Nora Krug: Replacing German 'guilt' with 'responsibility' to defend democracy

Nora Krug is the author of a bestselling graphic memoir titled "Heimat," which looks into her family's involvement in World War II. DW asked her what we can learn from the generation of "followers" of the Nazi Party

"Heimat" is a loaded German term; it was misappropriated by the Nazis and more recently by the far right. Edgar Reitz, the director of a series of films in the 1980s called "Heimat," told DW in an interview that he wouldn't have called his project that way today; he finds the term to difficult to defend. Why did you pick it for your book?

That's exactly why we decided to call the book "Heimat," because we felt that we needed to claim the term back from the extreme right. The book is both a quest to find out what it means to be German and it's also a commitment to Germany — in a positive sense. I believe it should be possible to both look critically at our past and express love for our country

Your graphic memoir offers a complex, very poetic interpretation of the concept of Heimat. But did you also come up with an easy way to define the term in interviews?

I don't think I have a clear definition of the word Heimat yet. The goal of the book wasn't to provide easy answers or to understand what being German means, but more an attempt to better understand the German war experience.

And even after the whole process of writing the book, I can't really say that I know what the term Heimat means to me personally, partly because I've been living abroad for all in all 20 years. And it's also a term that changes over time, just as we change and our society changes. And that's how it should be looked at, as something that's not static but that's allowed to change and mean different things to different individuals.

Did you initially conceive your book for Germans or for English-language readers?

When I first wrote the book, I really had an American audience in mind because, as a German living among non-Germans in America, I had been often confronted with negative stereotypes about Germans, but also with a lack of knowledge of what we do with the legacy of the war. So that's why I wrote the book in English first.

And then I realized that the German publishing world was actually the one that was the most excited about it, because living with this legacy is still such a trauma for the Germans as well.

Read more: 'Maus' cartoonist Art Spiegelman turns 70

Your book details your quest to find out more about your ancestors' involvement in the war; would you encourage other Germans to do that research too?

Everybody has their own way of dealing with the past, so I wouldn't say that there's one way of handling it. But I personally think it's always better to know than not to know. I found it difficult to live with gaps in my family narrative. I wanted to ask as many questions as I could, and find out as much as possible. And now we have so many technological possibilities to find information that wasn't available maybe 15 years ago; certain files have only been made public recently.

We now understand how people ended up joining the Nazi party without having committed war crimes, so it's something we'd expect to see in most families. Still, you describe the moment you found out that one of your relatives was officially categorized as a "follower" in the denazification as very emotional. Why did it hurt so much?

I had always suspected that nobody in my family had been a major Nazi, because I think that's the kind of information that you can't keep hidden; it would have come up much earlier in my life.

But I grew up with this narrative of my grandfather Willi as somebody who had voted for the Social Democrats all his life, who were the Nazis' major political enemies. So there had always been this myth of him having nothing to do at all with the Nazi regime. So when I found out at the archive that he had actually been a member of the Nazi party, at a time when it was actually not so easy to join, I was very surprised and it was painful, because I saw myself confronted with a side of him that was uncomfortable to witness — of somebody who was opportunistic in his choices, and a bit of a coward.

A picture in the book "Heimat": Nora with her now deceased grandfather

Your ancestors' ambiguous position during the war — they weren't Nazi criminals but they weren't engaged in the Resistance either — not only reflects the case of a majority of Germans, it also makes your book more universal, since we end up thinking, "that could have been my family," or even in a way, "that is me today…" Was this one of your goals in making the book?

Yeah, exactly. I think that the gray zone of the war, those people who fall in between the categories of Resistance fighters, victims, and major Nazis or war criminals, is the category that is the most important to look at, because it is probably the one that most of us would identify with, and the one that probably teaches us most about how dictatorial regimes work.

That group of people has been overlooked a bit in German society, because it's easy to say "well everybody was a follower and my family was among those people who followed." But I think that's just too easy; the term follower is so much wider. There were followers who saved Jewish lives for instance. And then there were followers who committed terrible crimes. So that's why I feel it's so important to look at individual narratives and try to deconstruct individual myths that maybe circulate in your family.

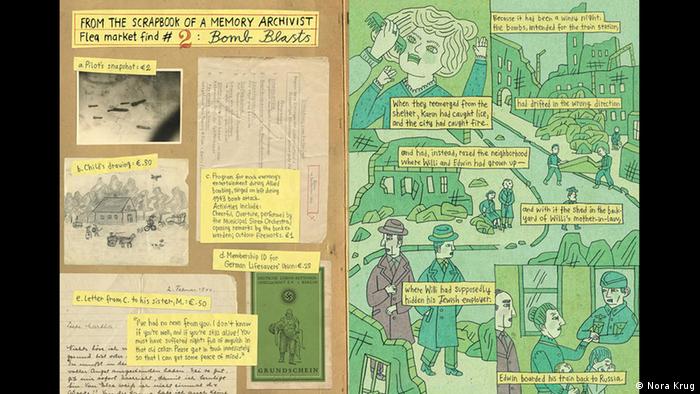

A page from Nora Krug's book

Many Germans claimed they didn't realize what was happening under Hitler. Today we are very well informed of the world's problems, and we are witnessing events in the US that are often compared to Germany in the 1930s. As a naturalized US citizen with a German background, what is your reaction to the current political situation there?

What's going on in the US at the moment is very frightening. And I do think there are parallels in some of the behavior we are witnessing, such as how language has become much more aggressive, which is of course troubling. I'm actually reading Mein Kampf at the moment for the first time in my life, and it's so evident that language is the seed of violence. But I do think that the comparison between Hitler and Trump is too easy to make from a historical point of view, even if some traits of personality are familiar.

And does the election of far-right politicians in Germany scare you more?

I think it's equally scary. As a German, I'm of course very concerned about the developments in Germany. One of the things I find the most concerning is the fact that society is so split today and that it's becoming increasingly difficult to talk to one another, to have a civilized dialogue. I think Germany underestimated what had been going on under the surface for a long time. Now we need to really take it very seriously.

And what is your role as an artist in this context?

One of the most important goals of my book was to give a universal quality to the story, so that it wouldn't only apply to Germany and the Nazi regime and allow readers to project the situation back then to what's happening now, and maybe find ways of replacing the term "guilt" with "responsibility" and think about what we can do today to contribute to a tolerant society and defend our democracy. I used to think that democracy was basically as a state of being. But I realize now that it's a process that's that we constantly need to defend.

GO HERE TO WATCH VIDEOhttps://www.dw.com/en/nora-krug-replacing-german-guilt-with-responsibility-to-defend-democracy/a-49960409

GO HERE TO WATCH VIDEOhttps://www.dw.com/en/nora-krug-replacing-german-guilt-with-responsibility-to-defend-democracy/a-49960409