A family of termites has been traversing the world’s oceans for millions of years

IMAGE: DRYWOOD TERMITES WERE THE CENTER OF A RECENTLY PUBLISHED STUDY THAT INVOLVED THREE DECADES OF SAMPLE COLLECTION AND COLLABORATORS FROM ACROSS THE WORLD. BY SEQUENCING THE MITOCHONDRIAL GENOMES, THE RESEARCHERS DISCERNED THAT THIS FAMILY HAS MADE AT LEAST 40 OCEANIC VOYAGES IN THE LAST 50 MILLION YEARS. view more

CREDIT: ALEŠ BUČEK

Highlights

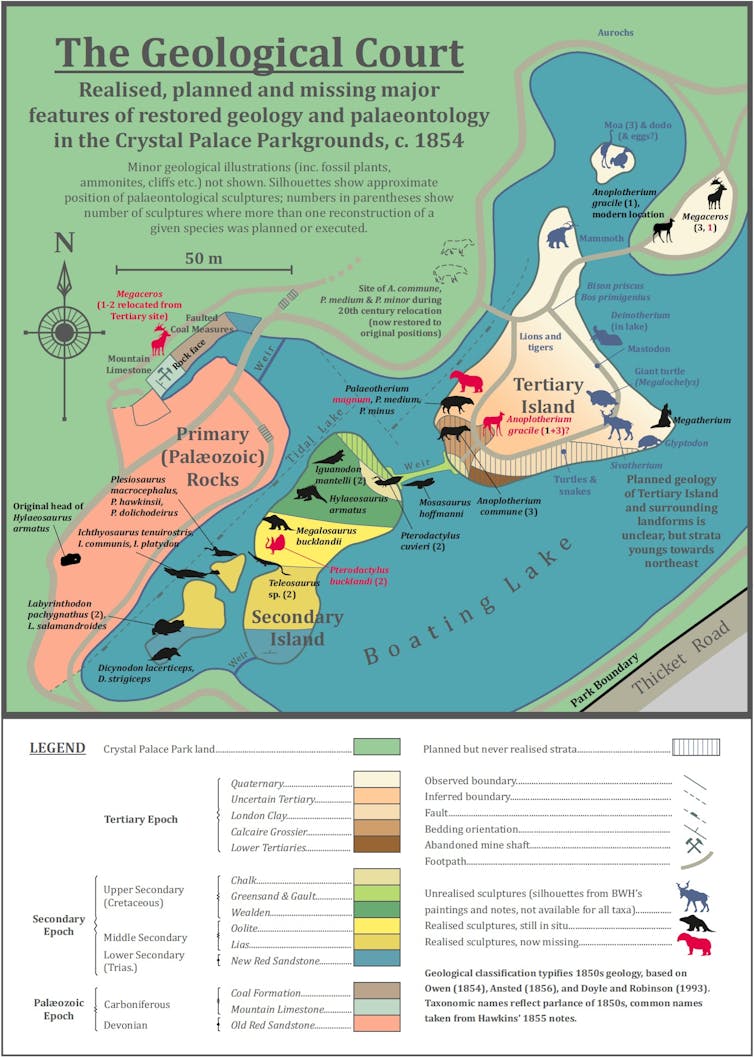

- A new study has mapped out the natural history of drywood termites—the second largest family of termites.

- Drywood termites form small colonies primarily in wood and are generally thought of as primitive termites but very little is actually known about the family.

- By sequencing the mitochondrial genomes of 120 species found across the world, the researchers discerned that this family has made at least 40 oceanic voyages in the last 50 million years.

- The study also confirmed that some species have, in recent centuries, hitched a ride with humans to reach far-flung islands.

- Furthermore, it cast doubt on the common assumption that drywood termites have a primitive lifestyle as, among the oldest lineages in the family, there are species that do not exhibit this lifestyle.

Press release

Termites are a type of cockroach that split from other cockroaches around 150 million years ago and evolved to live socially in colonies. Today, there are many different kinds of termites. Some form large colonies with millions of individuals, which tend to live in connected tunnels in the soil. Others, including most species known as drywood termites, form much smaller colonies of less than 5000 individuals, and live primarily in wood.

Researchers from the Evolutionary Genomics Unit at the Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology Graduate University (OIST), alongside a network of collaborators from across the world, have mapped out the natural history of drywood termites—the second largest family of termites—and revealed a number of oceanic voyages that accelerated the evolution of their diversity. The research, published in Molecular Biology and Evolution, shines light on where termites originated and how and when they spread across the globe. It also confirms that some species have, in recent centuries, hitched a ride with humans to reach far-flung islands.

“Drywood termites, or Kalotermitidae, are often thought of as primitive because they split from other termites quite early, around 100 million years ago, and because they appear to form smaller colonies,” said Dr. Aleš Buček, OIST Postdoctoral Researcher and lead author of the study. “But very little is actually known about this family.”

Dr. Buček went on to explain how, before this study, there was very little molecular data on the family and the little understanding of the relationships between the different species that was known was based on their appearance. Previous research had focused on one genus within the family that contains common pest species, often found within houses.

To gain overarching knowledge, the researchers collected hundreds of drywood termite samples from around the world over a timespan of three decades. From this collection, they selected about 120 species, some of which were represented by multiple samples collected in different locations. This represented over a quarter of Kalotermitidae diversity. Most of these samples were brought to OIST where the DNA was isolated and sequenced.

By comparing the genetic sequences from the different species, the researchers constructed an extensive family tree of the drywood termites.

They found that drywood termites have made more oceanic voyages than any other family of termites. They’ve crossed oceans at least 40 times in the past 50 million years, travelling as far as South America to Africa, which, over a timescale of millions of years, resulted in the diversification of new drywood termite species in the newly colonized places.

“They’re very good at getting across oceans,” said Dr. Buček. “Their homes are made of wood so can act as tiny ships.”

The researchers found that most of the genera originated in southern America and dispersed from there. It takes a scale of millions of years for one species to split into several after a move. The research also confirmed that, more recently, dispersals have largely been mediated by humans.

Furthermore, this study has cast doubt on the common assumption that drywood termites have a primitive lifestyle. Among the oldest lineages in the family, there are termite species that do not have a primitive lifestyle. In fact, they can form large colonies across multiple pieces of wood that are connected by tunnels underground.

“This study only goes to highlight how little we know about termites, the diversity of their lifestyles, and the scale of their social lives,” stated Prof. Tom Bourguignon, Principal Investigator of OIST’s Evolutionary Genomics Unit and senior author of the study. “As more information is gathered about their behavior and ecology, we’ll be able to use this family tree to find out more about the evolution of sociality in insects and how termites have been so successful.”

CAPTION

The researchers collected samples of drywood termites from around the world. The numbers listed on this map are the number of samples collected from each area.

CREDIT

OIST

CAPTION

By comparing the mitochondrial genomes of 120 species of drywood termites, the researchers constructed a comprehensive family tree, revealing insights on how termites diversified and spread across the world.

CREDIT

OIST

JOURNAL

Molecular Biology and Evolution

METHOD OF RESEARCH

Data/statistical analysis

SUBJECT OF RESEARCH

Animals

ARTICLE TITLE

Molecular Phylogeny Reveals the Past Transoceanic Voyages of Drywood Termites (Isoptera, Kalotermitidae)