Jackson Browne: ‘My generation were idealistic and naive but we were right about so many things’

The singer-songwriter talks to Kevin E G Perry about his benefit album for Haiti, the calamitous state of the planet, Donald Trump’s ‘wild lies’, his fears about the election, and getting old

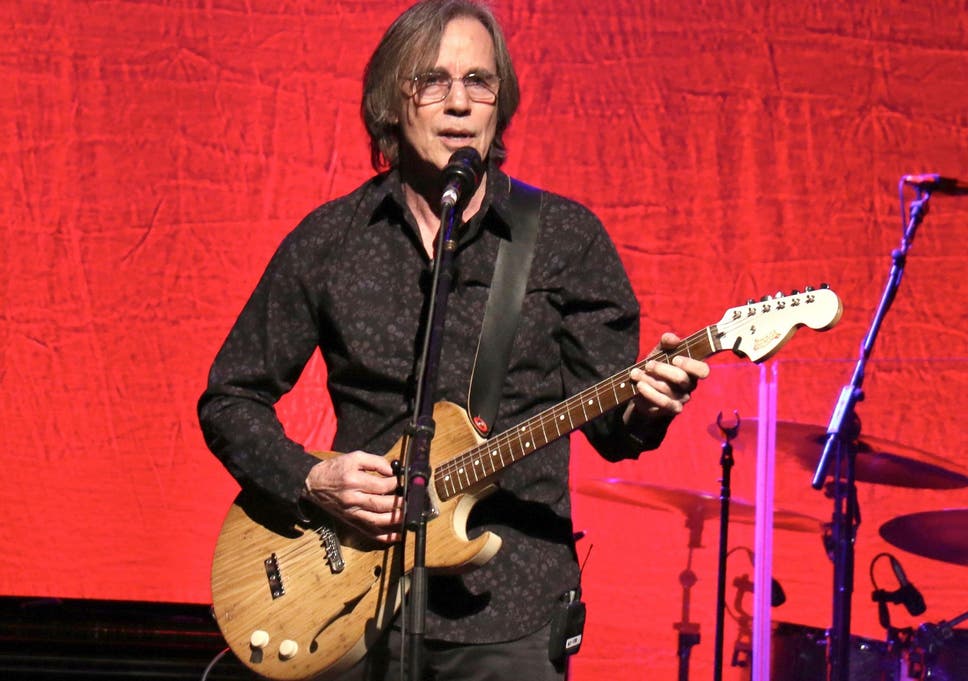

Jackson Browne performing at a benefit concert in New York, December 2019 ( Rex )

The morning after our interview I get a call from Jackson Browne. I stare at my phone in bleary-eyed confusion, trying to remember if one of the all-time great singer-songwriters had let slip anything scandalous he might be eager to recant, but when I pick up I hear his warm Californian tones overflowing with enthusiasm. “I just realised I didn’t finish telling you about Rick!”

Rick appears in the third verse of Browne’s song “Love Is Love”, the lead single from a new benefit album, Let the Rhythm Lead, which he recorded in Haiti along with a group of fellow musicians to support the charity Artists for Peace and Justice (APJ). Browne has been passionate about their work since playing a benefit concert after the devastating 2010 earthquake, and was impressed by APJ’s ability to swiftly build a school in Port-au-Prince that now provides free education to 2,600 of the most impoverished children in the western hemisphere. Moved by the stories he heard from Haiti, Browne wrote “Standing in the Breach”, the title track of his 2014 album about the disaster and the long history of colonialism and slavery that preceded it. “It’s a difficult subject, so it took me a long time to finish that song,” he says. “I think it took me longer to write than it took them to build the school.”

Browne made his name in the Seventies as a writer of deeply introspective songs about love, death and desire. He had his first hit in in March 1972 with “Doctor My Eyes”, which was soon covered by The Jackson 5. A few months later, Eagles frontman Glenn Frey completed Browne’s unfinished song “Take It Easy” and the track launched his band’s career. As rock lore has it, Browne was stuck on the line: “Well, I’m a-standin’ on a corner in Winslow, Arizona…”, before Frey provided: “Such a fine sight to see. It’s a girl, my lord, in a flatbed Ford, slowin’ down to take a look at me.”

Browne filled the remainder of the decade with a string of classic albums: 1973’s For Everyman, 1974’s Late for the Sky, 1976’s The Pretender and 1977’s Running On Empty, a portrait of life on the road which gave him his biggest commercial success. In the Eighties, Browne’s songwriting became more overtly political as he began to turn his lacerating gaze outward.

It was only when he arrived in Haiti to visit the school that APJ built that Browne learned they’d also constructed an artist’s institute in the south coast town of Jacmel, where young people were learning to become sound engineers in a modern studio. “When I saw it I thought, well, people from outside of Haiti should come here and work,” he says. “So I asked some people if they wanted to come.”

The group he rounded up included the songwriter and producer Jonathan Wilson (“A very willing partner and accomplice”) and former Rilo Kiley singer Jenny Lewis (“One of my heroes. I love her music”) as well as Paul Beaubrun, Habib Koite, Raul Rodriguez and Jonathan Russell. On the island they also teamed up with members of the Haitian roots band Lakou Mizik. They set about trying to capture the reality of the country in song, which brings us back to Rick, who Browne didn’t finish telling us about. In the song he’s riding a motorbike through the slums: “The father and the doctor to the poorest of the poor / Raising up the future from the rubble of the past”. As it turns out, he’s a real person.

“Father Rick Frechette is a major figure in this whole story,” explains Browne. “He’s a Catholic priest, but when he arrived in Haiti it was so rough he said: ‘These people don’t need a priest, they need a doctor.’ He went away, became a doctor and then came back to Haiti and built a hospital. He’s an inspiration, and he was instrumental in starting the school.”

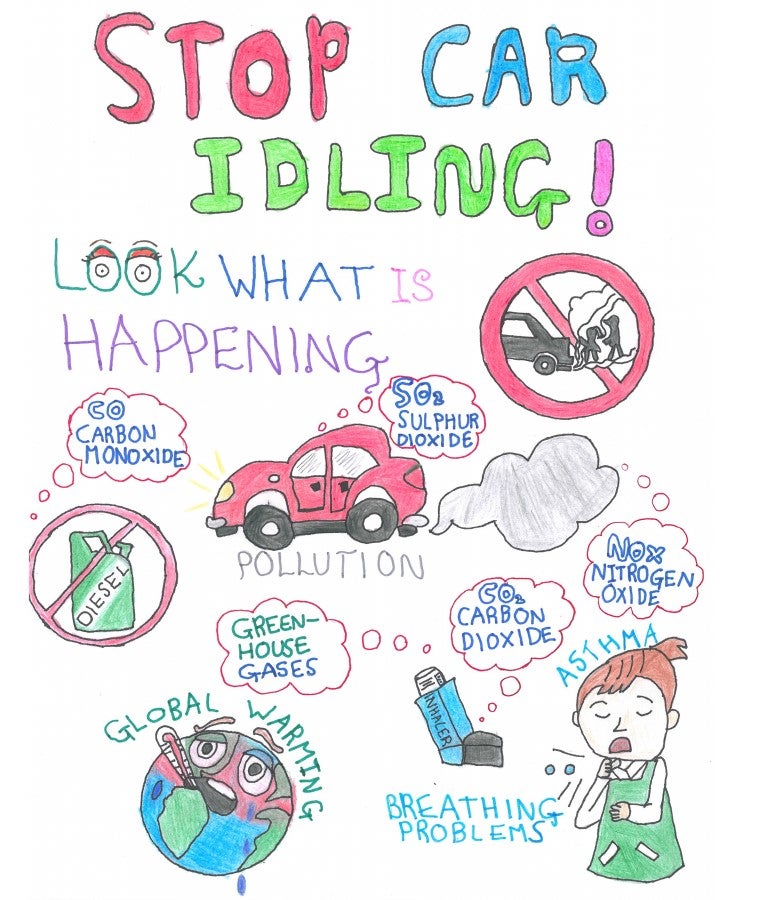

Browne’s determination to shine a light on Rick and the work still being done in Haiti is in part motivated by the knowledge that the world’s attention has long since moved on. “It’s such a vibrant culture,” he says. “But the art and music and the incredible resilience of these people is matched by the environmental problems which have come with global warming, the hurricanes and the effects of centuries of deforestation. The problems are formidable.”

Jackson Browne (fourth left) with the musicians who worked on charity album ‘Let the Rhythm Lead’

Browne is fiercely passionate about the environment. He lives in an off-grid ranch supported by wind and solar power, and since 2008 has banned plastic bottles from his tours. His 1974 song “Before the Deluge” spoke of anger at those who had forged the earth’s “beauty into power”, and warned of the “magnitude of her fury in the final hour”. It could almost have been written today, although Browne sadly points out our situation is now even more dangerous. “That song was inspired by a writer named Paul Ehrlich,” he says. “He laid forth a scenario in which the world’s dysfunctions compound and create an apocalyptic outcome, but even he couldn’t have predicted the calamitous situation we’re in now where we have a world leader who is flagrantly disregarding information from the scientific community.”

As if to underscore his point, the day we speak the Trump administration announces it is scrapping pollution protections for America’s streams and wetlands. Browne says he doesn’t believe America will re-elect their president this year, but his optimism is shaded with caution. “I don’t think it’s in the bag or anything, but I have to hope,” he says. “He didn’t win the popular vote, and he only has a 30 per cent approval rating, but that 30 per cent of people are the ones I’m worried about. I saw a photograph of him at a rally, and there was a sign saying: ‘Thank Baby Jesus for President Trump’. Holy s**t! He’s telling these wild lies and still receiving that sort of adoration.”

Read more

Louis Tomlinson: ‘Being in One Direction was like a drug’

Louis Tomlinson: ‘Being in One Direction was like a drug’All of these issues will filter into his next album, which he plans to release in September. He’s currently finishing a track called “Downhill from Everywhere”, inspired by the oceanographer Captain Charles Moore’s remark that “the ocean is downhill from everywhere”. Another new song is called “A Little Soon to Say”. He recites a few lines of it: “I want to see you holding out your light / I want to see you find your way / Beyond the sirens in the broken night / Beyond the sickness of our day / And after all we’ve come to live with / I want to know if you’re OK / I have to think it’s gonna be alright / It’s just a little soon to say.”

“That’s my way of touching upon what I’m worried about most,” he explains. “I wonder how young people coming into positions of authority in this world are going to deal with what we’re leaving them. Even as my generation were somewhat myopic or idealistic or naive, we were right about so many things. It’s the same people that opposed the Vietnam War, who wanted to protect the planet, who want to feed the hungry and educate the uneducated.”

He sees echoes of that Sixties idealism in the “very inspiring” activism of Greta Thunberg. “This generation coming into the world taking these problems seriously is exactly what’s needed,” he says. “I don’t feel I have the right to be pessimistic or feel defeated, but it’s a struggle I have every day because the news is so unremittingly bad. Activism by young people is one of the brighter spots.”

Browne in 1974 (Rex)

For Browne, America’s problems are manifold but intertwined. He brings up the failings of the criminal justice system and the unchecked power of the industrial war complex that he sang about on 1986’s “Lives in the Balance”. “This is the worry I have about democracy,” he says. “It can be gamed by private interests, whether they be robber barons in the 1800s or the fossil fuel industry today. They get us to drag our feet so they can keep making their corporate fortunes. As Warren Zevon said in his great song: our s**t’s f***ed up.”

That would be Zevon’s “My S**t’s F***ed Up”, released in 2000, which is about a man hearing bad news from his doctor. Two years later Zevon received his own terminal diagnosis, learning of the cancer that would kill him in 2003. Browne and Zevon had been friends and collaborators since the Seventies, and they shared a knack for sharply prescient songwriting. When Browne was on his most recent tour, with the headlines full of Russia’s attempts to influence American politics, he took to covering Zevon’s “Lawyers, Guns and Money”. It opens with the line: “I went home with the waitress / The way I always do / How was I to know / She was with the Russians, too?” Browne clearly got a kick out of its continued relevance. “If you didn’t know that song you’d think it was written last week,” he laughs. “That song is 40 years old. It was funny then, and it’s even funnier now.”

Let the Rhythm Lead interpolates languages like Creole and Spanish, much as Zevon did on his 1982 track “The Hula Hula Boys”. When I remind Browne of this he howls with delight. “Do you know what the chorus of ‘The Hula Hula Boys’ actually means?” he asks mischievously. “It’s a saying in Hawaii that loosely means ‘get to the point’, but literally means ‘sing the chorus’. So when they sing the chorus, they’re singing ‘sing the chorus’. That is the funniest f***ing thing I have ever f***ing heard! That’s Warren Zevon at his best. With one stroke, he’s saying nothing and everything. Zevon is a singular writer.”

Now 71, after more than half a century of songwriting, Browne still believes in the power of music to change lives. He was just 16 when he wrote “These Days”, which is made all the more remarkable by the fact it contains one of the most devastating lyrics ever committed to song: “Don’t confront me with my failures/ I had not forgotten them”. Was the teenage Browne really that tortured, or was it a case of art imitating art?

“I don’t know,” he says after a pause. “I listened to a lot of old men making music when I was a kid. Blues and folk, as well as Bob Dylan, who sounded old. I was emulating them to an extent, but I wasn’t just posing as an old person. That thought resonated with me. I’ve had therapists say to me: ‘What the hell happened to you when you were young?’” He thinks he was just always an old soul. He remembers reading a book of blues lyrics his mother had given him. “There was a lyric where it arrived at the place: ‘I got so old,’” he says. “It hit me really hard. I thought: ‘F***, that’s going to happen.’ You get to a place where you can’t believe how old you are. No one ever thinks it’s gonna happen to them, isn’t that wild?”

He may be of their generation, but The Who’s line about hoping they’d die before they got old never rang true for Browne. “I’ve always disputed that inwardly,” he says. “I’ve had a problem with my back most of my life. In my thirties it got to where it was so painful I could barely lean over the sink when I brushed my teeth. I thought: ‘This is the onset of decrepitude,’ but I hadn’t tried anything! With yoga and chiropractic doctors I eradicated the problem. I remember thinking with amusement: ‘You were really ready to accept the idea that you were decrepit and there was nothing to be done about it.’ That’s maybe a metaphor for what we’re talking about, about hope in the world. Things are so bad, but I still don’t hope the world dies before it gets older.”

‘Let the Rhythm Lead: Haiti Song Summit Vol 1’ by Artists for Peace and Justice is released today (31 January)

.webp)