November 28, 2021·

Supporters of former President Trump are seen the North Carolina Republican Party Convention on June 5

The Republican Party is becoming a cult. Its leaders are in thrall to Donald Trump, a defeated former president who refuses to acknowledge defeat. Its ideology is MAGA, Trump's deeply divisive take on what Republicans assume to be unifying American values.

The party is now in the process of carrying out purges of heretics who do not worship Trump or accept all the tenets of MAGA. Conformity is enforced by social media, a relatively new institution with the power to marshal populist energy against critics and opponents.

What's happening on the right in American politics is not exactly new. To understand it, you need to read a book published 50 years ago by Seymour Martin Lipset and Earl Raab, "The Politics of Unreason: Right-Wing Extremism in America, 1790-1970." Right-wing extremism, now embodied in Trump's MAGA movement, dates back to the earliest days of the country.

The title of Lipset and Raab's book was chosen carefully. Right-wing extremism is not about the rational calculation of interests. It's about irrational impulses, which the authors identify as "status frustrations." They write that "the political movements which have successfully appealed to status resentments have been irrational in character. [The movements] focus on attacking a scapegoat, which conveniently symbolizes the threat perceived by their supporters."

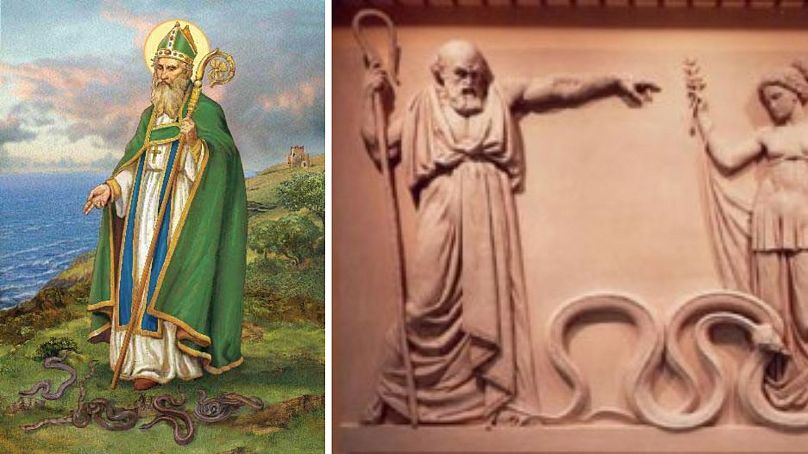

The most common scapegoats have been minority ethnic or religious groups. In the 19th century, that meant Catholics, immigrants and even Freemasons. The Anti-Masonic Party, the Know Nothing Party and later the American Protective Association were major political forces. In the 20th century, the U.S. experienced waves of anti-immigrant sentiment. After World War II, anti-communism became the driving force behind McCarthyism in the 1950s and the Goldwater movement in the early 1960s ("Extremism in the defense of liberty is no vice").

The roots of the current right-wing extremism lie in the late 1960s and 1970s, when Americans began to be polarized over values (race, ethnicity, sex, military intervention). Conflicts of interest (such as business versus labor) can be negotiated and compromised. Conflicts of values cannot.

You see "the politics of unreason" in today's right-wing extremism. While it remains true, as it has been for decades, that the wealthier you are, the more likely you are to vote Republican (that's interests), what's new today is that the better educated you are, the more likely you are to vote Democratic, at least among whites (that's values, and it's been driving white suburban voters with college degrees away from Trump's "know-nothing" brand of Republicanism).

Oddly, religion has become a major force driving the current wave of right-wing extremism. Not religious affiliation (Protestant versus Catholic) but religiosity (regular churchgoers versus non-churchgoers). That's not because of Trump's religious appeal (he has none) but because of the Democratic Party's embrace of secularism and the resulting estrangement of fundamentalist Protestants, observant Catholics and even orthodox Jews.

The Democratic Party today is defined by its commitment to diversity and inclusion. The party celebrates diversity in all its forms - racial, ethnic, religious and sexual. To Democrats, that's the tradition of American pluralism - "E pluribus unum." Republicans celebrate the "unum" more than the "pluribus" - we may come from diverse backgrounds, but we should all share the same "American values."

One reason right-wing extremism is thriving in the Republican Party is that there is no figure in the party willing to lead the opposition to it. Polls of Republican voters show no other GOP figure even close to Trump's level of support for the 2024 GOP presidential nomination. The only other Republican who seems interested in running is Gov. Larry Hogan of Maryland, who recently criticized "Trump cancel culture."

If Trump does run in 2024, as he seems inclined to do, can he win?

It all depends on President Biden's record. Right now, Biden's popularity is not very high. In fact, Biden and Trump are about equally unpopular (Biden's job approval is 52 to 43 percent negative, while Trump's favorability is 54 to 41.5 percent negative). Biden will be 82 years old in 2024. If he doesn't run, the Democrats will very likely nominate Vice President Harris. When a president doesn't run for reelection, his party almost always nominates its most recent vice president, assuming they run (Richard Nixon in 1960, Hubert Humphrey in 1968, Walter Mondale in 1984, George H.W. Bush in 1988, Al Gore in 2000, Joe Biden in 2020). Democrats would be unlikely to deny a black woman the nomination. There is also some talk of Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg running if Biden doesn't.

The 2024 election could be a rematch between Trump and Biden. Or a race between Trump and a black woman. Or between Trump and a gay man with a husband and children. Lee Drutman, a political scientist at the New America think tank, recently told The New York Times, "I have a hard time seeing how we have a peaceful 2024 election after everything that's happened now. I don't see the rhetoric turning down. I don't see the conflicts going away. ... It's hard to see how it gets better before it gets worse."

Bill Schneider is an emeritus professor at the Schar School of Policy and Government at George Mason University and author of "Standoff: How America Became Ungovernable" (Simon & Schuster).

From xenophobia to conspiracy theories, the Know Nothing party launched a nativist movement whose effects are still felt today

Lorraine Boissoneault

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/fc/2d/fc2d8316-33df-49ee-b171-3b9a52545564/cwbwma.jpg)

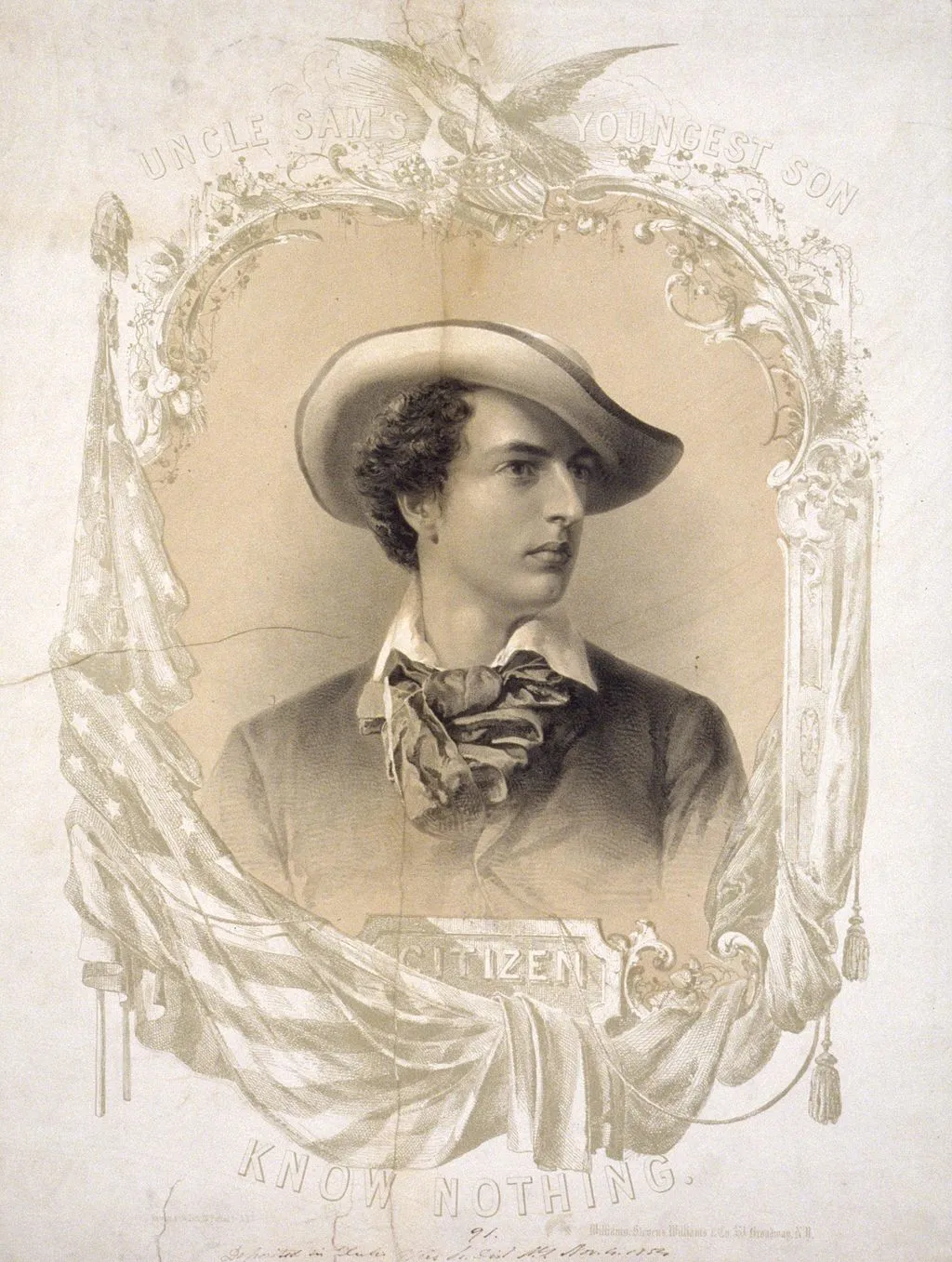

Like Fight Club, there were rules about joining the secret society known as the Order of the Star Spangled Banner (OSSB). An initiation rite called “Seeing Sam.” The memorization of passwords and hand signs. A solemn pledge never to betray the order. A pureblooded pedigree of Protestant Anglo-Saxon stock and the rejection of all Catholics. And above all, members of the secret society weren’t allowed to talk about the secret society. If asked anything by outsiders, they would respond with, “I know nothing.”

So went the rules of this secret fraternity that rose to prominence in 1853 and transformed into the powerful political party known as the Know Nothings. At its height in the 1850s, the Know Nothing party, originally called the American Party, included more than 100 elected congressmen, eight governors, a controlling share of half-a-dozen state legislatures from Massachusetts to California, and thousands of local politicians. Party members supported deportation of foreign beggars and criminals; a 21-year naturalization period for immigrants; mandatory Bible reading in schools; and the elimination of all Catholics from public office. They wanted to restore their vision of what America should look like with temperance, Protestantism, self-reliance, with American nationality and work ethic enshrined as the nation's highest values.

Paving the way for the Know Nothing movement were two men from New York City. Thomas R. Whitney, the son of a silversmith who opened his own shop, wrote the magnum opus of the Know Nothings, A Defense of the American Policy. William “Bill the Butcher” Poole was a gang leader, prizefighter and butcher in the Bowery (and would later be used as inspiration for the main character in Martin Scorsese’s Gangs of New York). Whitney and Poole were from different social classes, but both had an enormous impact on their chosen party—and their paths crossed at a pivotal moment in the rise of nativism.

In addition to being a successful engraver, Whitney was an avid reader of philosophy, history and classics. He moved from reading to writing poetry and, eventually, political tracts. “What is equality but stagnation?” Whitney wrote in one of them. Preceded in nativist circles by such elites as author James Fenimore Cooper, Alexander Hamilton, Jr. and James Monroe (nephew of the former president), Whitney had a knack for rising quickly to the top of whichever group he belonged to. He became a charter member of the Order of United Americans (the precursor to the OSSB) and used his own printing press to publish many of the group’s pamphlets.

Whitney believed in government action, but not in service of reducing social inequality. Rather, he believed, all people “are entitled to such privileges, social and political, as they are capable of employing and enjoying rationally.” In other words, only those with the proper qualifications deserved full rights. Women’s suffrage was abhorrent and unnatural, Catholics were a threat to the stability of the nation, and German and Irish immigrants undermined the old order established by the Founding Fathers.

From 1820 to 1845, anywhere from 10,000 to 1000,000 immigrants entered the U.S. each year. Then, as a consequence of economic instability in Germany and a potato famine in Ireland, those figures turned from a trickle into a tsunami. Between 1845 and 1854, 2.9 million immigrants poured into the country, and many of them were of Catholic faith. Suddenly, more than half the residents of New York City were born abroad, and Irish immigrants comprised 70 percent of charity recipients.

As cultures clashed, fear exploded and conspiracies abounded. Posters around Boston proclaimed, “All Catholics and all persons who favor the Catholic Church are…vile imposters, liars, villains, and cowardly cutthroats.” Convents were said to hold young women against their will. An “exposé” published by Maria Monk, who claimed to have gone undercover in one such convent, accused priests of raping nuns and then strangling the babies that resulted. It didn’t matter that Monk was discovered as a fraud; her book sold hundreds of thousands of copies. The conspiracies were so virulent that churches were burned, and Know Nothing gangs spread from New York and Boston to Philadelphia, Baltimore, Louisville, Cincinnati, New Orleans, St. Louis and San Francisco.

At the same time as this influx of immigrants reshaped the makeup of the American populace, the old political parties seemed poised to fall apart.

“The Know Nothings came out of what seemed to be a vacuum,” says Christopher Phillips, professor of history at University of Cincinnati. “It’s the failing Whig party and the faltering Democratic party and their inability to articulate, to the satisfaction of the great percentage of their electorate, answers to the problems that were associated with everyday life.”

Citizen Know Nothing. Wikimedia Commons

Phillips says the Know Nothings displayed three patterns common to all other nativist movements. First is the embrace of nationalism—as seen in the writings of the OSSB. Second is religious discrimination: in this case, Protestants against Catholics rather than the more modern day squaring-off of Judeo-Christians against Muslims. Lastly, a working-class identity exerts itself in conjunction with the rhetoric of upper-class political leaders. As historian Elliott J. Gorn writes, “Appeals to ethnic hatreds allowed men whose livelihoods depended on winning elections to sidestep the more complex and politically dangerous divisions of class.”

No person exemplified this veneration of the working class more than Poole. Despite gambling extravagantly and regularly brawling in bars, Poole was a revered party insider, leading a gang that terrorized voters at polling places in such a violent fashion that one victim was later reported to have a bite on his arm and a severe eye injury. Poole was also the Know Nothings’ first martyr.

On February 24, 1855, Poole was drinking at a New York City saloon when he came face to face with John Morrissey, an Irish boxer. The two exchanged insults and both pulled out guns. But before the fight could turn violent, police arrived to break it up. Later that night, though, Poole returned to the hall and grappled with Morrissey's men, including Lewis Baker, a Welsh-born immigrant, who shot Poole in the chest at close range. Although Poole survived for nearly two weeks, he died on March 8. The last words he uttered pierced the hearts of the country’s Know Nothings: “Goodbye boys, I die a true American.”

Approximately 250,000 people flooded lower Manhattan to pay their respects to the great American. Dramas performed across the country changed their narratives to end with actors wrapping themselves in an American flag and quoting Poole’s last words. An anonymous pamphlet titled The Life of William Poole claimed that the shooting wasn’t a simple barroom scuffle, but an assassination organized by the Irish. The facts didn’t matter; that Poole had been carrying a gun the night of the shooting, or that his assailant took shots to the head and abdomen, was irrelevant. Nor did admirers care that Poole had a prior case against him for assault with intent to kill. He was an American hero, “battling for freedom’s cause,” who sacrificed his life to protect people from dangerous Catholic immigrants.

|

| COUNT THE STEREOTYPES |

On the day of Poole’s funeral, a procession of 6,000 mourners trailed through the streets of New York. Included in their number were local politicians, volunteer firemen, a 52-piece band, members of the OSSB—and Thomas R. Whitney, about to take his place in the House of Representatives as a member of the Know Nothing Caucus.

Judging by the size of Poole’s funeral and the Know Nothing party’s ability to penetrate all levels of government, it seemed the third party was poised to topple the Whigs and take its place in the two-party system. But instead of continuing to grow, the Know Nothings collapsed under the pressure of having to take a firm position on the issue the slavery. By the late 1850s, the case of Dred Scott (who sued for his freedom and was denied it) and the raids led by abolitionist John Brown proved that slavery was a more explosive and urgent issue than immigration.

America fought the Civil War over slavery, and the devastation of that conflict pushed nativist concerns to the back of the American psyche. But nativism never left, and the legacy of the Know Nothings has been apparent in policies aimed at each new wave of immigrants. In 1912, the House Committee on Immigration debated over whether Italians could be considered “full-blooded Caucasians” and immigrants coming from southern and eastern Europe were considered "biologically and culturally less intelligent."

From the end of the 19th century to the first third of the 20th, Asian immigrants were excluded from naturalization based on their non-white status. “People from a variety of groups and affiliations, ranging from the Ku Klux Klan to the Progressive movement, old-line New England aristocrats and the eugenics movement, were among the strange bedfellows in the campaign to stop immigration that was deemed undesirable by old-stock white Americans,” writes sociologist Charles Hirschman of the early 20th century. “The passage of immigration restrictions in the early 1920s ended virtually all immigration except from northwestern Europe.”

Those debates and regulations continue today, over refugees from the Middle East and immigrants from Latin America.

Phillips’s conclusion is that those bewildered by current political affairs simply haven’t looked far enough back into history. “One can’t possibly make sense of [current events] unless you know something about nativism,” he says. “That requires you to go back in time to the Know Nothings. You have to realize the context is different, but the themes are consistent. The actors are still the same, but with different names.”

Lorraine Boissoneault | | READ MORE

Lorraine Boissoneault is a contributing writer to SmithsonianMag.com covering history and archaeology. She has previously written for The Atlantic, Salon, Nautilus and others. She is also the author of The Last Voyageurs: Retracing La Salle's Journey Across America. Website: http://www.lboissoneault.com/