Scan of mummy reveals damage, repair, amulets and treasure

The scan revealed that amulets of scarabs, snails, serpent heads and the Eye of Horus in gold, clay and stone were arranged around the body

Author of the article:Joseph Brean

Publishing date:Dec 28, 2021 •

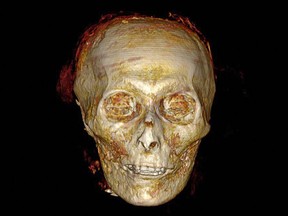

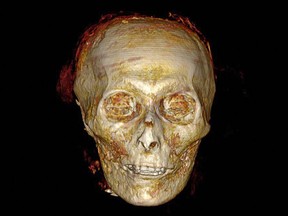

The CT scan also produced an image of his face, revealing a slightly bucktoothed 35-year-old man with a narrow chin, sunken cheeks, small eyes and a pierced left ear. His brain remains in place, shrivelled onto the back of his skull. He was circumcised. Amulets of scarabs, snails, serpent heads and the Eye of Horus in gold, clay and stone are arranged around the body. There is an incision on his left flank through which he was eviscerated. Alive, he was short, probably about five foot six and a bit, and he is now the earliest known mummy of the New Kingdom golden age of Egyptian pharaohs whose arms are crossed at the chest.

No cause of death was obvious, but postmortem damage was revealing. A complete decapitation at the neck is held back in place with a linen band. There is resin patched into fractured vertebrae. The left shoulder is dislocated, but wrapped in place. Only three fingers remain. A defect in the abdominal wall is patched with linen treated in resin, with two amulets underneath.

One conclusion of a report published Monday in the peer-reviewed Frontiers in Medicine is that this physical disruption, probably in two separate rewrappings by priests of the 21st Dynasty after 1100 BC, reflects an effort to protect and preserve this king’s body after grave robbery, because by then he was the subject of an important funerary cult.

The location of the damage at the neck and limbs lend credence to the view that tomb raiders were after jewelry, and “hacked the abdomen wall in search of amulets inside the body cavity,” according to the report.

Lead author Sahar Saleem, an Egyptian radiologist who has previously scanned the body of King Tutankhamun and found a knife wound in the throat of Ramesses III, suggestive of murder, told the National Post on Monday from Cairo that “unwrapping” Amenhotep I’s earthly remains without disturbing them was “like the thrill one gets unwrapping a gift.”

Saleem, who started her career in paleoradiology while studying medicine at Western University in Ontario before joining Egypt’s Ministry of Antiquities in 2006, said this is the latest of the 40 mummies she has scanned since 2005. Her co-author is Zahi Hawass, an Egyptologist who also served as minister of antiquities under Hosni Mubarak.

Scanning the mummy of Amenhotep I is a special opportunity. It is the only royal mummy that has not been physically unwrapped in modern times. This is due to its unique “beauty and perfect preservation,” Saleem said, with obsidian crystals in the eyes on the face mask, a carved cobra on the forehead with inlaid stones, and floral garlands draping down.

Amenhotep I was a king in the 18th Dynasty who succeeded his father as a boy in 1525 BCE and ruled for 21 years, leading military campaigns and building important structures including a temple at Karnak.

The famous Egyptian Book of the Dead, the body of writing that describes the Egyptian afterlife and is often found on papyrus scrolls ceremonially entombed with royals, is thought to have been completed in his reign, as it first appears in the tomb of his successor.

Amenhotep I was the first pharaoh to build a tomb separate from a mortuary temple, possibly to deter grave robbers. This set a new burial trend and made him the subject of a funerary cult, with many statues found in his likeness and records of feast days.

His coffin was moved and reburied by priests of the 21st Dynasty, four centuries after his death, and ended up in the great royal cache at Deir-al-Bahri, a disorganized collection of royal mummies, with some even in others’ coffins.

Amenhotep I was discovered there in 1881, in a coffin that detailed in hieroglyphs the efforts of priests to rewrap the mummy after damage by grave robbers.

“Gaston Maspero, the director of antiquities in Egypt at that time, decided to let the mummy remain untouched because of its perfect wrapping completely covered by garlands and its exquisite face mask,” the paper reports. “When the coffin of Amenhotep I was opened, a preserved wasp was found, possibly attracted by the smell of garlands, and was trapped.”

“This study may make us gain confidence in the goodwill of the reburial project of the Royal mummies by the 21st dynasty priests,” it says.

Saleem said CT scanning can answer or inform nearly every question about a mummy, including age, sex, health, diseases, cause of death, style of mummification, artifacts, and so on. But there remain questions about the chemistry of embalming materials, which newer developments in CT imaging might help with.

The scan revealed that amulets of scarabs, snails, serpent heads and the Eye of Horus in gold, clay and stone were arranged around the body

Author of the article:Joseph Brean

Publishing date:Dec 28, 2021 •

A computed tomography scan of the face of the Egyptian pharaoh Amenhotep I,

who died in 1504 BCE

PHOTO BY SAHAR SALEEM AND ZAHI HAWASS

Undisturbed for three millennia, the last unwrapped pharaonic mummy has given up secrets to the modern science of computed tomography. A new scan reveals an amulet over the heart of Amenhotep I, a girdle of 34 golden beads at his lower back, and evidence that his earthly remains were damaged and fixed up by ancient Egyptian priests four centuries after his death in 1504 BCE.

Undisturbed for three millennia, the last unwrapped pharaonic mummy has given up secrets to the modern science of computed tomography. A new scan reveals an amulet over the heart of Amenhotep I, a girdle of 34 golden beads at his lower back, and evidence that his earthly remains were damaged and fixed up by ancient Egyptian priests four centuries after his death in 1504 BCE.

The CT scan also produced an image of his face, revealing a slightly bucktoothed 35-year-old man with a narrow chin, sunken cheeks, small eyes and a pierced left ear. His brain remains in place, shrivelled onto the back of his skull. He was circumcised. Amulets of scarabs, snails, serpent heads and the Eye of Horus in gold, clay and stone are arranged around the body. There is an incision on his left flank through which he was eviscerated. Alive, he was short, probably about five foot six and a bit, and he is now the earliest known mummy of the New Kingdom golden age of Egyptian pharaohs whose arms are crossed at the chest.

No cause of death was obvious, but postmortem damage was revealing. A complete decapitation at the neck is held back in place with a linen band. There is resin patched into fractured vertebrae. The left shoulder is dislocated, but wrapped in place. Only three fingers remain. A defect in the abdominal wall is patched with linen treated in resin, with two amulets underneath.

One conclusion of a report published Monday in the peer-reviewed Frontiers in Medicine is that this physical disruption, probably in two separate rewrappings by priests of the 21st Dynasty after 1100 BC, reflects an effort to protect and preserve this king’s body after grave robbery, because by then he was the subject of an important funerary cult.

The location of the damage at the neck and limbs lend credence to the view that tomb raiders were after jewelry, and “hacked the abdomen wall in search of amulets inside the body cavity,” according to the report.

Lead author Sahar Saleem, an Egyptian radiologist who has previously scanned the body of King Tutankhamun and found a knife wound in the throat of Ramesses III, suggestive of murder, told the National Post on Monday from Cairo that “unwrapping” Amenhotep I’s earthly remains without disturbing them was “like the thrill one gets unwrapping a gift.”

Saleem, who started her career in paleoradiology while studying medicine at Western University in Ontario before joining Egypt’s Ministry of Antiquities in 2006, said this is the latest of the 40 mummies she has scanned since 2005. Her co-author is Zahi Hawass, an Egyptologist who also served as minister of antiquities under Hosni Mubarak.

Scanning the mummy of Amenhotep I is a special opportunity. It is the only royal mummy that has not been physically unwrapped in modern times. This is due to its unique “beauty and perfect preservation,” Saleem said, with obsidian crystals in the eyes on the face mask, a carved cobra on the forehead with inlaid stones, and floral garlands draping down.

Amenhotep I was a king in the 18th Dynasty who succeeded his father as a boy in 1525 BCE and ruled for 21 years, leading military campaigns and building important structures including a temple at Karnak.

The famous Egyptian Book of the Dead, the body of writing that describes the Egyptian afterlife and is often found on papyrus scrolls ceremonially entombed with royals, is thought to have been completed in his reign, as it first appears in the tomb of his successor.

Amenhotep I was the first pharaoh to build a tomb separate from a mortuary temple, possibly to deter grave robbers. This set a new burial trend and made him the subject of a funerary cult, with many statues found in his likeness and records of feast days.

His coffin was moved and reburied by priests of the 21st Dynasty, four centuries after his death, and ended up in the great royal cache at Deir-al-Bahri, a disorganized collection of royal mummies, with some even in others’ coffins.

Amenhotep I was discovered there in 1881, in a coffin that detailed in hieroglyphs the efforts of priests to rewrap the mummy after damage by grave robbers.

“Gaston Maspero, the director of antiquities in Egypt at that time, decided to let the mummy remain untouched because of its perfect wrapping completely covered by garlands and its exquisite face mask,” the paper reports. “When the coffin of Amenhotep I was opened, a preserved wasp was found, possibly attracted by the smell of garlands, and was trapped.”

“This study may make us gain confidence in the goodwill of the reburial project of the Royal mummies by the 21st dynasty priests,” it says.

Saleem said CT scanning can answer or inform nearly every question about a mummy, including age, sex, health, diseases, cause of death, style of mummification, artifacts, and so on. But there remain questions about the chemistry of embalming materials, which newer developments in CT imaging might help with.

No comments:

Post a Comment