TOMMOROWS NEWS TODAY

India's infertility war: Exposure to chemicals lowers sperm count, egg quality

By Pooja Biraia Jaiswal May 23, 2021

By Pooja Biraia Jaiswal May 23, 2021

THE WEEK MAGAZINE

Illustration Job P.K.

Until about a decade ago, weekdays at the Agatsya Sperm Bank in Rajkot saw men, aged between 20 to 30 years, queue up outside the facility. A quick screening, and the young, athletic, qualified, English-speaking men among them would be picked out. For, it would be certain that they would have sufficient volumes of “healthy swimmers”, enough to be transported to clinics across Gujarat for assisted reproduction. At the time, 70 per cent of the semen samples received were accepted and marked “ready for use”. But that was then, when the Indian sperm was healthy and in abundance.

Infertility is on an alarming rise in India, with the country estimated to be contributing to nearly 25-30 per cent of all couples diagnosed with it the world over. —Dr Neeta Singh, senior consultant and professor,

Until about a decade ago, weekdays at the Agatsya Sperm Bank in Rajkot saw men, aged between 20 to 30 years, queue up outside the facility. A quick screening, and the young, athletic, qualified, English-speaking men among them would be picked out. For, it would be certain that they would have sufficient volumes of “healthy swimmers”, enough to be transported to clinics across Gujarat for assisted reproduction. At the time, 70 per cent of the semen samples received were accepted and marked “ready for use”. But that was then, when the Indian sperm was healthy and in abundance.

Infertility is on an alarming rise in India, with the country estimated to be contributing to nearly 25-30 per cent of all couples diagnosed with it the world over. —Dr Neeta Singh, senior consultant and professor,

AIIMSDEHP, a plasticiser, can migrate from packaging into fatty food, and leaching of plasticisers into food from packaging is the potential danger of this era. —Srinivasan K., Indian Institute of Food Processing Technology, Thanjavur

We are observing a very lifestyle-related infertility that stems from increasing age, late marriages and the kind of chemicals and pollutants we are exposed to. —Dr Aditi Dani, fertility consultant at Masina Hospital, Mumbai

In humans, cross-sectional data suggests that BPA concentrations are higher in women with PCOS than in reproductively healthy women. —Alka Dubey, programme coordinator, chemical and health, Toxics Lin

Today, it is the opposite. “Now, 70 per cent of the samples we receive are rejected,” said Dr Yogesh Choksi, a microbiologist who started the facility in 1997. His is the oldest registered cryobank in Gujarat. “Even as the number of donors has, by and large, remained steady, the quality and volume of semen has fallen down sharply,” he said. When Choksi started the bank, he recalls that any given semen sample would range between 3.5ml and 4ml with a sperm count of 80-100 million per millilitre, which was considered normal at the time. That way, it was possible to fill five vials with a single semen sample. But now, “a single semen sample measures between 1ml and 1.5ml and the sperm count remains as low as 15-20mpm,” he said. “We barely get one full vial from a single sample.”

Shocking, right? But it is a reality that has been staring us in the face all along. And combined with a decline in testosterone levels in Indian men, it has consequently resulted in the rise in infertility cases.

SWIMMERS TAKE A DIP

In 2017, researchers in the US concluded that the sperm count of an average man in western countries had fallen by 59 per cent between 1973 and 2011. Next year, researchers at the CSIR-Central Drug Research Institute in Lucknow undertook a similar study, analysing just how steep and continuing the slump was among 6,000 fertile and 7,000 infertile Indian men from 1979 to 2016. The study found that semen parameters in Indian men—including the sperm count, volume and movement—had declined with time and the deterioration was quantitatively higher in the infertile group, with the mean semen volume as low as 0.77ml and the sperm count at 29mpm.

Said Rajender Singh, principal scientist (endocrinology) at CSIR-CDRI: “In the same period of study, if we do not distinguish between fertile and infertile men and take them as one cohort, we, in India, have witnessed a decline of 26 per cent in the overall sperm count, from 87mpm in 1979 to 64mpm in 2016.” Yet, what is concerning is not just that the count and quality are declining, but that they are declining below the World Health Organization’s normal reference range of 15mpm. Any value beyond this renders a man infertile. And, clinicians in India are witnessing a large number of men coming to them with complaints of infertility due to a sperm count that “at times falls down to extremely low (oligospermia) or even zero (azoospermia),” said Dr Aditi Dani, fertility consultant at Mumbai’s Masina Hospital.

‘EGGS’ISTENTIAL CRISIS

But it is not just men. The ability to conceive a child naturally has taken a hit in both men and women equally. “There is no doubt that an ever increasing number of girls in India are experiencing early puberty,” said Dani, “while women are losing good quality eggs at younger ages than their mothers or grandmothers did.”

We are observing a very lifestyle-related infertility that stems from increasing age, late marriages and the kind of chemicals and pollutants we are exposed to. —Dr Aditi Dani, fertility consultant at Masina Hospital, Mumbai

In humans, cross-sectional data suggests that BPA concentrations are higher in women with PCOS than in reproductively healthy women. —Alka Dubey, programme coordinator, chemical and health, Toxics Lin

Today, it is the opposite. “Now, 70 per cent of the samples we receive are rejected,” said Dr Yogesh Choksi, a microbiologist who started the facility in 1997. His is the oldest registered cryobank in Gujarat. “Even as the number of donors has, by and large, remained steady, the quality and volume of semen has fallen down sharply,” he said. When Choksi started the bank, he recalls that any given semen sample would range between 3.5ml and 4ml with a sperm count of 80-100 million per millilitre, which was considered normal at the time. That way, it was possible to fill five vials with a single semen sample. But now, “a single semen sample measures between 1ml and 1.5ml and the sperm count remains as low as 15-20mpm,” he said. “We barely get one full vial from a single sample.”

Shocking, right? But it is a reality that has been staring us in the face all along. And combined with a decline in testosterone levels in Indian men, it has consequently resulted in the rise in infertility cases.

SWIMMERS TAKE A DIP

In 2017, researchers in the US concluded that the sperm count of an average man in western countries had fallen by 59 per cent between 1973 and 2011. Next year, researchers at the CSIR-Central Drug Research Institute in Lucknow undertook a similar study, analysing just how steep and continuing the slump was among 6,000 fertile and 7,000 infertile Indian men from 1979 to 2016. The study found that semen parameters in Indian men—including the sperm count, volume and movement—had declined with time and the deterioration was quantitatively higher in the infertile group, with the mean semen volume as low as 0.77ml and the sperm count at 29mpm.

Said Rajender Singh, principal scientist (endocrinology) at CSIR-CDRI: “In the same period of study, if we do not distinguish between fertile and infertile men and take them as one cohort, we, in India, have witnessed a decline of 26 per cent in the overall sperm count, from 87mpm in 1979 to 64mpm in 2016.” Yet, what is concerning is not just that the count and quality are declining, but that they are declining below the World Health Organization’s normal reference range of 15mpm. Any value beyond this renders a man infertile. And, clinicians in India are witnessing a large number of men coming to them with complaints of infertility due to a sperm count that “at times falls down to extremely low (oligospermia) or even zero (azoospermia),” said Dr Aditi Dani, fertility consultant at Mumbai’s Masina Hospital.

‘EGGS’ISTENTIAL CRISIS

But it is not just men. The ability to conceive a child naturally has taken a hit in both men and women equally. “There is no doubt that an ever increasing number of girls in India are experiencing early puberty,” said Dani, “while women are losing good quality eggs at younger ages than their mothers or grandmothers did.”

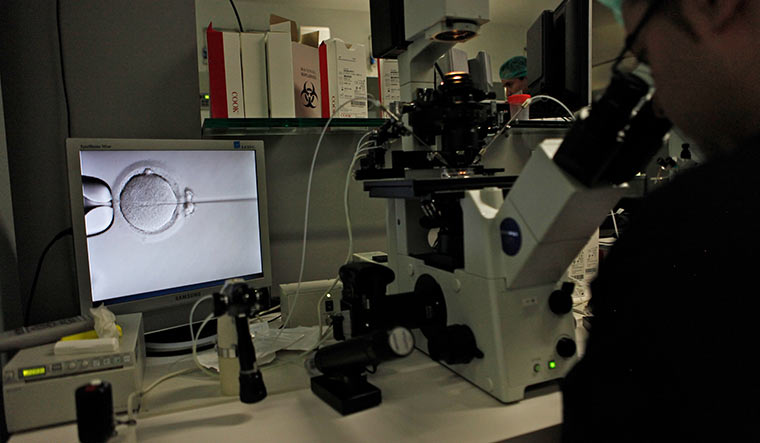

Trouble shooter: An in vitro fertilisation facility | Getty Images

India, the second most populous country after China, finds itself at the centre of a paradoxical situation: an ever-mushrooming population on one hand and a dramatic year-on-year decline in its fertility rate on the other. A fertility rate of about 2.2—a couple having two children—is generally considered the replacement level, the rate at which the population would hold steady. When the fertility rate dips below this number, the population is expected to decline. As per the National Health Profile 2018, the total fertility rate fell below two children per woman in 12 states, and just about reached replacement levels in nine others. While there is no doubt that family planning has been the chief guiding force behind this, experts believe that the rising incidence of infertility is also to blame. “Infertility is on an alarming rise in India, with the country estimated to be contributing to nearly 25-30 per cent of all couples diagnosed with it the world over,” said Dr Neeta Singh, senior consultant and professor, division of reproductive medicine at the All India Institute of Medical Sciences. According to the Indian Society of Assisted Reproduction, one in six couples suffers from infertility, amounting to 27.5 million infertile couples trying for conception. “You can gauge the magnitude of the problem from the patient load at the AIIMS ART Centre,” said Singh. “As per the medical records for 2018-2019, nearly 15 lakh patients consulted the outpatient department, of which 5,468 patients underwent ART (assisted reproductive technology) treatment.”

ABC OF EDCs

And while the reasons vary—age can be a contributing factor, as can lifestyle issues like stress and obesity—scientists and researchers are more worried about what are called endocrine disrupting chemicals. EDCs represent a broad class of chemicals such as organochlorinated and organophosphate pesticides—used in agriculture and mosquito control—and industrial chemicals, plastics and plasticisers (used to soften plastics) and fuels. They are ubiquitous; EDCs can be found in food wraps and plastic water bottles, even in the perfume you wear, the tap water you drink and cook with, and the air you breathe. And, it is their unrestricted use that is harming our ability to have natural pregnancies.

“Their impact becomes even more magnified and frightening for India, as we are witnessing an ever-growing consumerist culture and have relatively easy regulations,” said Dr Kamlesh Sarkar, director, ICMR-National Institute of Occupational Health, Ahmedabad.

EDCs essentially interfere with and disrupt the body’s endocrine system that monitors the hormonal balance across different glands. Sex hormones—oestrogen and progesterone in women and androgens including testosterone in men—are essential for reproduction, as are hormones secreted by the pituitary gland and hypothalamus in both men and women. EDCs either block the connection between these hormones and their receptors or increase or decrease their levels in blood. They also mimic the body’s natural hormonal activity and trick the body into blocking the natural hormones from doing their job. Any alteration in the amount or timing of the release of sex hormones in the body can alter a couple’s chances to conceive. That is because if these hormones do not get to the right place at the right time, sperm production or ovulation—both necessary for reproduction—can get hampered.

India, the second most populous country after China, finds itself at the centre of a paradoxical situation: an ever-mushrooming population on one hand and a dramatic year-on-year decline in its fertility rate on the other. A fertility rate of about 2.2—a couple having two children—is generally considered the replacement level, the rate at which the population would hold steady. When the fertility rate dips below this number, the population is expected to decline. As per the National Health Profile 2018, the total fertility rate fell below two children per woman in 12 states, and just about reached replacement levels in nine others. While there is no doubt that family planning has been the chief guiding force behind this, experts believe that the rising incidence of infertility is also to blame. “Infertility is on an alarming rise in India, with the country estimated to be contributing to nearly 25-30 per cent of all couples diagnosed with it the world over,” said Dr Neeta Singh, senior consultant and professor, division of reproductive medicine at the All India Institute of Medical Sciences. According to the Indian Society of Assisted Reproduction, one in six couples suffers from infertility, amounting to 27.5 million infertile couples trying for conception. “You can gauge the magnitude of the problem from the patient load at the AIIMS ART Centre,” said Singh. “As per the medical records for 2018-2019, nearly 15 lakh patients consulted the outpatient department, of which 5,468 patients underwent ART (assisted reproductive technology) treatment.”

ABC OF EDCs

And while the reasons vary—age can be a contributing factor, as can lifestyle issues like stress and obesity—scientists and researchers are more worried about what are called endocrine disrupting chemicals. EDCs represent a broad class of chemicals such as organochlorinated and organophosphate pesticides—used in agriculture and mosquito control—and industrial chemicals, plastics and plasticisers (used to soften plastics) and fuels. They are ubiquitous; EDCs can be found in food wraps and plastic water bottles, even in the perfume you wear, the tap water you drink and cook with, and the air you breathe. And, it is their unrestricted use that is harming our ability to have natural pregnancies.

“Their impact becomes even more magnified and frightening for India, as we are witnessing an ever-growing consumerist culture and have relatively easy regulations,” said Dr Kamlesh Sarkar, director, ICMR-National Institute of Occupational Health, Ahmedabad.

EDCs essentially interfere with and disrupt the body’s endocrine system that monitors the hormonal balance across different glands. Sex hormones—oestrogen and progesterone in women and androgens including testosterone in men—are essential for reproduction, as are hormones secreted by the pituitary gland and hypothalamus in both men and women. EDCs either block the connection between these hormones and their receptors or increase or decrease their levels in blood. They also mimic the body’s natural hormonal activity and trick the body into blocking the natural hormones from doing their job. Any alteration in the amount or timing of the release of sex hormones in the body can alter a couple’s chances to conceive. That is because if these hormones do not get to the right place at the right time, sperm production or ovulation—both necessary for reproduction—can get hampered.

Lasting damage: Villages were reporting higher incidence of infertility owing to the “high use” of fertilisers and pesticides | Aayush Goel

And, infertility is not just an urban issue. In a 2018 paper, Dr Sonia Malik, director of Delhi’s Southend IVF, wrote that villages were reporting higher incidence of infertility owing to the “high use” of fertilisers and pesticides. In some ways, it is not surprising that EDCs cause unfortunate consequences. For instance, since human reproductive processes are similar to those of other species, many pest-control chemicals designed to harm pest reproductive systems also damage human reproductive systems.

According to experts, health defects associated with EDCs include a range of reproductive problems, from declining sperm counts and reduced fertility to male and female reproductive tract abnormalities, reduction in the number of healthy eggs in ovarian reserves, loss of foetus, early puberty and menstrual problems. In 2014, professor Kaustubha Mohanty, department of chemical engineering, Indian Institute of Technology, Guwahati, carried out a research on the lingering effects of endosulfan, which was indiscriminately sprayed on cashew plantations in Kerala’s Kasaragod district and caused abnormalities and androgenic defects among children. Ten years after India banned it, it is still found to exist, said Mohanty. “Its residues were detected from air, water and soil. It is becoming increasingly difficult to get it out of the system because of its toxic properties,” he said.

Such toxicity goes beyond state borders. In 2006, Rajvi Mehta from Hope Infertility Clinic and Research Foundation, Bengaluru, evaluated 16,714 semen samples from five different cities of India and found that 38.3 per cent men from Kurnool and 37.4 per cent men in Jodhpur showed complete absence of motile sperms. Fifty-one per cent of men in Kurnool suffered from an abnormally low sperm count—the highest reported prevalence in the world, said Mehta. As per the study, a possible link could be established between infertility and high use of pesticides in Kurnool, where cotton is grown as a cash crop. The study, published in the recent issue of the Asian Journal of Andrology, was initiated after the Hope clinic got an unusually high number of referrals for male infertility treatment from Kurnool. “In Jodhpur, there is high level of fluoride in groundwater, and exposure to high fluoride levels has a detrimental effect on the male reproductive system in animals and can also cause disruption of reproductive hormones in men,” the paper said.

As per WHO, our exposure to EDCs has increased in the last two-and-a-half decades owing to their increased presence in our environment, be it food, water, air or everyday products. “Most of the EDCs are lipophilic (they can dissolve in fats and oils) and accumulate in the adipose tissue (body fat); thus they have a very long half-life in the body,” said Alka Dubey, programme coordinator, chemical and health, Toxics Link, an NGO that specialises in research on toxic chemicals in India. “Many of these substances either do not decay or decay slowly, while others may be metabolised to compounds that are more toxic than the parent chemicals.”

POP GOES THE BUBBLE

Persistent organic pollutants (POPs) are an example of such chemicals; the name says it all. POPs, such as polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) and organochlorinated pesticides (OCPs), are highly persistent, toxic, and accumulate in the body fat of humans and animals. Endocrine disruption is one of the recently considered consequences of POPs because of their hormone-altering capabilities. Studies have long established how DDT and PCBs (used in electrical equipment and coatings) can impact the growth and function of testicles, leading to abnormal sperm development and male infertility later in life. While the United States has banned DDT, it continues to be used in the fight against malaria and other diseases in India. However, following continuous use, insects have become resistant to it.

And, infertility is not just an urban issue. In a 2018 paper, Dr Sonia Malik, director of Delhi’s Southend IVF, wrote that villages were reporting higher incidence of infertility owing to the “high use” of fertilisers and pesticides. In some ways, it is not surprising that EDCs cause unfortunate consequences. For instance, since human reproductive processes are similar to those of other species, many pest-control chemicals designed to harm pest reproductive systems also damage human reproductive systems.

According to experts, health defects associated with EDCs include a range of reproductive problems, from declining sperm counts and reduced fertility to male and female reproductive tract abnormalities, reduction in the number of healthy eggs in ovarian reserves, loss of foetus, early puberty and menstrual problems. In 2014, professor Kaustubha Mohanty, department of chemical engineering, Indian Institute of Technology, Guwahati, carried out a research on the lingering effects of endosulfan, which was indiscriminately sprayed on cashew plantations in Kerala’s Kasaragod district and caused abnormalities and androgenic defects among children. Ten years after India banned it, it is still found to exist, said Mohanty. “Its residues were detected from air, water and soil. It is becoming increasingly difficult to get it out of the system because of its toxic properties,” he said.

Such toxicity goes beyond state borders. In 2006, Rajvi Mehta from Hope Infertility Clinic and Research Foundation, Bengaluru, evaluated 16,714 semen samples from five different cities of India and found that 38.3 per cent men from Kurnool and 37.4 per cent men in Jodhpur showed complete absence of motile sperms. Fifty-one per cent of men in Kurnool suffered from an abnormally low sperm count—the highest reported prevalence in the world, said Mehta. As per the study, a possible link could be established between infertility and high use of pesticides in Kurnool, where cotton is grown as a cash crop. The study, published in the recent issue of the Asian Journal of Andrology, was initiated after the Hope clinic got an unusually high number of referrals for male infertility treatment from Kurnool. “In Jodhpur, there is high level of fluoride in groundwater, and exposure to high fluoride levels has a detrimental effect on the male reproductive system in animals and can also cause disruption of reproductive hormones in men,” the paper said.

As per WHO, our exposure to EDCs has increased in the last two-and-a-half decades owing to their increased presence in our environment, be it food, water, air or everyday products. “Most of the EDCs are lipophilic (they can dissolve in fats and oils) and accumulate in the adipose tissue (body fat); thus they have a very long half-life in the body,” said Alka Dubey, programme coordinator, chemical and health, Toxics Link, an NGO that specialises in research on toxic chemicals in India. “Many of these substances either do not decay or decay slowly, while others may be metabolised to compounds that are more toxic than the parent chemicals.”

POP GOES THE BUBBLE

Persistent organic pollutants (POPs) are an example of such chemicals; the name says it all. POPs, such as polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) and organochlorinated pesticides (OCPs), are highly persistent, toxic, and accumulate in the body fat of humans and animals. Endocrine disruption is one of the recently considered consequences of POPs because of their hormone-altering capabilities. Studies have long established how DDT and PCBs (used in electrical equipment and coatings) can impact the growth and function of testicles, leading to abnormal sperm development and male infertility later in life. While the United States has banned DDT, it continues to be used in the fight against malaria and other diseases in India. However, following continuous use, insects have become resistant to it.

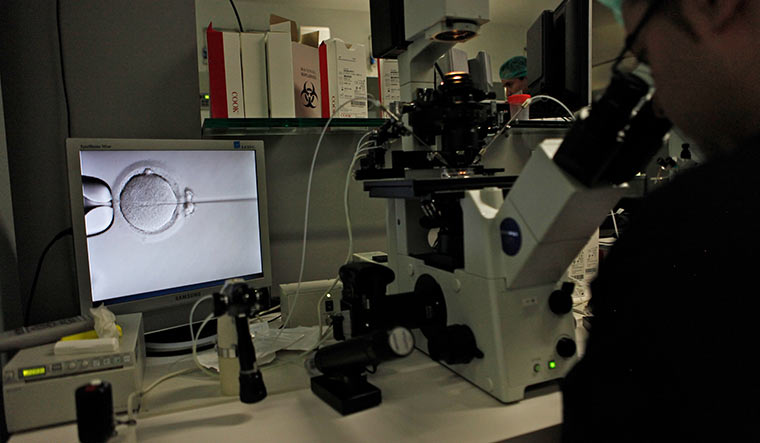

Trying hard: Sperm sample collection | Getty Images

It has left its footprints though; as early as 2001, Mumbai-based Bhabha Atomic Research Centre found residues of DDT and its metabolites in sediments and fish samples collected from the east and west coasts of India. Moreover, a 2018 report in the Archives of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology said that POPs were found in human breast milk samples collected from Bhatinda and Ludhiana in Punjab.

DROWNING IN PLASTIC

According to the Endocrine Society, the annual global production of plastics—which is found in almost everything we use and which contains EDCs—has grown from 50 million tonnes to 300 million tonnes since the 1970s.

Bisphenols and phthalates are two of the most common EDCs found in plastics; they mimic or interfere with reproduction regulated by oestrogens and androgens. Exposure to bisphenols and phthalates can lead to reduced fertility, pregnancy loss and infertility. Most people are exposed to bisphenol A through food and beverages into which BPA has leached from the container. BPA and its metabolites have been found in urine, blood, saliva, umbilical cord, placenta and amniotic fluid.

In a 2018 study, Ruckmani A. from the department of pharmacology, Chettinad Hospital and Research Institute in Chennai, assessed BPA levels in urine samples. The levels were “very high” in the urine of those who consumed food and drink from plastic containers. “Maximum level was seen in those who reused plastics as well as worked with BPA containing materials (9.01ng/ml) and the average level found in this study was higher than the level reported earlier (1.71ng/ml) in the Indian population,” said Ruckmani. “This may be due to the change in food habits, like eating fast food that are served in plastic containers and changes in quality of life.”

It has left its footprints though; as early as 2001, Mumbai-based Bhabha Atomic Research Centre found residues of DDT and its metabolites in sediments and fish samples collected from the east and west coasts of India. Moreover, a 2018 report in the Archives of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology said that POPs were found in human breast milk samples collected from Bhatinda and Ludhiana in Punjab.

DROWNING IN PLASTIC

According to the Endocrine Society, the annual global production of plastics—which is found in almost everything we use and which contains EDCs—has grown from 50 million tonnes to 300 million tonnes since the 1970s.

Bisphenols and phthalates are two of the most common EDCs found in plastics; they mimic or interfere with reproduction regulated by oestrogens and androgens. Exposure to bisphenols and phthalates can lead to reduced fertility, pregnancy loss and infertility. Most people are exposed to bisphenol A through food and beverages into which BPA has leached from the container. BPA and its metabolites have been found in urine, blood, saliva, umbilical cord, placenta and amniotic fluid.

In a 2018 study, Ruckmani A. from the department of pharmacology, Chettinad Hospital and Research Institute in Chennai, assessed BPA levels in urine samples. The levels were “very high” in the urine of those who consumed food and drink from plastic containers. “Maximum level was seen in those who reused plastics as well as worked with BPA containing materials (9.01ng/ml) and the average level found in this study was higher than the level reported earlier (1.71ng/ml) in the Indian population,” said Ruckmani. “This may be due to the change in food habits, like eating fast food that are served in plastic containers and changes in quality of life.”

Dr Neeta Singh

A clear evidence of BPA’s impact on fertility among Indian women was seen in a study carried out by Dr Firuza Parikh of FertilTree International Centre, Jaslok Hospital and Research Centre, Mumbai. Serum and follicular fluid samples were collected from 117 women in the median age of 34 who were seeking treatment for infertility and undergoing oocyte retrieval. The samples were collected during oocyte retrieval. “We found a clear correlation that was very disturbing. Given that in the past two decades, the number of couples coming to us for IVF has substantially increased, we can infer that EDCs have a definite role to play,” said Parikh.

Likewise, phthalates are a family of high-volume chemicals added to plastics to increase their flexibility, transparency, elasticity, durability and pliability. There are various forms of phthalates in use; however, DEHP and DnBP are the most commonly used in consumables, be it household items, cosmetics, personal care products, sanitary napkins or plastic toys for children. Toxicological and epidemiological studies have found that some phthalates, especially DnBP and DEHP, have oestrogenic and/or anti-androgenic properties that can lead to reproductive defects. Phthalates are estimated to have a half-life of about 12 hours in the air, 10 to 20 days in the soil and days to weeks in water. Also, as these have relatively high vapour pressure, it can easily get trapped in cloud masses. Thereafter, with rainfall, these phthalates reach and add to the pollutant levels of surface water.

In 2011, Ramakant Sahu of the Centre for Science and Environment and his team brought to the fore the chilling presence of phthalates in children’s toys in India. All toy samples showed the presence of one or more phthalates at a concentration ranging from 0.1 per cent to 16.2 per cent. Soft toys contain higher levels of phthalates compared to hard toys, as its primary function is to soften hard plastic. It was only in 2017 that the Bureau of Indian Standards restricted the use of certain phthalates in children’s toys and teethers. “Epidemiological studies have reported that exposure to phthalates leads to decline in male fertility, decreased anogenital distance and testicular dysgenesis (abnormal development) syndrome in male infants alongside other development- and behaviour-related issues,” stated a report by Toxics Link. Another report by the same NGO said that there was a high presence of phthalates in various samples of baby diapers, which, when dumped in garbage bins or landfills, can leach into the soil.

A 2014 study published by Mihir Tanay Das (Fakir Mohan University, Odisha), Pooja Ghosh (IIT Delhi) and Indu Shekhar Thakur (Jawaharlal Nehru University, Delhi) measured the estimated exposure of South Delhi population to 15 different phthalates. It revealed high intake of DnBP and DEHP in the adult urban population in the JNU campus and Okhla.

But it is the Thanjavur study that takes the cake. Consider this: something as simple as having hot idli sambar in takeaway polythene bags can pose a risk to your hormonal balance. In a 2016 study, samples of hot sambar and hot tea packed in plastic bags were collected from three major food and drink business centres around Thanjavur, including a tea shop and restaurant. Phthalate leachates were found in sambar, proving that they are highly soluble in oily food; none were found in the tea.

A clear evidence of BPA’s impact on fertility among Indian women was seen in a study carried out by Dr Firuza Parikh of FertilTree International Centre, Jaslok Hospital and Research Centre, Mumbai. Serum and follicular fluid samples were collected from 117 women in the median age of 34 who were seeking treatment for infertility and undergoing oocyte retrieval. The samples were collected during oocyte retrieval. “We found a clear correlation that was very disturbing. Given that in the past two decades, the number of couples coming to us for IVF has substantially increased, we can infer that EDCs have a definite role to play,” said Parikh.

Likewise, phthalates are a family of high-volume chemicals added to plastics to increase their flexibility, transparency, elasticity, durability and pliability. There are various forms of phthalates in use; however, DEHP and DnBP are the most commonly used in consumables, be it household items, cosmetics, personal care products, sanitary napkins or plastic toys for children. Toxicological and epidemiological studies have found that some phthalates, especially DnBP and DEHP, have oestrogenic and/or anti-androgenic properties that can lead to reproductive defects. Phthalates are estimated to have a half-life of about 12 hours in the air, 10 to 20 days in the soil and days to weeks in water. Also, as these have relatively high vapour pressure, it can easily get trapped in cloud masses. Thereafter, with rainfall, these phthalates reach and add to the pollutant levels of surface water.

In 2011, Ramakant Sahu of the Centre for Science and Environment and his team brought to the fore the chilling presence of phthalates in children’s toys in India. All toy samples showed the presence of one or more phthalates at a concentration ranging from 0.1 per cent to 16.2 per cent. Soft toys contain higher levels of phthalates compared to hard toys, as its primary function is to soften hard plastic. It was only in 2017 that the Bureau of Indian Standards restricted the use of certain phthalates in children’s toys and teethers. “Epidemiological studies have reported that exposure to phthalates leads to decline in male fertility, decreased anogenital distance and testicular dysgenesis (abnormal development) syndrome in male infants alongside other development- and behaviour-related issues,” stated a report by Toxics Link. Another report by the same NGO said that there was a high presence of phthalates in various samples of baby diapers, which, when dumped in garbage bins or landfills, can leach into the soil.

A 2014 study published by Mihir Tanay Das (Fakir Mohan University, Odisha), Pooja Ghosh (IIT Delhi) and Indu Shekhar Thakur (Jawaharlal Nehru University, Delhi) measured the estimated exposure of South Delhi population to 15 different phthalates. It revealed high intake of DnBP and DEHP in the adult urban population in the JNU campus and Okhla.

But it is the Thanjavur study that takes the cake. Consider this: something as simple as having hot idli sambar in takeaway polythene bags can pose a risk to your hormonal balance. In a 2016 study, samples of hot sambar and hot tea packed in plastic bags were collected from three major food and drink business centres around Thanjavur, including a tea shop and restaurant. Phthalate leachates were found in sambar, proving that they are highly soluble in oily food; none were found in the tea.

Srinivasan K.

“DEHP, a plasticiser, can migrate from packaging into fatty food, and leaching of plasticisers into food from packaging is the potential danger of this era,” wrote Srinivasan K. of department of food safety and quality testing, along with Singaravadivel K., at the Indian Institute of Food Processing Technology, Thanjavur. Fatty food such as milk, butter and meat are most susceptible to such leachates. “Literature review reveals that there is a correlation between phthalate metabolite concentrations in maternal breast milk and sex hormone concentration in male offspring,” said the researchers.

The same year, another study by ICMR-National Institute for Research in Reproductive Health analysed the estimated levels of BPA and phthalates in the plasma of fertile and infertile, non-smoking and non-drinking, urban Indian women, aged 20 to 40 years. BPA was detected in 77 per cent of plasma samples of infertile women and 29 per cent of fertile women. An increasing number of epidemiological studies show a widespread exposure of these chemicals to the general population, including pregnant women, men, children as well as foetuses in India. “The presence of these contaminants in amniotic fluid and cord blood indicates that these may pass transplacentally to the foetus,” read the paper. ”The developing foetus is dependent on sex steroids and thyroid hormones for maturation. These chemicals not only affect the developing embryo, but also have been shown to alter adult ovarian function. Hence, these agents have the potential to disrupt reproductive cyclicity and may also cause trans-generational effects by targeting oocyte maturation and maternal sex chromosomes.”

In the ICMR-NIRRH research, the infertile women who showed high levels of EDCs had been diagnosed with polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS) and endometriosis, two of the most widely reported causes of infertility among women in India. “Almost 30-35 per cent of my patients in the reproductive age group report PCOS, while 20 per cent suffer from the pain of living with endometriosis,” said Mumbai-based infertility specialist Dr Rishma Pai.

In his 2015 study, ‘Endometriosis: the clinical experience of 500 patients from India’, Dr Rahul Gajbhiye, head, Clinical Research Lab & Andrology Clinic at ICMR-NIRRH in Mumbai, stated that 2.6 crore women in India suffer from endometriosis. “In the cohort of women with endometriosis, 66 per cent women either had primary or secondary infertility and 33 per cent had history of miscarriage,” stated the study.

Is there a link between EDCs and endometriosis? In 2006, Dr B.S. Reddy, department of reproductive medicine, Bhagwan Mahavir Medical Research Centre in Hyderabad, evaluated the possible association between phthalate esters—EDCs used as plasticisers in nail polishes, hair sprays, solvents and perfumes—and the occurrence of endometriosis in Indian women. He collected blood samples from 49 infertile women with endometriosis and compared it with women free from the disease. The study clearly showed that “women with endometriosis showed significantly higher concentrations of phthalates, thereby suggesting that they may be causing endometriosis in Indian women”.

It is similar with PCOS, too. “In humans, cross-sectional data suggests that BPA concentrations are higher in women with PCOS than in reproductively healthy women,” said Dubey of Toxic Links. BPA, she added, also disrupts normal metabolic activity, making the body prone to obesity.

“In women undergoing IVF, those with the top 25 per cent body load of BPA levels were 211 per cent more likely to have implantation failure,” said Dr Pallavi Priyadarshini of Kokilaben Dhirubhai Ambani hospital, Mumbai.

KEEP CALM AND ‘CARRY’ ON

Long before EDCs gained attention, experts have been warning about the impact of a hectic lifestyle on libido and sex drive among young Indian couples. Chitramani Mukhopadhyay, a fashion designer from Kolkata, was frustrated at not being able to conceive after three years of marriage. All their tests were normal. It was the stress, they later figured. “But it is the chicken and egg situation. We are stressed, which is leading to infertility, which, in turn, is causing us more stress,” she said, almost laughing.

A study by the department of clinical psychology at Manipal University in 2016 found that 80 per cent of women had infertility-specific stress. The level of cortisol and alpha-amylase in saliva can be considered as a major biomarker of stress and anxiety. A 2018 research conducted by Barnali Ray Basu from the department of physiology, Surendranath College in Kolkata found that “increased salivary cortisol levels were seen in the PCOS population, suggesting a sustained stress scenario in their system. Men, too, suffer from a ‘dip in the mood’ resulting from hectic work routines”. A 2020 report by ADP India, a global payroll and compliance expertise company, based on a survey of 1,908 workers in India, stated that stress levels among the Indian workforce were significantly higher than the Asia-Pacific average of 60 per cent.

“I have clearly seen the change in the sperm count among our regular donors when they come to us after a vacation,” said Agatsya bank’s Choksi. “It is significantly higher and an indication of how everyday stress lowers the libido and sperm count in men. Curiously, most either do not believe it or simply brush it aside.” A case in point: Arnav Nawadh. Only after speaking to his andrologist did the 30-year-old realise that his sperm count and motility were dropping drastically because of regular hardcore gym workouts and sauna, along with holding up a stressful bank job.

“DEHP, a plasticiser, can migrate from packaging into fatty food, and leaching of plasticisers into food from packaging is the potential danger of this era,” wrote Srinivasan K. of department of food safety and quality testing, along with Singaravadivel K., at the Indian Institute of Food Processing Technology, Thanjavur. Fatty food such as milk, butter and meat are most susceptible to such leachates. “Literature review reveals that there is a correlation between phthalate metabolite concentrations in maternal breast milk and sex hormone concentration in male offspring,” said the researchers.

The same year, another study by ICMR-National Institute for Research in Reproductive Health analysed the estimated levels of BPA and phthalates in the plasma of fertile and infertile, non-smoking and non-drinking, urban Indian women, aged 20 to 40 years. BPA was detected in 77 per cent of plasma samples of infertile women and 29 per cent of fertile women. An increasing number of epidemiological studies show a widespread exposure of these chemicals to the general population, including pregnant women, men, children as well as foetuses in India. “The presence of these contaminants in amniotic fluid and cord blood indicates that these may pass transplacentally to the foetus,” read the paper. ”The developing foetus is dependent on sex steroids and thyroid hormones for maturation. These chemicals not only affect the developing embryo, but also have been shown to alter adult ovarian function. Hence, these agents have the potential to disrupt reproductive cyclicity and may also cause trans-generational effects by targeting oocyte maturation and maternal sex chromosomes.”

In the ICMR-NIRRH research, the infertile women who showed high levels of EDCs had been diagnosed with polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS) and endometriosis, two of the most widely reported causes of infertility among women in India. “Almost 30-35 per cent of my patients in the reproductive age group report PCOS, while 20 per cent suffer from the pain of living with endometriosis,” said Mumbai-based infertility specialist Dr Rishma Pai.

In his 2015 study, ‘Endometriosis: the clinical experience of 500 patients from India’, Dr Rahul Gajbhiye, head, Clinical Research Lab & Andrology Clinic at ICMR-NIRRH in Mumbai, stated that 2.6 crore women in India suffer from endometriosis. “In the cohort of women with endometriosis, 66 per cent women either had primary or secondary infertility and 33 per cent had history of miscarriage,” stated the study.

Is there a link between EDCs and endometriosis? In 2006, Dr B.S. Reddy, department of reproductive medicine, Bhagwan Mahavir Medical Research Centre in Hyderabad, evaluated the possible association between phthalate esters—EDCs used as plasticisers in nail polishes, hair sprays, solvents and perfumes—and the occurrence of endometriosis in Indian women. He collected blood samples from 49 infertile women with endometriosis and compared it with women free from the disease. The study clearly showed that “women with endometriosis showed significantly higher concentrations of phthalates, thereby suggesting that they may be causing endometriosis in Indian women”.

It is similar with PCOS, too. “In humans, cross-sectional data suggests that BPA concentrations are higher in women with PCOS than in reproductively healthy women,” said Dubey of Toxic Links. BPA, she added, also disrupts normal metabolic activity, making the body prone to obesity.

“In women undergoing IVF, those with the top 25 per cent body load of BPA levels were 211 per cent more likely to have implantation failure,” said Dr Pallavi Priyadarshini of Kokilaben Dhirubhai Ambani hospital, Mumbai.

KEEP CALM AND ‘CARRY’ ON

Long before EDCs gained attention, experts have been warning about the impact of a hectic lifestyle on libido and sex drive among young Indian couples. Chitramani Mukhopadhyay, a fashion designer from Kolkata, was frustrated at not being able to conceive after three years of marriage. All their tests were normal. It was the stress, they later figured. “But it is the chicken and egg situation. We are stressed, which is leading to infertility, which, in turn, is causing us more stress,” she said, almost laughing.

A study by the department of clinical psychology at Manipal University in 2016 found that 80 per cent of women had infertility-specific stress. The level of cortisol and alpha-amylase in saliva can be considered as a major biomarker of stress and anxiety. A 2018 research conducted by Barnali Ray Basu from the department of physiology, Surendranath College in Kolkata found that “increased salivary cortisol levels were seen in the PCOS population, suggesting a sustained stress scenario in their system. Men, too, suffer from a ‘dip in the mood’ resulting from hectic work routines”. A 2020 report by ADP India, a global payroll and compliance expertise company, based on a survey of 1,908 workers in India, stated that stress levels among the Indian workforce were significantly higher than the Asia-Pacific average of 60 per cent.

“I have clearly seen the change in the sperm count among our regular donors when they come to us after a vacation,” said Agatsya bank’s Choksi. “It is significantly higher and an indication of how everyday stress lowers the libido and sperm count in men. Curiously, most either do not believe it or simply brush it aside.” A case in point: Arnav Nawadh. Only after speaking to his andrologist did the 30-year-old realise that his sperm count and motility were dropping drastically because of regular hardcore gym workouts and sauna, along with holding up a stressful bank job.

Dr Aditi Dani

In the case of Simaira Vipuldas and her husband, stress was a major factor contributing to their inability to conceive naturally. So, Simaira quit her job as a customer relationship manager with a leading publishing company. “Throughout the years I worked, I gained close to 20kg due to the erratic lifestyle,” she said. “Work pressure and the accompanying exhaustion resulting from daily travel further added to the stress. I knew I had to prioritise having a child, else it won’t work out ever.” It took the couple six years to conceive after Simaira was diagnosed with PCOS.

As per a study by the PCOS Society in India, one in every 10 women has PCOS and resulting infertility. “PCOS is undeniably a lifestyle-related problem and it is the number one reason for infertility among women,” said Dr Shashank Joshi, vice president, PCOS Society of India.

In the past two-and-a-half decades, there has been a complete shift in the infertility picture in India, said Dani of Masina Hospital. “Back when I started my practice, India reported infertility cases that were direct, in the sense that they had a clear medical or biological cause,” she said. “But now, we are observing a very lifestyle-related infertility that stems from increasing age, late marriages due to career goals, putting family planning on the back burner and from the kind of chemicals and pollutants we are exposed to.” Women as young as 25 have very few good quality eggs left, she added. “The thing is that now in men and women, the ratio of hormones is itself being attacked. The ratios are being changed by the way the chemicals interact with the hormones in-utero,” said Dani.

This has led to the coinage of ‘unexplained infertility’, an oft-used term these days. This happens when all other biological and medical parameters are normal, yet a couple cannot conceive even after a full year of trying. “In over 25 per cent of infertility cases, no detectable cause can be traced after routine tests, which leaves the case as unexplained infertility,” said Dr Naina Kumar, department of obstetrics and gynaecology, Mahatma Gandhi Institute of Medical Sciences, Wardha, Maharashtra, in her research on trends in male factor infertility.

After four miscarriages, Abha Devdutta was thrilled when her next pregnancy progressed easily to 12 weeks. She was 35 then. But when she went to get herself checked for any chromosomal abnormalities in the foetus, it was found that she had once again lost the baby. Devastated, the couple has since given up on parenthood. “It is bewildering, because each of our tests has come out normal and we have no medical or biological problems at all,” she said. She has now switched to a simple and healthy lifestyle—no more junk food, late night bingeing on food and flicks, no hoarding of plastics at home. “At present, we are taking each day as it comes,” she said. “Until we think of trying once again, we are enjoying the love of our nephews and nieces.”

In India, about 10-20 per cent of known pregnancies end in miscarriage. “Yes, we are observing more miscarriages now than a decade or so ago,” said Parikh. “But it is not just related to women. Even if female fertility, as is common knowledge, has a best before date of 35, while the fertility shelf life for men extends to 45-50 years, we are now learning that as the semen quality is going down, the risk of miscarriages is going up because of bad sperm.”

A lot of that has to do with smoking, said Dr Kshitiz Murdia, cofounder and CEO of Indira IVF. “Several studies have shown that in comparison to non-smokers, active smokers have 14 per cent more chances of suffering from infertility and 30 per cent more chances of early menopause,” he said.

Puffs aside, another addiction that may impact our reproductive health is our device dependence. Radiations from cell phones, laptops, Wi-Fi or microwave ovens may affect sperm development and quality. “Studies reveal that exposure to cell phones, microwave ovens, laptops or Wi-Fi produces deleterious effects on the testes, which may affect sperm count, morphology, motility, an increased DNA damage…,” wrote Dr Ashok Agarwal, director of research at the American Centre for Reproductive Medicine at Cleveland Clinic, in his research on effects of non-ionising radiations that come from cell phones, laptops and microwaves.

The next time someone chides you for propping the laptop on your lap, just heed their advice. For, Agarwal and his team have found that the exposure of sperms to a wireless internet-connected laptop decreased motility. “To our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate the direct impact of laptop use on human spermatozoa,” he said. “Keeping a laptop connected wirelessly to the internet on the lap near the testes may result in decreased male fertility.” He rued the fact that there is limited research on protective measures.

THE WAR WITHIN

T. Velpandiyan, professor at AIIMS, is currently concluding a study where he and his team are trying to figure out which type of EDCs are present in excess in water resources in NCR and its impact on citizens, as when water gets contaminated, it can easily get into the food cycle. He revealed that soya milk contributes to infertility, too, as it contains a compound called genistein, which is a mimic of actual oestrogen hormone, and hence is also called as phytoestrogen. “If any male takes it then he will slowly have a lesser sperm count and reduced libido,” he said.

Until a point, the chemicals, including bisphenols, get metabolised in the body as the body has a detoxifying mechanism. Beyond that, when the concentration of these chemicals exceeds the prescribed limits, problems come up. But these limits are set by European and WHO standards; India has no such prescribed limits.

Velpandiyan and his team are trying to rectify that. But the problem is that many of these EDCs in India are non-degradable. With our tropical climate, any toxin is expected to degrade, said Pandiyan. “But shockingly, many get accumulated in groundwater and borewells and thereby enter the food chain,” he said. “While in China, they know the levels of each and every chemical and the contamination it causes, in India, we have not done such research. We do know that there is a large presence of EDCs but not exactly in what measurements do they contribute to human health damage. One reason for this is whenever we apply for such research, the funding agency seems uninterested.”

In the case of Simaira Vipuldas and her husband, stress was a major factor contributing to their inability to conceive naturally. So, Simaira quit her job as a customer relationship manager with a leading publishing company. “Throughout the years I worked, I gained close to 20kg due to the erratic lifestyle,” she said. “Work pressure and the accompanying exhaustion resulting from daily travel further added to the stress. I knew I had to prioritise having a child, else it won’t work out ever.” It took the couple six years to conceive after Simaira was diagnosed with PCOS.

As per a study by the PCOS Society in India, one in every 10 women has PCOS and resulting infertility. “PCOS is undeniably a lifestyle-related problem and it is the number one reason for infertility among women,” said Dr Shashank Joshi, vice president, PCOS Society of India.

In the past two-and-a-half decades, there has been a complete shift in the infertility picture in India, said Dani of Masina Hospital. “Back when I started my practice, India reported infertility cases that were direct, in the sense that they had a clear medical or biological cause,” she said. “But now, we are observing a very lifestyle-related infertility that stems from increasing age, late marriages due to career goals, putting family planning on the back burner and from the kind of chemicals and pollutants we are exposed to.” Women as young as 25 have very few good quality eggs left, she added. “The thing is that now in men and women, the ratio of hormones is itself being attacked. The ratios are being changed by the way the chemicals interact with the hormones in-utero,” said Dani.

This has led to the coinage of ‘unexplained infertility’, an oft-used term these days. This happens when all other biological and medical parameters are normal, yet a couple cannot conceive even after a full year of trying. “In over 25 per cent of infertility cases, no detectable cause can be traced after routine tests, which leaves the case as unexplained infertility,” said Dr Naina Kumar, department of obstetrics and gynaecology, Mahatma Gandhi Institute of Medical Sciences, Wardha, Maharashtra, in her research on trends in male factor infertility.

After four miscarriages, Abha Devdutta was thrilled when her next pregnancy progressed easily to 12 weeks. She was 35 then. But when she went to get herself checked for any chromosomal abnormalities in the foetus, it was found that she had once again lost the baby. Devastated, the couple has since given up on parenthood. “It is bewildering, because each of our tests has come out normal and we have no medical or biological problems at all,” she said. She has now switched to a simple and healthy lifestyle—no more junk food, late night bingeing on food and flicks, no hoarding of plastics at home. “At present, we are taking each day as it comes,” she said. “Until we think of trying once again, we are enjoying the love of our nephews and nieces.”

In India, about 10-20 per cent of known pregnancies end in miscarriage. “Yes, we are observing more miscarriages now than a decade or so ago,” said Parikh. “But it is not just related to women. Even if female fertility, as is common knowledge, has a best before date of 35, while the fertility shelf life for men extends to 45-50 years, we are now learning that as the semen quality is going down, the risk of miscarriages is going up because of bad sperm.”

A lot of that has to do with smoking, said Dr Kshitiz Murdia, cofounder and CEO of Indira IVF. “Several studies have shown that in comparison to non-smokers, active smokers have 14 per cent more chances of suffering from infertility and 30 per cent more chances of early menopause,” he said.

Puffs aside, another addiction that may impact our reproductive health is our device dependence. Radiations from cell phones, laptops, Wi-Fi or microwave ovens may affect sperm development and quality. “Studies reveal that exposure to cell phones, microwave ovens, laptops or Wi-Fi produces deleterious effects on the testes, which may affect sperm count, morphology, motility, an increased DNA damage…,” wrote Dr Ashok Agarwal, director of research at the American Centre for Reproductive Medicine at Cleveland Clinic, in his research on effects of non-ionising radiations that come from cell phones, laptops and microwaves.

The next time someone chides you for propping the laptop on your lap, just heed their advice. For, Agarwal and his team have found that the exposure of sperms to a wireless internet-connected laptop decreased motility. “To our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate the direct impact of laptop use on human spermatozoa,” he said. “Keeping a laptop connected wirelessly to the internet on the lap near the testes may result in decreased male fertility.” He rued the fact that there is limited research on protective measures.

THE WAR WITHIN

T. Velpandiyan, professor at AIIMS, is currently concluding a study where he and his team are trying to figure out which type of EDCs are present in excess in water resources in NCR and its impact on citizens, as when water gets contaminated, it can easily get into the food cycle. He revealed that soya milk contributes to infertility, too, as it contains a compound called genistein, which is a mimic of actual oestrogen hormone, and hence is also called as phytoestrogen. “If any male takes it then he will slowly have a lesser sperm count and reduced libido,” he said.

Until a point, the chemicals, including bisphenols, get metabolised in the body as the body has a detoxifying mechanism. Beyond that, when the concentration of these chemicals exceeds the prescribed limits, problems come up. But these limits are set by European and WHO standards; India has no such prescribed limits.

Velpandiyan and his team are trying to rectify that. But the problem is that many of these EDCs in India are non-degradable. With our tropical climate, any toxin is expected to degrade, said Pandiyan. “But shockingly, many get accumulated in groundwater and borewells and thereby enter the food chain,” he said. “While in China, they know the levels of each and every chemical and the contamination it causes, in India, we have not done such research. We do know that there is a large presence of EDCs but not exactly in what measurements do they contribute to human health damage. One reason for this is whenever we apply for such research, the funding agency seems uninterested.”

Alka Dubey

Also, India has been dragging its feet on regulating the EDCs. It did so with regulations regarding pesticides in carbonated water. That was despite the Centre for Science and Environment twice finding high levels of pesticides and insecticides—high enough to cause birth defects, damage to reproductive systems and severe disruption of the immune system—in soft drinks sold in India, including market leaders Pepsi and Coca Cola. It was only three years after the second study in 2006 that the health ministry notified standards for pesticide levels in carbonated water. “In the past, we had found pesticides in bottled water and soft drinks, which meant that companies were not taking adequate measures to avoid their presence,” said Amit Khurana of CSE. “It also told us that pesticides are present in groundwater. We had also found pesticides in the blood of farmers, which means that pesticides can accumulate in our bodies.” He added that while it was clear that pesticide misuse is common in Indian agriculture, “even those pesticides that are considered hazardous are not regulated the way they should be”.

The same is the case with phthalates. “As awareness regarding these among people grows, some cosmetic and children toy brands, for instance, are proactively mentioning their products as paraben- and phthalate-free,” said Das of Fakir Mohan University. “But there is no regulation mandating that products be phthalate-free or within certain limits.”

But India is taking baby steps. Take, for instance, the perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAs), yet another group of EDCs that are used widely in industrial applications in India, from fire-fighting foams to non-stick pans and textile coatings. A 2008 study found significant PFAS levels in breast milk of women from Chidambaram, Kolkata and Chennai. Last September, BIS announced that it was developing a framework for regulating PFAS by adopting international standards.

“We are controlling the use of EDCs by prescribing the limits specified in the relevant Indian standards that are referred to in various regulations,” said Nagamani T., head, petroleum, coal and related products department, BIS. “Toys (Quality Control) Order, 2020, is one of the best examples in this regard.”

But do these regulations make real impact? Take, for instance, the Plastic Waste Management Rules, 2016, which was passed the same year as the sambar study publication, increasing the minimum thickness of plastic bags from 40 to 50 microns. However, as Srinivasan said, “Only thing is that the possibility of leaching of phthalates will be less if the plastic bags are above 50 microns. But most of the plastic covers in which we get food, as per my observations, are well below this limit.”

Infertility issues have always been there, but they were never this grave or alarming. While the food we eat, the water we drink, the air we breathe, the stress we take and our sleep patterns all contribute to infertility, the most crucial factor is the one that has penetrated every aspect of our lives—endocrine disrupting chemicals. Time for a pregnant pause?

Some names have been changed.

Also, India has been dragging its feet on regulating the EDCs. It did so with regulations regarding pesticides in carbonated water. That was despite the Centre for Science and Environment twice finding high levels of pesticides and insecticides—high enough to cause birth defects, damage to reproductive systems and severe disruption of the immune system—in soft drinks sold in India, including market leaders Pepsi and Coca Cola. It was only three years after the second study in 2006 that the health ministry notified standards for pesticide levels in carbonated water. “In the past, we had found pesticides in bottled water and soft drinks, which meant that companies were not taking adequate measures to avoid their presence,” said Amit Khurana of CSE. “It also told us that pesticides are present in groundwater. We had also found pesticides in the blood of farmers, which means that pesticides can accumulate in our bodies.” He added that while it was clear that pesticide misuse is common in Indian agriculture, “even those pesticides that are considered hazardous are not regulated the way they should be”.

The same is the case with phthalates. “As awareness regarding these among people grows, some cosmetic and children toy brands, for instance, are proactively mentioning their products as paraben- and phthalate-free,” said Das of Fakir Mohan University. “But there is no regulation mandating that products be phthalate-free or within certain limits.”

But India is taking baby steps. Take, for instance, the perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAs), yet another group of EDCs that are used widely in industrial applications in India, from fire-fighting foams to non-stick pans and textile coatings. A 2008 study found significant PFAS levels in breast milk of women from Chidambaram, Kolkata and Chennai. Last September, BIS announced that it was developing a framework for regulating PFAS by adopting international standards.

“We are controlling the use of EDCs by prescribing the limits specified in the relevant Indian standards that are referred to in various regulations,” said Nagamani T., head, petroleum, coal and related products department, BIS. “Toys (Quality Control) Order, 2020, is one of the best examples in this regard.”

But do these regulations make real impact? Take, for instance, the Plastic Waste Management Rules, 2016, which was passed the same year as the sambar study publication, increasing the minimum thickness of plastic bags from 40 to 50 microns. However, as Srinivasan said, “Only thing is that the possibility of leaching of phthalates will be less if the plastic bags are above 50 microns. But most of the plastic covers in which we get food, as per my observations, are well below this limit.”

Infertility issues have always been there, but they were never this grave or alarming. While the food we eat, the water we drink, the air we breathe, the stress we take and our sleep patterns all contribute to infertility, the most crucial factor is the one that has penetrated every aspect of our lives—endocrine disrupting chemicals. Time for a pregnant pause?

Some names have been changed.

SEE

by M Bookchin · Cited by 247 — Our Synthetic Environment. Murray Bookchin. 1962. Table of contents. Chapter 1: THE PROBLEM. Chapter 2: AGRICULTURE AND HEALTH. Chapter 3: ...

There is a whole sexual substratum of the historical dialectic that Engels at times dimly perceives, but because he can see sexuality only through an economic filter ...

No comments:

Post a Comment