COP15

- '30 by 30' -

The cornerstone of the agreement is the so-called 30 by 30 goal -- a pledge to protect 30 percent of the world's land and seas by 2030.

Currently, only about 17 percent of land and seven percent of oceans are protected.

And some experts say 30 percent is a low aim, insisting that protecting 50 percent would be better.

So far, more than 100 countries have publicly pledged support for the 30 by 30 target, and observers say it has received broad support among negotiators.

"For COP15 to be a success, we need to hold the line on our existing level of ambition," Alfred DeGemmis, of the Wildlife Conservation Society, told AFP.

Brian O'Donnell of the Campaign for Nature added it was key that the text applies to oceans, as well as land, which had been in doubt.

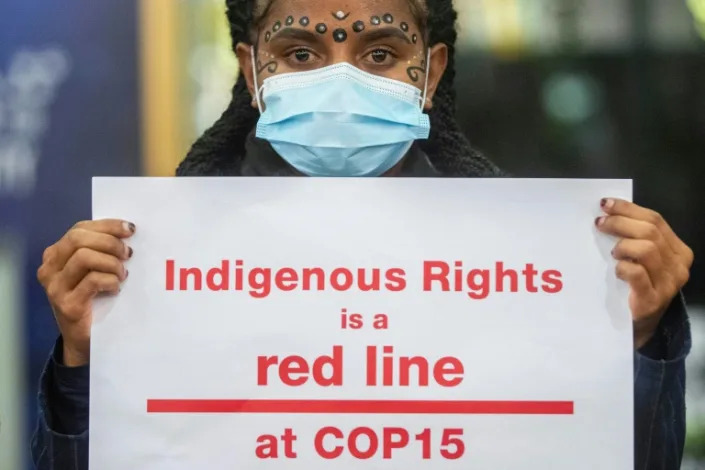

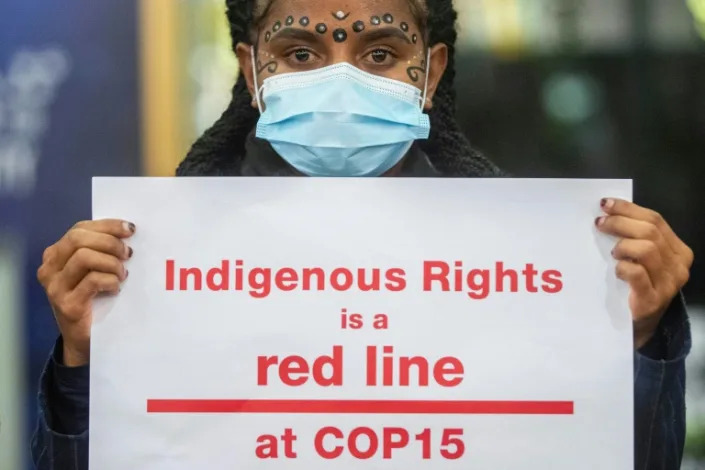

- Indigenous rights -

The question of Indigenous rights will be crucial.

About 80 percent of the Earth's remaining biodiverse land is currently managed by Indigenous people, and it's broadly recognized that biodiversity is better respected on Indigenous territory.

Many activists want to make sure their rights are not trampled in the name of conservation -- previous efforts to safeguard land have seen Indigenous communities marginalized or displaced in what has been dubbed "green colonialism."

Advocates say therefore these rights have to be adequately addressed throughout the text, including within the 30 by 30 pledge, so that Indigenous people are not subject to mass evictions.

Failure on this front would be a "complete red line for us," said O'Donnell.

"We are the ones doing the work. We protect biodiversity. You won't replace us. We won't let you," said Valentin Engobo, leader of the Lokolama community in the Congo Basin, which protects the world's largest tropical peatland.

"You can be our partners, if you want. But you cannot push us out."

- Loopholes matter -

As a general principle, it is vital that the targets envisioned in the text aren't significantly weakened through loopholes that will weaken actual implementation, said Georgina Chandler of the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds.

For example, during some plenary sessions, some ministers had suggested stripping out language about numerical targets for ecosystem restoration.

"Keeping those measurable elements...and making sure that they are ambitious, is really, really important," said Chandler.

Other things she'll be watching include whether there will be a commitment to halve pesticide use, and whether businesses will be mandated to assess and report on the biodiversity impacts.

- Finance -

As ever, money remains a difficult question.

Developing countries say developed nations grew rich by exploiting their resources and the South should be paid to preserve its ecosystems.

Several countries have announced new commitments either at the COP or recently, with Europe emerging as a key leader. The European Union has committed seven billion euros ($7.4 billion) for the period until 2027, double its prior pledge.

But Brazil has led a charge by developing countries for far more, proposing flows of $100 billion annually, compared to the roughly $10 billion at present.

Developing countries are also seeking a new funding mechanism, as a signal of the rich world's commitment to this goal.

Whether international aid is delivered via a new fund, an existing mechanism called the Global Environment Facility (GEF), or a halfway solution involving a new "trust fund" within the GEF is still up for debate.

bur-ia/rlp/md

Activists, experts say there's still hope for a breakthrough at COP15What campaigners want to see in UN nature deal

Issam AHMED, AFP

Sat, December 17, 2022

As high-stakes UN biodiversity talks in Montreal draw to a close, delegates will be presented Sunday with a draft deal to safeguard the planet's ecosystems and species by 2030.

Will it amount to the "peace pact with nature" that UN chief Antonio Guterres said the world desperately needs? Campaigners say the devil lies in the details. Here's what they're looking out for:

Issam AHMED, AFP

Sat, December 17, 2022

As high-stakes UN biodiversity talks in Montreal draw to a close, delegates will be presented Sunday with a draft deal to safeguard the planet's ecosystems and species by 2030.

Will it amount to the "peace pact with nature" that UN chief Antonio Guterres said the world desperately needs? Campaigners say the devil lies in the details. Here's what they're looking out for:

- '30 by 30' -

The cornerstone of the agreement is the so-called 30 by 30 goal -- a pledge to protect 30 percent of the world's land and seas by 2030.

Currently, only about 17 percent of land and seven percent of oceans are protected.

And some experts say 30 percent is a low aim, insisting that protecting 50 percent would be better.

So far, more than 100 countries have publicly pledged support for the 30 by 30 target, and observers say it has received broad support among negotiators.

"For COP15 to be a success, we need to hold the line on our existing level of ambition," Alfred DeGemmis, of the Wildlife Conservation Society, told AFP.

Brian O'Donnell of the Campaign for Nature added it was key that the text applies to oceans, as well as land, which had been in doubt.

- Indigenous rights -

The question of Indigenous rights will be crucial.

About 80 percent of the Earth's remaining biodiverse land is currently managed by Indigenous people, and it's broadly recognized that biodiversity is better respected on Indigenous territory.

Many activists want to make sure their rights are not trampled in the name of conservation -- previous efforts to safeguard land have seen Indigenous communities marginalized or displaced in what has been dubbed "green colonialism."

Advocates say therefore these rights have to be adequately addressed throughout the text, including within the 30 by 30 pledge, so that Indigenous people are not subject to mass evictions.

Failure on this front would be a "complete red line for us," said O'Donnell.

"We are the ones doing the work. We protect biodiversity. You won't replace us. We won't let you," said Valentin Engobo, leader of the Lokolama community in the Congo Basin, which protects the world's largest tropical peatland.

"You can be our partners, if you want. But you cannot push us out."

- Loopholes matter -

As a general principle, it is vital that the targets envisioned in the text aren't significantly weakened through loopholes that will weaken actual implementation, said Georgina Chandler of the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds.

For example, during some plenary sessions, some ministers had suggested stripping out language about numerical targets for ecosystem restoration.

"Keeping those measurable elements...and making sure that they are ambitious, is really, really important," said Chandler.

Other things she'll be watching include whether there will be a commitment to halve pesticide use, and whether businesses will be mandated to assess and report on the biodiversity impacts.

- Finance -

As ever, money remains a difficult question.

Developing countries say developed nations grew rich by exploiting their resources and the South should be paid to preserve its ecosystems.

Several countries have announced new commitments either at the COP or recently, with Europe emerging as a key leader. The European Union has committed seven billion euros ($7.4 billion) for the period until 2027, double its prior pledge.

But Brazil has led a charge by developing countries for far more, proposing flows of $100 billion annually, compared to the roughly $10 billion at present.

Developing countries are also seeking a new funding mechanism, as a signal of the rich world's commitment to this goal.

Whether international aid is delivered via a new fund, an existing mechanism called the Global Environment Facility (GEF), or a halfway solution involving a new "trust fund" within the GEF is still up for debate.

bur-ia/rlp/md

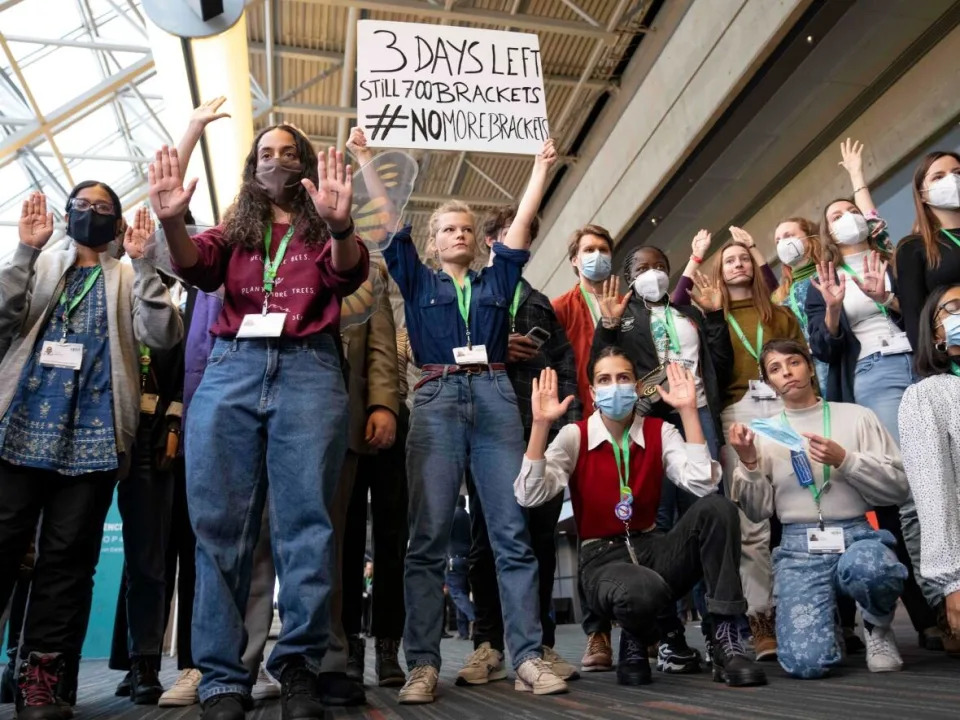

Sat, December 17, 2022

Members of the Global Youth Biodiversity Network demonstrate in the halls of the convention centre at the COP15 UN conference on biodiversity in Montreal on Friday, December 16, 2022.

(Paul Chiasson/The Canadian Press - image credit)

Between claims that negotiations are moving far too slowly and a mid-week walkout by a group of developing nations, there are ample reasons to worry that the world won't come to an agreement to protect biodiversity at COP15 in Montreal.

But the scientists, activists and political leaders attending the international conference this week all said they continue to have hope for the talks — and for the planet.

Kenyan scientist David Obura has seen firsthand how changing ocean temperatures bleached previously pristine coral reefs in the Pacific Ocean. He also saw those reefs rebound after Pacific Islanders made them a protected area.

"Biodiversity loss is just a complicated way to say that the nature around us is declining," he said.

Obura told CBC Radio's The House that when it comes to some of the targets the conference aims to achieve, negotiators have to take into account the particular circumstances countries face.

Take the call for a "30 by 30" target of protecting 30 per cent of the world's land and marine areas by 2030. Obura said that's intended as a global target — but it can't mean that all individual countries must protect 30 per cent of their territory.

Africa has a growing population and much of the continent is arid and not very productive agriculturally, he said. That makes it very hard for many African nations to turn large swaths of territory into protected areas, he added.

Between claims that negotiations are moving far too slowly and a mid-week walkout by a group of developing nations, there are ample reasons to worry that the world won't come to an agreement to protect biodiversity at COP15 in Montreal.

But the scientists, activists and political leaders attending the international conference this week all said they continue to have hope for the talks — and for the planet.

Kenyan scientist David Obura has seen firsthand how changing ocean temperatures bleached previously pristine coral reefs in the Pacific Ocean. He also saw those reefs rebound after Pacific Islanders made them a protected area.

"Biodiversity loss is just a complicated way to say that the nature around us is declining," he said.

Obura told CBC Radio's The House that when it comes to some of the targets the conference aims to achieve, negotiators have to take into account the particular circumstances countries face.

Take the call for a "30 by 30" target of protecting 30 per cent of the world's land and marine areas by 2030. Obura said that's intended as a global target — but it can't mean that all individual countries must protect 30 per cent of their territory.

Africa has a growing population and much of the continent is arid and not very productive agriculturally, he said. That makes it very hard for many African nations to turn large swaths of territory into protected areas, he added.

Paul Chiasson/The Canadian Press

At the same time, he said, wealthy nations have made a lot of money from extracting resources from Asia and Africa — commercial activity that has played a large role in biodiversity decline.

"If you want us now to be involved in protecting what's remaining, which means giving up certain things on our side, show us the money. It's as simple as that," he said.

Ecuadorian activist Alicia Guzmán León points out that her country leads the chronic malnutrition index. The Amazon program director for Stand.earth said it's not realistic for wealthy countries to demand that countries like hers prioritize creating and paying for new protected areas.

In the early hours of Wednesday, a group of developing nations — frustrated over how the discussions were progressing — walked out of the talks.

Still, both Guzmán León and Obura said they remain hopeful.

"Each year that we have, we can turn towards a better trajectory," said Obura. "We just should have done it 10 or 20 years ago or 30 years ago.

"I'm not an optimist or pessimist, just a realist. I have a kid. So, you know, we have to try and make it work."

Walkout prompts wealthy countries to put up more money

Canadian Tim Hodges is a veteran of these major gatherings. He co-chaired the last big negotiation under the Convention on Biological Diversity.

"It's really about developed countries versus developing countries," said Hodges, describing the major tensions underlying the current talks.

"While we're talking about biodiversity, really the dynamic below the surface is about power, is about influence, it's about money and it's about benefits."

He cautioned that the mid-week walkout shouldn't be seen as a sign talks will fail.

The walkout led wealthier countries to put more money on the table, U.K.'s Minister for International Environment and Climate Zac Goldsmith told CBC's The Current.

Goldsmith described it as "almost a doubling of previous commitments."

Canada, which already had announced $350 million to support biodiversity projects in developing countries at the start of the conference, announced an additional $255 million on Friday.

Pledging additional funds can be a difficult choice for some wealthier countries, said Jochen Flasbarth, the state secretary for Germany's Ministry of Economic Cooperation and Development.

While states from around the world are finally recognizing the need for action on biodiversity preservation, this year's COP comes at a moment when rich countries are struggling with a rash of crises that have drawn resources from their reserves.

"In the so-called donor countries, budgets are highly under pressure. We are in an extremely difficult world situation, with multiple crises after COVID [and] now the Russian war against Ukraine. All of this affects countries, and all of this needs the solidarity of the north," he said.

"So it's not a fortunate situation to solve this, but still we have to do it."

Flasbarth also stressed that money is only part of the solution.

"I think we should also look at what do we want to achieve in the substance. For example, the way we are doing agriculture and forestry and fisheries around the world is not sustainable and it's affecting biodiversity," he said.

"Yes, we need some money to transform these sectors into more sustainable and biodiversity-friendly practices, but it's also about what countries can do at home to regulate this. It's not all about money."

Hodges said that what matters isn't simply getting to a deal, but getting to a deal that works.

"The question for me is, do we actually get an agreement that's full of substance and real commitment that makes countries and people behave differently and get a different record?" he said. "Or were you just going to make empty promises and not meet those commitments?"

No comments:

Post a Comment