By Adam Mann

3 days ago

How many bits does the universe contain? A lot.

How many bits does the universe contain? A lot.

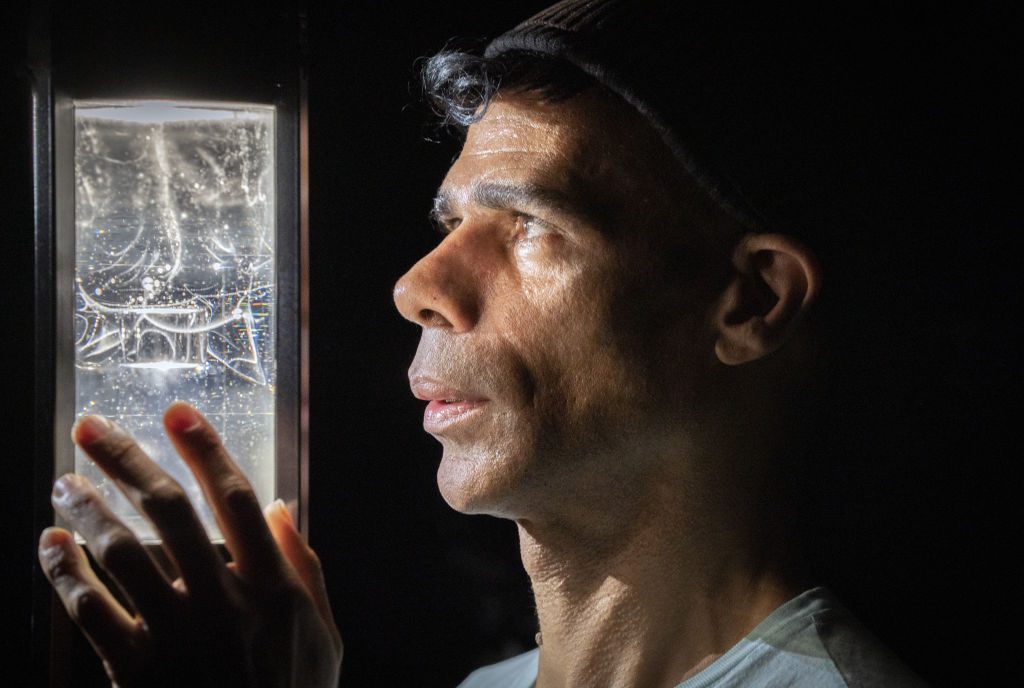

(Image credit: Yuichiro Chino via Getty Images)

The visible cosmos may contain roughly 6 x 10^80 — or 600 million trillion trillion trillion trillion trillion trillion — bits of information, according to a new estimate.

The findings could have implications for the speculative possibility that the universe is actually a gigantic computer simulation.

Underlying the mind-boggling number is an even stranger hypothesis. Six decades ago, German-American physicist Rolf Landauer proposed a type of equivalence between information and energy, since erasing a digital bit in a computer produces a tiny amount of heat, which is a form of energy.

Because of Albert Einstein's famous equation E = mc^2, which says that energy and matter are different forms of one another, Melvin Vopson, a physicist at the University of Portsmouth in England, previously conjectured that a relationship might exist between information, energy and mass.

"Using the mass-energy-information equivalence principle, I speculated that information could be a dominant form of matter in the universe," he told Live Science. Information might even account for dark matter, the mysterious substance that makes up the vast majority of matter in the cosmos, he added.

Vopson set out to determine the amount of information in a single subatomic particle, such as a proton or neutron. Such entities can be fully described by three basic characteristics: their mass, charge and spin, he said.

"These properties make elementary particles distinguishable [from] each other, and they could be regarded as 'information,'" he added.

Information has a specific definition first given by American mathematician and engineer Claude Shannon in a groundbreaking 1948 paper called "A Mathematical Theory of Communication." By looking at the maximum efficiency at which information could be transmitted, Shannon introduced the concept of the bit. This can have a value of either 0 or 1, and is used to measure units of information, much like distance is measured in feet or meters or temperature is measured in degrees, Vopson said.

Using Shannon's equations, Vopson calculated that a proton or neutron should contain the equivalent of 1.509 bits of encoded information. Vopson then derived an estimate for the total number of particles in the observable universe — around 10^80, which accords with previous estimates — to determine the total information content of the cosmos. His findings appeared Oct. 19 in the journal AIP Advances.

Even though the resulting number is enormous, it still isn't large enough to account for the dark matter in the universe, Vopson said. In his earlier work, he estimated that approximately 10^93 bits of information — a number 10 trillion times larger than the one he derived — would be necessary to do so.

"The number I calculated is smaller than I expected," he said, adding that he is unsure why. It could be that important things were unaccounted for in his calculations, which focused on particles like protons and neutrons but ignored entities like electrons, neutrinos and quarks, because, according to Vopson, only protons and neutrons can store information about themselves.

He admits that it’s possible that the assumption is wrong and perhaps other particles can store information about themselves as well.

This may be why his results are so different from prior calculations of the universe's total information, which tend to be much higher, said Greg Laughlin, an astronomer at Yale University who wasn't involved in the work.

"It's sort of ignoring not the elephant in the room, but the 10 billion elephants in the room," Laughlin told Live Science, referring to the many particles not considered in the new estimate.

While such calculations may not have immediate applications, they could be of use to those who speculate that the visible cosmos is, in reality, a gigantic computer simulation, Laughlin said. This so-called simulation hypothesis is "a really fascinating idea," he said.

"Calculating the information content — basically the number of bits of memory that would be required to run [the universe] — is interesting," he added.

But, as of yet, the simulation hypothesis remains a mere hypothesis. "There's no way to know whether that's true," Laughlin said.

Originally published on Live Science.

The visible cosmos may contain roughly 6 x 10^80 — or 600 million trillion trillion trillion trillion trillion trillion — bits of information, according to a new estimate.

The findings could have implications for the speculative possibility that the universe is actually a gigantic computer simulation.

Underlying the mind-boggling number is an even stranger hypothesis. Six decades ago, German-American physicist Rolf Landauer proposed a type of equivalence between information and energy, since erasing a digital bit in a computer produces a tiny amount of heat, which is a form of energy.

Because of Albert Einstein's famous equation E = mc^2, which says that energy and matter are different forms of one another, Melvin Vopson, a physicist at the University of Portsmouth in England, previously conjectured that a relationship might exist between information, energy and mass.

"Using the mass-energy-information equivalence principle, I speculated that information could be a dominant form of matter in the universe," he told Live Science. Information might even account for dark matter, the mysterious substance that makes up the vast majority of matter in the cosmos, he added.

Vopson set out to determine the amount of information in a single subatomic particle, such as a proton or neutron. Such entities can be fully described by three basic characteristics: their mass, charge and spin, he said.

"These properties make elementary particles distinguishable [from] each other, and they could be regarded as 'information,'" he added.

Information has a specific definition first given by American mathematician and engineer Claude Shannon in a groundbreaking 1948 paper called "A Mathematical Theory of Communication." By looking at the maximum efficiency at which information could be transmitted, Shannon introduced the concept of the bit. This can have a value of either 0 or 1, and is used to measure units of information, much like distance is measured in feet or meters or temperature is measured in degrees, Vopson said.

Using Shannon's equations, Vopson calculated that a proton or neutron should contain the equivalent of 1.509 bits of encoded information. Vopson then derived an estimate for the total number of particles in the observable universe — around 10^80, which accords with previous estimates — to determine the total information content of the cosmos. His findings appeared Oct. 19 in the journal AIP Advances.

Even though the resulting number is enormous, it still isn't large enough to account for the dark matter in the universe, Vopson said. In his earlier work, he estimated that approximately 10^93 bits of information — a number 10 trillion times larger than the one he derived — would be necessary to do so.

"The number I calculated is smaller than I expected," he said, adding that he is unsure why. It could be that important things were unaccounted for in his calculations, which focused on particles like protons and neutrons but ignored entities like electrons, neutrinos and quarks, because, according to Vopson, only protons and neutrons can store information about themselves.

He admits that it’s possible that the assumption is wrong and perhaps other particles can store information about themselves as well.

This may be why his results are so different from prior calculations of the universe's total information, which tend to be much higher, said Greg Laughlin, an astronomer at Yale University who wasn't involved in the work.

"It's sort of ignoring not the elephant in the room, but the 10 billion elephants in the room," Laughlin told Live Science, referring to the many particles not considered in the new estimate.

While such calculations may not have immediate applications, they could be of use to those who speculate that the visible cosmos is, in reality, a gigantic computer simulation, Laughlin said. This so-called simulation hypothesis is "a really fascinating idea," he said.

"Calculating the information content — basically the number of bits of memory that would be required to run [the universe] — is interesting," he added.

But, as of yet, the simulation hypothesis remains a mere hypothesis. "There's no way to know whether that's true," Laughlin said.

Originally published on Live Science.

:format(jpeg)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/tgam/5AKRNJGSVFJDPNNUBCHIUJBS3Y.jpg)