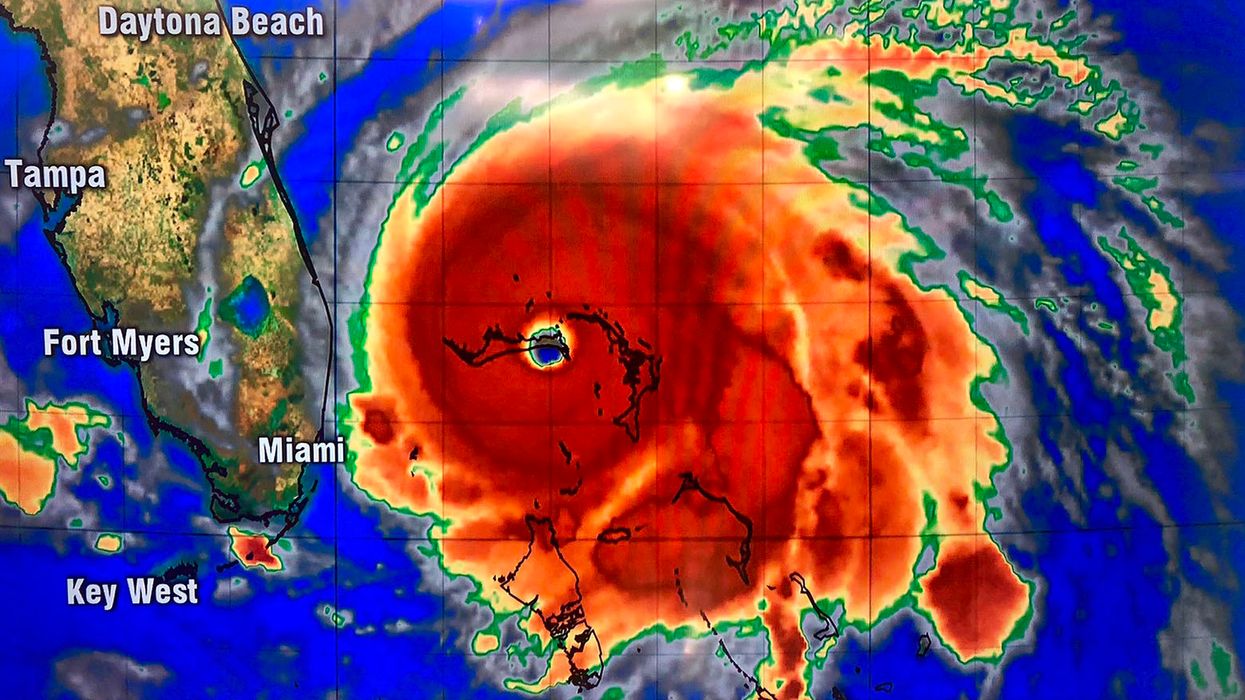

Hurricane Dorian image via Twitter Screengrab

Hurricane forecasts are about to get a whole lot worse

October 13, 2023

Winter is still weeks away, but meteorologists are already talking about a snowy winter ahead in the southern Rockies and the Sierra Nevada. They anticipate more storms in the U.S. South and Northeast, and warmer, drier conditions across the already dry Pacific Northwest and the upper Midwest.

One phrase comes up repeatedly with these projections: a strong El Niño is coming.

It sounds ominous. But what does that actually mean? We asked Aaron Levine, an atmospheric scientist at the University of Washington whose research focuses on El Niño.

NOAA explains in animations how El Niño forms.

What is a strong El Niño?

During a normal year, the warmest sea surface temperatures are in the western Pacific and the Indian Ocean, in what’s known as the Indo-Western Pacific warm pool.

But every few years, the trade winds that blow from east to west weaken, allowing that warm water to slosh eastward and pile up along the equator. The warm water causes the air above it to warm and rise, fueling precipitation in the central Pacific and shifting atmospheric circulation patterns across the basin

This pattern is known as El Niño, and it can affect weather around the world.

The box shows the Niño 3.4 region as El Niño begins to develop in the tropical Pacific, from January to June 2023.

NOAA Climate.gov

A strong El Niño, in the most basic definition, occurs once the average sea surface temperature in the equatorial Pacific is at least 1.5 degrees Celsius (2.7 Fahrenheit) warmer than normal. It’s measured in an imaginary box along the equator, roughly south of Hawaii, known as the Nino 3.4 Index.

But El Niño is a coupled ocean-atmosphere phenomenon, and the atmosphere also plays a crucial role.

What has been surprising about this year’s El Niño – and still is – is that the atmosphere hasn’t responded as much as we would have expected based on the rising sea surface temperatures.

Is that why El Niño didn’t affect the 2023 hurricane season the way forecasts expected?

The 2023 Atlantic hurricane season is a good example. Forecasters often use El Niño as a predictor of wind shear, which can tear apart Atlantic hurricanes. But with the atmosphere not responding to the warmer water right away, the impact on Atlantic hurricanes was lessened and it turned out to be a busy season.

The atmosphere is what transmits El Niño’s impact. Heat from the warm ocean water causes the air above it to warm and rise, which fuels precipitation. That air sinks again over cooler water.

The rising and sinking creates giant loops in the atmosphere called the Walker Circulation. When the warm pool’s water shifts eastward, that also shifts where the rising and sinking motions happen. The atmosphere reacts to this change like ripples in a pond when you throw a stone in. These ripples affect the jet stream, which steers weather patterns in the U.S.

This year, in comparison with other large El Niño events – such as 1982-83, 1997-98 and 2015-16 – we’re not seeing the same change in where the precipitation is happening. It’s taking much longer to develop, and it’s not as strong.

Part of that, presumably, is related to the whole tropics being very, very warm. But this is still an emerging field of research.

How El Niño will change with global warming is a big and open question. El Niño only happens every few years, and there’s a fair amount of variability between events, so just getting a baseline is tough.

Winter is still weeks away, but meteorologists are already talking about a snowy winter ahead in the southern Rockies and the Sierra Nevada. They anticipate more storms in the U.S. South and Northeast, and warmer, drier conditions across the already dry Pacific Northwest and the upper Midwest.

One phrase comes up repeatedly with these projections: a strong El Niño is coming.

It sounds ominous. But what does that actually mean? We asked Aaron Levine, an atmospheric scientist at the University of Washington whose research focuses on El Niño.

NOAA explains in animations how El Niño forms.

What is a strong El Niño?

During a normal year, the warmest sea surface temperatures are in the western Pacific and the Indian Ocean, in what’s known as the Indo-Western Pacific warm pool.

But every few years, the trade winds that blow from east to west weaken, allowing that warm water to slosh eastward and pile up along the equator. The warm water causes the air above it to warm and rise, fueling precipitation in the central Pacific and shifting atmospheric circulation patterns across the basin

This pattern is known as El Niño, and it can affect weather around the world.

The box shows the Niño 3.4 region as El Niño begins to develop in the tropical Pacific, from January to June 2023.

NOAA Climate.gov

A strong El Niño, in the most basic definition, occurs once the average sea surface temperature in the equatorial Pacific is at least 1.5 degrees Celsius (2.7 Fahrenheit) warmer than normal. It’s measured in an imaginary box along the equator, roughly south of Hawaii, known as the Nino 3.4 Index.

But El Niño is a coupled ocean-atmosphere phenomenon, and the atmosphere also plays a crucial role.

What has been surprising about this year’s El Niño – and still is – is that the atmosphere hasn’t responded as much as we would have expected based on the rising sea surface temperatures.

Is that why El Niño didn’t affect the 2023 hurricane season the way forecasts expected?

The 2023 Atlantic hurricane season is a good example. Forecasters often use El Niño as a predictor of wind shear, which can tear apart Atlantic hurricanes. But with the atmosphere not responding to the warmer water right away, the impact on Atlantic hurricanes was lessened and it turned out to be a busy season.

The atmosphere is what transmits El Niño’s impact. Heat from the warm ocean water causes the air above it to warm and rise, which fuels precipitation. That air sinks again over cooler water.

The rising and sinking creates giant loops in the atmosphere called the Walker Circulation. When the warm pool’s water shifts eastward, that also shifts where the rising and sinking motions happen. The atmosphere reacts to this change like ripples in a pond when you throw a stone in. These ripples affect the jet stream, which steers weather patterns in the U.S.

This year, in comparison with other large El Niño events – such as 1982-83, 1997-98 and 2015-16 – we’re not seeing the same change in where the precipitation is happening. It’s taking much longer to develop, and it’s not as strong.

Part of that, presumably, is related to the whole tropics being very, very warm. But this is still an emerging field of research.

How El Niño will change with global warming is a big and open question. El Niño only happens every few years, and there’s a fair amount of variability between events, so just getting a baseline is tough.

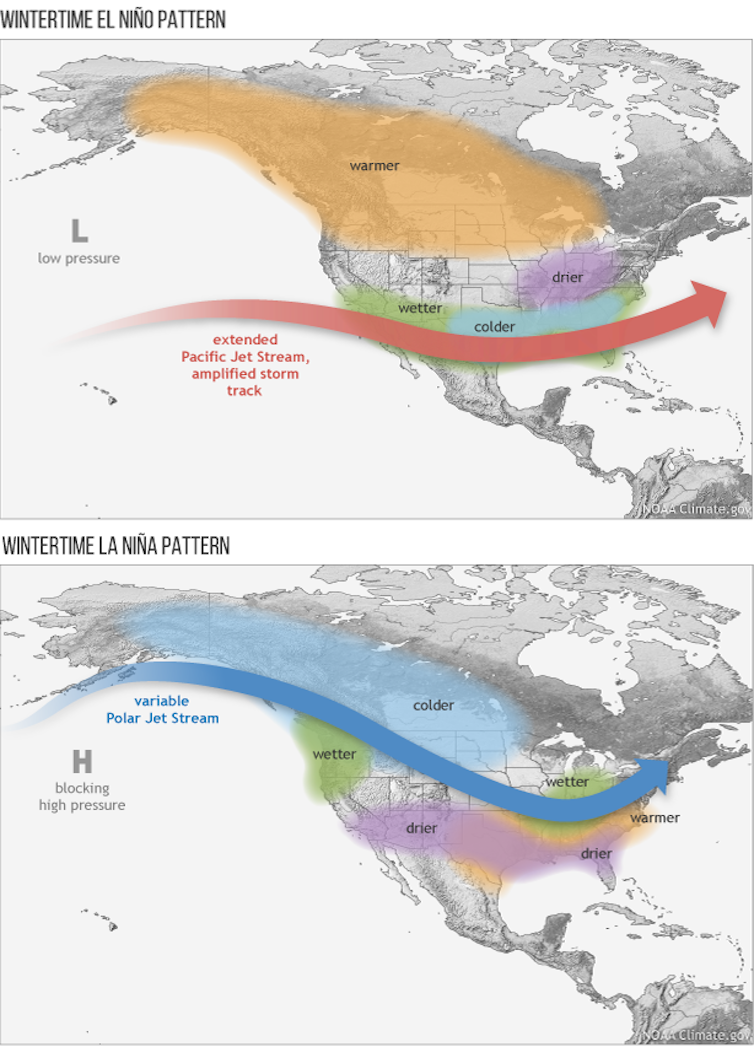

What does a strong El Niño typically mean for US weather?

During a typical El Niño winter, the U.S. South and Southwest are cooler and wetter, and the Northwest is warmer and drier. The upper Midwest tends to be drier, while the Northeast tends to be a little wetter.

The likelihood and the intensity generally scale with the strength of the El Niño event.

El Niño has traditionally been good for the mountain snowpack in California, which the state relies for a large percentage of its water. But it is often not so good for the Pacific Northwest snowpack.

The jet stream takes a very different path in a typical El Niño vs. La Niña winter weather pattern. But these patterns have a great deal of variability. Not every El Niño or La Niña year is the same. NOAA Climate.gov

The jet stream plays a role in that shift. When the polar jet stream is either displaced very far northward or southward, storms that would normally move through Washington or British Columbia are steered to California and Oregon instead.

What do the forecasts show for 2023?

Whether forecasters think a strong El Niño will develop depends on whose forecast model they trust.

This past spring, the dynamical forecast models were already very confident about the potential for a strong El Niño developing. These are big models that solve basic physics equations, starting with current oceanic and atmospheric conditions.

However, statistical models, which use statistical predictors of El Niño calculated from historical observations, were less certain.

Even in the most recent forecast model outlook, the dynamical forecast models were predicting a stronger El Niño than the statistical models were.

If you go by just a sea surface temperature-based El Niño index, the forecast is for a fairly strong El Niño.

But the indices that incorporate the atmosphere are not responding in the same way. We’ve seen atmospheric anomalies – as measured by cloud height monitored by satellites or sea-level pressure at monitoring stations – on and off in the Pacific since May and June, but not in a very robust fashion. Even in September, they were nowhere near as large as they were in 1982, in terms of overall magnitude.

We’ll see if the atmosphere catches up by wintertime, when El Niño peaks.

How long do El Niños last?

Often during El Niño events – particularly strong El Niño events – the sea surface temperature anomalies collapse really quickly during the Northern Hemisphere spring. Almost all end in April or May.

One reason is that El Niño sows the seeds of its own demise. When El Niño happens, it uses up that warm water and the warm water volume shrinks. Eventually, it has eroded its fuel.

The surface can stay warm for a while, but once the heat from the subsurface is gone and the trade winds return, the El Niño event collapses. At the end of past El Niño events, the sea surface anomaly dropped very fast and we saw conditions typically switch to La Niña – El Niño’s cooler opposite.

Aaron Levine, Atmospheric Research Scientist, CICOES, University of Washington

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.