Hospitals, farms, classrooms and local businesses feel the impact of fewer arrivals as labour gaps widen communities, thin out and the US economy faces slower growth pressures

Lydia Depillis,

Campbell Robertson

Published 29.12.25

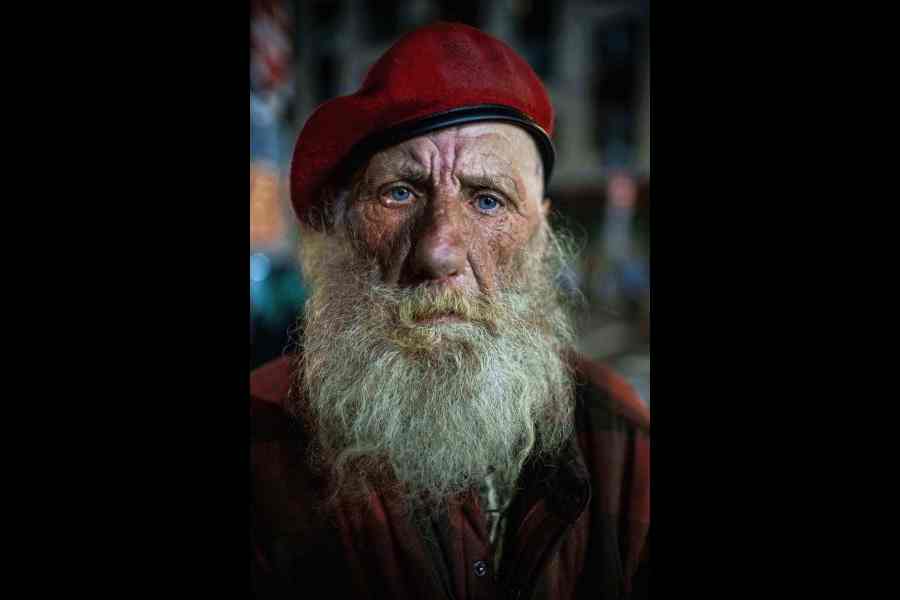

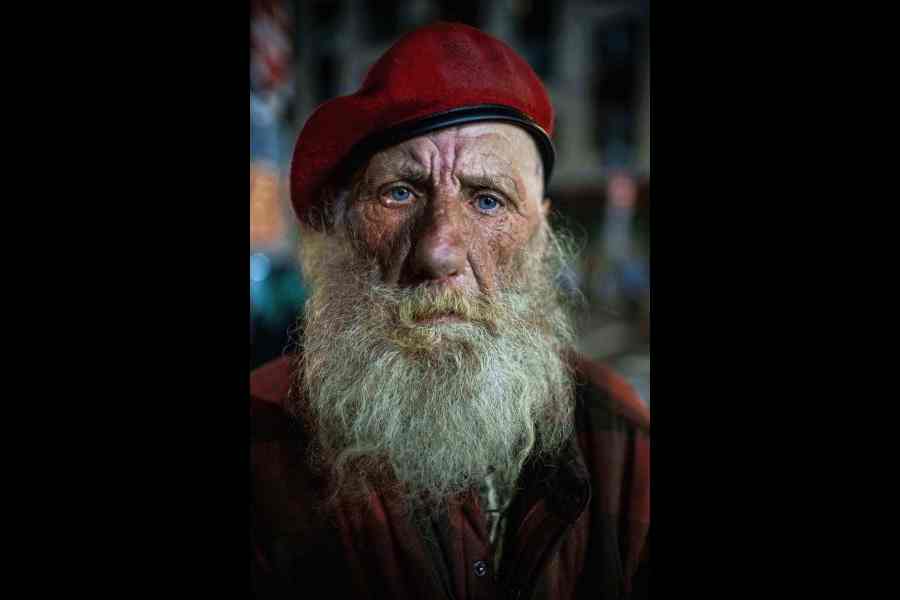

Eugene Graham watches as protesters stand off against police at a US Immigration and Customs Enforcement facility in Portland, Oregon, on October 5.AP

Across the US, someone is missing.

One year into President Donald Trump’s immigration crackdown, construction firms in Louisiana are scrambling to find carpenters. Hospitals in West Virginia have lost out on doctors and nurses who were planning to come from overseas. A neighbourhood football league in Memphis cannot field enough teams because immigrant children have stopped showing up.

America is closing its doors to the world, sealing the border, squeezing the legal avenues to entry and sending new arrivals and longtime residents to the exits.

Visa fees have been jacked up, refugee admissions are almost zero and international student admissions have dropped. The rollback of temporary legal statuses granted under the Biden administration has rendered hundreds of thousands more people newly vulnerable to removal at any time. The administration says it has already expelled more than 600,000 people.

Shrinking the foreign-born population won’t happen overnight. Oxford Economics estimates that net immigration is running at about 450,000 people a year under current policies. That is well below the two million to three million a year who came in under the Biden administration. The share of the country’s population that is foreign-born hit 14.8 per cent in 2024, a high not seen since 1890.

But White House officials have made clear they are aiming for something closer to the immigration shutdown of the 1920s, when Congress, at the crest of a decades-long surge in nativism, barred entry of people from half of the world and brought net immigration down to zero. The share of the foreign-born population bottomed out at 4.7 per cent in 1970.

There’s little doubt that major changes are in store. Immigration has woven itself so tightly through the country’s fabric — in classrooms and hospital wards, city parks and concert halls, corporate boardrooms and factory floors — that walling off the country now will profoundly alter daily life for millions of Americans.

Grocery stores and churches are quieter in immigrant neighbourhoods. Fewer students show up in Los Angeles and New York City. In South Florida, Billo’s Caracas Boys, a Venezuelan orchestra, puts on an annual holiday concert where generations of families come to dance salsas and paso dobles. This year, the orchestra announced at the last minute that it was cancelling the show because so many people are nervous about leaving home.

The changes will also be felt hundreds of kilometres from any ocean or national border, even in the snow-washed streets of Marshalltown, Iowa.

First Mexicans, some undocumented, came to Marshalltown in the 1990s to work at the pork processing plant. After a high-profile immigration raid there in 2006, refugees with more solid legal status arrived from Myanmar, Haiti and the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Now, Mexican, Chinese and Vietnamese restaurants dot the blocks around the grand, 19th-century courthouse. The population is 19 per cent foreign-born, and some 50 dialects are spoken in the public schools. The pews at the Spanish-language Mass at the local Catholic church overflow on Sundays, and, in 2021, a Burmese religious society built a towering statue of Buddha on the outskirts of town.

“You have more energy in the community,” said Michael Ladehoff, Marshalltown’s mayor-elect. “If you stay stagnant, and you don’t have new people coming to your community, you start ageing out.”

But with Trump’s crackdown on immigration gaining strength, local festivals are more thinly attended. Parents pull their children out of school when they hear about people being detained. The supervisor overseeing the construction of a high school sports stadium received a deportation letter, creating a conspicuous absence as the work finished up. The pork plant has let workers go as their work permits have expired.

Echo of past

Over the country’s first century, immigration was essentially unrestricted at the federal level. This began to change in the late 1800s, with the “great wave” of immigrants fleeing political oppression or seeking work. Starting in the 1870s and over the decades that followed, Congress barred criminals, anarchists, the indigent and all Chinese labourers.

By the turn of the 20th century, anti-immigrant sentiment was rampant.

Evidence is mixed on the effect of the 1920s restrictions on assimilation. Some researchers have found that, without newcomers arriving from their home countries, immigrants were more likely to marry American-born citizens and less likely to live in ethnically homogenous neighbourhoods.

Although the effects of the 1924 immigration restrictions are difficult to untangle from other developments — wars, technological advancements, the baby boom — wages rose for US-born workers in places affected by the immigrant restrictions. But only briefly. Employers avoided paying more by hiring workers from Mexico and Canada, countries not subject to immigration caps; American-born workers from small towns migrated to urban areas and alleviated shortages. Farms turned to automation to replace the missing labour. The coal mining industry, which was powered by immigrants now barred from entry, shrank.

And today? Construction wages have been rising, even as home building has been sluggish — a potential indication that deportations in the immigrant-heavy industry are bidding up salaries. The union representing workers in the pork processing industry sees an upside, too.

“I will certainly bring it up at the bargaining table that the way to solve a labour shortage is to pay more money,” said Mark Lauritsen, head of the meatpacking division at the United Food and Commercial Workers Union International.

The same is true in landscaping. Immigrant crews, working outside, were an easy deportation target over the summer. Come spring, said Kim Hartmann, an executive at a Chicago-area landscaping firm, the labour force could be 10 to 20 per cent smaller.

“It’s going to be much more competitive to find that individual who’s been a

foreman or a supervisor and has years of experience,” Hartmann said. “We know that drives costs up.”

Hands still matter

Many services still require humans, in person.

“If you’re an obstetrician, delivering a baby right in the moment, you need hands to lay on the patient,” said David Goldberg, a vice-president of Vandalia Health, a network of hospitals and medical offices in West Virginia.

Nearly a fifth of nursing positions are currently vacant in West Virginia — a state that is older, sicker and poorer than most — and the state faces a serious shortage of physicians in the coming years. The answer has been to look abroad. A third of West Virginia’s physicians graduated from medical schools overseas. Now that option is narrowing.

Similarly, nobody has figured out how to harvest delicate crops with machines.

“It’s not going to hop from the ground into a package without somebody’s hands being involved somewhere along the way,” said Luke Brubaker, who runs a dairy farm in Pennsylvania. To milk cows, feed them and deliver calves, he relies on more than a dozen foreign-born workers, most of them Mexican. He is not optimistic that he will be able to replace them.

Land of opportunity?

Dan Simpson, the chief executive of Taziki’s, a fast casual Mediterranean restaurant chain based in the Southeast, has been losing employees since the beginning of the year. These were not only dishwashers and cooks but also managers and assistant managers, who had come to the US with advanced degrees.

“If you zoom back, the bigger problem is that we’re tarnishing the brand of America,” Simpson said. Even if the United States opens up again, he said, “we’re going to need a campaign to fix the idea that America is not the land of opportunity.”

International students pay full-freight tuition that helps fund new programmes and basic costs at many US colleges. As international enrollment has dropped, many schools are facing budget holes.

Nearly half of the immigrants who legally came to the US from 2018 to 2022 were college-educated, according to the Migration Policy Institute, a nonpartisan think tank. Immigrants are far more likely than US citizens to start businesses; nearly half of this year’s Fortune 500 companies were founded by immigrants or the children of immigrants.

“You have an economy that is smaller, less dynamic and less diversified,” said Exequiel Hernandez, a professor at the Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania.

Over the longer term, low immigration will collide with one inexorable trend: an ageing population in need of care just as fewer workers are available to provide it.

New York Times News Service

Eugene Graham watches as protesters stand off against police at a US Immigration and Customs Enforcement facility in Portland, Oregon, on October 5.AP

Across the US, someone is missing.

One year into President Donald Trump’s immigration crackdown, construction firms in Louisiana are scrambling to find carpenters. Hospitals in West Virginia have lost out on doctors and nurses who were planning to come from overseas. A neighbourhood football league in Memphis cannot field enough teams because immigrant children have stopped showing up.

America is closing its doors to the world, sealing the border, squeezing the legal avenues to entry and sending new arrivals and longtime residents to the exits.

Visa fees have been jacked up, refugee admissions are almost zero and international student admissions have dropped. The rollback of temporary legal statuses granted under the Biden administration has rendered hundreds of thousands more people newly vulnerable to removal at any time. The administration says it has already expelled more than 600,000 people.

Shrinking the foreign-born population won’t happen overnight. Oxford Economics estimates that net immigration is running at about 450,000 people a year under current policies. That is well below the two million to three million a year who came in under the Biden administration. The share of the country’s population that is foreign-born hit 14.8 per cent in 2024, a high not seen since 1890.

But White House officials have made clear they are aiming for something closer to the immigration shutdown of the 1920s, when Congress, at the crest of a decades-long surge in nativism, barred entry of people from half of the world and brought net immigration down to zero. The share of the foreign-born population bottomed out at 4.7 per cent in 1970.

There’s little doubt that major changes are in store. Immigration has woven itself so tightly through the country’s fabric — in classrooms and hospital wards, city parks and concert halls, corporate boardrooms and factory floors — that walling off the country now will profoundly alter daily life for millions of Americans.

Grocery stores and churches are quieter in immigrant neighbourhoods. Fewer students show up in Los Angeles and New York City. In South Florida, Billo’s Caracas Boys, a Venezuelan orchestra, puts on an annual holiday concert where generations of families come to dance salsas and paso dobles. This year, the orchestra announced at the last minute that it was cancelling the show because so many people are nervous about leaving home.

The changes will also be felt hundreds of kilometres from any ocean or national border, even in the snow-washed streets of Marshalltown, Iowa.

First Mexicans, some undocumented, came to Marshalltown in the 1990s to work at the pork processing plant. After a high-profile immigration raid there in 2006, refugees with more solid legal status arrived from Myanmar, Haiti and the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Now, Mexican, Chinese and Vietnamese restaurants dot the blocks around the grand, 19th-century courthouse. The population is 19 per cent foreign-born, and some 50 dialects are spoken in the public schools. The pews at the Spanish-language Mass at the local Catholic church overflow on Sundays, and, in 2021, a Burmese religious society built a towering statue of Buddha on the outskirts of town.

“You have more energy in the community,” said Michael Ladehoff, Marshalltown’s mayor-elect. “If you stay stagnant, and you don’t have new people coming to your community, you start ageing out.”

But with Trump’s crackdown on immigration gaining strength, local festivals are more thinly attended. Parents pull their children out of school when they hear about people being detained. The supervisor overseeing the construction of a high school sports stadium received a deportation letter, creating a conspicuous absence as the work finished up. The pork plant has let workers go as their work permits have expired.

Echo of past

Over the country’s first century, immigration was essentially unrestricted at the federal level. This began to change in the late 1800s, with the “great wave” of immigrants fleeing political oppression or seeking work. Starting in the 1870s and over the decades that followed, Congress barred criminals, anarchists, the indigent and all Chinese labourers.

By the turn of the 20th century, anti-immigrant sentiment was rampant.

Evidence is mixed on the effect of the 1920s restrictions on assimilation. Some researchers have found that, without newcomers arriving from their home countries, immigrants were more likely to marry American-born citizens and less likely to live in ethnically homogenous neighbourhoods.

Although the effects of the 1924 immigration restrictions are difficult to untangle from other developments — wars, technological advancements, the baby boom — wages rose for US-born workers in places affected by the immigrant restrictions. But only briefly. Employers avoided paying more by hiring workers from Mexico and Canada, countries not subject to immigration caps; American-born workers from small towns migrated to urban areas and alleviated shortages. Farms turned to automation to replace the missing labour. The coal mining industry, which was powered by immigrants now barred from entry, shrank.

And today? Construction wages have been rising, even as home building has been sluggish — a potential indication that deportations in the immigrant-heavy industry are bidding up salaries. The union representing workers in the pork processing industry sees an upside, too.

“I will certainly bring it up at the bargaining table that the way to solve a labour shortage is to pay more money,” said Mark Lauritsen, head of the meatpacking division at the United Food and Commercial Workers Union International.

The same is true in landscaping. Immigrant crews, working outside, were an easy deportation target over the summer. Come spring, said Kim Hartmann, an executive at a Chicago-area landscaping firm, the labour force could be 10 to 20 per cent smaller.

“It’s going to be much more competitive to find that individual who’s been a

foreman or a supervisor and has years of experience,” Hartmann said. “We know that drives costs up.”

Hands still matter

Many services still require humans, in person.

“If you’re an obstetrician, delivering a baby right in the moment, you need hands to lay on the patient,” said David Goldberg, a vice-president of Vandalia Health, a network of hospitals and medical offices in West Virginia.

Nearly a fifth of nursing positions are currently vacant in West Virginia — a state that is older, sicker and poorer than most — and the state faces a serious shortage of physicians in the coming years. The answer has been to look abroad. A third of West Virginia’s physicians graduated from medical schools overseas. Now that option is narrowing.

Similarly, nobody has figured out how to harvest delicate crops with machines.

“It’s not going to hop from the ground into a package without somebody’s hands being involved somewhere along the way,” said Luke Brubaker, who runs a dairy farm in Pennsylvania. To milk cows, feed them and deliver calves, he relies on more than a dozen foreign-born workers, most of them Mexican. He is not optimistic that he will be able to replace them.

Land of opportunity?

Dan Simpson, the chief executive of Taziki’s, a fast casual Mediterranean restaurant chain based in the Southeast, has been losing employees since the beginning of the year. These were not only dishwashers and cooks but also managers and assistant managers, who had come to the US with advanced degrees.

“If you zoom back, the bigger problem is that we’re tarnishing the brand of America,” Simpson said. Even if the United States opens up again, he said, “we’re going to need a campaign to fix the idea that America is not the land of opportunity.”

International students pay full-freight tuition that helps fund new programmes and basic costs at many US colleges. As international enrollment has dropped, many schools are facing budget holes.

Nearly half of the immigrants who legally came to the US from 2018 to 2022 were college-educated, according to the Migration Policy Institute, a nonpartisan think tank. Immigrants are far more likely than US citizens to start businesses; nearly half of this year’s Fortune 500 companies were founded by immigrants or the children of immigrants.

“You have an economy that is smaller, less dynamic and less diversified,” said Exequiel Hernandez, a professor at the Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania.

Over the longer term, low immigration will collide with one inexorable trend: an ageing population in need of care just as fewer workers are available to provide it.

New York Times News Service

No comments:

Post a Comment