Published: March 20, 2022

In early 2022, nearly two years after Covid was declared a pandemic by the World Health Organization, experts are mulling a big question: when is a pandemic “over”?

So, what’s the answer? What criteria should be used to determine the “end” of Covid’s pandemic phase? These are deceptively simple questions and there are no easy answers.

I am a computer scientist who investigates the development of ontologies. In computing, ontologies are a means to formally structure knowledge of a subject domain, with its entities, relations and constraints, so that a computer can process it in various applications and help humans to be more precise.

Ontologies can discover knowledge that’s been overlooked until now: in one instance, an ontology identified two additional functional domains in phosphatases (a group of enzymes) and a novel domain architecture of a part of the enzyme. Ontologies also underlie Google’s Knowledge Graph that’s behind those knowledge panels on the right-hand side of a search result.

Join thousands of Canadians who subscribe to free evidence-based news.Get newsletter

Applying ontologies to the questions I posed at the start is useful. This approach helps to clarify why it is difficult to specify a cut-off point at which a pandemic can be declared “over”. The process involves collecting definitions and characterisations from domain experts, like epidemiologists and infectious disease scientists, consulting relevant research and other ontologies and investigating the nature of what entity “X” is.

“X”, here, would be the pandemic itself – not a mere shorthand definition, but looking into the properties of that entity. Such a precise characterisation of the “X” will also reveal when an entity is “not an X”. For instance, if X = house, a property of houses is that they all must have a roof; if some object doesn’t have a roof, it definitely isn’t a house.

With those characteristics in hand, a precise, formal specification can be formulated, aided by additional methods and tools. From that, the what or when of “X” – the pandemic is over or it is not – would logically follow. If it doesn’t, at least it will be possible to explain why things are not that straightforward.

This sort of precision complements health experts’ efforts, helping humans to be more precise and communicate more precisely. It forces us to make implicit assumptions explicit and clarifies where disagreements may be.

Definitions and diagrams

I conducted an ontological analysis of “pandemic”. First, I needed to find definitions of a pandemic.

Informally, an epidemic is an occurrence during which there are multiple instances of an infectious disease in organisms, for a limited duration of time, that affects a community of said organisms living in some region. A pandemic, as a minimum, extends the region where the infections take place.

Read more: When will the COVID-19 pandemic end? 4 essential reads on past pandemics and what the future could bring

Next, I drew from an existing foundational ontologies. This contains generic categories like “object”, “process”, and “quality”. I also used domain ontologies, which contain entities specific to a subject domain, like infectious diseases. Among other resources, I consulted the Infectious Disease Ontology and the Descriptive Ontology for Linguistic and Cognitive Engineering.

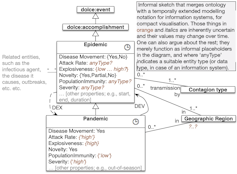

First, I aligned “pandemic” to a foundational ontology, using a decision diagram to simplify the process. This helped to work out what kind of thing and generic category “pandemic” is:

(1) Is [pandemic] something that is happening or occurring? Yes (perdurant, i.e., something that unfolds in time, rather than be wholly present).

(2) Are you able to be present or participate in [a pandemic]? Yes (event).

(3) Is [a pandemic] atomic, i.e., has no subdivisions and has a definite end point? No (accomplishment).

The word “accomplishment” may seem strange here. But, in this context, it makes clear that a pandemic is a temporal entity with a limited lifespan and will evolve – that is, cease to be a pandemic and evolve back to epidemic, as indicated in this diagram.

Characteristics

Next, I examined a pandemic’s characteristics described in the literature. A comprehensive list is described in a paper by US infectious disease specialists published in 2009 during the global H1N1 influenza virus outbreak. They collated eight characteristics of a pandemic.

Read more: New COVID data: South Africa has arrived at the recovery stage of the pandemic

I listed them and assessed them from an ontological perspective:

Wide geographic extension. This is an imprecise feature – be it fuzzy in the mathematical sense or estimated by other means: there isn’t a crisp threshold when “wide” starts or ends.

Disease movement: there’s transmission from place to place and that can be traced. A yes/no characteristic, but it could be made categorical or with ranges of how slowly or fast it moves.

High attack rates and explosiveness, or: many people are affected in a short timespan. Many, short, fast – all indicate imprecision.

Minimal population immunity: immunity is relative. You have it to a degree to some or all of the variants of the infectious agent, and likewise for the population. This is an inherently fuzzy feature.

Novelty: A yes/no feature, but one could add “partial”.

Infectiousness: it must be infectious (excluding non-infectious things, like obesity), so a clear yes/no.

Contagiousness: this may be from person to person or through some other medium. This property includes human-to-human, human-animal intermediary (e.g., fleas, rats), and human-environment (notably: water, as with cholera), and their attendant aspects.

Severity: Historically, the term “pandemic” has been applied more often for severe diseases or those with high fatality rates (e.g., HIV/AIDS) than for milder ones. This has some subjectivity, and thus may be fuzzy.

Properties with imprecise boundaries annoy epidemiologists because they may lead to different outcomes of their prediction models. But from my ontologist’s viewpoint, we’re getting somewhere with these properties. From the computational side, automated reasoning with fuzzy features is possible.

COVID, at least early in 2020, easily ticked all eight boxes. A suitably automated reasoner would have classified that situation as a pandemic. But now, in early 2022? Severity (point 8) has largely decreased and immunity (point 4) has risen. Point 5 – are there worse variants of concern to come – is the million-dollar question. More ontological analysis is needed.

Highlighting the difficulties

Ontologically speaking, then, a pandemic is an event (“accomplishment”) that unfolds in time. To be classified as a pandemic, there are a number of features that aren’t all crisp and for which the imprecise boundaries haven’t all been set. Conversely, it implies that classifying the event as “not a pandemic” is just as imprecise.

This isn’t a full answer as to what a pandemic is ontologically, but it does shed light on the difficulties of calling it “over” – and illustrates well that there will be disagreement about it.

Author

Associate professor in Computer Science, University of Cape Town

MARTIN LUTALO

RIALDA KOVACEVIC

FENG ZHAO

THE WORLD BANK

Effective knowledge-sharing during pandemic needs to be just in time and demand-driven.

One valuable resource of a country or organization is its knowledge. The COVID-19 pandemic has elevated both the importance of timely knowledge and the need to manage it well. As the world faces the effects of the Omicron variant and the World Health Organization’s global pulse survey warns that essential health services continue to face disruptions across all major health areas in over 90 percent of countries with little to no improvement since early 2021, the less than optimal use of knowledge is not an option.

Decision makers across the globe have relied on timely knowledge to inform strategic decisions to mitigate the health and socioeconomic effects of the pandemic. In a fast-moving environment where information needs are constantly evolving and basic facts are sometimes in dispute, effectively managing knowledge can be a challenge.

We highlight three key lessons we have learned about managing knowledge more effectively during a public health crisis.

Effective knowledge-sharing needs to be just in time and demand-driven

A crisis warrants demand-driven knowledge that is just in time rather than just in case. To make this happen, it is essential to create regular learning platforms for stakeholders to share experiences and lessons learned, with a feedback loop to identify and fill remaining knowledge gaps, while ensuring consistency of messaging. It is far better to overshare knowledge than to risk under sharing it.

To promote an open exchange of ideas and fill knowledge gaps, our teams have organized virtual briefings providing the latest and most reliable knowledge and know-how to guide decision making combined with just-in-time webinars on topics addressing specific aspects of countries’ COVID-19 prevention and containment efforts. In the first 12 to 18 months of the pandemic, over 100 webinars were held, reaching more than 10,000 participants across the globe.

The choice of webinar topics has been demand-driven, the fruit of consultations with a host of internal and external sources, including colleagues from external partner organizations.

A forum for country knowledge-sharing and learning can generate a snowball effect

Creating a forum for policymakers and country practitioners to share their respective experiences, lessons learned, and best practices through regular webinars is important in helping countries during a crisis and can spur further learning and the exchange of ideas. Countries need to understand what others are doing as that is far faster and far less costly in times when learning and practicing are simultaneous.

Our experience has shown that not only are the Bank’s clients and external partners enriched by the knowledge shared, but they are also inspired. For example, following a webinar in mid-2020 entitled “Dealing with Concurring Epidemics in the Time of COVID-19: Experiences in Latin America,” the country speakers from Brazil, Colombia, Mexico, and Peru went on to create a Latin American framework and started sharing their experiences in managing the pandemic.

In the same vein, staff across the Bank’s regions have shared materials including briefs, presentations, webinar recordings, and summaries of the learning events with policymakers in the countries where they work. Such examples include knowledge briefs that are meant to respond to the immediate and longer-term learning in areas such as the private sector, or supply chain, to name a few, as we help countries strengthen their health systems.

Partnerships boost knowledge acquisition and sharing and can help reach diverse audiences

Partnerships are especially important when dealing with a pandemic where countries and development agencies are eager to acquire and share knowledge at speed. By creating joint learning platforms, partner agencies can share critical knowledge with bigger audiences far quicker while providing consistent messaging. To this end, the Bank has tapped into its convening power to promote learning and sharing of knowledge.

Leveraging its membership of the Access to COVID-19 Tools Accelerator (ACT-A), a global collaboration of governments, scientists, businesses, civil society, philanthropists, and global health organizations (the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, CEPI, FIND, Gavi, the Global Fund, Unitaid, Wellcome, UNICEF, and the WHO), we have been able to use its macro-stage and contribute to learning at large scale.

As co-lead of ACT-A’s Health Systems Response Connector (HSRC), the Bank hosted a learning and knowledge-sharing platform, enabling countries to present country-level know-how of health systems strengthening as they respond to COVID-19. The platform attracted participants across multiple agencies and countries across the globe. Topics for knowledge-sharing events ranged from challenges and solutions to protecting the health workforce, addressing supply chain bottlenecks, health financing and budgetary dialogues, frontline services assessments, and the value of community engagement in the pandemic, to the role of the private sector in COVID-19 vaccination.

Countries have shared how urgency yields ingenuity. For instance, Ghana’s mPharma health care technology company facilitated addressing testing capacity constraints faced by the public sector. Tunisia shared its experience of conducting research in a pandemic, as it addressed testing of COVID-19. Kenya’s facility assessment on the provision of services and availability of various commodities allowed it to prioritize areas in need of more investment and financing.

The Bank, in collaboration with WHO, and other ACT-A partners has created a Knowledge Bank depository to host various tools, guidance notes, technical briefs, and case studies produced by all ACT-A partner agencies. The goal is simple: make the latest COVID-19 health systems–related knowledge accessible in one place for ease of utilization by countries. Moving forward, this platform is meant to harness cross-country learning, increase country engagement, and update best practices as we learn them.

As countries work to turn the corner in their COVID-19 responses, the optimal use of knowledge will be critical. Countries will need to effectively manage knowledge assets to inform strategic decisions to both mitigate the health and socioeconomic effects of the pandemic and strengthen preparedness for future emergencies.

Authors

Martin Lutalo

Senior Knowledge Management Specialist

MORE BLOGS BY MARTIN

Rialda Kovacevic

Health Specialist

MORE BLOGS BY RIALDA

Feng Zhao

Practice Manager

MORE BLOGS BY FENG