JAPAN

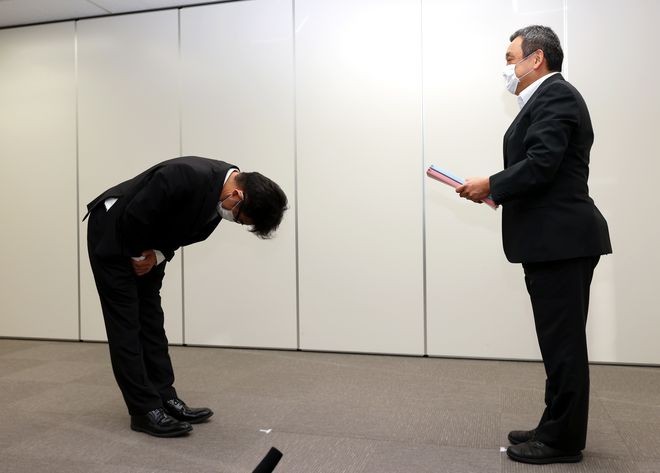

Atmosphere that stifles opinions behind corporate scandals

THE ASAHI SHIMBUN

January 14, 2022

Three recent scandals that rocked Japan Inc. shared a common background element: a corporate atmosphere that made it nearly impossible for employees to express their opinions to their bosses.

The inspection reports on the scandals showed management was not interested in workers’ views and lacked awareness of in-house issues, while lower-level employees were mainly concerned with doing what they thought their managers wanted.

In June, it came to light that Mitsubishi Electric Corp. had falsified quality control data for equipment supplied to railway companies for more than 30 years.

The company’s investigation committee reported accounts of employees who knew about the falsifications but felt they could not raise objections.

“It was not that the corporation itself was untrustworthy, but rather that I did not have any trust in senior officials at my work,” one worker who decided not to blow the whistle told the inquiry panel. “They were only concentrated on glossing over problems and protecting themselves in the upper ranks.”

Another individual noted Mitsubishi Electric’s countermeasures against past problems were worth next to nothing.

“Aside from the falsified quality issue, labor problems had repeatedly erupted,” the employee said. “Although the company seemingly took steps each time such an issue arose, they brought no changes to our working conditions.”

When more than 4,000 ATMs of Mizuho Bank broke down in February 2021, the financial institute failed to quickly relay information to its customers and management.

Koji Fujiwara, president of Mizuho Bank, reportedly learned of the ATM failure through an online news article.

A company inspection report, which included the results of a questionnaire survey, said one cause of the problem was workers’ tendency to pay attention only to the feelings of higher officials.

“We do not put customers first and give top priority to efficiency and the management’s intentions,” a questionnaire respondent said. “Our less-profitable retail department faces strong pressure for cost reduction in particular, leading to slashed funds to maintain its online system.”

Another worker explained that opinions of lower-level employees are not conveyed to the headquarters of Mizuho Bank, and that many decisions are based only on the predicted intentions of management.

“The inward-oriented stance and management’s reliance on precedents without taking risks are problematic,” the employee said. “We were ordered not to explain details to customers at the time of the ATM accident.”

NUCLEAR SAFETY IN DANGER

Tokyo Electric Power Co. is moving to restart the Kashiwazaki-Kariwa nuclear power plant in Niigata Prefecture.

But an employee was found to have used a different individual’s ID card to enter the station’s central control room in 2020, underscoring a continued deficiency in security measures to stop intruders.

A report released in September by an independent committee highlights the frustrations of the power company’s staff members.

TEPCO workers were asked through a questionnaire whether “there was the corporate climate where one cannot give their frank opinions.” Around 27 percent of those working at the Kashiwazaki-Kariwa plant fully or somewhat agreed with that statement.

“As an atomic power operator, the company lacks awareness of nuclear security,” one questionnaire respondent wrote. “The organization attempts to avoid responsibility and leaves everything to individuals. It does not bear any liability as an organization.”

TEPCO, operator of the crippled Fukushima No. 1 nuclear power plant, had previously been involved in covering up trouble and fabricating data at its nuclear power facilities.

The company’s less-open atmosphere has been criticized on many occasions, but there appears to be no signs for improvement.

A respondent in the questionnaire said TEPCO employees have a “deep-rooted excessive tendency” to behave in line with their supervisors’ intentions, and the trend is “especially prominent” among those in managerial positions at TEPCO’s headquarters.

Another TEPCO employee said that senior officials’ “high-handed” stance makes it difficult to create an atmosphere in which workers can express their views.

“The executives are a piece of junk and do not figure out the actual situation at the facilities,” the employee wrote in the questionnaire. “Even if we submit opinions and proposals, they cannot understand them. I therefore feel that doing so is meaningless and useless.”

LONG WAY TO GO

All three companies said they are stepping up efforts to prevent a recurrence, but their in-house inspections indicate they face uphill battles.

“I have never felt it has become easier for us to speak our opinions,” said a Mitsubishi Electric employee. “The personnel causing the problems have not taken responsibility, but measures are being developed to prevent a recurrence. The organization’s nature will never change that way.”

Hideaki Kubori, a lawyer well-versed in corporate governance, said an effective whistle-blowing system is needed to break corporate traditions.

“If whistle-blowers are free from blame and given promotions, information on possible problems could be collected,” Kubori said. “The phrase of ‘reforming the corporation climate’ is often used as a slogan, but taking concrete steps, such as installing a mechanism to protect whistle-blowers, is indispensable to fulfilling that goal.”

(This article was written by Satoshi Shinden and Hisashi Naito.)

No comments:

Post a Comment