(RNS) — In the 1995 novel that inspired the musical and film, the Wicked Witch of the West is a green-skinned child of a minister exploited for his missionary endeavors.

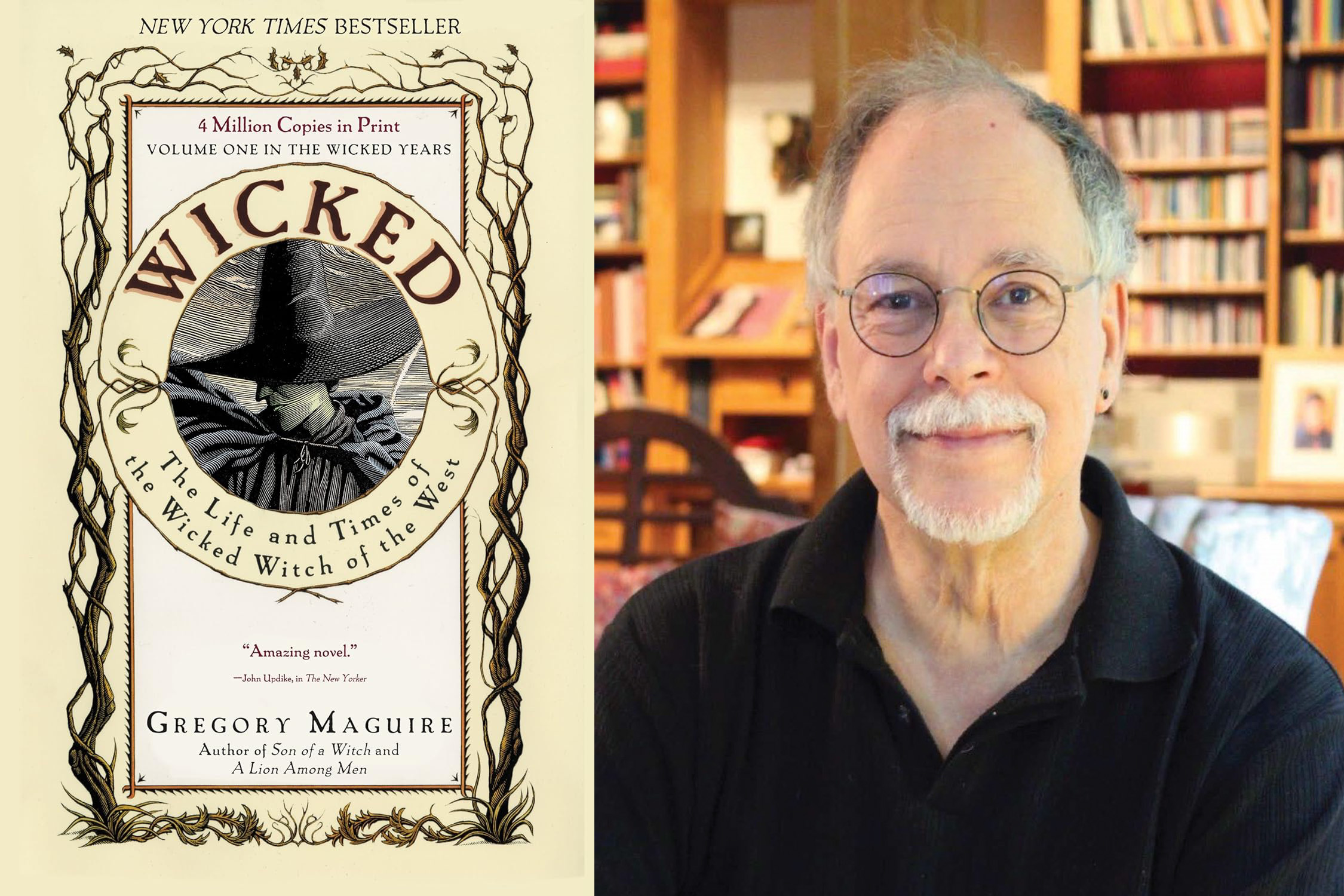

“Wicked” and author Gregory Maguire. (Courtesy images)

Kathryn Post

November 19, 2024

(RNS) — Before “Wicked” was a blockbuster film and a hit Broadway musical, it was a 1995 novel rife with dark twists and a whole lot of religion.

Gregory Maguire’s origin story for the Wicked Witch of the West introduces readers to Elphaba, the green-skinned child of a minister who exploits her for his missionary endeavors. Set in the land of Oz, introduced in L. Frank Baum’s 1900 classic children’s series and brought to life in MGM’s “The Wizard of Oz,” Maguire’s over-500-page-long book fleshes out the religious, political and personal clashes that shape the familiar characters and set the stage for Dorothy’s arrival.

Named after a saint, Elphaba is an atheist who believes she has no soul, yet spends several years living in a convent and longing for forgiveness. Though the musical removes the novel’s more explicit religious references, the questions at the heart of the story — What differentiates good from evil? Where does wickedness come from? — are central in all its adaptations.

Ahead of the film’s debut in theaters on Nov. 22, RNS spoke to “Wicked” author Gregory Maguire about his religious upbringing, Elphaba’s search for a soul and why nuns, saints and witches might not be all that different. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Were you raised in a religious context, and did that shape your approach to religion in “Wicked”?

I was raised in the Roman Catholic tradition in an Irish Catholic neighborhood, and I continue to define myself as a practicing Roman Catholic, though I have to practice pretty hard at it. But religion was very important to me as a young person. I came close to considering going into seminary in my early 20s, and I took the fact of religion in people’s lives, or its absence, as a very serious part of how individuals and cultures identify themselves. When I wrote about Oz, I wanted it to be more like our world, which meant I had to import religion there. Religion is one of the few things that is absent in any portrait of Oz at all, with the exception of the very general founding myth of the fairy queen Lurline.

What are the faith systems you’ve imported into Oz?

Lurlinism is a kind of paganism, a kind of foundational myth. It is ancient, sentimental, and in the world of my story, it is the peasants who adhere most strongly to it. Unionism is that more established faith found more in cities. It has a kind of allegiance with Christianity in that it has churches, basilicas and bishops, but there is no savior. The God is unnamed, influential and mysterious. In this way, it takes some tropes from faith traditions that favor a more amorphous spirit head. That is both a kind of Protestant attitude — the crashing of statues and smashing of windows, etc. — but it also has a bit in common with Islam, which disallows the depiction of Allah, except through the writing of Allah’s name. So Unionism is an odd amalgam of that instinct in certain religions to try to keep the image of God open and therefore more accessible. Interestingly enough, of course, it is also less accessible if you can’t hang an image on it.

Pleasure Faithism is, in my mind, a kind of Carnival picture of God. It puts a higher premium on spectacle. It involves the Greek idea of theater, coming together for a kind of epiphany and catharsis. And finally, there’s Tiktokism, which comes closest to a certain way that we live now in the West. A Tiktokist is the kind of person who won’t go into a church and turn off their phone. Their allegiance is to the stimulation, to the connection and to the appliance. While we don’t have cellphones in my Oz, there is a kind of reverence for that aspect of that moment in the Industrial Revolution which Oz seems to be going through. Tiktokism is a more dangerous shifting of the devotional impulse away from the question of creation and toward the questions of utility.

How might Elphaba’s early exposure to Unionism have shaped her worldview?

“Elphie” by Gregory Maguire. (Courtesy image)

I go into this with a little more depth in my novel coming out in about four months, “Elphie.” I go back to those years in Elphaba’s life that run between the age of about 2 and about 16. In this book, Elphaba is seen being courted by her father to round up possible communicants in his missionary work, to be the lure. And one of the ways she does that is by singing. Her ability to sing was a crucial part of my humanizing her. A person with a voice has beauty, and her father exploited it. She allowed herself to be exploited because she wanted his love. But religion, if it doesn’t make her into a deeply moral person, at least brings her into contact with people who are not like her, and that is what community is for. It’s to make us empathize with people who are not us.

How and why does Elphaba grapple with the idea of a soul?

To become an atheist, I think, you have to think about God. It’s not a default position. Raised in a religious environment, Elphaba has to grapple with what she believes, and if the way that she’s made is evidence of her having been rejected by a creator, or embraced by a creator. I think all young people do that, especially as they come to understand their own frailties, and the fact that they can never be as good as their religious training teaches they should be. In that juxtaposition of the ideal and the actual, we find the first exposure to possible apostasy, and have to grapple with it. And that’s what she does. She has not been treated with many instances of love in her childhood, and so it’s hard for her to project a universal love as a Godhead might be said to have for her. Nonetheless, she is smart enough that she can think, well, maybe the soul exists, even if I haven’t experienced it in my own life and times.

In the characters of Elphaba, Glinda and Nessarose, we see the interplay between sainthood and witchcraft. How might the novel’s approach to religion complicate otherwise rigid definitions of good and evil?

If you isolate the characteristics many cultures identify with the witch and the wise woman, often they were characteristics that are identical. Wisdom about the application of herbs, to the pre-rationalist mind, could be magic or medicine. I’m taking my lead from L. Frank Baum, who created four witches in Oz, two that were good and two who were bad. His mother-in-law, the feminist Matilda Joslyn Gage, wrote scathingly about how women were opposed by Christianity, and how they were not given the proper valuation. Now, L. Frank Baum didn’t talk about Christianity in any of his books, but the fact the power of women could be both feared and appreciated in the same book, I think, expressed a growing sentiment that brought us into the 20th century, toward the suffragette movement.

I was taught up until the end of 12th grade by Catholic nuns. I was pre-Vatican II, and my first teachers for the first four years, you might as well call them witches. We were tiny. They were tall, and had long black skirts that went to the floor, black shoes and black veils and white wimples and white bibs. They were simultaneously good and all-powerful, and were self-imposed paupers living in community. They exerted on children the highest moral authority. I was raised by strong women, by nuns and librarians and my stepmother. I have great respect for those women.

Can you talk about some of the more subtle ways your original novel’s spiritual themes are integrated into the musical?

I don’t think they are, with a single exception. Religion teaches us to be collaborative and communal (by churchgoing and respecting others who may not be like us), but also to be independent, and in possession of our own moral guidance system. We’re meant to own the behavior of our own souls, and we’re meant to belong to a community and make it better. In “Wicked” the musical, that same crisis between the impulse to be a citizen and care about society, and the impulse to be an individual and not anesthetize yourself away from your own individuality because it offends society, does exist. I wouldn’t say that is only a religious impulse, but it’s one of the things that religion does.

One of the things about “Wicked” you see in my book, that you don’t see in L. Frank Baum, in MGM, or in the wonderful musical and movie, is that the culture is really made up of very different populations. In my books, there are several languages spoken in Oz, a number of cultures. In that setting, a character who has no place in the world, Elphaba, might recognize we all feel somewhat illegitimate in the breadth of human experience, and we all must get on with it anyway. That’s not exactly a religious instinct, and Elphaba is no Jesus figure, but I do think she is like all of us who ask ourselves, how can I be a Samaritan? How can I lean toward the humanity of somebody who looks nothing like me, doesn’t speak like me, doesn’t behave like me, doesn’t pray like me, and maybe wishes even my demise and destruction? What does my belief system require me to do? And where can I find the courage to do it?