By SAMYA KULLAB

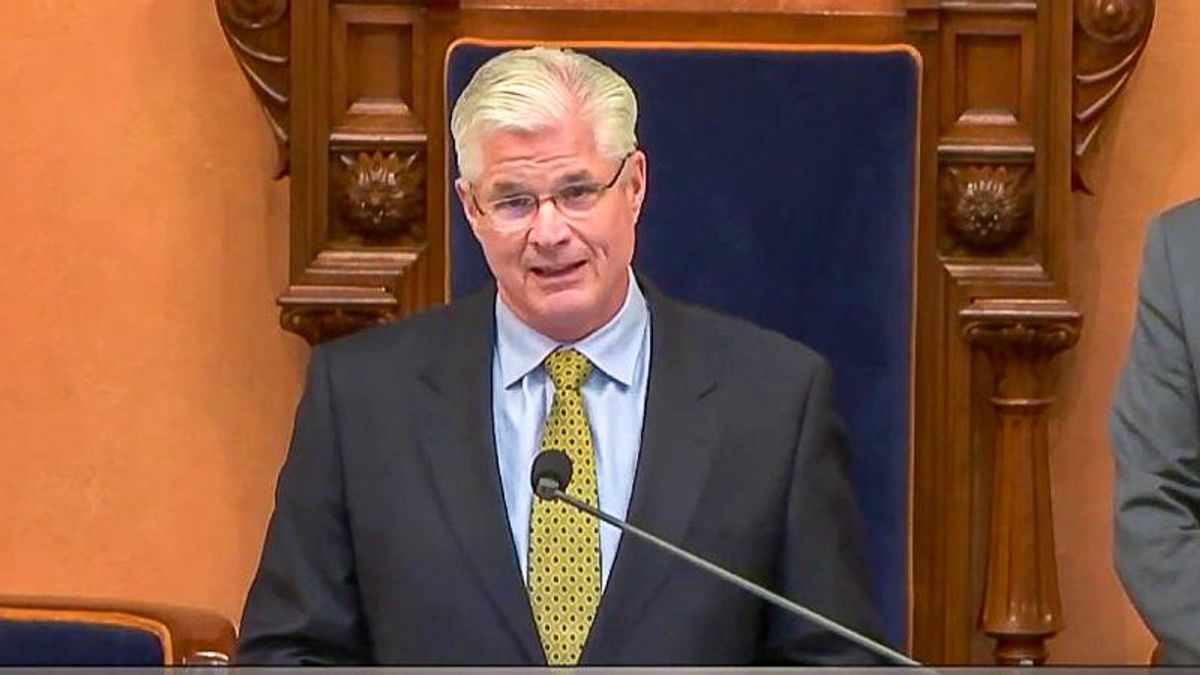

Ayat Rawthan, a petrochemical engineer, poses for a photo near an oil field outside Basra, Iraq, Tuesday, Feb. 5, 2021. Rawthan is among just a handful of women who have eschewed the dreary office jobs typically handed to female petrochemical engineers in Iraq. Instead, they chose to become trailblazers in the country’s oil industry, taking up the grueling work of drilling. (AP Photo/Nabil al-Jourani)

BASRA, Iraq (AP) — It’s nearly dawn and Zainab Amjad has been up all night working on an oil rig in southern Iraq. She lowers a sensor into the black depths of a well until sonar waves detect the presence of the crude that fuels her country’s economy.

Elsewhere in the oil-rich province of Basra, Ayat Rawthan is supervising the assembly of large drill pipes. These will bore into the Earth and send crucial data on rock formations to screens sitting a few meters (feet) away that she will decipher.

The women, both 24, are among just a handful who have eschewed the dreary office jobs typically handed to female petroleum engineers in Iraq. Instead, they chose to become trailblazers in the country’s oil industry, donning hard hats to take up the grueling work at rig sites.

They are part of a new generation of talented Iraqi women who are testing the limits imposed by their conservative communities. Their determination to find jobs in a historically male-dominated industry is a striking example of the way a burgeoning youth population finds itself increasingly at odds with deeply entrenched and conservative tribal traditions prevalent in Iraq’s southern oil heartland.

The hours Amjad and Rawthan spend in the oil fields are long and the weather unforgiving. Often they are asked what — as women — they are doing there.

“They tell me the field environment only men can withstand,” said Amjad, who spends six weeks at a time living at the rig site. “If I gave up, I’d prove them right.”

Iraq’s fortunes, both economic and political, tend to ebb and flow with oil markets. Oil sales make up 90% of state revenues — and the vast majority of the crude comes from the south. A price crash brings about an economic crisis; a boom stuffs state coffers. A healthy economy brings a measure of stability, while instability has often undermined the strength of the oil sector. Decades of wars, civil unrest and invasion have stalled production.

Following low oil prices dragged down by the coronavirus pandemic and international disputes, Iraq is showing signs of recovery, with January exports reaching 2.868 million barrels per day at $53 per barrel, according to Oil Ministry statistics.

To most Iraqis, the industry can be summed up by those figures, but Amjad and Rawthan have a more granular view. Every well presents a set of challenges; some required more pressure to pump, others were laden with poisonous gas. “Every field feels like going to a new country,” said Amjad.

Given the industry’s outsized importance to the economy, petrochemical programs in the country’s engineering schools are reserved for students with the highest marks. Both women were in the top 5% of their graduating class at Basra University in 2018.

In school they became awestruck by drilling. To them it was a new world, with it’s own language: “spudding” was to start drilling operations, a “Christmas tree” was the very top of a wellhead, and “dope” just meant grease.

Every work day plunges them deep into the mysterious affairs below the Earth’s crust, where they use tools to look at formations of minerals and mud, until the precious oil is found. “Like throwing a rock into water and studying the ripples,” explained Rawthan.

To work in the field, Amjad, the daughter of two doctors, knew she had to land a job with an international oil company — and to do that, she would have to stand out. State-run enterprises were a dead end; there, she would be relegated to office work.

“In my free time, on my vacations, days off I was booking trainings, signing up for any program I could,” said Amjad.

When China’s CPECC came to look for new hires, she was the obvious choice. Later, when Texas-based Schlumberger sought wireline engineers she jumped at the chance. The job requires her to determine how much oil is recoverable from a given well. She passed one difficult exam after another to get to the final interview.

Asked if she was certain she could do the job, she said: “Hire me, watch.”

In two months she traded her green hard hat for a shiny white one, signifying her status as supervisor, no longer a trainee — a month quicker than is typical.

Rawthan, too, knew she would have to work extra hard to succeed. Once, when her team had to perform a rare “sidetrack” — drilling another bore next to the original — she stayed awake all night.

“I didn’t sleep for 24 hours, I wanted to understand the whole process, all the tools, from beginning to end,” she said.

Rawthan also now works for Schlumberger, where she collects data from wells used to determine the drilling path later on. She wants to master drilling, and the company is a global leader in the service.

Relatives, friends and even teachers were discouraging: What about the hard physical work? The scorching Basra heat? Living at the rig site for months at a time? And the desert scorpions that roam the reservoirs at night?

“Many times my professors and peers laughed, ‘Sure, we’ll see you out there,’ telling me I wouldn’t be able to make it,” said Rawthan. “But this only pushed me harder.”

Their parents were supportive, though. Rawthan’s mother is a civil engineer and her father, the captain of an oil tanker who often spent months at sea.

“They understand why this is my passion,” she said. She hopes to help establish a union to bring like-minded Iraqi female engineers together. For now, none exists.

The work is not without danger. Protests outside oil fields led by angry local tribes and the unemployed can disrupt work and sometimes escalate into violence toward oil workers. Confronted every day by flare stacks that point to Iraq’s obvious oil wealth, others decry state corruption, poor service delivery and joblessness.

But the women are willing to take on these hardships. Amjad barely has time to even consider them: It was 11 p.m., and she was needed back at work.

“Drilling never stops,” she said.