BOOKS

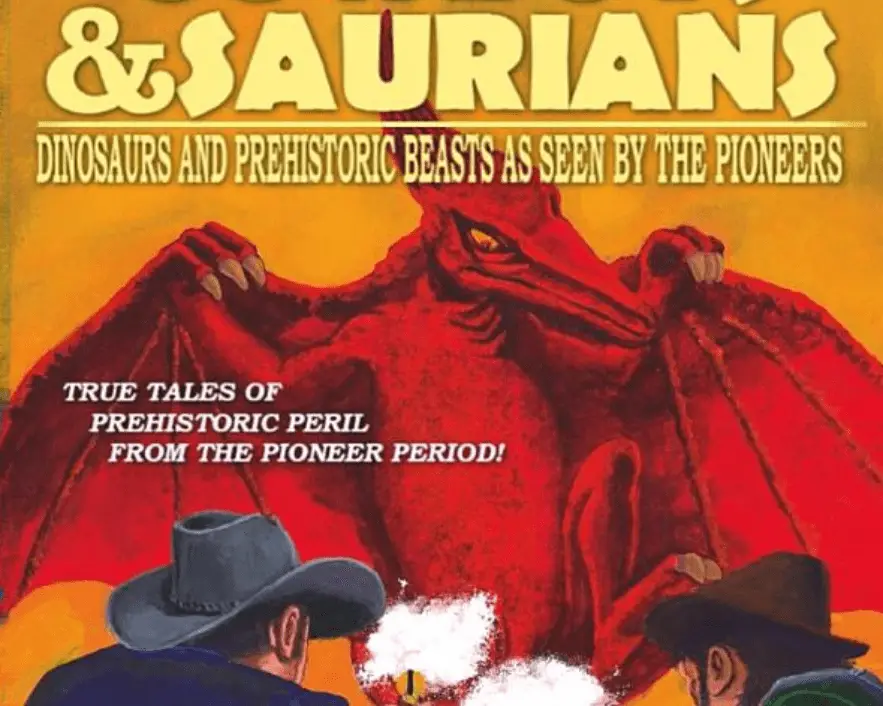

‘Cowboys & Saurians: Dinosaurs and Prehistoric Beasts as Seen by the Pioneers’ – book review

Dinosaurs in the Old West. REAL accounts?

ByJustin Mullis on February 15, 2020

In his landmark 1998 study of the role played by dinosaurs in American culture, The Last Dinosaur Book (U. of Chicago Press), scholar W.J.T. Mitchell observed that “… Dinosaurs rightly belong in the picture with cowboys – and Indians and buffalo and outlaws and railroads and cavalry – in short, in the world of the American frontier, understood as a blend of fact and fantasy, a real place and a Hollywood invention.”

Though Mitchell’s observation wasn’t concerning alleged real-life accounts of dinosaurs and other similar creatures sighted on the North American frontier during the start of the 20th century, I imagine that author John LeMay would no doubt concur with this sentiment given that his latest book, Cowboys & Saurians: Dinosaurs and Prehistoric Beasts As Seen By The Pioneers (Bicep Books, 2019), is exactly that, a collection of over 27 supposed historical reports of Mesozoic monsters seen just west of the Mississippi between the years 1870 and 1914, accompanied by 85 black and white illustrations.

I’ve known John for a couple years and was a contributor to his book on King Kong, and co-chaired a panel on Hammer and Toho’s unmade Loch Ness Monster movie with him at G-Fest in 2019. John made me promise that despite our friendship I wouldn’t go easy on him in this review, and I won’t. For Cowboys & Saurians, he combed through historical newspaper archives to uncover accounts of supposed encounters with dinosaurs, pterosaurs, various Mesozoic marine reptiles, and other often far stranger scaly beasts on the American frontier. His approach to this subject matter is critical but not “capital-S” skeptical.

LeMay combed through historical newspaper archives to uncover encounters with dinosaurs, pterosaurs, and Mesozoic marine reptiles.

LeMay notes early on that most, if not all, of these stories are likely hoaxes whipped up by bored newspaper men. Such tall-tales, at least when concerning reptilian monsters, were often sold as “snaik” or “snaix” stories – a deliberate misspelling of “snake” – as a way of tipping off readers to their dubious provenance. When an article mentions a specific town or names specific individuals, LeMay has done his best to confirm if these locations and people were real.

Undoubtedly the strongest aspect of Cowboys & Saurians is LeMay’s decision to reprint the original newspaper stories in their entirety. This way readers can examine the original accounts for themselves, rather than being dependent on an author’s retelling of events, a common pitfall in popular cryptozoological books, in which primary source accounts are often refined and/or embellished to make a particular case sound more dramatic or convincing.

The book opens with what may be the greatest “snaik” story of all-time, the Tombstone Pterodactyl. According to an article published in the April 26, 1890 edition of Tombstone, Arizona’s Epitaph newspaper, two anonymous ranchers encountered and killed a “monster, resembling a huge alligator with an extremely long tail,” and a 160-foot wingspan. LeMay is careful to note that no known species of pterosaur had such a massive wingspan, another point in favor of his research. He also posits that the story was likely invented to try and help generate interest in the town of Tombstone, which was in dire economic straits at the time and looking for an influx of tourism dollars.

The Tombstone Pterodactyl story ultimately disappeared, only to be resurrected decades later in letters columns of the popular paranormal periodicals Fate and Strange Magazine, where a new element was added — the claim that a photograph of the dead pterodactyl existed. Noted Fortean researchers Ivan Sanderson and John Keel claimed to have seen the photograph, along with scores of others, but for some reason no one could ever produce a copy.

Here we run into one of LeMay’s two major pitfalls with this book, a willingness to entertain baseless paranormal conjectures as possible answers to cryptozoological mysteries. He ends his otherwise strong chapter on the Tombstone Pterodactyl by asking if the Mandela Effects – a ludicrous conspiracy theory that I have neither the patience nor word count to explain – could be responsible for the missing pterosaur photo.

Saurians‘ other major shortcoming concerns the book’s secondary sources, which are composed almost entirely of literature by popular cryptozoologists. This includes veterans like Loren Coleman, Roy Mackal, Karl Shuker, and Mark Hall, as well as lesser luminaries like Jason Offutt and David Weatherly, and even a few outright frauds, like young-earth creationist Jonathan Whitcomb. The only academic text dealing with the subject repeatedly cited throughout Cowboys & Saurians is Stanford University folklorist Adrienne Mayor’s 2005 book, Fossil Legends of the First Americans.

Had LeMay conducted a more in-depth survey of the existing literature on his subject, he may have discovered such interesting and useful scholarly works as Reeve and Wagenen’s Between Pulpit and Pew: The Supernatural World in Mormon History and Folklore (Utah State University Press, 2011), which would have aided greatly in what was nevertheless one of my favorite entries, on the Bear Lake Monster of Utah, a beast with an interesting connection to that state’s iconic religious denizens.

In addition to these previously documented accounts, some of the book’s more obscure stories are especially interesting given their parallels with some famous cryptid sightings of the 20th century. These include Ohio’s Creature from Crosswicks Creek, seen in May of 1882, which bears an uncanny resemblance to South Carolina’s Lizard Man of Scape Ore Swamp of the late 1980s, as well as the Van Meter Monster that terrorized a small Iowa town in the fall of 1903, which shares a family resemblance to West Virginia’s Mothman of the 1960s.

Whether skeptics or believers, Cowboys & Saurians should prove a major draw for cryptozoology aficionados, as LeyMay has compiled a veritable treasure trove of information here on what is an otherwise largely unremarked upon phenomena.

Every February, to help celebrate Darwin Day, the Science section of AIPT cranks up the critical thinking for SKEPTICISM MONTH! Skepticism is an approach to evaluating claims that emphasizes evidence and applies the tools of science. All month we’ll be highlighting skepticism in pop culture and skepticism of pop culture.

AIPT Science is co-presented by AIPT and the New York City Skeptics.

report this ad

report this adIn this article:

Don't Miss:

History Channel’s ‘Project Blue Book’ goes completely over the edge — ‘Area 51’ pushes a case that never was

No comments:

Post a Comment