Stress and physical strain also has led to 16 deaths so far this year from overwork,

known as gwarosa in Korea

"We need to work to live. It's ironic that people are dying from it."

By Thomas Maresca

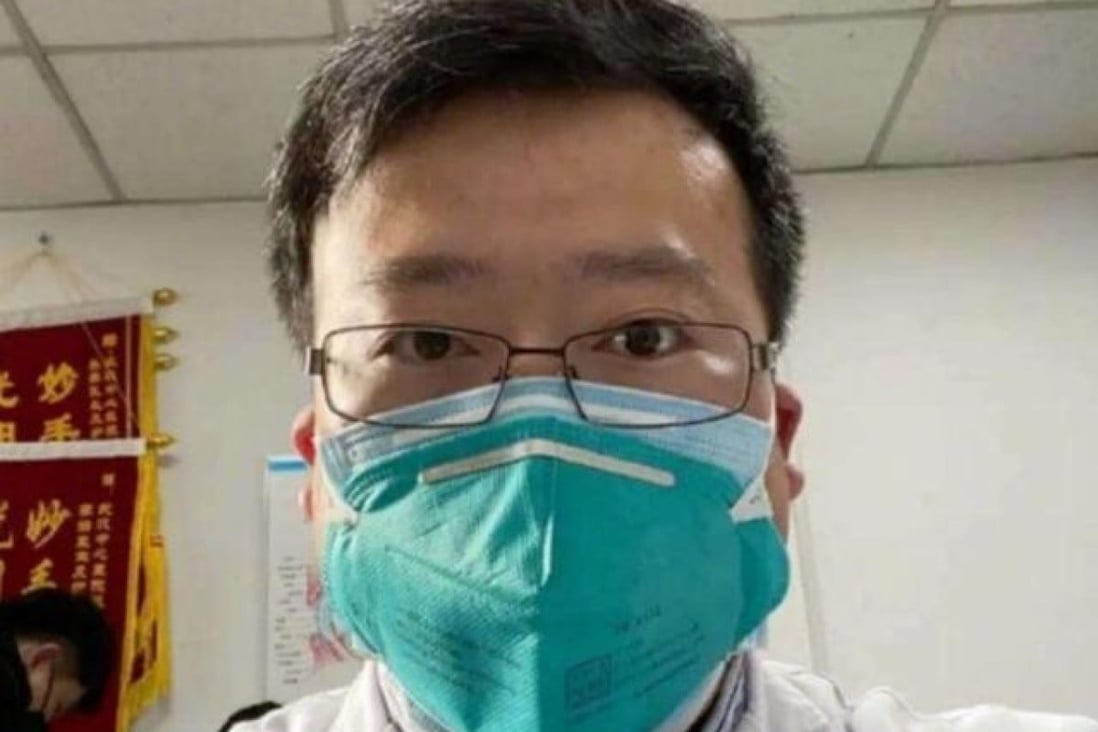

Kim Do-gyun is one of the more than 50,000 delivery drivers working grueling hours as shipments skyrocket during the COVID-19 pandemic. Photo by Thomas Maresca/UPI

SEOUL, Dec. 24 (UPI) -- While the COVID-19 pandemic has taken an economic toll on many industries, online shopping and delivery services have thrived in this year of shuttered storefronts and social distancing.

In South Korea, however, the delivery drivers at the heart of the pandemic economy say that the boom has left them working brutal hours, with an alarming number of injuries and even deaths on the job.

"This year has been very tough," delivery worker Kim Do-gyun, 48, said as he made deliveries on his route northeast of Seoul on Christmas Eve. "There's no other sector where so many workers have died. It's a serious systematic problem."

Couriers have been logging an average of over 71 hours per week during the COVID-19 era, according to a September survey by the Center for Workers' Health and Safety -- an increase of 30% over pre-virus days.

Stress and physical strain also has led to 16 deaths so far this year from overwork, known as gwarosa in Korean, a union for the drivers says.

The most recent death came this week, when a 34-year-old delivery worker in the city of Suwon was found dead Wednesday at his home. The worker, identified as Mr. Park by the union, had routinely worked from 6 a.m. until 9 p.m. and had lost more than 40 pounds since July, according to family members.

Long days such as these have become the norm for the more than 50,000 delivery workers in South Korea such as Kim, who has been a driver for six years.

Kim said he wakes up at 5:30 a.m. to get to the distribution has center where he starts his day before 7 a.m. There, like most couriers, he spends the next several hours sorting his packages as they come tumbling down a conveyor belt -- work that is unpaid, as drivers only receive a commission for each parcel they deliver.

He usually finishes sorting between 1:30 and 2 p.m. before finally beginning his deliveries, which he wraps up each night at 9 or 10 p.m. Kim carries out the routine six days a week, often skipping meals and subsisting on snacks in the cab of his truck.

Profits have soared for South Korea's delivery giants, such as CJ Logistics, Hanshin Shipping and Lotte Global Logistics, on the back of shipments that have grown more than 20% this year, but the benefits have not been trickling down to the drivers.

Kim Do-gyun is one of the more than 50,000 delivery drivers working grueling hours as shipments skyrocket during the COVID-19 pandemic. Photo by Thomas Maresca/UPI

SEOUL, Dec. 24 (UPI) -- While the COVID-19 pandemic has taken an economic toll on many industries, online shopping and delivery services have thrived in this year of shuttered storefronts and social distancing.

In South Korea, however, the delivery drivers at the heart of the pandemic economy say that the boom has left them working brutal hours, with an alarming number of injuries and even deaths on the job.

"This year has been very tough," delivery worker Kim Do-gyun, 48, said as he made deliveries on his route northeast of Seoul on Christmas Eve. "There's no other sector where so many workers have died. It's a serious systematic problem."

Couriers have been logging an average of over 71 hours per week during the COVID-19 era, according to a September survey by the Center for Workers' Health and Safety -- an increase of 30% over pre-virus days.

Stress and physical strain also has led to 16 deaths so far this year from overwork, known as gwarosa in Korean, a union for the drivers says.

The most recent death came this week, when a 34-year-old delivery worker in the city of Suwon was found dead Wednesday at his home. The worker, identified as Mr. Park by the union, had routinely worked from 6 a.m. until 9 p.m. and had lost more than 40 pounds since July, according to family members.

Long days such as these have become the norm for the more than 50,000 delivery workers in South Korea such as Kim, who has been a driver for six years.

Kim said he wakes up at 5:30 a.m. to get to the distribution has center where he starts his day before 7 a.m. There, like most couriers, he spends the next several hours sorting his packages as they come tumbling down a conveyor belt -- work that is unpaid, as drivers only receive a commission for each parcel they deliver.

He usually finishes sorting between 1:30 and 2 p.m. before finally beginning his deliveries, which he wraps up each night at 9 or 10 p.m. Kim carries out the routine six days a week, often skipping meals and subsisting on snacks in the cab of his truck.

Profits have soared for South Korea's delivery giants, such as CJ Logistics, Hanshin Shipping and Lotte Global Logistics, on the back of shipments that have grown more than 20% this year, but the benefits have not been trickling down to the drivers.

Only a tiny fraction of the couriers work for the major shipping companies directly; the rest are contract laborers for agencies that act as intermediaries. As such, they remain in a legal limbo without worker protections such as a 52-hour maximum workweek introduced by President Moon Jae-in in 2018.

"The reason why they are working under conditions like this is because the companies do not hire them directly -- they are classified as special workers and do not fall under the Labor Standards Act," said Kang Min-wook, head of training and publicity for the National Association of Delivery Drivers, the union that supports the couriers.

"The companies don't pay them hourly, and they are not protected by the law. So the [courier] companies are making more money, but the workers are not seeing the same benefits," he said.

Delivery drivers are paid by the parcel, a commission that has been squeezed this year by competition between the big courier companies, Kang said. It currently stands at around 65 cents per package.

The couriers have seen their sheer volume of packages delivered rise dramatically this year, according to the September survey. Before the pandemic, an average daily total of deliveries for a driver was 247. This year, it's been 313. On Christmas Eve, Kim had 352 parcels to deliver.

However, drivers face a host of expenses that eat into their earnings. They must supply and maintain their own delivery trucks, as well as pay for everything from packing tape to waybills to the specialized delivery app they use. The couriers also don't receive any paid time off, and most are not covered by accident insurance.

As South Korea dipped into a recession in the first half of the year due to the pandemic and is currently trying to recover from a third wave of the virus, gig workers such as couriers find themselves without many alternatives for employment.

"Most delivery workers used to work in another sector, but now we have nowhere else to go," Kim said. "We're at the end of the road."

Protests, strikes and news coverage has heightened awareness of the plight of the delivery drivers, and the public has responded with social media campaigns and gestures such as leaving thank-you notes and snacks for the couriers.

The government has also begun taking steps to improve the situation, passing legislation earlier this month that will offer unemployment benefits and accident insurance to gig workers beginning later in 2021.

This week, the Ministry of Employment and Labor announced that it would set up a dedicated department for gig workers and more closely regulate delivery companies.

"Currently, anyone can establish a delivery service without restrictions, which limits the protection of delivery workers," Employment and Labor Minister Lee Jae-kap said during a press briefing Monday.

The shipping companies have announced a series of changes, including adopting flexible hours and adding manpower. CJ Logistics, the largest firm in the industry with some 21,000 workers, announced in October it would hire 4,000 more employees to help sort packages.

Kim, however, said he hasn't seen any difference yet in his daily routine.

"The companies have announced the solutions and they say they will take place, but I question whether they'll really happen," said Kim, who is active in the driver's labor union.

"I don't have any hope that things will change unless we fight," he said. "Because if we don't fight against this, nothing will change. Nothing will improve."

In the meantime, Kim said he fully expects there to be more injuries and more cases of gwarosa in the days and weeks ahead.

"I believe there will be more deaths," he said.

"We need to work to live. It's ironic that people are dying from it."

Seo Jieun contributed

Seo Jieun contributed