Bernie Sanders to join striking workers in Battle Creek as political pressure on Kellogg increases

Norah Mulinda, Bloomberg

and Josh Funk, Associated Press

Rey Del Rio/Getty Images via Bloomberg

Kellogg's cereal plant workers demonstrate in front of the cereal plant in Battle Creek in October.

Sen. Bernie Sanders plans to rally with striking Kellogg Co. workers in Battle Creek on Friday, highlighting an issue that also has drawn the attention of President Joe Biden.

Kellogg is facing increasing political pressure to resume contract talks with its 1,400 cereal plant workers who walked out Oct. 5.

Bernie Sanders

Sanders, a former Democratic presidential candidate, heads to Michigan after Kellogg said last month it was planning to hire replacement workers "where appropriate."

"Kellogg's workers made the company billions during a pandemic by working 12-hour shifts, some for more than 100 days in a row," Sanders said in a tweet Tuesday. The company is "now choosing corporate greed over the workers they once called 'heroes'."

Last week, Biden said he was "troubled" by Kellogg's plan to replace the striking workers and urged the two sides to reach an agreement.

Meanwhile, Nebraska Gov. Pete Ricketts sent a letter to the company's CEO this week urging the company to return to the bargaining table with workers at its four plants nationwide, including one in his state.

Ricketts said in his letter that the Battle Creek-based company should recognize the contributions its workers have made during the pandemic by continuing to produce its well-known brands of cereal and try to retain them during this period when many companies are struggling to hire enough workers.

"Despite the challenges of the global pandemic, they showed up day after day to do their jobs so that across the country there was food on the shelves," said Ricketts, a Republican. "These workers helped Kellogg's increase sales and revenue (and grow net income by over 30 percent) from 2019 to 2020 — a time when many businesses endured losses due to the financial headwinds of the pandemic."

Michigan Gov. Gretchen Whitmer, a Democrat, has not publicly weighed in on the work stoppage.

Members of the Bakery, Confectionery, Tobacco Workers and Grain Millers International Union overwhelmingly rejected a contract offer from the company last week that would have delivered 3 percent raises and preserved their current health benefits.

Union members have said they remain concerned about the company's two-tiered system of wages that has been a sticking point during contract talks. The company said its offer would have allowed all workers with at least four years of experience move up to the higher legacy pay level, but union officials said the plan wouldn't let other workers move up quickly enough. And the company proposed eliminating the current 30 percent cap on the number of workers at each plant who receive those lower wages.

Biden said in a statement Friday he believes Kellogg was undermining the collective bargaining process with its plan to hire permanent replacements for the striking workers.

"I am deeply troubled by reports of Kellogg's plans to permanently replace striking workers from the Bakery, Confectionery, Tobacco Workers and Grain Millers International during their ongoing collective bargaining negotiations," said Biden, the Democrat who has long been a strong supporter of unions. "Permanently replacing striking workers is an existential attack on the union and its members' jobs and livelihoods."

Throughout the strike, Kellogg has been trying to keep its plants operating with salaried employees and outside workers, but it said after the contract vote that it would move forward with plans to hire permanent replacements.

Kellogg spokeswoman Kris Bahner said the company believes its contract offers have been fair and it remains willing to negotiate with the union although no additional talks are scheduled at the moment. She said last week's offer would have improved workers' wages and benefits.

"We are very disappointed that it was ultimately rejected. We have an obligation to our customers and consumers to continue to provide the cereals that they know and love — as well as to the thousands of people we employ," Bahner said.

The strike includes four plants in Battle Creek; Omaha, Neb.; Lancaster, Pa.; and Memphis, Tenn., that make all of Kellogg's brands of cereal, including Rice Krispies and Apple Jacks.

Norah Mulinda, Bloomberg

and Josh Funk, Associated Press

Rey Del Rio/Getty Images via Bloomberg

Kellogg's cereal plant workers demonstrate in front of the cereal plant in Battle Creek in October.

Sen. Bernie Sanders plans to rally with striking Kellogg Co. workers in Battle Creek on Friday, highlighting an issue that also has drawn the attention of President Joe Biden.

Kellogg is facing increasing political pressure to resume contract talks with its 1,400 cereal plant workers who walked out Oct. 5.

Bernie Sanders

Sanders, a former Democratic presidential candidate, heads to Michigan after Kellogg said last month it was planning to hire replacement workers "where appropriate."

"Kellogg's workers made the company billions during a pandemic by working 12-hour shifts, some for more than 100 days in a row," Sanders said in a tweet Tuesday. The company is "now choosing corporate greed over the workers they once called 'heroes'."

Last week, Biden said he was "troubled" by Kellogg's plan to replace the striking workers and urged the two sides to reach an agreement.

Meanwhile, Nebraska Gov. Pete Ricketts sent a letter to the company's CEO this week urging the company to return to the bargaining table with workers at its four plants nationwide, including one in his state.

Ricketts said in his letter that the Battle Creek-based company should recognize the contributions its workers have made during the pandemic by continuing to produce its well-known brands of cereal and try to retain them during this period when many companies are struggling to hire enough workers.

"Despite the challenges of the global pandemic, they showed up day after day to do their jobs so that across the country there was food on the shelves," said Ricketts, a Republican. "These workers helped Kellogg's increase sales and revenue (and grow net income by over 30 percent) from 2019 to 2020 — a time when many businesses endured losses due to the financial headwinds of the pandemic."

Michigan Gov. Gretchen Whitmer, a Democrat, has not publicly weighed in on the work stoppage.

Members of the Bakery, Confectionery, Tobacco Workers and Grain Millers International Union overwhelmingly rejected a contract offer from the company last week that would have delivered 3 percent raises and preserved their current health benefits.

Union members have said they remain concerned about the company's two-tiered system of wages that has been a sticking point during contract talks. The company said its offer would have allowed all workers with at least four years of experience move up to the higher legacy pay level, but union officials said the plan wouldn't let other workers move up quickly enough. And the company proposed eliminating the current 30 percent cap on the number of workers at each plant who receive those lower wages.

Biden said in a statement Friday he believes Kellogg was undermining the collective bargaining process with its plan to hire permanent replacements for the striking workers.

"I am deeply troubled by reports of Kellogg's plans to permanently replace striking workers from the Bakery, Confectionery, Tobacco Workers and Grain Millers International during their ongoing collective bargaining negotiations," said Biden, the Democrat who has long been a strong supporter of unions. "Permanently replacing striking workers is an existential attack on the union and its members' jobs and livelihoods."

Throughout the strike, Kellogg has been trying to keep its plants operating with salaried employees and outside workers, but it said after the contract vote that it would move forward with plans to hire permanent replacements.

Kellogg spokeswoman Kris Bahner said the company believes its contract offers have been fair and it remains willing to negotiate with the union although no additional talks are scheduled at the moment. She said last week's offer would have improved workers' wages and benefits.

"We are very disappointed that it was ultimately rejected. We have an obligation to our customers and consumers to continue to provide the cereals that they know and love — as well as to the thousands of people we employ," Bahner said.

The strike includes four plants in Battle Creek; Omaha, Neb.; Lancaster, Pa.; and Memphis, Tenn., that make all of Kellogg's brands of cereal, including Rice Krispies and Apple Jacks.

Michelle Cheng

Wed, December 15, 2021

Striking Kellogg workers picket outside a plant in Michigan

In a tight US labor market, unionized workers have been demanding more. But labor is perhaps starting to lose the upper hand.

Following the failure to reach a contract with its union, Kellogg’s said it is permanently replacing striking workers. Some 1,400 hourly employees, who are part of the Bakery, Confectionary, Tobacco Workers and Grain Millers International Union, walked off the job across four cereal plants in Michigan, Nebraska, Pennsylvania, and Tennessee starting Oct. 5.

The rejected contract offer would have included a 3% wage hike for legacy employees and increases for newer hires. The company proposed eliminating the cap on the share of lower-tier workers, but some union employees were worried that would put downward pressure on veteran workers’ wages if lower-tier workers became a majority.

The food manufacturer has been on a hiring spree to replace the striking workers. The hourly rates for replacement workers posted on the Kellogg’s job board are $21.72 an hour for “general labor” and $34 to $37 for “skilled labor”, depending on the role. That’s comparable to the pay for the unionized legacy employees, who make on average $35.26 an hour, according to Kris Bahner, a company spokesperson.

The fact that the replacement wages are more or less the same as the previous pay suggests the labor market may not be as tight as union activists believe.

The unemployment rate in Battle Creek, Michigan is worse than the US average

In Battle Creek, Michigan, where Kellogg’s is headquartered, the labor situation has been challenging.

The unemployment rate in the city was 6% in October, which is higher than the national average of 4.6%, according to data from the US Bureau of Labor Statistics. The job opening rate, or the share of available jobs of all filled and unfilled positions, in the nondurable good industry—which includes Kellogg’s, one of the largest employers in the city—was 8%, higher than the national average of 6.9%. Meanwhile, the hourly earnings of all private-sector workers in Battle Creek was $26.22 in October, suggesting that Kellogg’s workers are highly compensated compared to the relative jobs in the area. That may boost the company’s confidence it will find workers to replace the ones striking, and undermine the union’s bargaining power.

“There’s a lot of potential labor supply for these jobs,” says Donald Grimes, a regional economic specialist at University of Michigan. “The idea that people are not going to take these replacement jobs is a bit inaccurate.”

Still, while the pay is high, it’s possible Kellogg’s is bluffing, Ruth Milkman, a professor at the City University of New York’s School of Labor and Urban Studies, wrote in an email. She said that while permanently replacing striking workers is both standard operating procedure and legal, recent strikes have not seen this outcome because it’s hard to find workers.

Labor resurgence?

From Nabisco to Amazon, the heightened labor activity in part stems from the pandemic, which has forced workers into more unsafe working conditions or less favorable schedules. Meanwhile, lower-wage workers, like those in the restaurant or retail industry, have been quitting at record rates, signaling that they feel confident they can find better jobs elsewhere—and can do so without a union.

But there are reasons to think that Kellogg’s union should have perhaps taken the deal.

The union may have had confidence its workers would not want to cross the picket line, but it’s not clear if that will be the case since the region’s unemployment rate is high and wages for Kellogg’s workers are better than the average job in the area. “I would just be a little bit careful if I was on the high end of the payscale if I was a union member,” says Grimes. “You could go overboard.”

And, despite most Americans supporting unions, union enrollment has been on a decline for decades. Just 10.8% of US employees are part of unions, according to the latest BLS data. Part of the reason for that is just how organizations have become more fragmented, according to Grimes. He adds, an increasingly larger share of jobs are in industries that have smaller firms, and it’s just harder to unionize smaller shops.

The bakery union still represents tens of thousands of workers at other companies, but the risk for striking workers is not just other workers filling their spots but also more investment in robots and automation to replace those workers, says Grimes. It’s possible that even if Kellogg’s union workers win this battle, they could still lose the war.

Ken Klippenstein discusses demands of striking Kellogg workers

12/15/2021

Investigative reporter Ken Klippenstein on Monday delved into the demands of striking Kellogg workers, as well as the company's reaction to their efforts.

In an interview on Hill TV's "Rising," Klippenstein, who has been covering the strike, said he is hearing frustration from workers that "management was getting its side of the story across" more successfully. He noted that the company is "calling in over 1,000" replacement workers and "looking to hire them permanently."

Last week, Kellogg North America President Chris Hood said the company would need to move forward its regular operations after having 19 negotiation sessions with striking workers.

About two months ago, roughly 1,440 Kellogg employees began striking when the company and their union, the Bakery, Confectionery, Tobacco Workers and Grain Millers International Union, had a contract dispute.

After the employees rejected a proposed five-year contract, Hood said that Kellogg had "no choice but to continue executing the next phase of our contingency plan including hiring replacement employees in positions vacated by striking workers."

During his interview, Klippenstein said such a decision is "something that's illegal in a lot of countries."

He said the employees "voted against a proposal from the company which would set up a two track pay system wherein new hires, new employees would not enjoy the same benefits which not only senior employees had enjoyed but junior ones in the past historically had been given."

"This strike really is an act of sympathy from the older workers who want there to be one pay system partly out of solidarity with the younger workers but also because they recognize that setting up a two track pay system has a sort of downward and depressing effect on their wages at the top too," he said.

12/15/2021

Investigative reporter Ken Klippenstein on Monday delved into the demands of striking Kellogg workers, as well as the company's reaction to their efforts.

In an interview on Hill TV's "Rising," Klippenstein, who has been covering the strike, said he is hearing frustration from workers that "management was getting its side of the story across" more successfully. He noted that the company is "calling in over 1,000" replacement workers and "looking to hire them permanently."

Last week, Kellogg North America President Chris Hood said the company would need to move forward its regular operations after having 19 negotiation sessions with striking workers.

About two months ago, roughly 1,440 Kellogg employees began striking when the company and their union, the Bakery, Confectionery, Tobacco Workers and Grain Millers International Union, had a contract dispute.

After the employees rejected a proposed five-year contract, Hood said that Kellogg had "no choice but to continue executing the next phase of our contingency plan including hiring replacement employees in positions vacated by striking workers."

During his interview, Klippenstein said such a decision is "something that's illegal in a lot of countries."

He said the employees "voted against a proposal from the company which would set up a two track pay system wherein new hires, new employees would not enjoy the same benefits which not only senior employees had enjoyed but junior ones in the past historically had been given."

"This strike really is an act of sympathy from the older workers who want there to be one pay system partly out of solidarity with the younger workers but also because they recognize that setting up a two track pay system has a sort of downward and depressing effect on their wages at the top too," he said.

Striking Kellogg’s Workers Vow to Hold Out for Better Contract, Urge Boycott of Company Products

What workers are striking against: A global profile of the Kellogg Company

Tom Hall

WSWS.ORG

“The pandemic presented us with a sampling event like none other and we saw increases in household penetration that outpaced most of our categories...” This is how Kellogg’s CEO Steve Cahillane summed up the company’s performance during 2020, when widespread lockdowns drove demand for packaged foods as millions sheltered in their own homes. Net income for the breakfast cereal giant increased 30 percent to $1.25 billion, and revenue jumped slightly to $13.77 billion.

This rosy description of the coronavirus pandemic, which has killed 800,000 in the US alone, is an example of the cold logic driving forward the company’s attempts to smash the two-month strike by 1,400 cereal workers in the United States. It responded to their overwhelming rejection of a concessions contract brokered by the Bakery, Confectionery, Tobacco Workers and Grain Millers’ International Union (BCTGM)—that would have eliminated restrictions on the hiring of lower-paid, second tier workers—by declaring it would accelerate plans to fire and replace the strikers en masse. This autocratic move sparked outrage among workers around the country and the world.

Tom Hall

WSWS.ORG

“The pandemic presented us with a sampling event like none other and we saw increases in household penetration that outpaced most of our categories...” This is how Kellogg’s CEO Steve Cahillane summed up the company’s performance during 2020, when widespread lockdowns drove demand for packaged foods as millions sheltered in their own homes. Net income for the breakfast cereal giant increased 30 percent to $1.25 billion, and revenue jumped slightly to $13.77 billion.

This rosy description of the coronavirus pandemic, which has killed 800,000 in the US alone, is an example of the cold logic driving forward the company’s attempts to smash the two-month strike by 1,400 cereal workers in the United States. It responded to their overwhelming rejection of a concessions contract brokered by the Bakery, Confectionery, Tobacco Workers and Grain Millers’ International Union (BCTGM)—that would have eliminated restrictions on the hiring of lower-paid, second tier workers—by declaring it would accelerate plans to fire and replace the strikers en masse. This autocratic move sparked outrage among workers around the country and the world.

Kellogg World Headquarters, Battle Creek, Michigan, USA (source: Wikpedia)

But this ruthless campaign is not the product of a company struggling for survival. Indeed, Kellogg’s remains as highly profitable as it has been in its more than 110-year history, and it has expanded its operations significantly in recent years, driven by ruthless cost-cutting. Indeed, breakfast cereal is among the most profitable segments in the food processing industry, which Yahoo! in turn recently rated the 14th most profitable industry in the world.

In 1995, when the International Committee initiated a campaign against Kellogg’s global job-cutting campaign at the time, we noted that Kellogg’s had already vastly increased its international scope. Of its global workforce of 15,000 at the time, 7,000 lived outside of the United States, and the company was expanding aggressively into emerging markets such as southeast Asia and the former Soviet Union. The company had made $705 million in net profits the year before, on worldwide sales of $6.6 billion.

At the same time, the company controlled 42 percent of the global cereal market and was locked in a bitter struggle over market share with rival General Mills.

Since then, both the company’s revenue and profits have roughly doubled. Kellogg’s earnings before interest and taxes (EBIT) were $1.6 billion, with an 11.6 percent profit margin. By comparison, Ford Motor Company reported of $1.63 billion on $115.8 billion in revenue, making the world’s fourth-largest auto manufacturer slightly more than one-tenth as profitable as Kellogg’s.

Dividends, meanwhile, have increased for decades, and now stand at $2.31 cents a share. At a share value of $63.37, this means Kellogg’s dividend yield is 3.5 percent, more than twice the average of the S&P 500. Even though many other large companies suspended dividend payments last year to conserve cash during the pandemic, Kellogg’s continued to dole out tens of millions of dollars to its shareholders.

A globalized food company

In spite of this, Kellogg’s market share in breakfast cereals has continuously eroded since the 1990s. Its US market share declined from 36 percent in 1995 to 30 percent in 2017. This is one factor in the company’s growing diversification into different segments of the prepared foods market. It has done this through a series of high-profile mergers and acquisitions that will continue to play a critical role in the company’s current “Deploy for Growth” strategy, which targets accelerated growth rates of between 1 and 3 percent.

But this ruthless campaign is not the product of a company struggling for survival. Indeed, Kellogg’s remains as highly profitable as it has been in its more than 110-year history, and it has expanded its operations significantly in recent years, driven by ruthless cost-cutting. Indeed, breakfast cereal is among the most profitable segments in the food processing industry, which Yahoo! in turn recently rated the 14th most profitable industry in the world.

In 1995, when the International Committee initiated a campaign against Kellogg’s global job-cutting campaign at the time, we noted that Kellogg’s had already vastly increased its international scope. Of its global workforce of 15,000 at the time, 7,000 lived outside of the United States, and the company was expanding aggressively into emerging markets such as southeast Asia and the former Soviet Union. The company had made $705 million in net profits the year before, on worldwide sales of $6.6 billion.

At the same time, the company controlled 42 percent of the global cereal market and was locked in a bitter struggle over market share with rival General Mills.

Since then, both the company’s revenue and profits have roughly doubled. Kellogg’s earnings before interest and taxes (EBIT) were $1.6 billion, with an 11.6 percent profit margin. By comparison, Ford Motor Company reported of $1.63 billion on $115.8 billion in revenue, making the world’s fourth-largest auto manufacturer slightly more than one-tenth as profitable as Kellogg’s.

Dividends, meanwhile, have increased for decades, and now stand at $2.31 cents a share. At a share value of $63.37, this means Kellogg’s dividend yield is 3.5 percent, more than twice the average of the S&P 500. Even though many other large companies suspended dividend payments last year to conserve cash during the pandemic, Kellogg’s continued to dole out tens of millions of dollars to its shareholders.

A globalized food company

In spite of this, Kellogg’s market share in breakfast cereals has continuously eroded since the 1990s. Its US market share declined from 36 percent in 1995 to 30 percent in 2017. This is one factor in the company’s growing diversification into different segments of the prepared foods market. It has done this through a series of high-profile mergers and acquisitions that will continue to play a critical role in the company’s current “Deploy for Growth” strategy, which targets accelerated growth rates of between 1 and 3 percent.

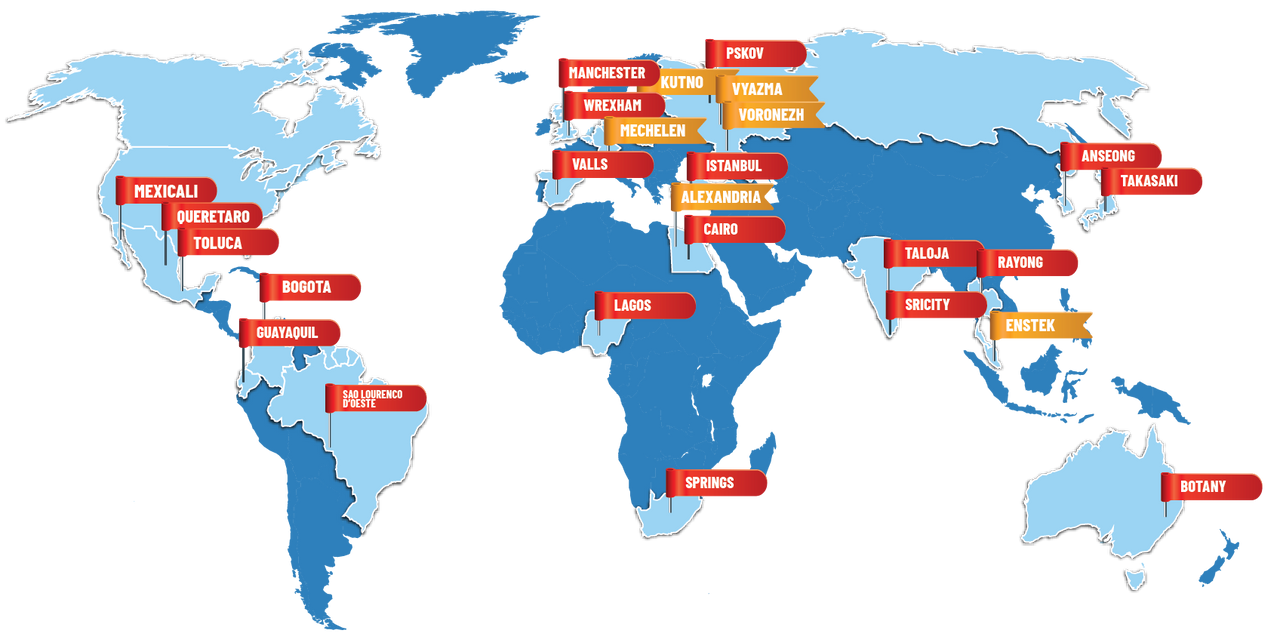

Map of Kellogg's international factories (source: Kellogg's)

These mergers have expanded Kellogg’s from a cereal maker primarily centered around on the US market to a multinational producing a wide variety of packaged foods for different markets across the world. The most high profile of these acquisitions was arguably its $2.7 billion purchase of potato chip brand Pringles in 2012 from Proctor & Gamble. Most of its recent acquisitions, however, have focused on international brands and joint ventures.

These include:

A joint venture announced in 2012 with Singapore-based Wilmar International focused on the growing Chinese snack market;

Another joint ventured in 2015 with Tolaram Africa focused on West Africa. Kellogg’s later invested another $420 million into the venture;

The purchase of majority stakes in Egyptian food companies Bisco Misr and Mass Food Group, also in 2015;

A 2016 acquisition of a controlling stake in Brazilian food company Parati for $429 million

As a result of these moves, breakfast cereals occupy a substantially smaller portion of the company’s sales than it did less than 20 years ago. According to a 2018 slide show for investors, the proportion of cereal as a total of net sales declined from roughly two-thirds in 2005 to less than half in 2017, while snacks, a category that includes products such as Cheezits, Pringles, Town House crackers and Nutri-grain bars, doubled to 52 percent. The volume of products sold in the United States as a share of worldwide also declined in this period.

The company’s workforce has also doubled since 1995 to approximately 30,000 today. Currently, it operates 52 plants worldwide, half of which are located outside of North America. These include three plants in Russia, three in South America, three in Africa and two in India. Slightly less than half, or 25 of these plants, actually produce cereal, with others producing frozen foods and pre-packaged snacks. Only five of the company’s 26 factories in the US and Canada, four of which are involved in the current strike, produce cereal (the fifth, a new plant located in Belleville, Canada, is not a party to the same labor contract as the US plants).

The 1,400 workers on strike in the four US cereal plants comprise less than five percent of Kellogg’s the global workforce. This is, in part, the product of relentless job-cutting campaigns, such as the one in 1995 that eliminated 1,075 jobs worldwide. The cuts have reduced the workforce of these plants to a fraction of what they were a generation ago. The company’s flagship plant in Battle Creek, Michigan currently employs only 410 workers, less than a quarter of the 1,700 people who worked there in 1995.

These mergers have expanded Kellogg’s from a cereal maker primarily centered around on the US market to a multinational producing a wide variety of packaged foods for different markets across the world. The most high profile of these acquisitions was arguably its $2.7 billion purchase of potato chip brand Pringles in 2012 from Proctor & Gamble. Most of its recent acquisitions, however, have focused on international brands and joint ventures.

These include:

A joint venture announced in 2012 with Singapore-based Wilmar International focused on the growing Chinese snack market;

Another joint ventured in 2015 with Tolaram Africa focused on West Africa. Kellogg’s later invested another $420 million into the venture;

The purchase of majority stakes in Egyptian food companies Bisco Misr and Mass Food Group, also in 2015;

A 2016 acquisition of a controlling stake in Brazilian food company Parati for $429 million

As a result of these moves, breakfast cereals occupy a substantially smaller portion of the company’s sales than it did less than 20 years ago. According to a 2018 slide show for investors, the proportion of cereal as a total of net sales declined from roughly two-thirds in 2005 to less than half in 2017, while snacks, a category that includes products such as Cheezits, Pringles, Town House crackers and Nutri-grain bars, doubled to 52 percent. The volume of products sold in the United States as a share of worldwide also declined in this period.

The company’s workforce has also doubled since 1995 to approximately 30,000 today. Currently, it operates 52 plants worldwide, half of which are located outside of North America. These include three plants in Russia, three in South America, three in Africa and two in India. Slightly less than half, or 25 of these plants, actually produce cereal, with others producing frozen foods and pre-packaged snacks. Only five of the company’s 26 factories in the US and Canada, four of which are involved in the current strike, produce cereal (the fifth, a new plant located in Belleville, Canada, is not a party to the same labor contract as the US plants).

The 1,400 workers on strike in the four US cereal plants comprise less than five percent of Kellogg’s the global workforce. This is, in part, the product of relentless job-cutting campaigns, such as the one in 1995 that eliminated 1,075 jobs worldwide. The cuts have reduced the workforce of these plants to a fraction of what they were a generation ago. The company’s flagship plant in Battle Creek, Michigan currently employs only 410 workers, less than a quarter of the 1,700 people who worked there in 1995.

Kellogg's plant in Querétaro, Mexico (source: Kellogg's)

Kellogg’s global workforce has been subjected to repeated job cuts. The most recent of these, “Project K” which was completed just before the pandemic in 2019, eliminated 7 percent of the global workforce, resulting in an estimated cost savings of $700 million per year, according to the company.

At the same time, Kellogg’s has demanded repeated concessions from workers’ wages and benefits, supposedly in the name of “saving” jobs. Before and during the 2015 contract talks, it locked out workers at the Memphis plant and threatened to close an unnamed US plant if workers did not accept the establishment of a new second tier of lower-paid “transitional” workers. The BCTGM obliged, pushing the contract through, but its repeated acceptance of concessions has not saved a single job.

In part to deflect attention from this record, the BCTGM is promoting a ferocious anti-Mexican campaign, calling on Kellogg’s and other companies to cease production in Mexico and blaming foreign workers for the loss of jobs and wages in the United States. This racist agitation has been taken up by the far-right news outlet Breitbart, which is a key media promoter of Trump’s ongoing attempts to build a fascist, extra-constitutional movement. In fact, Trump’s nationalist “America First” tirades, directed against Mexico in particular, had been the stock in trade of the American unions for decades before Trump emerged as a major political figure in the Republican Party.

In reality, Kellogg’s presence in Mexico goes back decades, and it was the first non-English speaking market that the company expanded into. The Kellogg’s plant in Queretaro, Mexico was built in 1951, making it decades older than the US plant in Lancaster, Pennsylvania.

While the company has, almost from the start, conducted business on a multinational scale, the international expansion of Kellogg’s and the global integration of capitalist production over the past four decades has rendered the national-based strategy of the BCTGM, and indeed the trade unions as a whole, hopelessly obsolete. It serves only to isolate the striking workers in the United States from their most powerful allies in Kellogg’s global workforce and the international working class as a whole, all of whom would be outraged to learn of the company’s strikebreaking efforts. Indeed, Kellogg’s is attempting to weather the strike by utilizing its international supply chains to compensate for lost production in the United States.

Kellogg’s global workforce has been subjected to repeated job cuts. The most recent of these, “Project K” which was completed just before the pandemic in 2019, eliminated 7 percent of the global workforce, resulting in an estimated cost savings of $700 million per year, according to the company.

At the same time, Kellogg’s has demanded repeated concessions from workers’ wages and benefits, supposedly in the name of “saving” jobs. Before and during the 2015 contract talks, it locked out workers at the Memphis plant and threatened to close an unnamed US plant if workers did not accept the establishment of a new second tier of lower-paid “transitional” workers. The BCTGM obliged, pushing the contract through, but its repeated acceptance of concessions has not saved a single job.

In part to deflect attention from this record, the BCTGM is promoting a ferocious anti-Mexican campaign, calling on Kellogg’s and other companies to cease production in Mexico and blaming foreign workers for the loss of jobs and wages in the United States. This racist agitation has been taken up by the far-right news outlet Breitbart, which is a key media promoter of Trump’s ongoing attempts to build a fascist, extra-constitutional movement. In fact, Trump’s nationalist “America First” tirades, directed against Mexico in particular, had been the stock in trade of the American unions for decades before Trump emerged as a major political figure in the Republican Party.

In reality, Kellogg’s presence in Mexico goes back decades, and it was the first non-English speaking market that the company expanded into. The Kellogg’s plant in Queretaro, Mexico was built in 1951, making it decades older than the US plant in Lancaster, Pennsylvania.

While the company has, almost from the start, conducted business on a multinational scale, the international expansion of Kellogg’s and the global integration of capitalist production over the past four decades has rendered the national-based strategy of the BCTGM, and indeed the trade unions as a whole, hopelessly obsolete. It serves only to isolate the striking workers in the United States from their most powerful allies in Kellogg’s global workforce and the international working class as a whole, all of whom would be outraged to learn of the company’s strikebreaking efforts. Indeed, Kellogg’s is attempting to weather the strike by utilizing its international supply chains to compensate for lost production in the United States.

Kellogg's facility in Lagos, Nigeria (source: user on Nairaland messageboard)

But the international dimensions of Kellogg’s operations are a source of strength for workers, not weakness. Kellogg’s, like any other major international company, is extremely vulnerable to disruptions in its global supply chains and a global campaign among Kellogg’s workers to unite with workers in the US would have a powerful impact.

Workers in Mexico have repeatedly demonstrated their determination to oppose their exploitation. In January 2019, auto parts and electronics workers in Matamoros, just across the border from Brownsville, Texas revolted against the poverty wages and sweatshop conditions at the US and other foreign-owned maquiladoras. They staged a series of wildcat strikes in defiance of the company-controlled unions and marched to the border where they appealed to their class brothers and sisters in the US to join them.

In the summer and fall of 2019, workers at the General Motors factory in Silao, Mexico refused to work overtime during the strike by 45,000 GM workers in the US. For their courageous act of class solidarity, GM fired and blacklisted the leaders of the struggle. In response, rank-and-file workers in the US called for their reinstatement and donated money to support the victimized Mexican workers.

The American media, the BCTGM, the United Auto Workers and other US unions blacked out any information about these struggles in order to keep perpetuating the poisonous lie that Mexican and American workers are enemies.

Among striking Kellogg’s workers in the US there is enormous sympathy for their coworkers in Mexico and the developing world, whom they regard as a super-exploited “third tier” of workers.

Kellogg’s has an international strategy to pit workers against each other in a race to the bottom. To defeat this, workers need their own international strategy. That means rejecting the divide-and-conquer nationalism promoted by the BCTGM and reaching out to their class brothers and sisters around the world to defend the jobs, living standards and working conditions of all workers.

This requires taking the conduct of the strike out of the hands of the pro-company union by establishing a rank-and-file strike committee, independent of the BCTGM, to establish lines of communication and joint action by workers across Kellogg’s global empire.

But the international dimensions of Kellogg’s operations are a source of strength for workers, not weakness. Kellogg’s, like any other major international company, is extremely vulnerable to disruptions in its global supply chains and a global campaign among Kellogg’s workers to unite with workers in the US would have a powerful impact.

Workers in Mexico have repeatedly demonstrated their determination to oppose their exploitation. In January 2019, auto parts and electronics workers in Matamoros, just across the border from Brownsville, Texas revolted against the poverty wages and sweatshop conditions at the US and other foreign-owned maquiladoras. They staged a series of wildcat strikes in defiance of the company-controlled unions and marched to the border where they appealed to their class brothers and sisters in the US to join them.

In the summer and fall of 2019, workers at the General Motors factory in Silao, Mexico refused to work overtime during the strike by 45,000 GM workers in the US. For their courageous act of class solidarity, GM fired and blacklisted the leaders of the struggle. In response, rank-and-file workers in the US called for their reinstatement and donated money to support the victimized Mexican workers.

The American media, the BCTGM, the United Auto Workers and other US unions blacked out any information about these struggles in order to keep perpetuating the poisonous lie that Mexican and American workers are enemies.

Among striking Kellogg’s workers in the US there is enormous sympathy for their coworkers in Mexico and the developing world, whom they regard as a super-exploited “third tier” of workers.

Kellogg’s has an international strategy to pit workers against each other in a race to the bottom. To defeat this, workers need their own international strategy. That means rejecting the divide-and-conquer nationalism promoted by the BCTGM and reaching out to their class brothers and sisters around the world to defend the jobs, living standards and working conditions of all workers.

This requires taking the conduct of the strike out of the hands of the pro-company union by establishing a rank-and-file strike committee, independent of the BCTGM, to establish lines of communication and joint action by workers across Kellogg’s global empire.

No comments:

Post a Comment