LONG READ

Trump, Twitter, and truth judgments: The effects of “disputed” tags and political knowledge on the judged truthfulness of election misinformation

Misinformation has sown distrust in the legitimacy of American elections. Nowhere has this been more concerning than in the 2020 U.S. presidential election wherein Donald Trump falsely declared that it was stolen through fraud. Although social media platforms attempted to dispute Trump’s false claims by attaching soft moderation tags to his posts, little is known about the effectiveness of this strategy. We experimentally tested the use of “disputed” tags on Trump’s Twitter posts as a means of curbing election misinformation. Trump voters with high political knowledge judged election misinformation as more truthful when Trump’s claims included Twitter’s disputed tags compared to a control condition. Although Biden voters were largely unaffected by these soft moderation tags, third-party and non-voters were slightly less likely to judge election misinformation as true. Finally, little to no evidence was found for meaningful changes in beliefs about election fraud or fairness. These findings raise questions about the effectiveness of soft moderation tags in disputing highly prevalent or widely spread misinformation.

September 11, 2024

Peer Reviewed

Research Questions

- Do soft moderation tags warning about “disputed” information influence the judged truthfulness of election misinformation alleged by Donald Trump following the 2020 U.S. presidential election?

- Does the effectiveness of attaching “disputed” tags to Donald Trump’s election misinformation depend upon a person’s political knowledge or pre-existing belief about fraud?

Essay Summary

- A sample of U.S. Americans (n = 1,078) were presented with four social media posts from Donald Trump falsely alleging election fraud in the weeks following the 2020 election. Participants were randomly assigned to the disputed tag or control condition, with only the former including soft moderation tags attached to each of Trump’s false allegations. Participants rated the truthfulness of each allegation and answered questions about election fraud and fairness. Individual differences in political knowledge and verbal ability were measured before the election.

- There was little to no evidence that Twitter’s disputed tags decreased the judged truthfulness of election misinformation or meaningfully changed pre-existing beliefs in election fraud or fairness.

- Trump voters with high political knowledge were more likely to perceive election misinformation as truthful when Donald Trump’s posts included disputed tags versus not.

- Trump voters that were initially skeptical of election fraud in the 2020 election were more likely to judge election misinformation as truthful when Donald Trump’s posts included disputed tags.

Implications

In recent years, misinformation has undermined trust in the legitimacy of American democratic elections. Nowhere has this been more concerning than in the 2020 U.S. presidential election, which saw the sitting president, Donald Trump, falsely declare that the election was stolen through widespread fraud (Timm, 2020). This culminated in many hundreds of Trump’s supporters storming the U.S. Capitol building to stop certification of challenger Joe Biden’s victory (Zengerle et al., 2021). This is not a fringe belief (Blanchar & Norris, 2021); national polls indicate that majorities of Republicans and conservatives endorse the belief that Trump probably or definitely won the election (Ipsos, 2020; Pew Research Center, 2021).

Although social media companies like Twitter (now X) and Facebook attempted to dispute Trump’s false claims of election fraud by attaching soft moderation tags to his posts (Graham & Rodriguez, 2020), little is known about the effectiveness of this strategy. The present experiment tests the effectiveness of attaching “disputed” tags to Trump’s Twitter posts as a means of curbing election misinformation about voter fraud among U.S. Americans. We assessed individual differences in political knowledge (i.e., basic facts about American politics) and verbal ability to examine whether misinformation susceptibility depends on domain knowledge (Lodge & Taber, 2013; Tappin et al., 2021).

Disputing misinformation

A wide array of interventions for curbing misinformation have been applied with varying results (Ziemer & Rothmund, 2024). Among these, fact-checking approaches are the most common; they attempt to refute or dispute misleading or false information through tagging (or flagging), social invalidation, or expert corrections. Tagging simply involves labeling a claim as false or disputed, in contrast to more elaborate fact checks like social invalidation through corrective comments below a social media post or expert-based corrections that provide detailed rebuttals from professional entities or scientific organizations. However, because tagging misinformation on social media platforms tends to be reactive rather than proactive, it typically addresses misinformation only after it has been identified and spread. This reactive nature mirrors the broader challenges of fact-checking, which often lags behind the rapid dissemination of false claims. A more natural test would involve assessing truth judgments of ongoing false claims that extend from recognizable or existing beliefs and narratives. The present research experimentally tests the efficacy of Twitter’s “disputed” tag as a form of soft moderation to reduce belief in timely, real-world, and widely propagated misinformation that aligns or conflicts with partisans’ beliefs. Specifically, we considered the special case of Donald Trump’s false claims about election fraud following the 2020 U.S. presidential election, where people very likely have strong pre-existing beliefs (Blanchar & Norris, 2021).

Evidence surrounding the use of misinformation tags on social media posts largely supports their efficacy in reducing belief and sharing (Koch et al., 2023; Martel & Rand, 2023; Mena, 2020). However, these effects are relatively small and depend on tag precision (Martel & Rand, 2023). For instance, Clayton et al. (2020) observed that, whereas tagging fake news headlines as “disputed” slightly reduced their perceived accuracy compared to a control condition, this approach was less effective than tagging fake headlines as “rated false.” Tagging posts as “false” is clearer than tagging them as “disputed,” with the latter possibly implying mixed evidence and/or legitimate disagreement. However, although Pennycook et al. (2020) reported similar findings, they also found that these tags slightly increased the perceived accuracy of other fake but non-tagged news headlines presented alongside tagged headlines. The presence of tagged warnings on some but not other information may lead people to guess that anything not tagged is probably accurate.

Although major reviews indicate that corrections are generally effective at reducing misinformation (Chan et al., 2017; Porter & Wood, 2024), some scholars have suggested the possibility of “backfire effects,” where corrective information may arouse cognitive dissonance—an uncomfortable psychological tension from holding incompatible thoughts or beliefs—leading people to double-down on their initial beliefs instead of changing them (Nyhan & Reifler, 2010; Nyhan et al., 2013; see also Festinger et al., 1956). Nevertheless, these effects are quite rare, and many subsequent tests have yielded contradictory evidence (Haglin, 2017; Lewandowski et al., 2020; Nyhan et al., 2020; Wood & Porter, 2019). Even so, attempts to correct or dispute misinformation sometimes do fail. For instance, people’s beliefs tend to persevere despite being discredited by new information (Anderson, 1995; Ecker & Ang, 2019; Ecker et al., 2022; Ross et al., 1975; Thorson, 2016). Sharevski et al. (2022) reported evidence that tagging Twitter posts for vaccine misinformation during the COVID-19 pandemic failed to change people’s belief in the discredited information. However, using interstitial covers that obscure misleading tweets before they are clicked on effectively reduced the perceived accuracy of misinformation. People also dislike feeling that they are being told what to do, think, or say (Brehm, 1966), and thus attempts to dispute misinformation may spur reactance and paradoxically increase its exposure and prevalence (Ma et al., 2019; Wicklund, 1974). Oeldorf‐Hirsch and colleagues (2020) found that “disputed” tags did not influence the perceived credibility of inaccurate news articles and internet memes. Additionally, DeVerna et al. (2024) employed supervised machine-learning techniques to analyze over 430,000 tweets and found that after official corrections, the spread of false rumors decreased among political liberals but increased among political conservatives. Collectively, these findings suggest that although corrective measures can be effective, their success may depend on how they are implemented and the context in which they are received.

The role of political knowledge

An important factor that may moderate how people process or react to soft moderation tags attached to election misinformation is their level of political knowledge. Lodge and Taber (2013) argue that political knowledge affords partisans greater opportunity to effectively discount or counterargue against information that challenges their beliefs and to reach conclusions congenial to their political identity. Consistently, partisans that score higher in political knowledge demonstrate greater skepticism of counter-attitudinal information and more polarized attitudes following mixed evidence compared to their less knowledgeable peers (Taber et al., 2009; Taber & Lodge, 2006). Moreover, Nyhan et al. (2013) found that challenging Sarah Palin’s “death panel” claims was counterproductive, yielding stronger belief for Palin’s supporters with high political knowledge (for similar findings, see Wiliams Kirkpatrick, 2021).

Another possibility follows a Bayesian account. People may be updating their beliefs based on the strength and reliability of new information, but their prior beliefs, which tend to be associated with their politics or group membership, play a significant role in this process (Jern et al., 2014; Tappin et al., 2021). From this perspective, individuals with greater political knowledge may possess stronger pre-existing beliefs that are more resistant to change, or they may have pertinent prior beliefs that influence the way new corrective information is integrated with their existing beliefs. Cognitive sophistication, including political knowledge, has been shown to increase the effect of partisans’ pre-existing beliefs on their subsequent reasoning (Flynn et al., 2017; Tappin et al., 2021; see also Kahan, 2013). Pennycook and Rand (2021), for example, observed that false beliefs about election fraud and Trump as the winner of the 2020 U.S. presidential election were positively correlated with political knowledge among Trump voters and negatively correlated with political knowledge among Biden voters.

The totality of this work suggests that explicit attempts to dispute misinformation may be likely to fail for partisans higher in political knowledge. Hence, we explored whether political knowledge would moderate the effect of Twitter’s “disputed” tags on Trump voters’ judgments of election misinformation. Verbal ability was measured as a control variable to rule out political knowledge as general cognitive ability. We found that “disputed” tags were generally ineffective at curbing election misinformation among Trump voters. Ironically, these tags may have slightly increased belief in misinformation for those Trump voters with high political knowledge. Additionally, Trump voters who were initially skeptical of mass election fraud were more likely to perceive Donald Trump’s misinformation as truthful when exposed to the disputed tag compared to the control condition. Although Biden voters were unaffected by the inclusion of “disputed” tags, third-party and non-voters were marginally less likely to believe election misinformation in the “disputed” tag condition compared to the control. It is important to note that we did not anticipate that soft moderation “disputed” tags would be counterproductive, or “backfire,” for Trump voters with high political knowledge. Our expectation was that political knowledge would diminish or eliminate the effectiveness of “disputed” tags. We emphasize caution with this particular finding. Consequently, we are more confident in concluding that the effectiveness of “disputed” tags decreased as political knowledge increased among Trump voters.

Limitations and considerations

Our sample consisted of 1,078 adults living in the United States recruited via CloudResearch’s online platform. Although CloudResearch is known to attract highly attentive and engaged participants, its samples are less representative compared to other online participant-sourcing platforms (Stagnaro et al., 2024). It is conceivable that our sample of Trump voters high in political knowledge may possess distinct characteristics, potentially skewing the sample’s representation away from the broader population of similarly informed Trump supporters. This limitation warrants caution when generalizing our findings, as does the specific context of Trump’s false claims surrounding the 2020 U.S. presidential election. This was an unprecedented event in American history, marked by the sitting President’s refusal to concede and repeated assertions of widespread voter fraud. It remains unclear whether similar responses would occur in the context of other, less consequential, divisive, and pervasive instances of misinformation.

Additionally, our analyses focused on a relatively smaller number of Trump voters than Biden voters. Participants were recruited more than a month before the election for a larger longitudinal project, making it difficult to deliberately oversample Trump voters in hindsight. Experimental tests of the effectiveness of “disputed” tags among individuals with varying levels of political knowledge further sliced our sample size of Trump voters. We emphasize caution and reiterate that our finding is more robust regarding the ineffectiveness of “disputed” tags for Trump voters and the diminishing effectiveness of these tags as their political knowledge increases. There should be less confidence in the notion that these tags are counterproductive (or “backfire”) per se. Furthermore, we cannot definitively distinguish between potential mechanisms such as cognitive dissonance, psychological reactance, or Bayesian updating. These limitations highlight opportunities for confirmatory tests in future research.

Findings

Manipulation check and analysis strategy

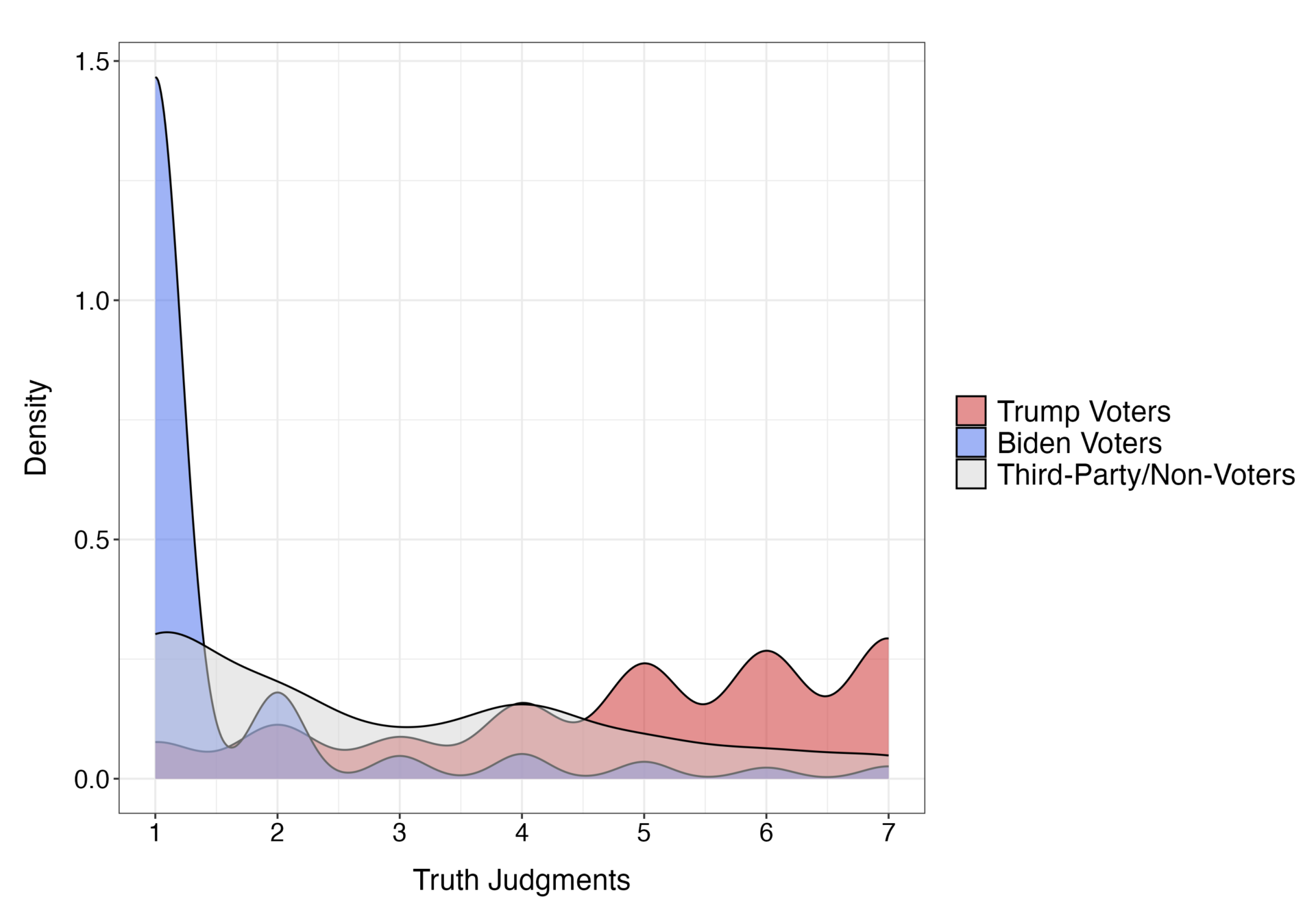

Twelve participants reported conflicting voting decisions between survey waves and were excluded from all analyses. One-hundred four participants failed the attention manipulation check by incorrectly indicating that a disputed tag about misinformation was present in the control condition (n = 57) or not present in the disputed tag condition (n = 47). There was no difference in the pass/fail rate between conditions, χ2(n = 1,078) = 0.79, p = .374, and our findings remained consistent irrespective of whether those failing the attention check were excluded from analyses. Hence, we report analyses with these participants included (n = 1,078: 290 Trump voters, 673 Biden voters, and 115 third-party/non-voters) to better simulate the effectiveness of disputed tags on the judged truthfulness of election misinformation. Because distributions of truth judgments varied drastically by voter group (see Figure 1), we separated analyses by voting. We fit linear mixed models with random intercepts of participants and tweets to examine truth judgments of Trump’s false claims about election fraud (four observations per participant given four tweets) using the lme4 and lmerTest packages in R (Bates et al., 2015; Kuznetsova et al., 2017).1 That is, we used a statistical technique that allowed us to consider individual differences between participants and the specific tweets they rated, so we could see how people judged the truthfulness of the claims and ensure that any patterns we found weren’t simply due to one person or tweet being unusual. Voter-specific models included social media condition (-0.5 = control, 0.5 = disputed tag), political knowledge (mean-centered), and their interaction as fixed-effects predictors.

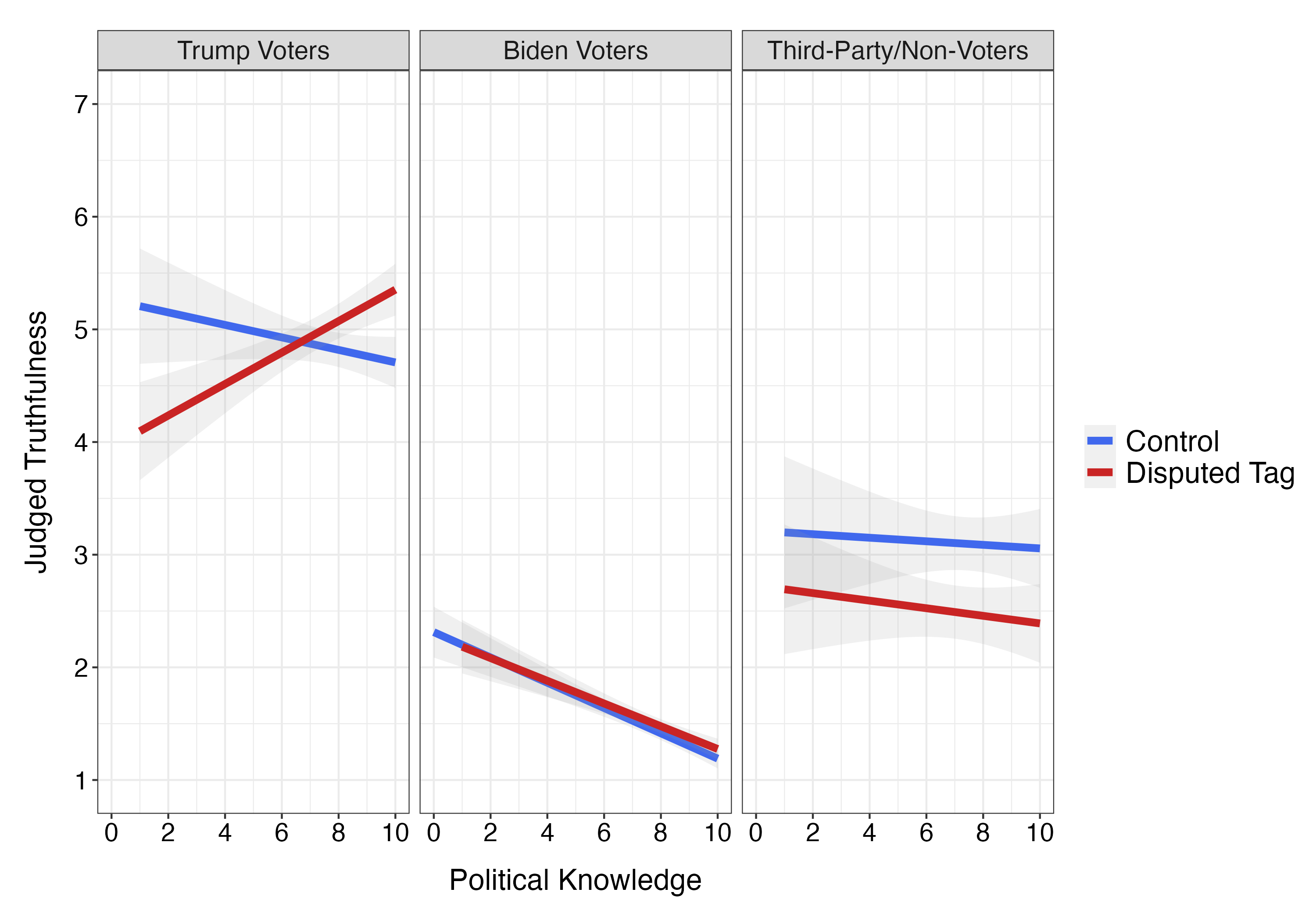

Finding 1: Overall, “disputed” tags were ineffective at curbing misinformation among Trump voters. Trump voters with high political knowledge judged Donald Trump’s election misinformation as more truthful when his posts included disputed tags compared to the control condition.

Illustrated in Figure 2, the model with Trump voters yielded a significant interaction between moderation tag condition and political knowledge, b = 0.20, SE = .09, t = 2.18, p = .030, but no effects of condition, b = 0.16, SE = .19, t = 0.81, p = .420, or political knowledge, b = 0.04, SE = .04, t = 0.94, p = .347. Belief in election misinformation increased with political knowledge in the disputed tag condition, b = 0.14, SE = .06, t = 2.30, p = .022, 95% CI [0.02, 0.26], and it was unrelated to political knowledge in the control condition, b = -0.06, SE = .07, t = 0.85, p = .398, 95% CI [-0.18, 0.07]. Moreover, whereas Trump voters high in political knowledge (+1 SD) reported marginally stronger belief in Trump’s election fraud claims in the disputed tag condition relative to the control condition, b = 0.58, SE = .27, Bonferroni adjusted p = .069, 95% CI [0.04, 1.12], those with low political knowledge (-1 SD) were unaffected by social media condition, b = -0.27, SE = .27, Bonferroni adjusted p = .662, 95% CI [-0.81, 0.27]. In other words, Trump voters with high political knowledge (those in the top 18.1%, scoring above 9) found Trump’s election fraud misinformation to be somewhat more truthful when it had a disputed tag compared to when it didn’t. This difference (d = 0.32) is about one-third of the standard deviation in truthfulness ratings between the two conditions. Controlling for verbal ability did not change these results and the condition by political knowledge interaction remained significant, b = 0.19, SE = .09, t = 2.13, p = .034.

The models for Biden voters and third-party and non-voters revealed no significant interactions between condition and political knowledge, bs = 0.01 and -0.02, SEs = .04 and .13, ts = 0.29 and 0.14, ps = .771 and .888. However, we did observe a significant main effect of political knowledge for Biden voters, b = -0.11, SE = .02, t = 5.45, p < .001, and a marginal effect of social media condition for third-party and non-voters, b = -0.62, SE = .33, t = 1.89, p = .061. Biden voters were less likely to believe Trump’s fraud claims as their political knowledge increased, and third-party and non-voters tended to believe Trump’s fraud claims marginally less in the disputed tag condition relative to the control condition. No other effects emerged, ts < 0.78, ps > .440.

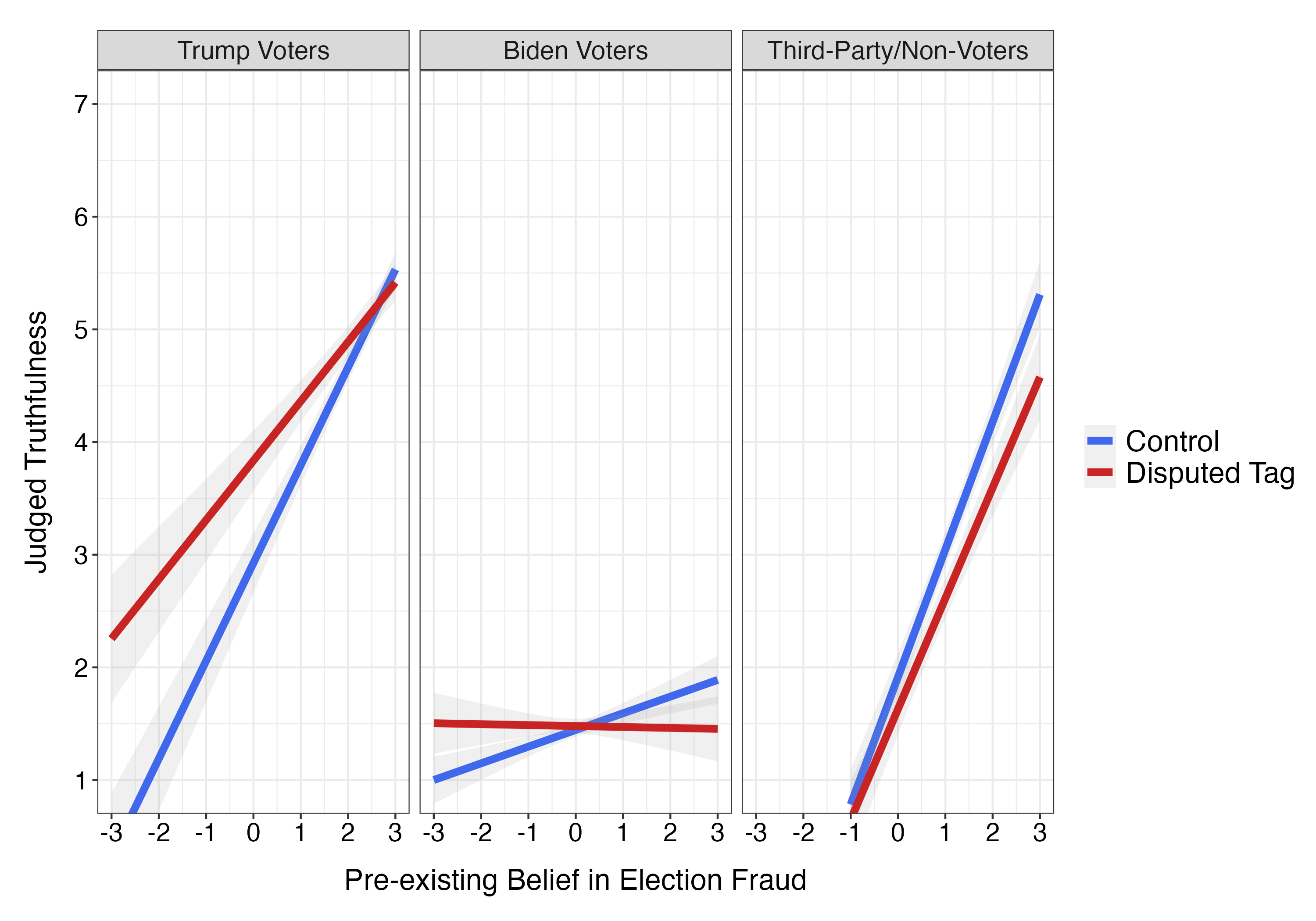

Finding 2: Trump voters that were initially skeptical of mass election fraud were more likely to perceive Donald Trump’s misinformation as truthful in the disputed tag condition compared to the control.

We considered pre-existing belief in voter fraud favoring Biden (vs. Trump) as a predictor in voter-specific models along with moderation tag condition. The model for Trump voters produced a main effect of pre-existing fraud belief, b = 0.70, SE = .07, t = 10.51, p < .001, with stronger belief predicting greater susceptibility to misinformation, and a significant interaction between pre-existing belief and social media condition, b = -0.34, SE = .13, t = 2.57, p = .011. Illustrated in Figure 3, Trump voters relatively skeptical of election fraud benefiting Biden (-1 SD) rated Trump’s claims as more truthful in the disputed tag condition compared to the control condition, b = 0.59, SE = .23, Bonferroni adjusted p = .024, 95% CI [0.13, 1.05]. Conversely, Trump voters that fully (max.) endorsed belief in election fraud were unaffected by the disputed tag manipulation, b = -0.12, SE =.20, Bonferroni adjusted p = 1.000, 95% CI [-0.50, 0.27]. Said differently, Trump voters with minimal to no belief in mass voter fraud benefitting Biden in the 2020 U.S. presidential election (those in the bottom 14.1% of pre-existing belief, scoring less than 1 on the response scale) rated Trump’s election fraud misinformation to be moderately more truthful when it included a “disputed” tag versus when it did not. This difference (d = 0.36) indicates that the increase in perceived truthfulness is roughly one-third of the standard deviation in truthfulness ratings between the two conditions.

The model for third-party and non-voters produced main effects of condition, b = -0.43, SE = .21, t = 2.06, p = .042, and existing fraud belief, b = 1.06, SE = .09, t = 11.86, p < .001, but no interaction, b = -0.15, SE = .18, t = 0.84, p = .403. Those in the disputed tag condition were less likely to judge Trump’s claims as true and pre-existing fraud belief positively predicted susceptibility to misinformation (see Figure 3). Conversely, no significant effects emerged in the model with Biden voters, ts < 1.54, ps > .125. The similar pattern observed among Trump voters and third-party/non-voters, where pre-existing belief in election fraud predicted perceived truthfulness of election misinformation, seems to stem from ample variance in the beliefs and judgments within these groups. In contrast, Biden voters nearly unanimously rejected the notion of election fraud and consistently judged Trump’s claims as false; this lack of variance among Biden voters prevented pre-existing beliefs from predicting their subsequent truth judgments.

Finding 3: Disputed tags failed to meaningfully change pre-existing beliefs about election fraud or fairness.

There was little to no evidence that attaching disputed tags to Trump’s tweets meaningfully changed participants’ pre-existing beliefs about election fraud or fairness, especially for the key target audience of Trump voters (see Appendices A and B).

Methods

A sample of American adults was recruited via CloudResearch’s participant-sourcing platform (Litman et al., 2017) for a longitudinal study on the 2020 U.S. presidential election. Our target sample was set to at least 1,500 participants for the first wave of data collection to achieve a large sample, with the expectation of attrition across three subsequent waves administered in three-week intervals. Totals of 1,556, 1,247, 1,163, and 1,131 respondents completed Wave 1 (October 6–10, 2020), Wave 2 (October 27–31, 2020), Wave 3 (November 17–21, 2020), and Wave 4 (December 8–12, 2020), respectively. Participants’ residences included 49 U.S. states and the District of Columbia (for sample demographics, see supplemental materials on Open Science Framework [OSF]). The present experiment was administered in Wave 4 but included individual difference measures from Wave 1. Measures in Waves 2 and 3 did not concern the present research. After data cleaning procedures to identify duplicate and non-U.S. IP addresses (n = 40; Waggoner et al., 2019) and low-quality data via responses to eight open-ended questions (n = 155; for details, see supplemental materials on OSF), our final sample for data analyses included 1,078 participants. All data cleaning was completed prior to any analyses.

Tweet stimuli, disputed tags, and truth judgments

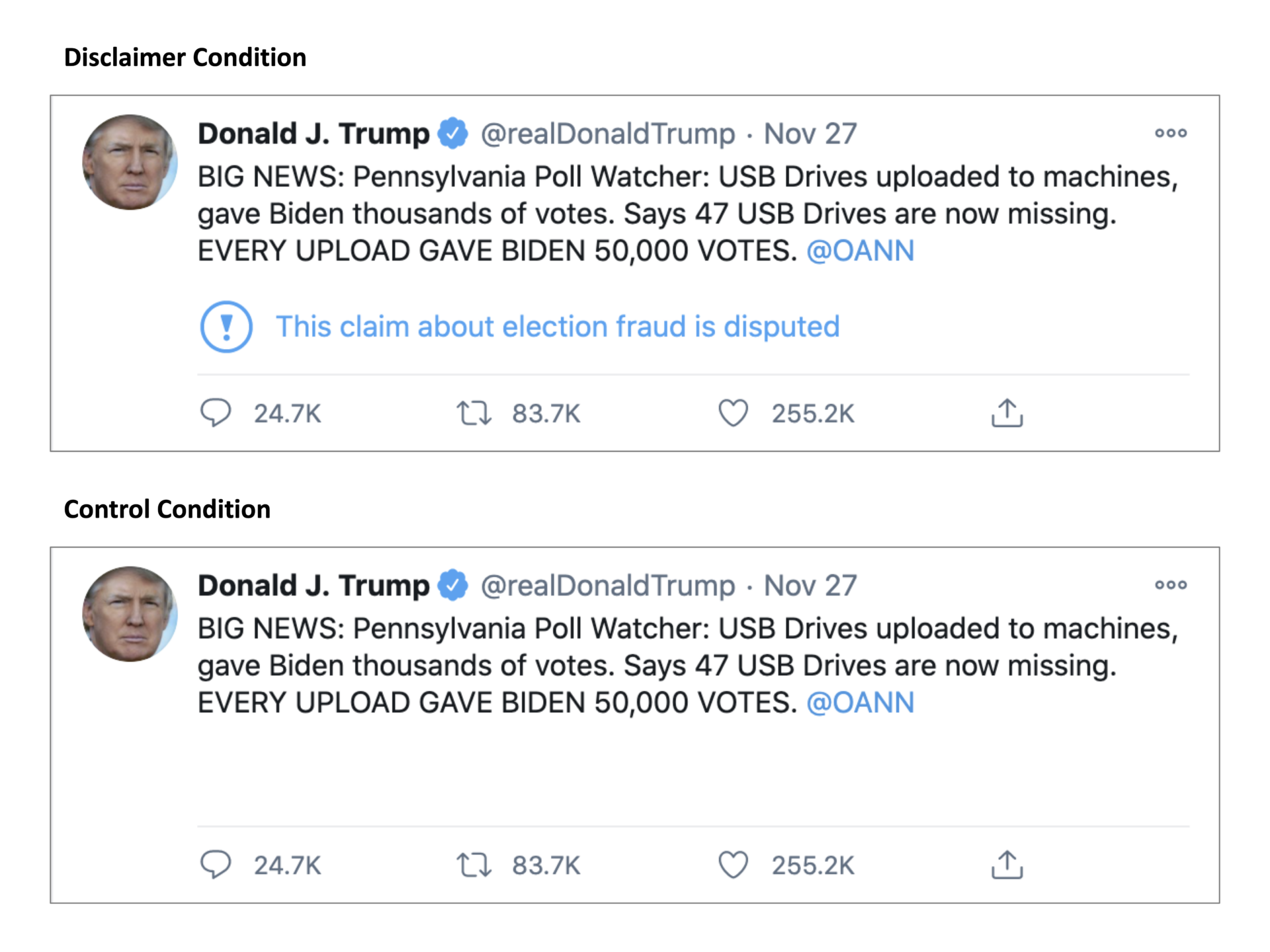

Participants reported how they voted in the 2020 U.S. presidential election between Donald Trump, Joe Biden, Jo Jorgensen or other third-party candidates, and not voting. In Wave 4, they rated the truthfulness of four representative tweets from Donald Trump falsely claiming instances of election fraud. Trump’s tweets were selected as stimuli based on the following criteria: they made specific false claims about election fraud, covered distinct (supposed) events, and did not include images. Depicted in Figure 4, all four tweets included Twitter’s disputed tag (“This claim about election fraud is disputed”) or no additional information (control). Participants were told they would be presented with “actual Tweets made by President Trump” and instructed to “read each Tweet and indicate the extent to which you believe his statement is true or false.” Truth judgments (“Do you believe this statement to be true or false?”) were provided using 7-pt response scales (1 = extremely false, 7 = extremely true). An attentional manipulation check asked if participants recalled whether Trump’s tweets included a tag disputing his claims (“yes,” “no,” or “I can’t remember”). Before and after rating the truthfulness of Trump’s claims, they also indicated their perceptions of voter fraud (“To what extent do you think voter fraud contributed to the results of the 2020 U.S. presidential election?” [-3 = strongly benefited Donald Trump, +3 = strongly benefited Joe Biden]) and election fairness (“As far as you know, do you think the 2020 U.S. presidential election was a free and fair election?” [1 = definitely not, 5 = definitely yes]).

Political knowledge and verbal ability

Adapted from Taber and Lodge (2006), political knowledge was measured using 10 factual questions about American politics (e.g., “Do you happen to know what job or political office is now held by John Roberts? What is it?”, “How much of a majority is required for the U.S. Senate and House to override a presidential veto?”). Political knowledge scores were computed by summing the number of correct responses. To measure verbal ability, participants completed the WordSum Test (Huang & Hauser, 1998). This 10-item vocabulary test is adapted from the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale and strongly correlates with general factor intelligence (Wolfle, 1980). Verbal ability scores were computed by summing the number of correct responses. Both measures were administered before the experiment in Wave 1.

Bibliography

Bates, D., Mächler, M., Bolker, B., & Walker, S. (2015). Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. Journal of Statistical Software, 67(1), 1–48. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v067.i01

Blanchar, J. C., & Norris, C. J. (2021). Political homophily, bifurcated social reality, and perceived legitimacy of the 2020 U.S. presidential election: A four-wave longitudinal study. Analyses of Social Issues and Public Policy, 21(1), 259–283. https://doi.org/10.1111/asap.12276

Brehm, J. W. (1966). A theory of psychological reactance. Academic Press.

Chan, M. S., Jones, C. R., Hall Jamieson, K., & Albarracín, D. (2017). Debunking: A meta-analysis of the psychological efficacy of messages countering misinformation. Psychological Science, 28(11), 1531–1546. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797617714579

Clayton, K., Blair, S., Busam, J. A., Forstner, S., Glance, J., Green, G., Kawata, A., Kovvuri, A., Martin, J., Morgan, E., Sandhu, M., Sang, R., Scholz-Bright, R., Welch, A. T., Wolff, A. G., Zhou, A., & Nyhan, B. (2020). Real solutions for fake news? Measuring the effectiveness of general warnings and fact-check tags in reducing belief in false stories on social media. Political Behavior, 42(4), 1073–1095. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-019-09533-0

DeVerna, M. R., Guess, A. M., Berinsky, A. J., Tucker, J. A., & Jost, J. T. (2024). Rumors in retweet: Ideological asymmetry in the failure to correct misinformation. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 50(1), 3–17. https://doi.org/10.1177/01461672221114222

Ecker, U. K. H., & Ang, L. C. (2019). Political attitudes and the processing of misinformation corrections. Political Psychology, 40(2), 241–260. https://doi.org/10.1111/pops.12494

Ecker, U. K. H., Lewandowsky, S., Cook, J., Schmid, P., Fazio, L. K., Brashier, N., Kendeou, P., Vraga, E. K., & Amazeen, M. A. (2022). The psychological drivers of misinformation belief and its resistance to correction. Nature Reviews Psychology, 1(1), 13–29. https://doi.org/10.1038/s44159-021-00006-y

Festinger, L., Riecken, H. W., & Schachter, S. (1956). When prophecy fails. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Flynn, D. J., Nyhan, B., & Reifler, J. (2017). The nature and origins of misperceptions: Understanding false and unsupported beliefs about politics. Political Psychology, 38(S1), 127–150. https://doi.org/10.1111/pops.12394

Graham, M., & Rodriguez, S. (2020, November 4). Twitter and Facebook race to label a slew of posts making false election claims before all votes counted. CNBC. https://www.cnbc.com/2020/11/04/twitter-and-facebook-label-trump-posts-claiming-election-stolen.html

Haglin, K. (2017). The limitations of the backfire effect. Research & Politics, 4(3). https://doi.org/10.1177/2053168017716547

Huang, M., & Hauser, R. M. (1998). Trends in black-white test score differentials: II. The WORDSUM Vocabulary Test. In U. Neisser (Ed.), The rising curve: Long-term gains in IQ and related measures. American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/10270-011

Ipsos. (2020, November 18). Most Americans agree Joe Biden is rightful winner of 2020 election: Latest Reuters/Ipsos poll shows most approve of how Joe Biden is handling his position of President-elect [Press release]. https://www.ipsos.com/sites/default/files/ct/news/documents/2020-11/topline_reuters_post_election_survey_11_18_2020.pdf

Jern, A., Chang, K. M. K., & Kemp, C. (2014). Belief polarization is not always irrational. Psychological Review, 121(2), 206–224. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0035941

Kahan, D. M. (2013). Ideology, motivated reasoning, and cognitive reflection. Judgment and Decision Making, 8(4), 407–424. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1930297500005271

Koch, T. K., Frischlich, L., & Lermer, E. (2023). Effects of fact-checking warning labels and social endorsement cues on climate change fake news credibility and engagement on social media. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 53(6), 495–507. https://doi.org/ 10.1111/jasp.12959

Kuznetsova, A., Brockhoff, P. B., & Christensen, R. H. B. (2017). lmerTest package: Tests in linear mixed effects models. Journal of Statistical Software, 82(13), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v082.i13

Lewandowsky, S., Cook, J., Ecker, U., Albarracín, D., Kendeou, P. Newman, E. J., Pennycook, G., Porter, E., Rand, D. G., Rapp, D. N., Reifler, J., Roozenbeek, J., Schmid, P., Seifert, C. M., Sinatra, G. M., Swire-Thompson, B., van der Linden, S., Wood, T. J., & Zaragoza, M. S. (2020). The debunking handbook 2020. DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/scholcom/245

Litman, L., Robinson, J., & Abberbock, T. (2017). TurkPrime.com: A versatile crowdsourcing data acquisition platform for the behavioral sciences. Behavior Research Methods, 49(2), 433–442. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-016-0727-z

Lodge, M., & Taber, C. S. (2013). The rationalizing voter. Cambridge University Press.

Ma, Y., Dixon, G., & Hmielowski, J. D. (2019). Psychological reactance from reading basic facts on climate change: The role of prior views and political identification. Environmental Communication, 13(1), 71–86. https://doi.org/10.1080/17524032.2018.1548369

Martel, C., & Rand, D. G. (2023). Misinformation warning labels are widely effective: A review of warning effects and their moderating features. Current Opinion in Psychology, 54, Article 101710. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2023.101710

Mena, P. (2020). Cleaning up social media: The effect of warning labels on likelihood of sharing false news on Facebook. Policy & Internet, 12(2), 165–183. https://doi.org/10.1002/poi3.214

Nyhan, B., Porter, E., Reifler, J., & Wood, T. J. (2020). Taking fact-checks literally but not seriously? The effects of journalistic fact-checking on factual beliefs and candidate favorability. Political Behavior, 42(3), 939–960. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-019-09528-x

Nyhan, B., & Reifler, J. (2010). When corrections fail: The persistence of political misperceptions. Political Behavior, 32(2), 303–330. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-010-9112-2

Nyhan, B., Reifler, J., & Ubel, P. A. (2013). The hazards of correcting myths about health care reform. Medical Care, 51(2), 127–132. https://doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0b013e318279486b

Oeldorf‐Hirsch, A., Schmierbach, M., Appelman, A., & Boyle, M. P. (2020). The ineffectiveness of fact‐checking labels on news memes and articles. Mass Communication and Society, 23(5), 682–704. https:// doi.org/10.1080/15205436.2020.1733613

Pennycook, G., Bear, A., Collins, E. T., & Rand, D. G. (2020). The implied truth effect: Attaching warnings to a subset of fake news headlines increases perceived accuracy of headlines without warnings. Management Science, 66(11), 4944–4957. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.2019.3478

Pennycook, G., & Rand, D. G. (2021). Research note: Examining false beliefs about voter fraud in the wake of the 2020 presidential election. Harvard Kennedy School (HKS) Misinformation Review, 2(1). https://doi.org/10.37016/mr-2020-51

Pew Research Center. (2021). Biden begins presidency with positive ratings; Trump departs with lowest-ever job mark [Report]. https://www.pewresearch.org/politics/2021/01/15/biden-begins-presidency-with-positive-ratings-trump-departs-with-lowest-ever-job-mark/

Porter, E., & Wood, T. J. (2024). Factual corrections: Concerns and current evidence. Current Opinion in Psychology, 55, Article 101715. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2023.101715

Ipsos. (2020, November 18). Most Americans agree Joe Biden is rightful winner of 2020 election: Latest Reuters/Ipsos poll shows most approve of how Joe Biden is handling his position of President-elect [Press release]. https://www.ipsos.com/sites/default/files/ct/news/documents/2020-11/topline_reuters_post_election_survey_11_18_2020.pdf

Ross, L., Lepper, M. R., & Hubbard, M. (1975). Perseverance in self-perception and social perception: Biased attributional processes in the debriefing paradigm. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 32(5), 880–892. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.32.5.880

Sharevski, F., Alsaadi, R., Jachim, P., & Pieroni, E. (2022). Misinformation warnings: Twitter’s soft moderation effects on COVID-19 vaccine belief echoes. Computers & Security, 114, Article 102577. https://doi.org/10.1016%2Fj.cose.2021.102577

Stagnaro, M. N., Druckman, J., Berinsky, A. J., Arechar, A. A., Willer, R., & Rand, D. G. (2024, April 24). Representativeness versus response quality: Assessing nine opt-in online survey samples. PsyArXiv. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/h9j2d

Taber, C. S., Cann, D., & Kucsova, S. (2009). The motivated processing of political arguments. Political Behavior, 31(2), 137–155. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-008-9075-8

Taber, C. S., & Lodge, M. (2006). Motivated skepticism in the evaluation of political beliefs. American Journal of Political Science, 50(3), 755–769. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5907.2006.00214.x

Tappin, B. M., Pennycook, G., & Rand, D. G. (2021). Rethinking the link between cognitive sophistication and politically motivated reasoning. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 150(6), 1095–1114. https://doi.org/10.1037/xge0000974

Thorson, E. (2016). Belief echoes: The persistent effects of corrected misinformation. Political Communication, 33(3), 460–480. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2015.1102187

Timm, J. C. (2020, November 4). With states still counting, Trump falsely claims he won. NBC News. https://www.nbcnews.com/politics/2020-election/10-states-still-counting-millions-votes-trump-falsely-claims-he-n1246336

Waggoner, P. D., Kennedy, R., & Clifford, S. (2019). Detecting fraud in online surveys by tracing, scoring, and visualizing IP addresses. Journal of Open Source Software, 4(37), 1285. https://doi.org/10.21105/joss.01285

Wicklund, R. A. (1974). Freedom and reactance. Lawrence Erlbaum.

Williams Kirkpatrick, A. (2021). The spread of fake science: Lexical concreteness, proximity, misinformation sharing, and the moderating role of subjective knowledge. Public Understanding of Science, 30(1), 55–74. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963662520966165

Wolfle, L. M. (1980). The enduring effects of education on verbal skills. Sociology of Education, 104–114. https://doi.org/10.2307/2112492

Wood, T., & Porter, E. (2019). The elusive backfire effect: Mass attitudes’ steadfast factual adherence. Political Behavior, 41(1), 135–163. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-018-9443-y

Zengerle, P., Landay, J., & Morgan, D. (2021, January 6). Under heavy guard, Congress back to work after Trump supporters storm U.S. Capitol. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-election/under-heavy-guard-congress-back-to-work-after-trump-supporters-storm-u-s-capitol-idUSKBN29B2PU

Ziemer, C.-T., & Rothmund, T. (2024). Psychological underpinnings of misinformation countermeasures: A systematic scoping review. Journal of Media Psychology: Theories, Methods, and Applications. https://doi.org/10.1027/1864-1105/a000407

Funding

This work was supported by the Eugene M. Lang Center for Civic and Social Responsibility at Swarthmore College.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics

This research received ethics approval from Swarthmore College’s Institutional Review Board.

Copyright

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided that the original author and source are properly credited.

Data Availability

All materials needed to replicate this study are available via the Harvard Dataverse: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/YWYS42 and the Open Science Framework: https://osf.io/vnft5/?view_only=567fea549d6b49c2ab9cc6b68ed97b3a