a symbol of our faith,” said the Rev. Jesus Ledezma, pastor of Our Lady of Guadalupe in San Bernardo Church in Lower Manhattan. “Even if you are not Catholic, you can still be considered ‘Guadalupano.’”

Procession Photos

By Fiona Murphy · December 12, 2024

In December 1531, the Virgin Mary is said to have appeared to Juan Diego, an Indigenous man, on the Tepeyac Hill, now in Mexico City. The shimmering figure, often described as having dark brown skin, revealed herself as a compassionate mother and left a miraculous image on Diego’s tilma, a cloak made of cactus fibers.

“At the time, Mexicans were waiting for the arrival of the fifth sun god, but when Lady Guadalupe came, she told them this is the true God,” said Rodolfo Nestor, a procession volunteer and student studying the history of the Lady of Guadalupe at St. Ignatius Church in Manhattan. “It was the beginning of the new world.”

The image on Juan Diego’s tilma incorporates Indigenous colors, and the flowers on her dress, the stars on her mantle and her position atop the moon blend Aztec iconography with Catholic motifs.

“The image is written in a code Indigenous people could understand,” Nestor said.

People pray at The Church of Our Lady of Guadalupe and St. Bernard prior to a Feast of Our Lady of Guadalupe procession to St. Patrick’s Cathedral in New York City, early Thursday, Dec. 12, 2024. (RNS photo/Fiona Murphy)

On Thursday morning, people gathered at the Church of Our Lady of Guadalupe and St. Bernard on 14th street in Manhattan to participate in the procession, emulating their Indigenous ancestors who, according to tradition, “ran” to the hill where Juan Diego saw Mary.

“The procession is growing every year,” said Ledezma, who has led the church since 2020. “We had 1,700 people come last year and now more than 2,100 from 19 different parishes including from the Bronx, Yonkers, Mount Vernon and more upstate. It’s very exciting.”

Nearly every participant wore clothing adorned with a symbol of the Virgin Mary and a rotating group carried a large devotional statue of Our Lady of Guadalupe. With a mariachi band leading the way, the procession started off for St. Patrick’s, on 51st Street.

“My legs are tired,” a woman carrying a bouquet of roses exclaimed as she climbed the stairs of the church around 10 a.m.

At St. Patrick’s, Archbishop of New York Timothy Dolan and the Auxiliary Bishop Francisco Figueroa Cervantes, who flew in from Mexico specifically for the day’s festivities, celebrated a Mass.

“Traditional Mañanitas” Photos

By Fiona Murphy · December 12, 2024

The cathedral floor was still strewn with rose petals left from the previous evening’s “traditional Mañanitas,” a high-energy celebration of Mexican culture and devotion. Despite the December cold and persistent rain outside the cathedral, about 400 people gathered to enjoy mariachi music and traditional dance representing various regions of Mexico.

The first high trumpet note rang out from Mariachi Tapatío de Álvaro Paulino, a band of 10 musicians based in New York. The crowd quickly pulled out their phones, and Brenda Nunez, joined by her sister Elvira, began singing along to the music. The Academia de Mariachi Nuevo Amanecer also performed mariachi tunes.

AdChoicesSponsored

“My sister wanted me to wear a more traditional Mexican dress like hers,” Brenda said, motioning to her sister’s white cotton dress embroidered with pink and orange designs. “I have one in red, but I am just coming from work so I didn’t want to wear it.” Brenda said some of her family would be walking in the procession on Thursday morning, but she would be home watching the children. “It’s very early,” Brenda said.

Rosalía León Oviedo, a singer from Mexico City, sat in the front row of the choir with her friend Rosa Maria Tellez, both in shawls embroidered with the image of Our Lady of Guadalupe. “This is my first time here,” León said. “It’s an expensive flight, but my friend (Rosa) lives in the city and invited me, and I couldn’t refuse.”

Rosalía León Oviedo wears an Our Lady of Guadalupe shawl while attending “traditional Mañanitas” at St. Patrick’s Cathedral in New York City, Dec. 11, 2024.

(RNS photo/Fiona Murphy)

Traditional folk dances were performed by the Ballet Folklórico Mexicano de Nueva York, along with the Tecuanes Quetzalcoatl, which showcased a young boy dressed as a fierce jaguar sauntering down the cathedral’s long central aisle and snapping a bullwhip, symbolizing the Indigenous tradition of jaguar hunting.

The evening concluded with the entire congregation singing “Las Mañanitas,” a popular Mexican song, and participants offering personal dedications to the image of Our Lady of Guadalupe, which sat atop the altar, surrounded by blood-red roses.

Traditional folk dances were performed by the Ballet Folklórico Mexicano de Nueva York, along with the Tecuanes Quetzalcoatl, which showcased a young boy dressed as a fierce jaguar sauntering down the cathedral’s long central aisle and snapping a bullwhip, symbolizing the Indigenous tradition of jaguar hunting.

The evening concluded with the entire congregation singing “Las Mañanitas,” a popular Mexican song, and participants offering personal dedications to the image of Our Lady of Guadalupe, which sat atop the altar, surrounded by blood-red roses.

No comments:

Post a Comment