The first Opium war left an indelible scar on China. The mainland lost Hong Kong and was forced to open up trade to foreigners.

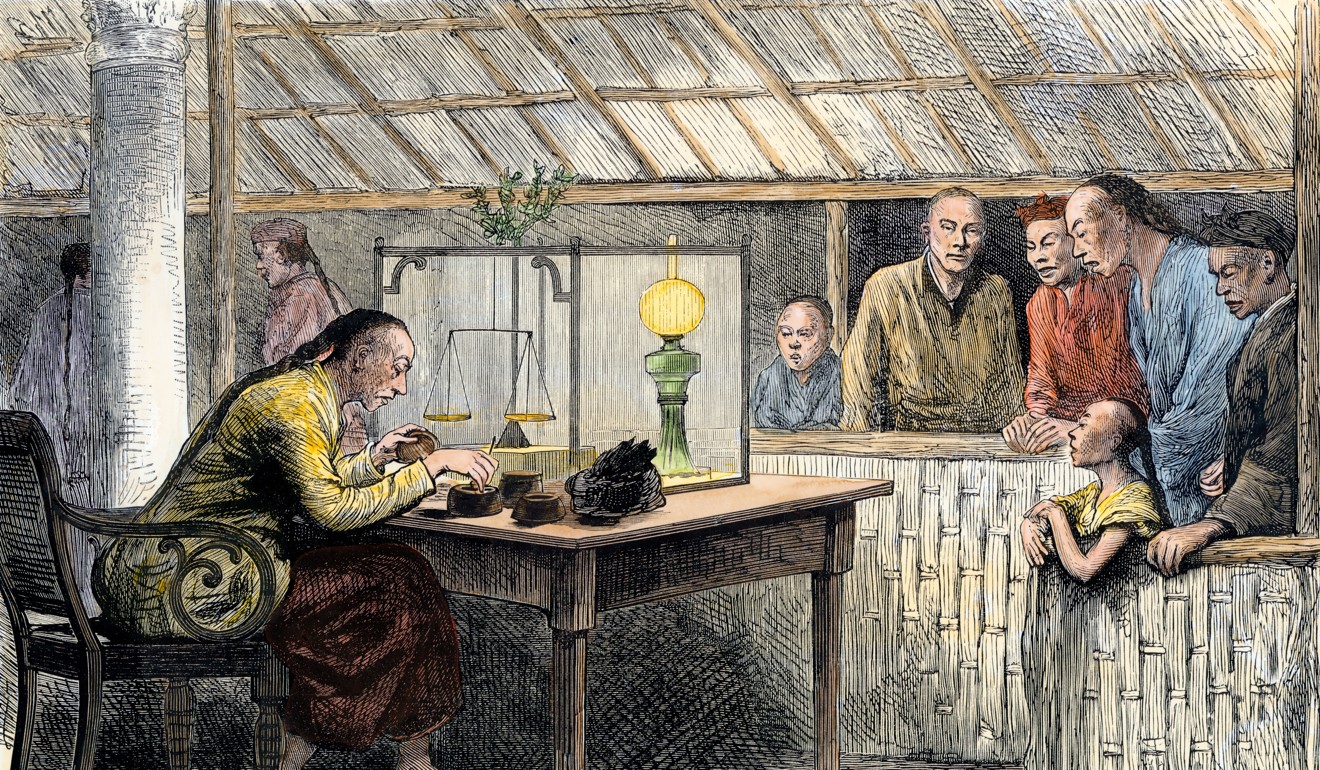

In the 18th century, foreign trade with China was limited to Canton, modern-day Guangzhou. Foreigners were confined to towns outside of Canton, known as the '13 Factories', or Hongs (not really factories). British trade was run by the East India Trading Company; Chinese trade was dominated by the Hongs.

Here is a timeline of what happened:

1820 - Import of opium begins in earnest

China is willing to provide Britain with tea and other luxury goods, but is unwilling to accept anything but silver as payment. The British have to import silver from Europe or Mexico. They run into a trade deficit and seek ways to counter-trade. They find a solution in an Indian narcotic: opium. In the next few years, the amount of opium imported to China increases dramatically. Tensions arise because, in China, opium can only be used as a medicine. It has been banned as a recreational drug for more than 100 years.

April 1839 - Lin Zexu is sent to Canton and 20,000 chests of opium are burnt

Emperor Daoguang sends government official Lin Zexu to Canton. He has already cracked down on the use of opium in Hubei and now focuses on Canton. Lin asks the British to surrender all their opium and sign an agreement to stop trading in the drug. Charles Elliot, the British superintendent of trade, agrees and promises the merchants they will be compensated by the British government. But he has no authority to sign the bond, and he wants the British to be allowed to trade along the eastern coast of China and not be confined to Canton. He threatens to stop trade until a compromise is reached. But some traders who are not dealing in opium sign the deal.

July 1839 - The Kowloon Incident

A crew of American and British sailors arrives in Kowloon in search of provisions. They get drunk on rice wine and kill a man. Lin demands that the sailors be tried in a Chinese court, citing a Swiss law that gave them jurisdiction over all foreigners. Elliot refuses and delays their sentencing, eventually giving them prison terms that were never to be met. Tensions increase.

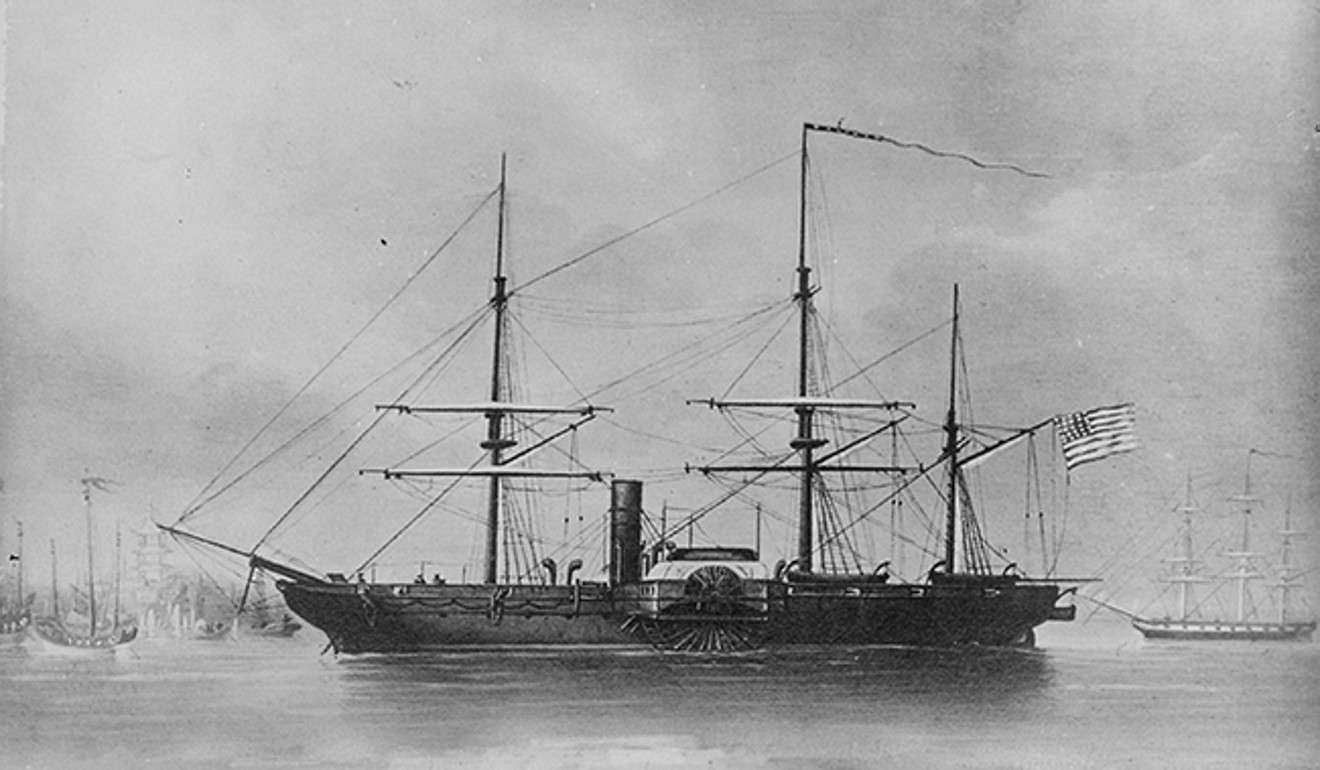

1839 - The first shots

One British merchant ship that has lost faith in Elliot ignores the ban. Elliot blockades the Pearl River. A second ship tries to run the blockade. British ships chase after it and fire the first shots of what will become the Opium war. The Chinese navy tries to protect the merchant ship, which is not trading in opium, and a battle ensues. The Chinese suffer many losses; the British only one injury. This is the first battle of Chuenpee.

April 1840 - Motion to go to war passed

The British government, after much delay and debate, narrowly passes a motion for war against China. The war is funded by the government and seeks to force China to open up trade along the eastern coast.

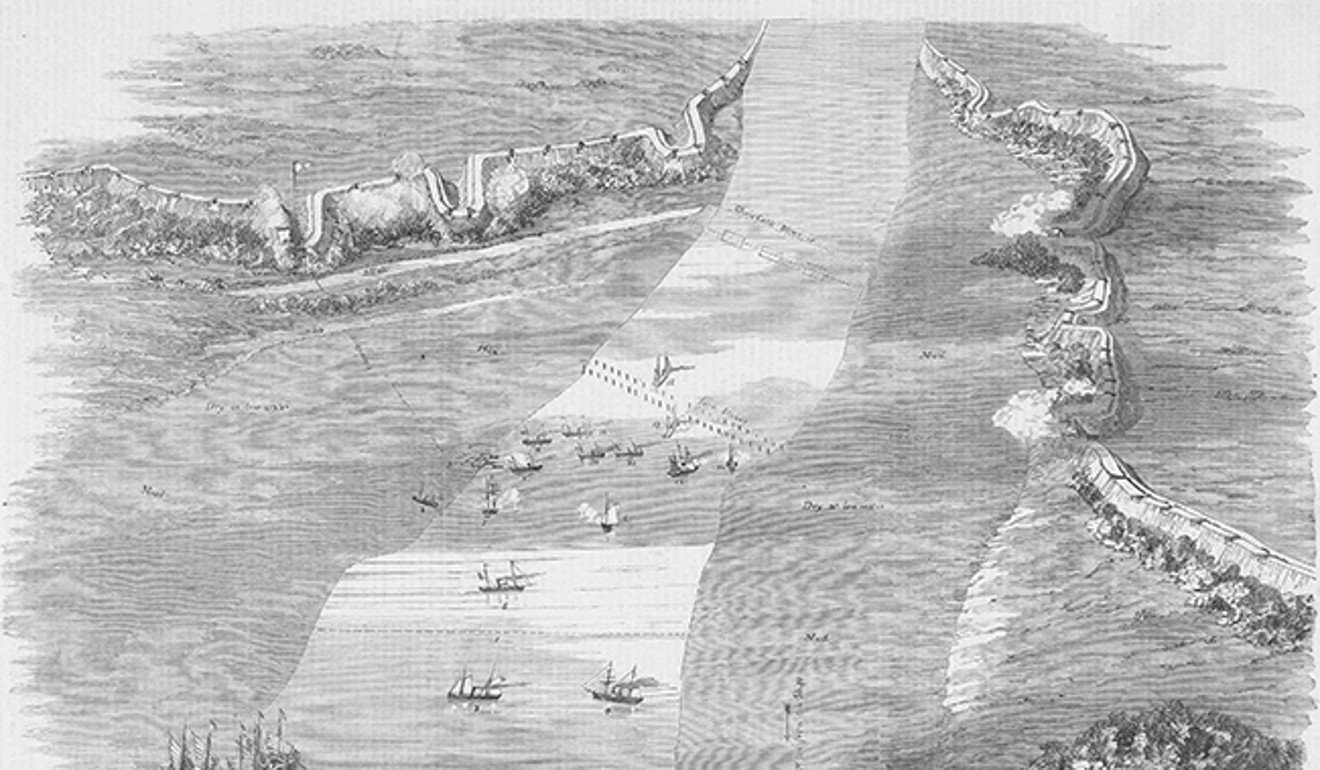

Summer 1840 - The occupation of Zhoushan and first talks of Hong Kong's cession

British forces gather off the coast of Macau with Elliot and his cousin, George Elliot, in charge. The British occupy Zhoushan and its principal town Dinghai, fighting almost unopposed. Meanwhile, Lin has fallen from the emperor's favour.

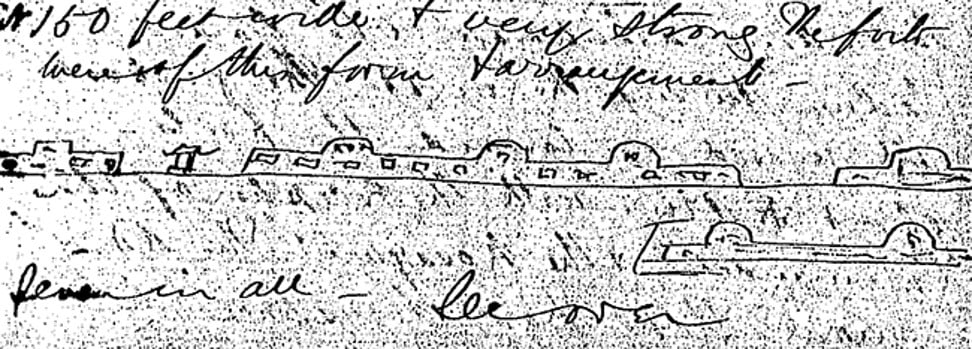

January 1841 - Negotiations

Second battle of Cheunpee happens on January 17. Lin has been replaced with Imperial Commissioner Qishan who is eager to negotiate with the British. Elliot asks for seven million dollars over six years and several inland ports. Qishan agrees to give the British six million over 12 years, but rejects the possibility of inland ports. The British prepare for battle and Qishan reconsiders. They finally agree to the Treaty of Chuanbi which cedes Hong Kong Island and six million dollars to the British. This treaty is rejected by both governments. Fighting resumes along the eastern shore.

Summer 1842 - The Treaty of Nanking

British forces beat the Chinese right up to the Yangtze, and occupy Shanghai. The Chinese suffer many casualties and are forced to surrender. On August 29, the Treaty of Nanking is signed, five ports (Canton, Ziamen, Fuzhou, Ningbo and Shanghai) are opened and Hong Kong is ceded to the British.