How much profit are UK supermarkets making amid the cost crisis?

Henry Saker-Clark, PA Deputy Business Editor

Tue, 27 June 2023

Bosses at UK supermarkets have denied they are profiteering from customers who have witnessed soaring increases in their food bills.

Executives from Tesco, Sainsbury’s, Asda and Morrisons all defended their actions to MPs on Tuesday amid scrutiny over behaviour by firms in the sector.

The latest official figures showed that food inflation eased slightly last month but remained at a stubbornly high 18.4%.

The UK’s competition regulator is currently investigating how price increases and decreases in food and fuel have been passed onto consumers.

Here the PA news agency highlights how much profit the biggest supermarket chains have made and how it compares to previous years:

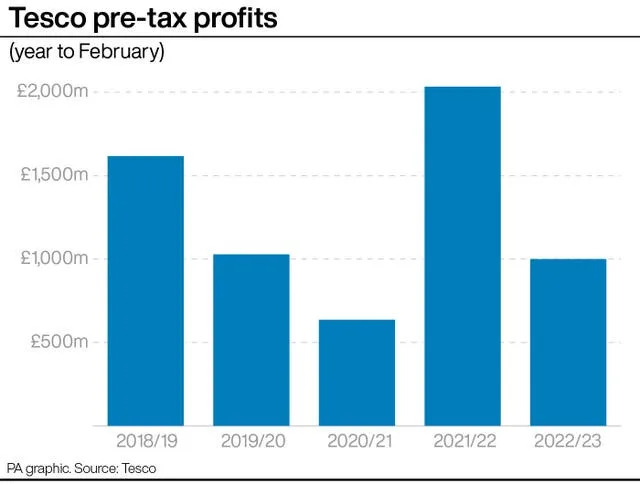

Tesco

The UK’s biggest supermarket chain saw its profits cut by more than half in its latest financial year.

Tesco – which employs more than 300,000 people – saw its profits drop to £1 billion in the year to February 2023, from £2.03 billion in the previous year.

Tesco pre-tax profits for the past five financial years (PA Graphics)

It came despite a 5.3% increase in its sales, excluding VAT and fuel, over the year.

The grocery giant blamed lower profits for the year on lower sales volumes, investment in the business and steep cost rises.

Tesco saw its profits slide following the impact of the Covid-19 as it swallowed higher costs related to the pandemic and opted to hand business rates tax relief back to the Government.

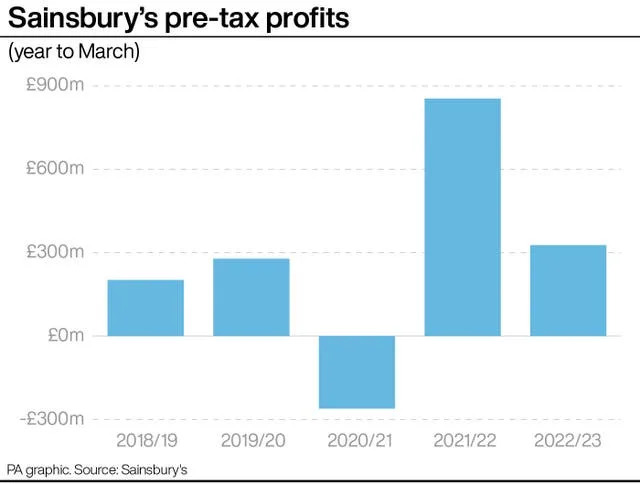

Sainsbury’s

The second largest supermarket group, which also owns Argos, reported its own drop in profits last year.

In April, Sainsbury’s revealed that statutory profits tumbled by more than half to £327 million, while underlying profits were also 5% lower year-on-year.

Sainsbury’s pre-tax profits for the past five years (PA Graphics)

It said this was partly driven by a £560 million investment into lower pricing to keep shoppers coming into its stores.

On Tuesday, the retailer’s food commercial director Rhian Bartlett that it has increased the price of products on shelves “behind input cost inflation”.

Asda

Asda followed the pattern seen by most of its rivals of reported a fall in profits.

The privately-owned business, which was bought by the billionaire Issa brothers and private equity backers TDR Capital in 2021, recorded lower profits last year due to the impact of higher cost inflation.

The firm said adjusted earnings – Asda’s preferred measure of profitability – declined by almost a quarter to £886 million in 2022.

It also saw sales tip marginally higher for the year, as it was boosted by price cuts later in the year to attract more shoppers.

Morrisons

Fellow private equity-owned supermarket chain Morrisons also recorded a decline in earnings for the past financial year.

David Potts, CEO of Morrisons, appearing before the Business and Trade Committee (House of Commons/UK Parliament/PA)

The group, which was bought by private equity giant Clayton, Dubilier & Rice (CD&R) in 2021, revealed that adjusted earnings fell by 15% to £828 million over the year to October 30, from £975 million in the previous year.

On Tuesday, Morrisons chief executive David Potts denied claims that it was profiteering from price inflation and stressed that it would be quick to pass cost reductions on to its customers.

Aldi/Lidl

Numerous UK supermarket chains have said their profits have been lower as they have chosen to direct funds into keeping prices lower, at the expense of profitability.

This largely taken place in an effort to stop customers from fleeing to German discount rivals Aldi and Lidl, who have taken more market share over the past year as shoppers have looked to reduce the cost of their weekly shops.

Aldi has yet to reveal its profit data for last year, with its most recent figures showing that pre-tax profits slid to £35.7 million in 2021, from £264.8 million in 2020, blaming a jump in costs.

Similarly, Lidl has not yet revealed profits for the past year but recorded a pre-tax profit of £41.4 million for the year to February 2022.

This represented a 319% increase in profits compared with the previous year after cost reductions across the business.

Supermarket bosses reject calls for price caps and deny ‘grotesque profiteering

Archie Mitchell

Tue, 27 June 2023

Consumers have faced punishing increases in the cost of food in recent months (PA Wire)

Supermarket bosses have rejected calls for price caps on products and denied claims of “grotesque profiteering” during a grilling by MPs.

Executives from four of Britain’s biggest grocers were quizzed over rising prices and whether they are using inflation as an excuse to boost their profits.

They were also asked about the potential for price caps on some foods to help protect shoppers from spiralling costs.

But bosses from Tesco, Sainsbury’s, Asda and Morrisons mounted a staunch defence of the sector, insisting it remains “fiercely competitive”.

The representatives said they had not passed on all the costs of supply chain inflation to their customers, absorbing some of the shock in a hit to their own profits.

It comes as supermarkets are under increasing pressure to hand down savings on wholesale items to consumers, who have faced punishing food-price inflation in recent months.

Tesco commercial director Gordon Gafa was asked about a suggestion made by the general secretary of the Unite union, Sharon Graham, that supermarkets are guilty of a “grotesque display of profiteering” – a claim he rejected.

And he claimed that Tesco, the UK’s largest grocer, is the “most competitive we have ever been”.

Mr Gafa told the business and trade committee: “Profits year on year for the group are down. We have sold more year on year and we have made less.”

Sainsbury’s food commercial director Rhian Bartlett said the supermarket has spent £560m to lower prices for customers. “In the most recent year we made lower profits, at £690m – input costs are not being fully passed through to our shelf prices,” she said.

Questioned on speculation about a price cap for certain food products, Ms Bartlett said: “This is fiercely competitive as a market.

“We’re generally considered one of the most competitive food markets in the world. I’m not sure what price caps would add to that process, other than bureaucracy.

“Where we’ve seen them applied in France and so on, it can have unintended consequences – of selling out and other prices moving up and down ... So I think this market self-regulates to a positive extent.”

On Wednesday, Jeremy Hunt will pile pressure on regulators to investigate whether firms are exploiting rampant inflation to bolster their profits.

The competition watchdog is already investigating the grocery sector amid “ongoing concerns about high prices” and is looking at whether increases are linked to “any failure in competition”.

Data from the BRC-NielsenIQ Shop Price Index suggests that retailers are beginning to pass on lower wholesale costs, with food inflation easing for a second month running as supermarkets cut the price of household staples.

The rate of food inflation decelerated to 14.6 per cent in June, a relatively significant drop from May’s 15.4 per cent and below the three-month average of 15.2 per cent. But costs remain high overall.

Fresh-food inflation saw a significant slowing from May’s 17.2 per cent to 15.7 per cent as shops dropped the prices of basics including milk, cheese and eggs.

The grocers were also challenged over petrol prices, with the suggestion that consumers did not feel the benefit of Rishi Sunak’s 5p fuel-duty cut last March when he was chancellor.

Morrisons boss David Potts said the supermarket passed on the cut “on the same day”, but said that customers may not have benefited because of “the volatility within the market”.

Tesco, Sainsbury’s and Asda all suggested that they would back a Northern Ireland-style system to allow customers to check fuel prices at every petrol station online.

Mr Potts said he would be happy to look at “anything that can benefit consumers”.

Archie Mitchell

Tue, 27 June 2023

Consumers have faced punishing increases in the cost of food in recent months (PA Wire)

Supermarket bosses have rejected calls for price caps on products and denied claims of “grotesque profiteering” during a grilling by MPs.

Executives from four of Britain’s biggest grocers were quizzed over rising prices and whether they are using inflation as an excuse to boost their profits.

They were also asked about the potential for price caps on some foods to help protect shoppers from spiralling costs.

But bosses from Tesco, Sainsbury’s, Asda and Morrisons mounted a staunch defence of the sector, insisting it remains “fiercely competitive”.

The representatives said they had not passed on all the costs of supply chain inflation to their customers, absorbing some of the shock in a hit to their own profits.

It comes as supermarkets are under increasing pressure to hand down savings on wholesale items to consumers, who have faced punishing food-price inflation in recent months.

Tesco commercial director Gordon Gafa was asked about a suggestion made by the general secretary of the Unite union, Sharon Graham, that supermarkets are guilty of a “grotesque display of profiteering” – a claim he rejected.

And he claimed that Tesco, the UK’s largest grocer, is the “most competitive we have ever been”.

Mr Gafa told the business and trade committee: “Profits year on year for the group are down. We have sold more year on year and we have made less.”

Sainsbury’s food commercial director Rhian Bartlett said the supermarket has spent £560m to lower prices for customers. “In the most recent year we made lower profits, at £690m – input costs are not being fully passed through to our shelf prices,” she said.

Questioned on speculation about a price cap for certain food products, Ms Bartlett said: “This is fiercely competitive as a market.

“We’re generally considered one of the most competitive food markets in the world. I’m not sure what price caps would add to that process, other than bureaucracy.

“Where we’ve seen them applied in France and so on, it can have unintended consequences – of selling out and other prices moving up and down ... So I think this market self-regulates to a positive extent.”

On Wednesday, Jeremy Hunt will pile pressure on regulators to investigate whether firms are exploiting rampant inflation to bolster their profits.

The competition watchdog is already investigating the grocery sector amid “ongoing concerns about high prices” and is looking at whether increases are linked to “any failure in competition”.

Data from the BRC-NielsenIQ Shop Price Index suggests that retailers are beginning to pass on lower wholesale costs, with food inflation easing for a second month running as supermarkets cut the price of household staples.

The rate of food inflation decelerated to 14.6 per cent in June, a relatively significant drop from May’s 15.4 per cent and below the three-month average of 15.2 per cent. But costs remain high overall.

Fresh-food inflation saw a significant slowing from May’s 17.2 per cent to 15.7 per cent as shops dropped the prices of basics including milk, cheese and eggs.

The grocers were also challenged over petrol prices, with the suggestion that consumers did not feel the benefit of Rishi Sunak’s 5p fuel-duty cut last March when he was chancellor.

Morrisons boss David Potts said the supermarket passed on the cut “on the same day”, but said that customers may not have benefited because of “the volatility within the market”.

Tesco, Sainsbury’s and Asda all suggested that they would back a Northern Ireland-style system to allow customers to check fuel prices at every petrol station online.

Mr Potts said he would be happy to look at “anything that can benefit consumers”.

‘Greedflation’? The MPs missed the target when grilling the grocers

Nils Pratley

Tue, 27 June 2023

Photograph: Steve Parsons/PA

If you have given yourself less than 90 minutes to investigate one of the hottest business and political issues of the hour – the charge of “greedflation” as it applies to supermarkets – it is usually a good idea to stick to the subject. Sadly, this was not the approach adopted by MPs on the business and trade select committee on Tuesday.

The supposed grilling of a crew of supermarket representatives turned into a tour of multiple horizons, including boardroom pay and workers’ collective bargaining rights, which, though fascinating subjects, are only tangentially connected to the rising price of essential stuff.

The closest thing to a revelation was the admission by Morrisons’ David Potts, the only chief executive of the four-strong panel (why?), that there is “more profit at the retail end of fuel” these days. But that isn’t fresh news. It has been an open secret for at least a year that forecourt competition on petrol and diesel is less intense than it used to be (many point the finger at post-takeover changes at Asda). It is why the Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) has been taking a look – its final report is due next week.

But the next question will be whether the big supermarkets are less competitive on fuel because they are fighting harder on food via their various “Aldi price match” schemes and pledges. That will be their defence and it is worthy of consideration. If the transfer of competitive heat is real, many might regard the switch as legitimate and desirable during a cost of living crisis. Everyone must eat, but not everybody drives.

It would have been useful, then, to hear the supermarket representatives be pressed on the food v fuel margin trade-off in detail. It lies at the heart of this debate. The MPs, however, largely ignored such nuances.

In their absence, we got loose talk about “a cartel” and some apples-and-pears profit comparisons for Sainsbury’s, for instance, that ignored the role of exceptional charges in generating a supposedly enormous increase in returns from pre-pandemic levels. On a like-for-like underlying basis, the four-year increase was more like 15%. And, if food is the focus, one should also strip out the (probably increased) contribution from Argos. Such granular detail matters.

This committee session, then, would have been better timed after the CMA has opined on food and fuel prices. The competition regulator has the power to demand commercially sensitive price information of a sort that is never likely to be coughed up to MPs in a public forum. It is the only way to make definitive judgments about the true state of price tension in the market.

Until the CMA reports, the view here remains the same: yes, “greedinflation” is very likely to be contributing to inflation globally, as central banks and the International Monetary Fund belatedly suggest, but supermarkets are not the obvious candidates to put in the dock.

Tesco, the market leader, runs on profit margins of about 4% and Sainsbury’s does about 3%. That is in line with historical levels. Meanwhile, the lauded Aldi made a thin pre-tax profit of £36m on turnover of £13.6bn in its UK business in 2021, according to its last accounts at Companies House. The more obvious corporate culprits during the food inflation shock are the global agricultural giants who were unmentioned by the MPs.

Wait for the CMA. Its reports can’t fail to be more informative.

Nils Pratley

Tue, 27 June 2023

Photograph: Steve Parsons/PA

If you have given yourself less than 90 minutes to investigate one of the hottest business and political issues of the hour – the charge of “greedflation” as it applies to supermarkets – it is usually a good idea to stick to the subject. Sadly, this was not the approach adopted by MPs on the business and trade select committee on Tuesday.

The supposed grilling of a crew of supermarket representatives turned into a tour of multiple horizons, including boardroom pay and workers’ collective bargaining rights, which, though fascinating subjects, are only tangentially connected to the rising price of essential stuff.

The closest thing to a revelation was the admission by Morrisons’ David Potts, the only chief executive of the four-strong panel (why?), that there is “more profit at the retail end of fuel” these days. But that isn’t fresh news. It has been an open secret for at least a year that forecourt competition on petrol and diesel is less intense than it used to be (many point the finger at post-takeover changes at Asda). It is why the Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) has been taking a look – its final report is due next week.

But the next question will be whether the big supermarkets are less competitive on fuel because they are fighting harder on food via their various “Aldi price match” schemes and pledges. That will be their defence and it is worthy of consideration. If the transfer of competitive heat is real, many might regard the switch as legitimate and desirable during a cost of living crisis. Everyone must eat, but not everybody drives.

It would have been useful, then, to hear the supermarket representatives be pressed on the food v fuel margin trade-off in detail. It lies at the heart of this debate. The MPs, however, largely ignored such nuances.

In their absence, we got loose talk about “a cartel” and some apples-and-pears profit comparisons for Sainsbury’s, for instance, that ignored the role of exceptional charges in generating a supposedly enormous increase in returns from pre-pandemic levels. On a like-for-like underlying basis, the four-year increase was more like 15%. And, if food is the focus, one should also strip out the (probably increased) contribution from Argos. Such granular detail matters.

This committee session, then, would have been better timed after the CMA has opined on food and fuel prices. The competition regulator has the power to demand commercially sensitive price information of a sort that is never likely to be coughed up to MPs in a public forum. It is the only way to make definitive judgments about the true state of price tension in the market.

Until the CMA reports, the view here remains the same: yes, “greedinflation” is very likely to be contributing to inflation globally, as central banks and the International Monetary Fund belatedly suggest, but supermarkets are not the obvious candidates to put in the dock.

Tesco, the market leader, runs on profit margins of about 4% and Sainsbury’s does about 3%. That is in line with historical levels. Meanwhile, the lauded Aldi made a thin pre-tax profit of £36m on turnover of £13.6bn in its UK business in 2021, according to its last accounts at Companies House. The more obvious corporate culprits during the food inflation shock are the global agricultural giants who were unmentioned by the MPs.

Wait for the CMA. Its reports can’t fail to be more informative.

No comments:

Post a Comment