As burn-out mounts, a history book reminds we must improve conditions as we seek new recruits.

Crawford Kilian 25 Feb 2022TheTyee.ca

Crawford Kilian is a contributing editor of The Tyee.

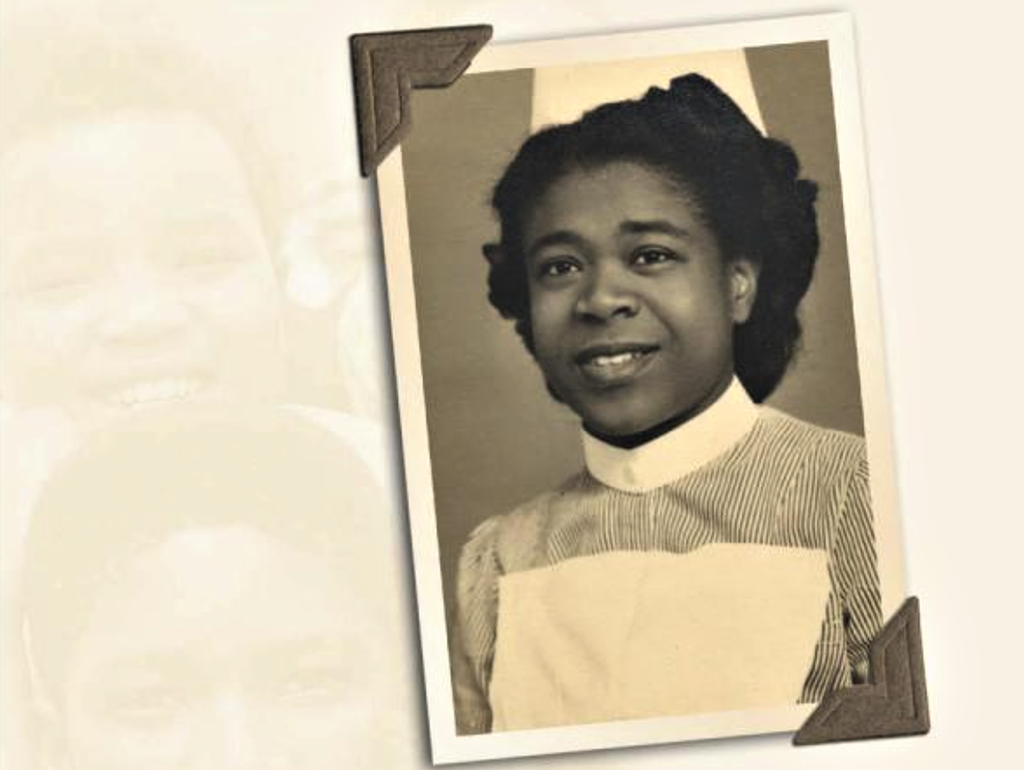

A detail from the cover of Moving Beyond Borders shows one of many Black recruits who, beginning in the 1940s, broke the colour barrier in Canadian nursing.

Moving Beyond Borders: A History of Black Canadian and Caribbean Women in the Diaspora

By Karen Flynn

University of Toronto Press (2011)

Canadian health care is two years into a pandemic, and its troubles are only just beginning. This book points to a solution.

Doctors, nurses, technologists and other staff are exhausted. Many are quitting, or taking early retirement, or dying. Those who remain are overworked and taking abuse and violence from some of the people they’re trying to save.

And whatever the politicians say about “living” with COVID, health-care workers will still have to care for COVID patients who die with it, as well as all the other routine duties involved in looking after an aging Canada.

The BC NDP’s new budget is a case in point. The Hospital Employees’ Union responded to it with a warning from HEU secretary-business manager Meena Brisard: “The budget includes 6.6 per cent increase to core health spending in 2022–23 but holds planned spending increases in future years below the levels needed to support health-care delivery in the face of a growing and aging population, and inflation.

“We strongly support the premier’s efforts to secure a higher level of support from the federal government for health-care spending. But we also need to plan today for the health-care system we need in the years ahead.”

The BC Nurses’ Union, meanwhile, has surveyed its members and found them alarmingly ready to leave the profession. Two out of five nurses in their 20s said they were likely to leave after the pandemic, and over a third of those in their 30s.

As for the future, the BCNU said: “As the pandemic wears on, we are asking that a plan be developed that addresses the crippling staffing shortage, unrealistic working conditions, and recruitment and retention of nurses in every part of this province.

“The results show us that nurses are more willing to stay in the profession if they are better protected from violence in the workplace, if they have unfettered access to PPE and have enough nursing colleagues to meet the demands of the health-care system.”

Even if today’s nurses stay in their jobs, the profession is still understaffed. The B.C. government is adding 602 new nursing seats to programs that now have about 2,000, but even that is unlikely to meet growing future needs — especially if attrition continues.

We’ve been here before, scrambling for more people to staff a health-care system trying to meet sharply increased demand. We will likely do it the same way now that we did in the decades after the Second World War: by recruiting overseas. But this time we’ll have to do it while also transforming the whole system.

Karen Flynn, an associate professor at the University of Illinois, published the remarkable book Moving Beyond Borders: A History of Black Canadian and Caribbean Women in the Diaspora in 2011. She interviewed 35 Black Caribbean and Canadian women who had entered nursing from the 1940s to the 1960s. Most had been recruited to work in Britain’s new National Health Service, and were trained in British hospitals. They eventually migrated to Canada, sometimes after a return to the Caribbean.

On its face, Dr. Flynn’s book might seem to be focused on Black medical history, offering a study of some of the first Black women to break into a hitherto white profession. But in 2022, it looks like a manual on how to save the whole health-care system. Her interviews go deep into the nurses’ childhoods and the mid-century cultures of Canada, Britain and the Caribbean. She learns how the nurses grew up with norms of gender and race and class, and how they dealt with both individual and systemic racism.

By showing us these women’s origins, and the system they contended with, Flynn offers guidelines for our own system, which still retains many of the weaknesses of the 1950s and ’60s. Black nurses learned how to work around those weaknesses, or even ignore them, while still delivering excellent care. We’ll have to look for similar traits in the health-care workers of the coming decades.

Recruited out of desperation

Capable though they were, Flynn’s young women were recruited out of desperation to staff a system that didn’t think much of them. Britain’s Caribbean colonies had long been impoverished and forgotten, but the new National Health System faced a critical shortage of skilled labour after the war. Canadian Black women were equally impoverished, and perhaps more aware of this inequity than their counterparts in the Caribbean.

Once in Britain, the young women encountered racism at every level, from patients who didn’t want to be touched by Black hands to matrons who referred to them using slurs.

They found themselves on the bottom of a hierarchy, with white male doctors at the top and white female nurses and matrons just below them. All nurses were expected to behave like proper white middle-class girls; that put the Black students at an instant disadvantage. One 1960s student grew a big Afro, and kept her nurse’s cap so far back on it that her matron could barely see it — a daring act of resistance.

Another act of resistance was to refute their white instructors’ biases by becoming the best students in class, and then the best nurses in the hospital. But it took infinite patience to endure the casual bigotries of their teachers and colleagues.

‘De-skilling’ professionals

Black nurses who migrated to Canada carried the prestige of their British training and experience, but found themselves in a very different culture: jobs they did routinely in Britain were now the preserve of doctors only; the nurses themselves were “de-skilled” with tasks that should have belonged to nurses’ aides and orderlies. Some moved on to better careers in U.S. cities like Detroit.

No doubt much has changed in Canadian health care since the 1960s, but racism remains ingrained against Indigenous people in the system. And after all these years, it’s still a persistent problem for Black Canadian nurses.

The Registered Nurses’ Association of Ontario recently published the report of its Black Nurses Task Force, saying: “RNAO recognizes that racism is a public health crisis that contributes to health and socioeconomic disparities and must be urgently dismantled. RNAO launched its Black Nurses Task Force in June 2020 to acknowledge, address and tackle the anti-Black racism deeply ingrained in the nursing profession.”

Health-care professionals should read the report, as well as Dr. Flynn’s book, while taking detailed notes. It’s no longer enough to recruit people of colour on the principle that “any warm body will do.” Recruitment will require understanding the cultural backgrounds of potential health-care workers, and assessing their ability to work within a system while also dismantling its racist, classist and sexist components.

Recruit the best

Regardless of race, class or gender, every health-care worker should be scouted like a promising high school hockey player, recruited into top schools and rigorously trained. Hospitals and clinics should compete for such graduates, offering excellent pay, working conditions and support.

Many will be Indigenous, Black or from overseas; immigrant health-care workers should be welcomed like foreign investors, not like unqualified imposters. Varied backgrounds, training and skills should be judged as advantages. It should be cheap and easy for immigrants to train to meet local standards.

Nurses Are in Crisis, and Banging Pots Isn’t Going to Fix It READ MORE

Like the British in the 1940s, we may well need to attempt to draw from lower-income countries who already lack enough workers for their own needs. Rather than grab the best for ourselves, we could help fund their medical and nursing programs and train their teachers, on a scale that would enable such countries to export health-care workers, like the Philippines and Cuba. We could then recruit the graduates we need, while their classmates work in hospitals around the world.

Yes, it would be expensive. It would upset the status of the doctors and administrators now at the top of the hierarchy, and the cost would annoy taxpayers who think they’ll never get sick. Some people would still come out of hospital complaining about the food or the beds instead of marvelling that they’re still alive thanks to the care they got.

But however costly it may be to train and employ workers in our future health-care system, it will be vastly cheaper than burning them out and throwing them away. The pandemic has shown us that inequality — whether from racism, sexism or classism — is a health threat at least as serious as COVID-19 itself. A society that cares about its caregivers will be far happier and healthier than one caring only for those at the top.

Moving Beyond Borders: A History of Black Canadian and Caribbean Women in the Diaspora

By Karen Flynn

University of Toronto Press (2011)

Canadian health care is two years into a pandemic, and its troubles are only just beginning. This book points to a solution.

Doctors, nurses, technologists and other staff are exhausted. Many are quitting, or taking early retirement, or dying. Those who remain are overworked and taking abuse and violence from some of the people they’re trying to save.

And whatever the politicians say about “living” with COVID, health-care workers will still have to care for COVID patients who die with it, as well as all the other routine duties involved in looking after an aging Canada.

The BC NDP’s new budget is a case in point. The Hospital Employees’ Union responded to it with a warning from HEU secretary-business manager Meena Brisard: “The budget includes 6.6 per cent increase to core health spending in 2022–23 but holds planned spending increases in future years below the levels needed to support health-care delivery in the face of a growing and aging population, and inflation.

“We strongly support the premier’s efforts to secure a higher level of support from the federal government for health-care spending. But we also need to plan today for the health-care system we need in the years ahead.”

The BC Nurses’ Union, meanwhile, has surveyed its members and found them alarmingly ready to leave the profession. Two out of five nurses in their 20s said they were likely to leave after the pandemic, and over a third of those in their 30s.

As for the future, the BCNU said: “As the pandemic wears on, we are asking that a plan be developed that addresses the crippling staffing shortage, unrealistic working conditions, and recruitment and retention of nurses in every part of this province.

“The results show us that nurses are more willing to stay in the profession if they are better protected from violence in the workplace, if they have unfettered access to PPE and have enough nursing colleagues to meet the demands of the health-care system.”

Even if today’s nurses stay in their jobs, the profession is still understaffed. The B.C. government is adding 602 new nursing seats to programs that now have about 2,000, but even that is unlikely to meet growing future needs — especially if attrition continues.

We’ve been here before, scrambling for more people to staff a health-care system trying to meet sharply increased demand. We will likely do it the same way now that we did in the decades after the Second World War: by recruiting overseas. But this time we’ll have to do it while also transforming the whole system.

Karen Flynn, an associate professor at the University of Illinois, published the remarkable book Moving Beyond Borders: A History of Black Canadian and Caribbean Women in the Diaspora in 2011. She interviewed 35 Black Caribbean and Canadian women who had entered nursing from the 1940s to the 1960s. Most had been recruited to work in Britain’s new National Health Service, and were trained in British hospitals. They eventually migrated to Canada, sometimes after a return to the Caribbean.

On its face, Dr. Flynn’s book might seem to be focused on Black medical history, offering a study of some of the first Black women to break into a hitherto white profession. But in 2022, it looks like a manual on how to save the whole health-care system. Her interviews go deep into the nurses’ childhoods and the mid-century cultures of Canada, Britain and the Caribbean. She learns how the nurses grew up with norms of gender and race and class, and how they dealt with both individual and systemic racism.

By showing us these women’s origins, and the system they contended with, Flynn offers guidelines for our own system, which still retains many of the weaknesses of the 1950s and ’60s. Black nurses learned how to work around those weaknesses, or even ignore them, while still delivering excellent care. We’ll have to look for similar traits in the health-care workers of the coming decades.

Recruited out of desperation

Capable though they were, Flynn’s young women were recruited out of desperation to staff a system that didn’t think much of them. Britain’s Caribbean colonies had long been impoverished and forgotten, but the new National Health System faced a critical shortage of skilled labour after the war. Canadian Black women were equally impoverished, and perhaps more aware of this inequity than their counterparts in the Caribbean.

Once in Britain, the young women encountered racism at every level, from patients who didn’t want to be touched by Black hands to matrons who referred to them using slurs.

They found themselves on the bottom of a hierarchy, with white male doctors at the top and white female nurses and matrons just below them. All nurses were expected to behave like proper white middle-class girls; that put the Black students at an instant disadvantage. One 1960s student grew a big Afro, and kept her nurse’s cap so far back on it that her matron could barely see it — a daring act of resistance.

Another act of resistance was to refute their white instructors’ biases by becoming the best students in class, and then the best nurses in the hospital. But it took infinite patience to endure the casual bigotries of their teachers and colleagues.

‘De-skilling’ professionals

Black nurses who migrated to Canada carried the prestige of their British training and experience, but found themselves in a very different culture: jobs they did routinely in Britain were now the preserve of doctors only; the nurses themselves were “de-skilled” with tasks that should have belonged to nurses’ aides and orderlies. Some moved on to better careers in U.S. cities like Detroit.

No doubt much has changed in Canadian health care since the 1960s, but racism remains ingrained against Indigenous people in the system. And after all these years, it’s still a persistent problem for Black Canadian nurses.

The Registered Nurses’ Association of Ontario recently published the report of its Black Nurses Task Force, saying: “RNAO recognizes that racism is a public health crisis that contributes to health and socioeconomic disparities and must be urgently dismantled. RNAO launched its Black Nurses Task Force in June 2020 to acknowledge, address and tackle the anti-Black racism deeply ingrained in the nursing profession.”

Health-care professionals should read the report, as well as Dr. Flynn’s book, while taking detailed notes. It’s no longer enough to recruit people of colour on the principle that “any warm body will do.” Recruitment will require understanding the cultural backgrounds of potential health-care workers, and assessing their ability to work within a system while also dismantling its racist, classist and sexist components.

Recruit the best

Regardless of race, class or gender, every health-care worker should be scouted like a promising high school hockey player, recruited into top schools and rigorously trained. Hospitals and clinics should compete for such graduates, offering excellent pay, working conditions and support.

Many will be Indigenous, Black or from overseas; immigrant health-care workers should be welcomed like foreign investors, not like unqualified imposters. Varied backgrounds, training and skills should be judged as advantages. It should be cheap and easy for immigrants to train to meet local standards.

Nurses Are in Crisis, and Banging Pots Isn’t Going to Fix It READ MORE

Like the British in the 1940s, we may well need to attempt to draw from lower-income countries who already lack enough workers for their own needs. Rather than grab the best for ourselves, we could help fund their medical and nursing programs and train their teachers, on a scale that would enable such countries to export health-care workers, like the Philippines and Cuba. We could then recruit the graduates we need, while their classmates work in hospitals around the world.

Yes, it would be expensive. It would upset the status of the doctors and administrators now at the top of the hierarchy, and the cost would annoy taxpayers who think they’ll never get sick. Some people would still come out of hospital complaining about the food or the beds instead of marvelling that they’re still alive thanks to the care they got.

But however costly it may be to train and employ workers in our future health-care system, it will be vastly cheaper than burning them out and throwing them away. The pandemic has shown us that inequality — whether from racism, sexism or classism — is a health threat at least as serious as COVID-19 itself. A society that cares about its caregivers will be far happier and healthier than one caring only for those at the top.

No comments:

Post a Comment