Big Tech lobbying is derailing the EU AI Act

BRAM VRANKEN 24th November 2023

Behind closed doors, the companies have fiercely lobbied the European Union to leave advanced artificial-intelligence systems unregulated.

Diaries cleared: the Google chief executive, Sundar Pichai (left), meeting the European commissioner for the internal market, Thierry Breton, last May—two other commissioners made themselves available to him that day

(Lukasz Kobus / European Commission)

As artificial-intelligence models are increasingly applied across society, it is becoming clear that these systems carry risks and can harm fundamental rights. Yet Big Tech—driving the AI revolution—is lobbying to stop regulation that could defend the public.

These social impacts are neither hypothetical nor confined to the future. For example, from the Netherlands and the United Kingdom to Australia, biased algorithms have falsely accused thousands of people of defrauding social-security benefits, with disastrous effects on their lives and livelihoods. In the Netherlands this affected tens of thousands, mostly from low-income households and/or a migrant background, driving victims into debt, homelessness and mental ill-health due to the extreme stress they experienced.

Structural biases

Over the last year, discussion has increasingly focused on the most advanced AI systems, known as ‘foundation models’, such as ChatGPT. These can be used for a wide range of purposes. The systems are often complex and behave in ways that can surprise even their own developers. Foundation models are trained on societal data and if the data carry structural biases—from racism to able-ism and more—these risk being baked into the systems.

Because of the scale and amounts of memory, data and hardware required, foundation models are primarily developed by the technology giants, such as Google and Microsoft. These near-monopolies in AI are reinforced through billion-dollar partnerships with ‘start-ups’, such as between Amazon and Anthropic or Microsoft and OpenAI. Tech giants have invested a massive $16.2 billion in OpenAI and Anthropic in the last year. As the AI Now Institute has written, ‘There is no AI without Big Tech.’

Alarmingly, these same firms have recently fired or trimmed down their ethics teams. In some cases these had called out some of the dangers of the systems they were developing.

Because of these risks, in the spring the European Parliament moved to impose certain obligations on companies developing foundation models—basically a duty of due diligence. Companies should show they had done everything they could to mitigate any risks to fundamental rights, check the quality of the data used to train these AI systems against any biases and lower their environmental impact: enormous amounts of electricity and water are used by the data centres.

Massive firepower

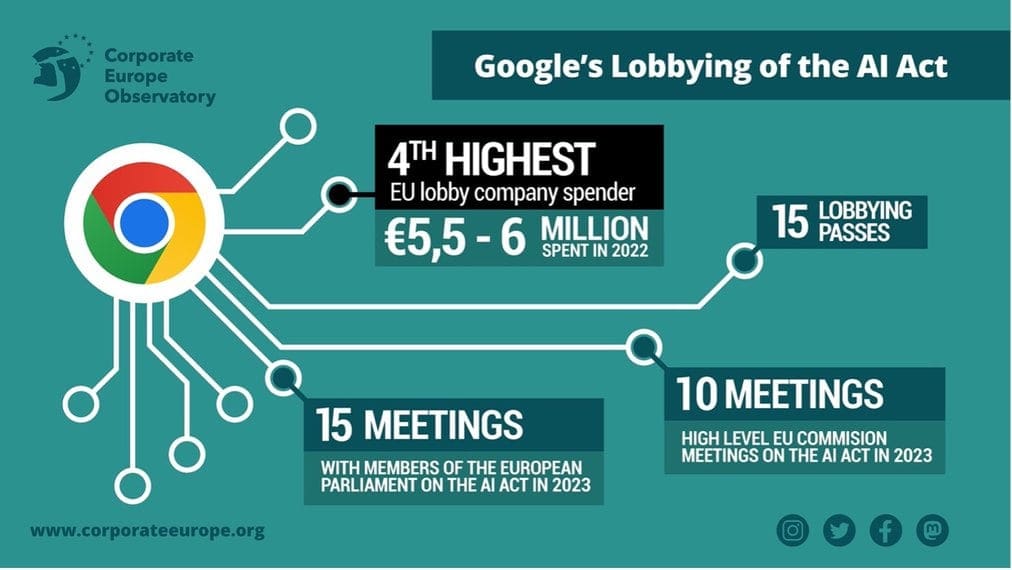

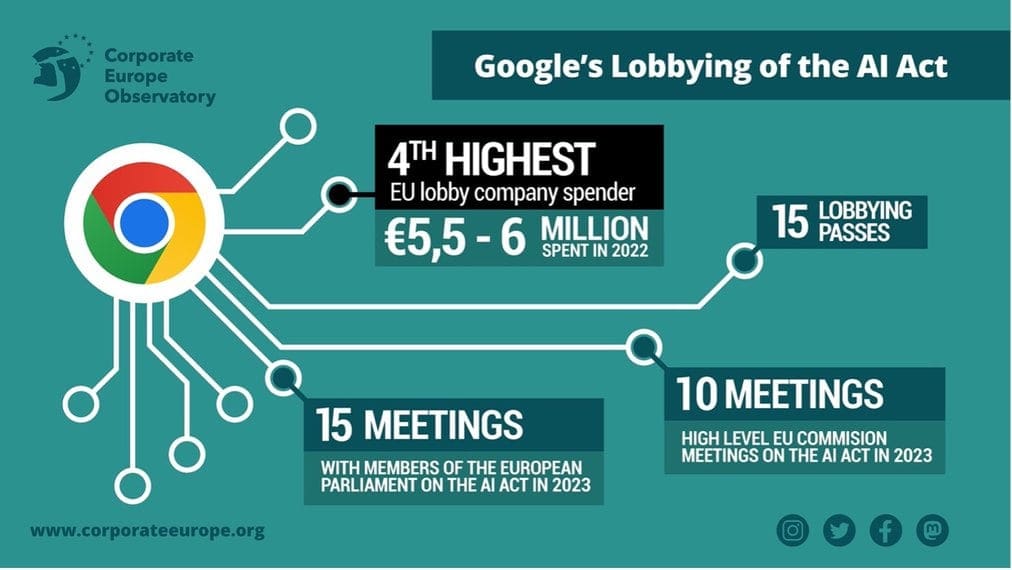

While publicly the tech companies have called on lawmakers to regulate AI, in private they have fiercely resisted any form of regulation of foundation models. And research by Corporate Europe Observatory shows they have used their massive lobbying firepower to do so.

So far this year, 66 per cent of meetings on AI involving members of the European Parliament have been with corporate interests—up from 56 per cent over the period 2019-22. From the moment the parliament made clear its intention to regulate foundation models, Big Tech quickly turned its attention to the European Commission and EU member states. This year, fully 86 per cent of meetings on AI of high-level commission officials officials have been with the industry.

Chief executives of Google, OpenAI and Microsoft have all shuttled to Europe to meet policy-makers at the highest level, including commission members and heads of state. Google’s Sundar Pichai even managed to have meetings with three commissioners in just one day.

As artificial-intelligence models are increasingly applied across society, it is becoming clear that these systems carry risks and can harm fundamental rights. Yet Big Tech—driving the AI revolution—is lobbying to stop regulation that could defend the public.

These social impacts are neither hypothetical nor confined to the future. For example, from the Netherlands and the United Kingdom to Australia, biased algorithms have falsely accused thousands of people of defrauding social-security benefits, with disastrous effects on their lives and livelihoods. In the Netherlands this affected tens of thousands, mostly from low-income households and/or a migrant background, driving victims into debt, homelessness and mental ill-health due to the extreme stress they experienced.

Structural biases

Over the last year, discussion has increasingly focused on the most advanced AI systems, known as ‘foundation models’, such as ChatGPT. These can be used for a wide range of purposes. The systems are often complex and behave in ways that can surprise even their own developers. Foundation models are trained on societal data and if the data carry structural biases—from racism to able-ism and more—these risk being baked into the systems.

Because of the scale and amounts of memory, data and hardware required, foundation models are primarily developed by the technology giants, such as Google and Microsoft. These near-monopolies in AI are reinforced through billion-dollar partnerships with ‘start-ups’, such as between Amazon and Anthropic or Microsoft and OpenAI. Tech giants have invested a massive $16.2 billion in OpenAI and Anthropic in the last year. As the AI Now Institute has written, ‘There is no AI without Big Tech.’

Alarmingly, these same firms have recently fired or trimmed down their ethics teams. In some cases these had called out some of the dangers of the systems they were developing.

Because of these risks, in the spring the European Parliament moved to impose certain obligations on companies developing foundation models—basically a duty of due diligence. Companies should show they had done everything they could to mitigate any risks to fundamental rights, check the quality of the data used to train these AI systems against any biases and lower their environmental impact: enormous amounts of electricity and water are used by the data centres.

Massive firepower

While publicly the tech companies have called on lawmakers to regulate AI, in private they have fiercely resisted any form of regulation of foundation models. And research by Corporate Europe Observatory shows they have used their massive lobbying firepower to do so.

So far this year, 66 per cent of meetings on AI involving members of the European Parliament have been with corporate interests—up from 56 per cent over the period 2019-22. From the moment the parliament made clear its intention to regulate foundation models, Big Tech quickly turned its attention to the European Commission and EU member states. This year, fully 86 per cent of meetings on AI of high-level commission officials officials have been with the industry.

Chief executives of Google, OpenAI and Microsoft have all shuttled to Europe to meet policy-makers at the highest level, including commission members and heads of state. Google’s Sundar Pichai even managed to have meetings with three commissioners in just one day.

Unexpected support

Big Tech also received support from an unexpected corner. The European AI start-ups Mistral AI and Aleph Alpha have upped the pressure on their respective national governments, France and Germany.

Mistral AI opened a lobbying office in Brussels over the summer with the former French secretary of state for digital transition, Cédric O—who is known to have the ear of the French president, Emmanuel Macron—in charge of EU relations. O has played a key role in pushing the French government to oppose regulating foundation models in the name of innovation. Along with René Obermann, chair of the aerospace and defence giant Airbus, and Jeannette zu Fürstenberg, founding partner of the tech venture fund La Famiglia, O was one of the initiators of an open letter signed by 150 European companies claiming that the AI Act ‘would jeopardise Europe’s competitiveness and technological sovereignty’.

This lobbying offensive continued after the summer. In October, French, German and Italian officials met representatives from the tech industry to discuss industrial co-operation on AI. After the summit, the German economy minister, Robert Habeck, sounded like a tech spokesperson: ‘We need an innovation-friendly regulation on AI, including general purpose AI.’ Habeck stressed the risk-based approach of the AI Act, a Big Tech talking point to avoid regulating the development of foundation models.

Public interest

The opposition from these member states has severely derailed the the ‘trilogue’ negotiators among the EU institutions. But even when agreement is reached much will remain to be decided—by the commission in implementing acts and by the standard-setting bodies which will steer how precisely the AI Act will be effected. This leaves future avenues for Big Tech to influence the process.

In the run-up to the European elections in June and after a term of unprecedented digital rule-making, the question arises whether Big Tech has become too big to regulate. From surveillance advertising to unaccountable AI systems, with its huge lobbying capacity and privileged access to power, Big Tech has all too often succeeded in preventing regulation which could have reined in its toxic business model.

Just as Big Tobacco was eventually excluded from lobbying public-health officials after years of dirty lobbying tactics, it is time to restrict Big Tech companies from lobbying the EU in their interests—when the public interest is at hazard.

Bram Vranken is a researcher and campaigner at Corporate Europe Observatory (CEO), a Brussels-based lobby watchdog.

Big Tech also received support from an unexpected corner. The European AI start-ups Mistral AI and Aleph Alpha have upped the pressure on their respective national governments, France and Germany.

Mistral AI opened a lobbying office in Brussels over the summer with the former French secretary of state for digital transition, Cédric O—who is known to have the ear of the French president, Emmanuel Macron—in charge of EU relations. O has played a key role in pushing the French government to oppose regulating foundation models in the name of innovation. Along with René Obermann, chair of the aerospace and defence giant Airbus, and Jeannette zu Fürstenberg, founding partner of the tech venture fund La Famiglia, O was one of the initiators of an open letter signed by 150 European companies claiming that the AI Act ‘would jeopardise Europe’s competitiveness and technological sovereignty’.

This lobbying offensive continued after the summer. In October, French, German and Italian officials met representatives from the tech industry to discuss industrial co-operation on AI. After the summit, the German economy minister, Robert Habeck, sounded like a tech spokesperson: ‘We need an innovation-friendly regulation on AI, including general purpose AI.’ Habeck stressed the risk-based approach of the AI Act, a Big Tech talking point to avoid regulating the development of foundation models.

Public interest

The opposition from these member states has severely derailed the the ‘trilogue’ negotiators among the EU institutions. But even when agreement is reached much will remain to be decided—by the commission in implementing acts and by the standard-setting bodies which will steer how precisely the AI Act will be effected. This leaves future avenues for Big Tech to influence the process.

In the run-up to the European elections in June and after a term of unprecedented digital rule-making, the question arises whether Big Tech has become too big to regulate. From surveillance advertising to unaccountable AI systems, with its huge lobbying capacity and privileged access to power, Big Tech has all too often succeeded in preventing regulation which could have reined in its toxic business model.

Just as Big Tobacco was eventually excluded from lobbying public-health officials after years of dirty lobbying tactics, it is time to restrict Big Tech companies from lobbying the EU in their interests—when the public interest is at hazard.

Bram Vranken is a researcher and campaigner at Corporate Europe Observatory (CEO), a Brussels-based lobby watchdog.

No comments:

Post a Comment