Jack Aylward, Ed.D.

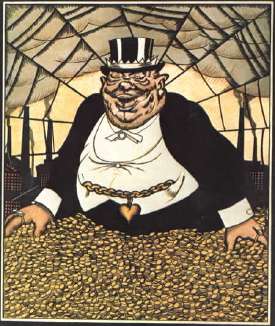

As we approach the millennium, we continue to grapple with

increasingly toxic threats such as environmental pollution, political

tyranny, and corporate domination of the human spirit. Currently, we

are witnessing the development of a health-care delivery system that not

only threatens our professional identities, but ultimately could create a

repressive definition of mental health that replicates the one against

which Perls, Hefferline, and Goodman originally rebelled. Gestalt therapy

theory places importance on creativity, novelty, spontaneity, and

risk in a society that is moving ever closer to repetition, obedience, and

the illusion of security. To meet the challenges, we need not say or do

anything new but simply restate (perhaps more loudly) what is already

present in our literature. To do so, it is imperative that we once again

apply our theoretical model to sociopolitical issues and realities that

contribute to the individual boundary disturbances we deal with in our

psychotherapeutic practices. In this spirit we will sequentially review: (1)

the theoretical and clinical definitions of contact boundary phenomena,

(2) the social nature of self-functioning, and (3) the political implications

in the writings of Paul Goodman.

Given a psychological model that views the individual as innately

healthy and capable, with pathology as a secondary disruption of an

otherwise natural homeostatic equilibrium, Goodman's anarchistic

philosophy is especially resonant with Gestalt therapy theory. This

connection between philosophy and therapy is not unlike Erich Frornrn's

belief in Marxist socialism. For him this philosophy "meant a society

which provides the material basis for the full development of the

individual, for the unfolding of all his human powers, for his full

independence" (Fromm, 1956, p. xiv). In both Fromm and Goodman we

see the belief that society should provide the support for an individual

who is and can be much, rather than one who has much. Optimally,

Goodman envisioned a dynamic unity of human need and social

support, implying as McLeod (1993) does that "the natural hierarchy of

needs arising to seek their fulfillment in the contact that is our very self

means Gestalt is a profoundly social therapy, envisioning and declaring

the naturalness of social and environmental harmony" (p. 28).

In subsequent essays and articles, Goodman focused on political realities

and how such phenomena affected contact boundary functioning.

Far from a utopian view Goodman's view of formal governmental

bureaucracy was that less was more with respect to social and political

structure and its impact on the quality of individual life. Susan Sontag

(1988) described Goodman's social outlook as "a form of conservative

humanistic thinking-doggedly sensitive to everything repressive and

mean while remaining loyal to the limits that protect human growth and

pleasure" (p. xvii). In this sense, Goodman saw that contact boundary

disturbances emanating from repressive and overly developed social

organizations have the potential to sap the spontaneity from human

functioning. Goodman (1994) stated that "society with a big S can do

very little for people except to be tolerable, so they can go on about the

more important business of life" (p. 53). Given that human selfhood was

primarily a social process supported by communication within a community,

political structures were realities needing to be reckoned with.

Mead's conceptualization of self-functioning parallels Goodman's

thinking in this area:

the "I" requires that we protect the rights and freedoms of individuals

as extolled by liberalism, while the "ME" imposes those moral

duties, commitments, and obligations advocated by cornrnunitarianism

[Odin, 1996, p. 371.

Much of Goodman's thinking was influenced by his association with

communitarian philosophers such as Randolph Bourne, Van Wyk

Brooks, and Lewis Murnford. Along with these dissenters within the

progressive intelligentsia of the time who were disappointed in contemporary

liberalism, Goodman was wary of the alienation resulting from

the bureaucracies of advanced industrialism. He, along with Dwight

Macdonald, Dorothy Dey, and C. Wright Mills, supported Brooks's ideal

of "the crafted or interactive self, which found its autonomy by participating

in a public world of culture and experience" (Blake, 1990, p. 141).

Consistent with the process functioning of self-formation in Gestalt therapy

theory, Brooks saw the "crafted self" as a kind of conversation with

the social and natural environments. Social and political realities

provided an ongoing ground for the alienation/identification processes

of contact functioning. In Confusion and Disorder" (197%) Goodman

outlined the potential impact that social structure can have on human

distress.

But if advanced peoples have indeed been colonized by their own

advances, they are confused and have lost their ability to pick and

choose what they can assimilate. We certainly manifest a remarkable

rigidity in our social institutions, an inability to make inventive

pragmatic adjustment. And perhaps worse, the sociology and politics

that we do think up have the same technological, centralizing,

and urban style that is causing our derangement [p. 2351.

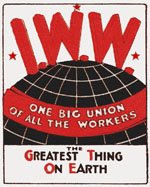

The importance Goodman placed on organismic self-regulation and

social functioning also reflected the political thinking of such anarchists

as Mikhail Bakunin and Prince Peter Kropotkin. To Goodman, anarchy

epitomized the absence of authority, not the absence of order. In his

introduction to Kropotkin's Memoirs of a Revolutionist Goodman (1968)

points out the potential for disruptive contact functioning that can result

from an overly organized and impersonal political structure:

The real enemies have proved to be the State (whose health is war),

over-centralized organization, the authoritarian personality of

people. The call is for grass-roots social structures, spontaneity and

mutual aid, direct action and doing it yourself, education for selfreliance

and agitation for freedom [p. xxi].

Goodman was sensitive to the dehumanization of the industrial

revolution, to the accompanying division of labor and, to anything that

smacked of tyranny over someone else's body. Like other anarchist

thinkers, Goodman was fanatic in his defense of the untrammeled person

whom he felt to be best nurtured by an innovative way of life and a

nonrepressive political doctrine.

In Anarchism and Revolution (1977) he wrote:

In anarchist theory, the word revolution means the process by which

the grip of authority is loosed, so that the functions of life can

regulate themselves without top-down direction or external

hindrance. The idea is that except for emergencies and a few special

cases, free functioning will find its own right structures and coordination

[p. 2151.