New book shows how ancient Greek writing helps us understand today's environmental crises

by Jodi Heckel, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

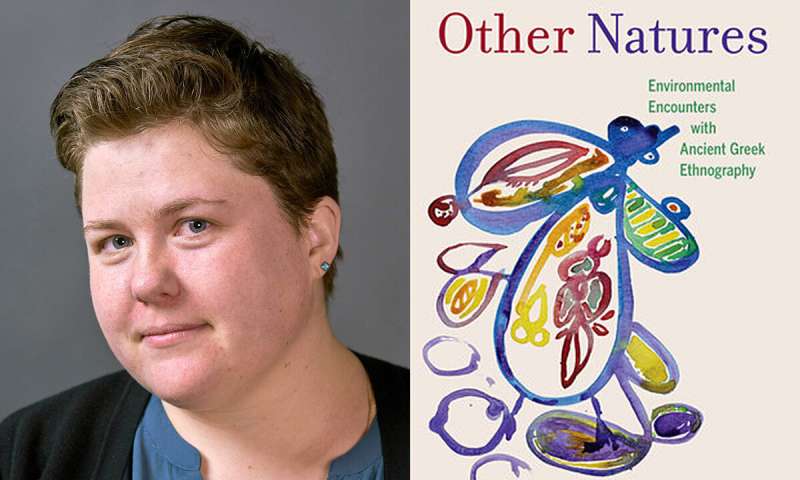

Credit: University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

The way ancient Greeks thought about the natural environment and their relationship to it is relevant to how we respond to environmental crises today. In her new book, "Other Natures," Clara Bosak-Schroeder, a classics professor at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, looks at how the ethnographies written by ancient Greeks reveal how they explored ideas about consumption and their use of natural resources.

The book focuses on two Greek writers, Herodotus, writing in the 5th century B.C., and Diodorus, writing a few centuries later, and considers their work from the perspective of concern about our current climate emergency. Their ethnographies were the travel writing of their day, describing the habits and customs of people in other places—Africa, India and parts of the Middle East—and how they used natural resources.

"What I found was these Greek and Roman writers weren't doing this kind of reflection on natural resources when they were writing about their own homelands," Bosak-Schroeder said.

One of their major concerns was diet and the connection between diet and health.

"When they looked at other people, they saw them eating very different types of foods, and they were curious about how those foods could promote health and the ways they might be superior to the Greek diet," Bosak-Schroeder said.

Their writing also was a window into systems of consumption and how people are involved in growing food and killing animals, she said. Herodotus and Diodorus were particularly interested in how people related to animals, and their stories reflect that. Diodorus wrote about an African community with a close relationship to seals, where humans and seals hunted together and shared childcare.

While the story is fabricated, "it helps to see that the writers were curious about boundaries between humans and animals, and whether it is possible to have some sort of shared community," Bosak-Schroeder said. "I saw the Greek writers experimenting with how to live with other species, perhaps in more productive ways."

Diodorus also wrote about ancient Egyptians who honored their sacred animals by giving them rich, refined foods—a way to worship the animals with the side effect that Egyptians stayed healthier by not eating that food themselves.

"The idea underlying the story is that we can live richer, fuller lives if we take the well-being of other species into account," Bosak-Schroeder said. "The Greek writers were not environmentalists and not interested in animal welfare for its own sake, but they saw humans depending on other species. It was a pragmatic approach to their own well-being that was connected to other beings on the planet."

They also expressed concerns about consumption, she said.

"Even though they weren't living in a global environmental crisis the way we are, they still seem to be anxious about their consumption of luxury items and whether they should be importing things from other places. They didn't cast those questions exactly in environmental terms, but they saw that their choices could have bigger, unintended consequences," she said.

The writers focused on the role of women and their perspectives on the world as something different and valuable, with insights into what is possible. Diodorus wrote about an Assyrian queen who invaded India, then realized she could not conquer the country because Indians had war elephants. She had huge elephant puppets made from wooden frameworks covered in ox skins, and they were drawn up to the battle lines to fool the Indians.

That idea of listening to diverse viewpoints translates to looking for solutions to climate change, as well as holding leaders accountable for finding a centralized approach to big problems, Bosak-Schroeder said.

"That's a powerful idea right now when a lot of environmental work is being done by people in marginalized communities," she said. "The parts of the world already experiencing climate change have this perspective that we in richer, more industrialized nations really need to listen to."

The final part of "Other Natures" moves from ancient Greece to modern museums of natural history and looks at the way people are educated about environmental issues when they go to museums. Bosak-Schroeder studied exhibits at the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago and other natural history museums throughout the country. She suggests they can take a cue from the ancient writers in how they display their collections of artifacts and plant and animal specimens by integrating their stories.

"Museums can do more to show how humans relate to other species and are interdependent with them, and they can do that in the way they put collections together," she said. "They have really great practices that can help people understand our climate emergency."

The way ancient Greeks thought about the natural environment and their relationship to it is relevant to how we respond to environmental crises today. In her new book, "Other Natures," Clara Bosak-Schroeder, a classics professor at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, looks at how the ethnographies written by ancient Greeks reveal how they explored ideas about consumption and their use of natural resources.

The book focuses on two Greek writers, Herodotus, writing in the 5th century B.C., and Diodorus, writing a few centuries later, and considers their work from the perspective of concern about our current climate emergency. Their ethnographies were the travel writing of their day, describing the habits and customs of people in other places—Africa, India and parts of the Middle East—and how they used natural resources.

"What I found was these Greek and Roman writers weren't doing this kind of reflection on natural resources when they were writing about their own homelands," Bosak-Schroeder said.

One of their major concerns was diet and the connection between diet and health.

"When they looked at other people, they saw them eating very different types of foods, and they were curious about how those foods could promote health and the ways they might be superior to the Greek diet," Bosak-Schroeder said.

Their writing also was a window into systems of consumption and how people are involved in growing food and killing animals, she said. Herodotus and Diodorus were particularly interested in how people related to animals, and their stories reflect that. Diodorus wrote about an African community with a close relationship to seals, where humans and seals hunted together and shared childcare.

While the story is fabricated, "it helps to see that the writers were curious about boundaries between humans and animals, and whether it is possible to have some sort of shared community," Bosak-Schroeder said. "I saw the Greek writers experimenting with how to live with other species, perhaps in more productive ways."

Diodorus also wrote about ancient Egyptians who honored their sacred animals by giving them rich, refined foods—a way to worship the animals with the side effect that Egyptians stayed healthier by not eating that food themselves.

"The idea underlying the story is that we can live richer, fuller lives if we take the well-being of other species into account," Bosak-Schroeder said. "The Greek writers were not environmentalists and not interested in animal welfare for its own sake, but they saw humans depending on other species. It was a pragmatic approach to their own well-being that was connected to other beings on the planet."

They also expressed concerns about consumption, she said.

"Even though they weren't living in a global environmental crisis the way we are, they still seem to be anxious about their consumption of luxury items and whether they should be importing things from other places. They didn't cast those questions exactly in environmental terms, but they saw that their choices could have bigger, unintended consequences," she said.

The writers focused on the role of women and their perspectives on the world as something different and valuable, with insights into what is possible. Diodorus wrote about an Assyrian queen who invaded India, then realized she could not conquer the country because Indians had war elephants. She had huge elephant puppets made from wooden frameworks covered in ox skins, and they were drawn up to the battle lines to fool the Indians.

That idea of listening to diverse viewpoints translates to looking for solutions to climate change, as well as holding leaders accountable for finding a centralized approach to big problems, Bosak-Schroeder said.

"That's a powerful idea right now when a lot of environmental work is being done by people in marginalized communities," she said. "The parts of the world already experiencing climate change have this perspective that we in richer, more industrialized nations really need to listen to."

The final part of "Other Natures" moves from ancient Greece to modern museums of natural history and looks at the way people are educated about environmental issues when they go to museums. Bosak-Schroeder studied exhibits at the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago and other natural history museums throughout the country. She suggests they can take a cue from the ancient writers in how they display their collections of artifacts and plant and animal specimens by integrating their stories.

"Museums can do more to show how humans relate to other species and are interdependent with them, and they can do that in the way they put collections together," she said. "They have really great practices that can help people understand our climate emergency."

Explore furtherPlant specimens provide powerful data about life in the A

No comments:

Post a Comment