Jamie Carter

Fri, August 11, 2023

Venus as a razor-thin crescent as it nears inferior conjunction with the sun.

You may have noticed in recent weeks that the planet Venus has slipped from the post-sunset sky, slimming into a crescent shape as it drops from view. Its reign as the bright "Evening Star" in 2023 is over, as a relatively rare celestial phenomenon takes shape.

On Aug. 13, Venus will appear to be between Earth and the sun, which astronomers describe as being at inferior conjunction. It's purely a line-of-sight phenomenon, and from Earth's point of view it can only happen to two planets in the solar system — Mercury and Venus — both of which are inferior planets, which means they are closer to the sun than Earth. The outer planets, which lie farther from the sun than Earth, are called superior planets by astronomers.

Another way of understanding Venus at inferior conjunction is to think of it as in its "new" phase, much as a new moon sits between Earth and the sun. Just like a new moon, Venus at inferior conjunction will be virtually invisible to us on Earth. On Aug. 13, the planet will be completely lost in the sun's glare and impossible to observe. This phenomenon happens once every 19 months, according to EarthSky, because Venus' orbit around the sun takes just 225 days (compared with Earth's 365).

As Venus has been approaching inferior conjunction, it's been thinning to a slim crescent, just as the moon becomes a waning crescent on its way to becoming a new moon. Appearing closer to the sun with each passing day, Venus has been sinking lower to the horizon in the post-sunset western sky. As well as losing latitude, it's also been losing light. As the angle between it and the sun has been reducing, on Earth we've been able to see less and less sunlight reflected from Venus.

Venus won't appear to cross the sun's disk on Aug. 13, instead passing just 7.7 degrees to its south and be just 0.9% illuminated, according to BBC Sky At Night magazine. The moment when the planet appears to pass across the disk of the sun as seen from Earth is called a transit of Venus, which last happened on June 5 to 6, 2012. A transit won't happen again until Dec. 10 to 11, 2117.

— The 'man in the moon' may be hundreds of millions of years older than we thought

Venus' trip into the sun's glare will be brief. Venus and Earth are in an 8:13 resonance, so from Earth's point of view, Venus orbits the sun 13 times in every eight Earth years, according to The Planetary Society. A week or two after its inferior conjunction, Venus will have moved sufficiently away from the sun's glare to emerge into the dawn sky and begin its appearance as the "Morning Star". It will reach its highest point in the sky on Oct. 23 as it appears 46.4 degrees west of the sun, according to Astro Pixels. That farthest point from the sun is called its greatest elongation west.

Venus reached superior conjunction (appearing to go behind the sun) on June 4, 2024, achieving its greatest elongation east in the post-sunset sky on Jan. 10, 2025, according to Timeanddate.com.

If you're looking to photograph Venus, the upcoming Perseid meteor shower or the night sky in general, don't miss our guide on how to photograph meteor showers, as well as our best cameras for astrophotography and best lenses for astrophotography.

This story was provided by Livescience.

|

| THE MORNING STAR IS THE EVENING STAR |

Instruments for NASA's VERITAS Venus mission get a test in Iceland (photos)

Stefanie Waldek

Fri, August 11, 2023

a drone alights on the hand of a man standing in the middle of a black lava field with mountains in the background

NASA's VERITAS Venus mission might be on hold, but team members continue to test out its gear here on Earth.

The German Aerospace Center (known by the German acronym DLR), a VERITAS mission partner, is conducting field tests in Iceland this summer, using its airborne F-SAR radar sensor and an infrared imager called V-EMulator to study lava flows. As Venus is expected to have a volcanic surface, the volcanic landscapes of Iceland serve as a strong analog for what VERITAS might find on our neighboring planet.

"Characterizing and measuring the extent and type of volcanic and tectonic processes on Venus is key to understanding the evolution of the surface of Venus and rocky planets in general," Sue Smrekar, the principal investigator for VERITAS at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Southern California, said in a statement.

Related: Here's every successful Venus mission humanity has ever launched

two people stand on a black lava field with a white insrument on a black tripod

During two weeks of field operations, scientists and researchers from DLR and JPL will use the F-SAR radar system mounted on DLR's Dornier 228-212 aircraft to collect imaging data from Iceland's surface. Simultaneously, teams are collecting data and samples on the ground for laboratory analysis to supplement the radar data.

DLR is also testing V-EMulator, a prototype for the eventual Venus Emissivity Mapper that will be installed on VERITAS (whose name is short for "Venus Emissivity, Radio Science, InSAR, Topography And Spectroscopy").

"This will be of tremendous help to us in characterizing the mineralogical composition and origin of the major geologic terrains on the Venusian surface when VEM delivers 'true' Venus data during the mission phase," Solmaz Adeli, of DLR's Institute of Planetary Research, said in the same statement.

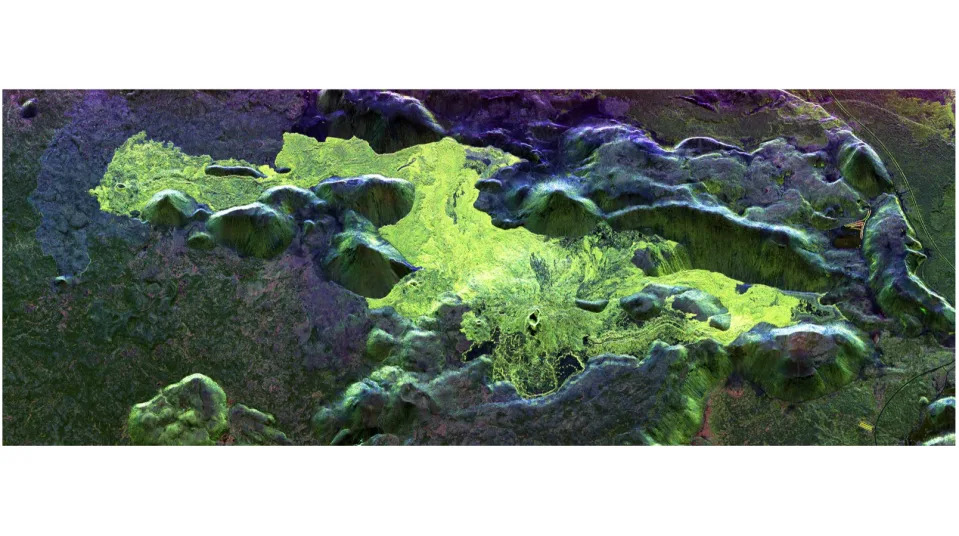

radar image of a lava field, featuring greenish patches of fresher lava against a dark background of older deposits.

RELATED STORIES:

— Problems with NASA asteroid mission Psyche delay Venus probe's launch to 2031

— NASA Venus mission VERITAS becomes collateral damage amid budget pressures

— Venus may have supported life billions of years ago

NASA intended VERITAS to launch in 2027, but due to institutional troubles at JPL, among other issues, the mission has been delayed indefinitely. It is expected that VERITAS might launch in the early 2030s, though mission funding has been reduced and further delays might occur.

The agency is also developing another Venus mission, called DAVINCI ("Deep Atmosphere Venus Investigation of Noble gases, Chemistry, and Imaging"), which is scheduled to reach the planet in the early 2030s. Europe's EnVision probe, another Venus effort, is expected to get off the ground in that same general time frame as well.

As these three missions show, scientific interest in the second planet from the sun has surged over the past few years. Researchers increasingly view Venus as a possible abode for life, both in the ancient past and in the present day. Life as we know it cannot exist on the planet's scorching-hot surface today, but conditions about 30 miles (50 kilometers) up in the clouds are much more Earth-like.