20 amazing women in science and math

Brenda Milner (born 1918)

Sometimes called the "founder of neuropsychology," Brenda Milner has made groundbreaking discoveries about the human brain, memory and learning.

Milner is best known for her work with "Patient H.M.," a man who lost the ability to form new memories after undergoing brain surgery for epilepsy. Through repeated studies in the 1950s, Milner found that Patient H.M. could learn new tasks, even if he had no memory of doing it. This led to the discovery that there are multiple types of memory systems in the brain, according to the Canadian Association for Neuroscience. Milner's work played a major role in the scientific understanding of the functions of different areas of the brain, such as the role of the hippocampus and frontal lobes in memory and how the two brain hemispheres interact.

Her work continues to this day. At age 101, Milner is still a professor in the department of neurology and neurosurgery at McGill University in Montreal, according to the Montreal Gazette.Mary Anning (1799-1847)

The children's tongue twister "she sells seashells by the seashore" was allegedly inspired by real-life seaside paleontologist Mary Anning. She was born and raised near the cliffs of Lyme Regis in southwestern England; the rocky outcrops near her home were teeming with Jurassic fossils.

She taught herself to recognize, excavate and prepare these relics when the field of paleontology was in its infancy — and closed to women. Anning provided London paleontologists with their first glimpse of an ichthyosaur, a large marine reptile that lived alongside dinosaurs, in fossils that she discovered when she was no more than 12 years old, the University of California Museum of Paleontology (UCMP) in Berkeley, California, reported. She also found the first fossil of a plesiosaur (another extinct marine reptile).

Ada Lovelace (1815-1852)

Ada Lovelace was a 19th century self-taught mathematician and is thought of by some as the "world's first computer programmer."

Lovelace grew up fascinated by math and machinery. At age 17, she met English mathematician Charles Babbage at an event where he was demonstrating a prototype for a precursor to his "analytical engine," the world's first computer. Fascinated, Lovelace decided to learn everything she could about the machine.

In 1837, Lovelace translated a paper written about the analytical engine from French. Alongside her translation, she published her own detailed notes about the machine. The notes, which were longer than the translation itself, included a formula she created for calculating Bernoulli numbers. Some say that this formula can be thought of as the first computer program ever written, according to a previous Live Science report.

Lovelace is now a major symbol for women in science and engineering. Her day is celebrated on the second Tuesday of every October.

Rachel Carson (1907-1964)

Rachel Carson was an American biologist, conservationist and science writer. She's best known for her book "Silent Spring" (Houghton Mifflin, 1962), which describes the harmful effects of pesticides on the environment. The book eventually led to the nationwide ban of DDT and other harmful pesticides, according to the National Women's History Museum.

Carson studied at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution in Massachusetts and received her master's degree in zoology from Johns Hopkins University in 1932. In 1936, Carson became the second woman hired by the U.S. Bureau of Fisheries (which later became the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service), where she worked as an aquatic biologist, according to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Her research allowed her to visit many waterways around the Chesapeake Bay region, where she first began to document the effects of pesticides on fish and wildlife.

Carson was a talented science writer, and the Fish and Wildlife Service eventually made her the editor in chief of all its publications. After the success of her first two books on marine life, "Under the Sea Wind" (Simon and Schuster, 1941) and "The Sea Around Us" (Oxford, 1951), Carson resigned from the Fish and Wildlife Service to focus more on writing.

With the help of two other former employees from the Fish and Wildlife Service, Carson spent years studying the effects of pesticides on the environment across the United States and Europe. She summarized her findings in her fourth book, "Silent Spring," which spurred enormous controversy. The pesticide industry tried to discredit Carson, but the U.S. government ordered a complete review of its pesticide policy, and as a result, banned DDT. Carson has since been credited with inspiring Americans to consider the environment.

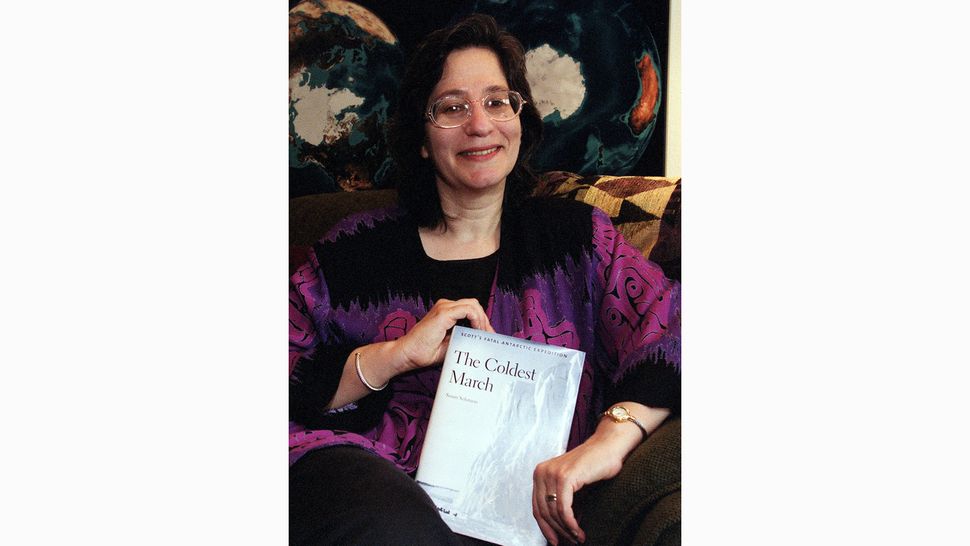

Susan Solomon (born 1956)

Susan Solomon is an atmospheric chemist, author, and professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology who for decades worked at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). During her time at NOAA, she was the first to propose, with input from her colleagues, that chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) were responsible for the Antarctic hole in the ozone layer.

She led a team in 1986 and 1987 to McMurdo Sound on the southern continent, where the researchers gathered evidence that the chemicals, released by aerosols and other consumer products, interacted with ultraviolet light to remove ozone from the atmosphere.

This led to the U.N. Montreal Protocol, which became effective in 1989, banning CFCs worldwide. It's considered one of the most successful environmental projects in history, and the hole in the ozone layer has shrunk considerably since the protocol's adoption.

Maryam Mirzakhani (1977-2017)

Maryam Mirzakhani was a mathematician known for solving hard, abstract problems in the geometry of curved spaces. She was born in Tehran, Iran, and did her most important work as a professor at Stanford University, between 2009 and 2014.

Her work helped explain the nature of geodesics, straight lines across curved surfaces. It had practical applications for understanding the behavior of earthquakes and turned up answers to long-standing mysteries in the field.

In 2014 she became the first — and still only — woman to win the Fields Medal, the most prestigious prize in mathematics. Each year, the Fields Medal is awarded to a handful of mathematicians under the age of 40 at the International Mathematical Union's International Congress of Mathematicians.

Mirzakhani received her medal one year after she was diagnosed with breast cancer, in 2013. The cancer killed her on July 14, 2017, at age 40. Mirzakhani continues to influence her field, even after her death; in 2019, her colleague Alex Eskin won the $3 million Breakthrough Prize in mathematics for revolutionary work he did with Mirzakhani on the "magic wand theorem." Later that year, the Breakthrough Prize endowed a new award in Mirzakhani's honor, which would go to promising, young women mathematicians.

SEE THE OTHER 14 HERE

No comments:

Post a Comment