By Georgina Torbet

October 2, 2021

The European and Japanese mission BepiColombo has made its first flyby of Mercury, capturing images of the planet it will eventually be exploring in more depth. In order to get close to the planet, the spacecraft makes use of the planet’s gravity to make increasingly close approaches. It has already made one flyby of Earth and two of Venus, and this was the first of six flybys of Mercury.

As the craft passed by, it snapped images of Mercury using the Monitoring Camera 3 on its Mercury Transfer Module, which captures images in black and white with a resolution of 1024 x 1024 pixels. In the image below, you can see the spacecraft’s antennae and magnetometer boom.

The joint European-Japanese BepiColombo mission captured this view of Mercury on 1 October 2021 as the spacecraft flew past the planet for a gravity assist maneuver.ESA/BepiColombo/MTM, CC BY-SA 3.0 IGO

The closest image was taken from around 620 miles from the planet, which is close enough to see impact craters on its surface.

“It was an incredible feeling seeing these almost-live pictures of Mercury,” said Valentina Galluzzi, co-investigator of BepiColombo’s SIMBIO-SYS imaging system that will be used once in Mercury orbit. “It really made me happy meeting the planet I have been studying since the very first years of my research career, and I am eager to work on new Mercury images in the future.”

The closest image was taken from around 620 miles from the planet, which is close enough to see impact craters on its surface.

“It was an incredible feeling seeing these almost-live pictures of Mercury,” said Valentina Galluzzi, co-investigator of BepiColombo’s SIMBIO-SYS imaging system that will be used once in Mercury orbit. “It really made me happy meeting the planet I have been studying since the very first years of my research career, and I am eager to work on new Mercury images in the future.”

The joint European-Japanese BepiColombo mission captured this view of Mercury on 1 October 2021 as the spacecraft flew past the planet for a gravity assist maneuver. The image was taken at 23:40:27 UTC by the Mercury Transfer Module’s Monitoring Camera 3 when the spacecraft was 1183 km from Mercury.ESA/BepiColombo/MTM, CC BY-SA 3.0 IGO

The flyby was also a chance to check that the cameras and other instruments were working as expected and that everything is healthy with the spacecraft.

“In addition to the images we obtained from the monitoring cameras we also operated several science instruments on the Mercury Planetary Orbiter and Mercury Magnetospheric Orbiter,” said Johannes Benkhoff, ESA’s BepiColombo project scientist. “I’m really looking forward to seeing these results. It was a fantastic night shift with fabulous teamwork, and with many happy faces.”

BepiColombo will now continue making flybys of Mercury, with its next set to occur in June] 2022 and its main science mission beginning in 2026.

“The flyby was flawless from the spacecraft point of view, and it’s incredible to finally see our target planet,” said Elsa Montagnon, Spacecraft Operations Manager for the mission.

The flyby was also a chance to check that the cameras and other instruments were working as expected and that everything is healthy with the spacecraft.

“In addition to the images we obtained from the monitoring cameras we also operated several science instruments on the Mercury Planetary Orbiter and Mercury Magnetospheric Orbiter,” said Johannes Benkhoff, ESA’s BepiColombo project scientist. “I’m really looking forward to seeing these results. It was a fantastic night shift with fabulous teamwork, and with many happy faces.”

BepiColombo will now continue making flybys of Mercury, with its next set to occur in June] 2022 and its main science mission beginning in 2026.

“The flyby was flawless from the spacecraft point of view, and it’s incredible to finally see our target planet,” said Elsa Montagnon, Spacecraft Operations Manager for the mission.

Mercury Mission Flies by Closest Planet to the Sun for the First Time

SCIENCE & TECHWire Service Oct 2, 2021

SCIENCE & TECHWire Service Oct 2, 2021

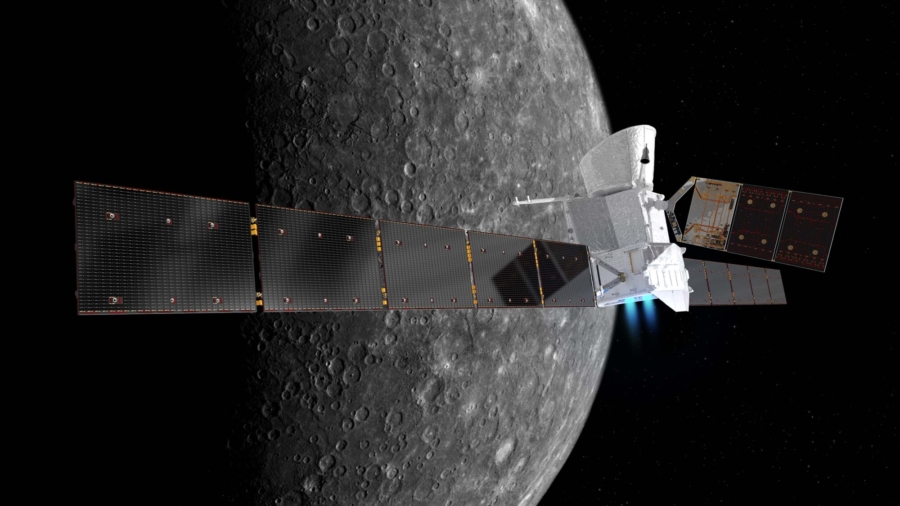

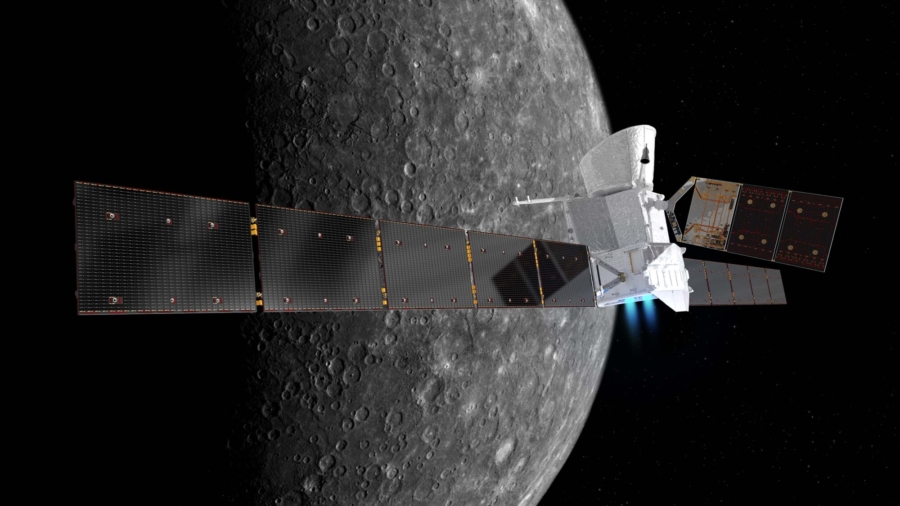

An artist’s illustration of BepiColombo over Mercury.

(ESA/ATG medialab/NASA/JPL)

The smallest planet in our solar system was getting photographed Friday by a European-Japanese space probe making its closest trip past the sphere on its seven-year mission.

The BepiColombo mission made its first flyby of Mercury around 7:34 p.m. ET on Friday, passing within 124 miles (200 kilometers) of the planet’s surface.

“BepiColombo is now as close to Mercury as it will get in this first of six Mercury flybys,” the European Space Agency (ESA) said on Twitter.

During the flyby, BepiColombo is collecting science data and images, and sending them back to Earth.

The mission, jointly managed by the ESA and the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency, launched in October 2018. It will ultimately make six total flybys of Mercury before entering orbit around the planet in December 2025.

The mission will actually place two probes in orbit around Mercury: the ESA-led Mercury Planetary Orbiter and the JAXA-led Mercury Magnetospheric Orbiter, Mio. The orbiters will remain stacked in their current configuration with the Mercury Transfer Module until deployment in 2025.

Once the Bepicolombo spacecraft approaches Mercury to begin orbit, the Mercury Transfer Module part of the spacecraft will separate and the two orbiters will begin circling the planet.

Both probes will spend a year collecting data to help scientists better understand the small, mysterious planet, such as determining more about the processes that unfold on its surface and its magnetic field. This information could reveal the origin and evolution of the closest planet to the sun.

During Friday’s flyby, the spacecraft’s main camera was being shielded and unable to capture high-resolution images. But two of the spacecraft’s three monitoring cameras will take photos of the planet’s northern and southern hemispheres just after the close approach from about 621 miles (1,000 kilometers).

BepiColombo will fly by the planet’s night side, so images during the closest approach wouldn’t be able to show much detail.

The mission team anticipates the images will show large impact craters that are scattered across Mercury’s surface, much like our moon. The researchers can use the images to map Mercury’s surface and learn more about the planet’s composition.

Some of the instruments on both orbiters will be turned on during the flyby so they can get a first whiff of Mercury’s magnetic field, plasma and particles.

The flyby has a timely occurrence on the 101st anniversary of Giuseppe “Bepi” Colombo’s birthday, the Italian scientist and engineer who is the namesake of the mission. Colombo’s work helped explain Mercury’s rotation as it orbits the sun and enabled NASA’s Mariner 10 spacecraft to perform three Mercury flybys rather than just one by using a gravity assist from Venus. He determined that the point where spacecraft fly by planets could actually help make future passes possible.

Mariner 10 was the first spacecraft sent to study Mercury, and it successfully completed its three flybys in 1974 and 1975. Next, NASA sent its Messenger spacecraft to perform three flybys of Mercury in 2008 and 2009, and it orbited the planet from 2011 to 2015.

Now, BepiColombo will take up the task of providing scientists with the best information to unlock the planet’s mysteries as the second mission to orbit Mercury and the most complex one to date.

“We’re really looking forward to seeing the first results from measurements taken so close to Mercury’s surface,” said Johannes Benkhoff, ESA’s BepiColombo project scientist, in a statement. “When I started working as project scientist on BepiColombo in January 2008, NASA’s Messenger mission had its first flyby at Mercury. Now it’s our turn. It’s a fantastic feeling!”

Why Mercury?

Little is known about the history, surface or atmosphere of Mercury, which is notoriously difficult to study because of its proximity to the sun. It’s the least explored of the four rocky planets of the inner solar system, including Venus, Earth and Mars. The sun’s brightness behind Mercury makes the little planet hard to observe from Earth, too.

BepiColombo will have to fire xenon gas constantly from two of four specially designed engines in order to permanently brake against the sun’s enormous gravitational pull. Its distance from Earth also makes it difficult to reach—more energy is required to allow BepiColombo to “fall” toward the planet than is needed when sending missions to Pluto.

A heat shield and titanium insulation have also been applied to the spacecraft to protect it from intense heat of up to 662 degrees Fahrenheit (350 degrees Celsius).

The instruments on the two orbiters will investigate ice within the planet’s polar craters, why it has a magnetic field, and the nature of the “hollows” on the planet’s surface.

Mercury is full of mysteries for such a small planet, just slightly larger than our moon. What scientists do know is that during the day, temperatures can reach highs of 800 degrees Fahrenheit (430 degrees Celsius), but the planet’s thin atmosphere means that it can dip to negative 290 degrees Fahrenheit (negative 180 degrees Celsius) at night.

Even though Mercury is the closest planet to the sun at about 36 million miles (58 million kilometers) from our star on average, the hottest planet in our solar system is actually Venus because it has a dense atmosphere. But Mercury is definitely the fastest of the planets, completing one orbit around the sun every 88 days—which is why it was named for the quick, wing-footed messenger of the Roman gods.

If we could stand on the surface of Mercury, the sun would appear three times larger than it does on Earth and the sunlight would be blinding because it’s seven times brighter.

Mercury’s unusual rotation and oval-shaped orbit around the sun means our star seems to quickly rise, set and rise again on some parts of the planet, and a similar phenomenon occurs at sunset.

The CNN Wire contributed to this report

The smallest planet in our solar system was getting photographed Friday by a European-Japanese space probe making its closest trip past the sphere on its seven-year mission.

The BepiColombo mission made its first flyby of Mercury around 7:34 p.m. ET on Friday, passing within 124 miles (200 kilometers) of the planet’s surface.

“BepiColombo is now as close to Mercury as it will get in this first of six Mercury flybys,” the European Space Agency (ESA) said on Twitter.

During the flyby, BepiColombo is collecting science data and images, and sending them back to Earth.

The mission, jointly managed by the ESA and the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency, launched in October 2018. It will ultimately make six total flybys of Mercury before entering orbit around the planet in December 2025.

The mission will actually place two probes in orbit around Mercury: the ESA-led Mercury Planetary Orbiter and the JAXA-led Mercury Magnetospheric Orbiter, Mio. The orbiters will remain stacked in their current configuration with the Mercury Transfer Module until deployment in 2025.

Once the Bepicolombo spacecraft approaches Mercury to begin orbit, the Mercury Transfer Module part of the spacecraft will separate and the two orbiters will begin circling the planet.

Both probes will spend a year collecting data to help scientists better understand the small, mysterious planet, such as determining more about the processes that unfold on its surface and its magnetic field. This information could reveal the origin and evolution of the closest planet to the sun.

During Friday’s flyby, the spacecraft’s main camera was being shielded and unable to capture high-resolution images. But two of the spacecraft’s three monitoring cameras will take photos of the planet’s northern and southern hemispheres just after the close approach from about 621 miles (1,000 kilometers).

BepiColombo will fly by the planet’s night side, so images during the closest approach wouldn’t be able to show much detail.

The mission team anticipates the images will show large impact craters that are scattered across Mercury’s surface, much like our moon. The researchers can use the images to map Mercury’s surface and learn more about the planet’s composition.

Some of the instruments on both orbiters will be turned on during the flyby so they can get a first whiff of Mercury’s magnetic field, plasma and particles.

The flyby has a timely occurrence on the 101st anniversary of Giuseppe “Bepi” Colombo’s birthday, the Italian scientist and engineer who is the namesake of the mission. Colombo’s work helped explain Mercury’s rotation as it orbits the sun and enabled NASA’s Mariner 10 spacecraft to perform three Mercury flybys rather than just one by using a gravity assist from Venus. He determined that the point where spacecraft fly by planets could actually help make future passes possible.

Mariner 10 was the first spacecraft sent to study Mercury, and it successfully completed its three flybys in 1974 and 1975. Next, NASA sent its Messenger spacecraft to perform three flybys of Mercury in 2008 and 2009, and it orbited the planet from 2011 to 2015.

Now, BepiColombo will take up the task of providing scientists with the best information to unlock the planet’s mysteries as the second mission to orbit Mercury and the most complex one to date.

“We’re really looking forward to seeing the first results from measurements taken so close to Mercury’s surface,” said Johannes Benkhoff, ESA’s BepiColombo project scientist, in a statement. “When I started working as project scientist on BepiColombo in January 2008, NASA’s Messenger mission had its first flyby at Mercury. Now it’s our turn. It’s a fantastic feeling!”

Why Mercury?

Little is known about the history, surface or atmosphere of Mercury, which is notoriously difficult to study because of its proximity to the sun. It’s the least explored of the four rocky planets of the inner solar system, including Venus, Earth and Mars. The sun’s brightness behind Mercury makes the little planet hard to observe from Earth, too.

BepiColombo will have to fire xenon gas constantly from two of four specially designed engines in order to permanently brake against the sun’s enormous gravitational pull. Its distance from Earth also makes it difficult to reach—more energy is required to allow BepiColombo to “fall” toward the planet than is needed when sending missions to Pluto.

A heat shield and titanium insulation have also been applied to the spacecraft to protect it from intense heat of up to 662 degrees Fahrenheit (350 degrees Celsius).

The instruments on the two orbiters will investigate ice within the planet’s polar craters, why it has a magnetic field, and the nature of the “hollows” on the planet’s surface.

Mercury is full of mysteries for such a small planet, just slightly larger than our moon. What scientists do know is that during the day, temperatures can reach highs of 800 degrees Fahrenheit (430 degrees Celsius), but the planet’s thin atmosphere means that it can dip to negative 290 degrees Fahrenheit (negative 180 degrees Celsius) at night.

Even though Mercury is the closest planet to the sun at about 36 million miles (58 million kilometers) from our star on average, the hottest planet in our solar system is actually Venus because it has a dense atmosphere. But Mercury is definitely the fastest of the planets, completing one orbit around the sun every 88 days—which is why it was named for the quick, wing-footed messenger of the Roman gods.

If we could stand on the surface of Mercury, the sun would appear three times larger than it does on Earth and the sunlight would be blinding because it’s seven times brighter.

Mercury’s unusual rotation and oval-shaped orbit around the sun means our star seems to quickly rise, set and rise again on some parts of the planet, and a similar phenomenon occurs at sunset.

The CNN Wire contributed to this report

No comments:

Post a Comment