Investigators To Examine Whether Dirty Fuel Caused Baltimore Bridge Crash

A safety probe into a Baltimore bridge collapse will determine whether contaminated fuel played a part in the accident whereby a giant ship lost power and crashed into the bridge forcing it to collapse.

Early investigations suggest that the Singapore-flagged Dali cargo ship was setting off from the Port of Baltimore to Colombo, Sri Lanka, when it apparently lost power and crashed into a support pillar of the Francis Scott Key Bridge.

The lights on the Dali, a 948-foot-long container ship capable of carrying 95,000 tonnes of cargo, began to flicker about an hour into the trip, prompting a harbor pilot and assistant to report power issues and a loss of propulsion.

The bridge collapsed on impact and tumbled into the Patapsco River, with the crew managing to send a last-minute mayday call to the police just in time to stop traffic. Emergency responders rescued two people from the water while another six remain missing.

An oil executive has told Fox News there’s some validity to reports that contaminated fuel potentially caused the ship’s engine failure and triggered the accident.

"It's just stealing money, the companies selling them. If nobody's watching closely enough, they'll give them contaminated fuel," United Refining Company CEO John Catsimatidis said in response to a contributor asking how the dirty fuel could get onto the ship.

"Contaminated fuel is being sold to the [New York] schools and sold to the MTA when the MTA or the schools are not watching closely enough. You know, you give them 80 percent real fuel and 20 percent garbage. And the FBI should be looking into that," he added.

Supply chain management company Flexport has warned of a vicious feedback loop and supply chain disruptions following the collapse of the Baltimore Bridge.

“It’s not just the port of Baltimore that’s going to be impacted,” Ryan Petersen, the company’s CEO has said. According to Petersen, the port’s closure in Baltimore, Maryland, was just one factor that will contribute to shipping delays.

By Alex Kimani for Oilprice.com

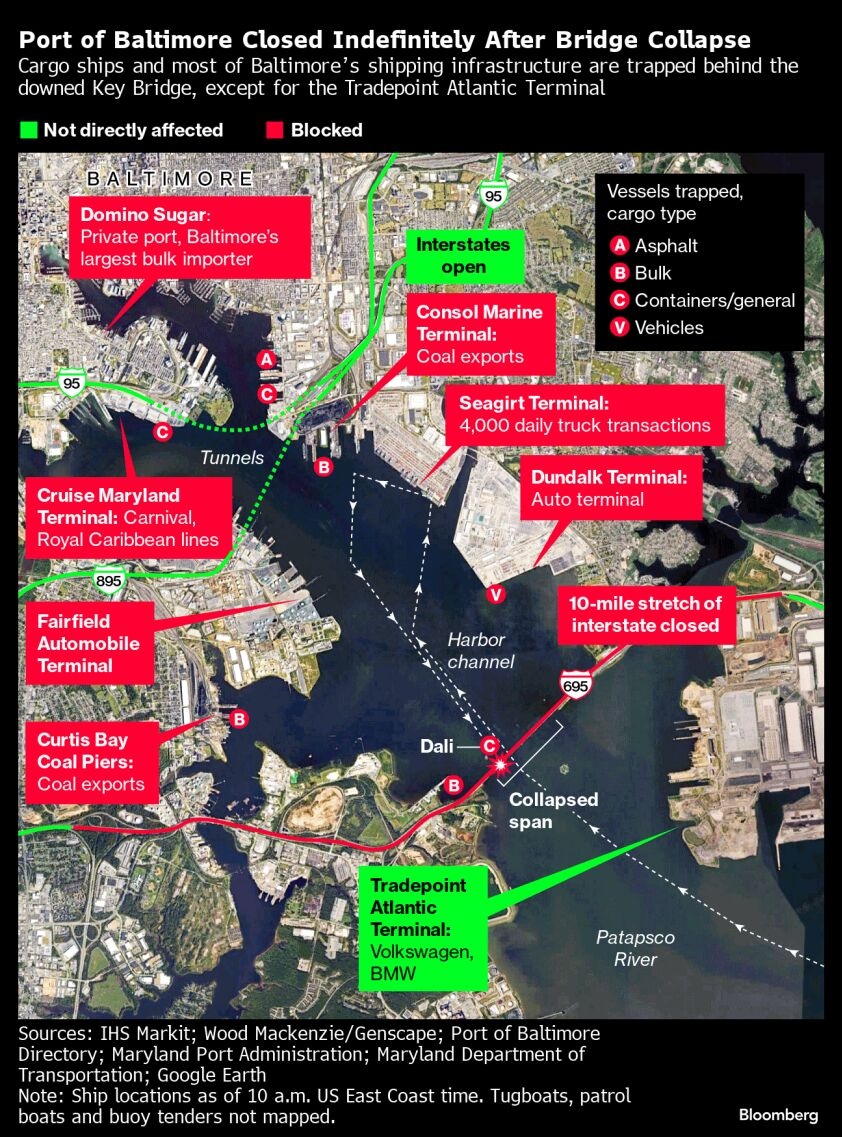

Baltimore's freak bridge collapse reverberates from cars to coal

, Bloomberg News

The 1.6 mile-long bridge collapsed in a matter of seconds. The catastrophic consequences are set to stretch out for weeks.

As much as 2.5 million tons of coal, hundreds of cars made by Ford Motor Co. and General Motors Co., and lumber and gypsum are threatened with disruption after the container ship Dali slammed into and brought down Baltimore’s Francis Scott Key Bridge in the early hours of Tuesday.

Six people were presumed dead after a search in the Patapsco River, officials said Tuesday evening. The toll could have been worse except for a mayday call from the Singaporean-flagged vessel as it lost power.

U.S. National Transportation Safety Board Chair Jennifer Homendy said investigators were able to board the Dali Tuesday night to inspect the ship’s bridge, electronics and documentation.

“We do have the data record, which is essentially the ‘black box,’” Homendy said in an interview with CNN. “We’ve sent that back to our lab to evaluate and begin to develop a timeline of events that led up to the strike on the bridge.”

She added that investigators should have information from the vessel’s black box later on Wednesday.

The aftermath of the bridge’s collapse throws another spotlight on the fragile nature of global supply chains that have already been strained by drought in Panama and missile attacks on Red Sea shipping by Yemen-based Houthi militants. Docks in New Jersey and Virginia face the threat of being overwhelmed by traffic that’s being forced away from Baltimore, one of the busiest ports on the U.S. East Coast.

“It’s a large port with a lot of flow through it, so it’s going to have an impact,” John Lawler, Ford’s chief financial officer, told Bloomberg TV. “We’ll work on the workarounds. We’ll have to divert parts to other ports along the East Coast or elsewhere in the country.”

Baltimore only handled about three per cent of all East Coast and Gulf Coast imports in the year through Jan. 31, said S&P Global Market Intelligence. But it’s crucial to cars and light trucks, with European carmakers such as Mercedes-Benz Group AG, Volkswagen AG and BMW operating facilities in and around the port. It’s also the second-largest terminal for U.S. exports of coal, with a shutdown potentially hitting shipments to India.

About a dozen large vessels are stuck inside Baltimore’s harbour as well as a similar number of tug boats, according to IHS Markit and Wood Mackenzie’s Genscape. The list includes cargo ships, automobile carriers and a tanker named the Palanca Rio.

That’s just the impact on the port.

About 35,000 people used the bridge every day. The annual value of goods going over is about US$28 billion, according to the American Trucking Associations.

“We rely on our infrastructure systems for our daily needs, for a huge amount of the goods that we get in the United States from overseas and to have it cut off so suddenly, it’s a huge crisis,” said Yonah Freemark, a researcher at the Urban Institute.

The Francis Scott Key Bridge, named for the man who wrote the text of the Star-Spangled Banner, took five years to build and was completed in 1977. The cost at the time was around $141 million, according to one estimate. A rebuild today is likely to cost “several billion dollars,” said Freemark.

President Joe Biden said he wants the federal government to pay and vowed “to move heaven and earth to reopen the port and rebuild the bridge.”

But Baltimore is in for a lengthy reconstruction. It could be weeks before any port operations resume as officials need to remove bridge debris and the 984-foot Dali from the river.

That’s expected to accelerate a shift of cargo to the U.S. West Coast to avoid bottlenecks from Boston to Miami. A sudden 10 to 20 per cent increase in volumes through a port is enough to cause massive backlogs and congestion, according to Ryan Petersen, the founder and chief executive officer of Flexport Inc., a digital freight platform based in San Francisco.

Trade hub

Traversing Maryland, meanwhile, threatens to create headaches for motorists and truckers. A trip from Edgemere heading south to Glen Burnie was about 15 miles (24 kilometers) over the bridge. It’s 20 miles via the Baltimore Harbor Tunnel. The trip will be even tougher for truckers hauling hazardous materials, which are barred from the tunnel. They’d have to travel 45 miles on the Baltimore Beltway.

The biggest hit though could be to Baltimore itself, a city of close to 600,000 people whose stagnation and high-poverty neighborhoods were made famous by television show The Wire.

The bridge helped connect major parts of Baltimore and was key to its renaissance as a logistics and e-commerce hub after the shuttering of its steel industry. With its deep-water port, shortline railway and well-located interstate highway, the city attracted investors who have been pouring money into redevelopment.

One of the largest projects, Tradepoint Atlantic, has leased millions of square feet in warehouse space to some of the world’s biggest businesses, including Amazon.com Inc. and FedEx Corp.

Facing months of uncertainty, Baltimore and Maryland both declared a state of emergency.

Throughout the morning on Tuesday, crowds gathered in east Baltimore County, camping out in grassy spots or climbing highway guardrails to get a better look of the bridge and snap photos. Across the street from a Dollar General on Dundalk Avenue, residents discussed the roar of the structure collapsing, comparing it to a jet engine during takeoff.

Not far from the collapsed bridge, police changed shifts at the dock of the Hard Yacht Cafe in Dundalk. Officers getting off their boat had been circling the waters as part of the rescue effort for more than 10 hours, they said, adding that divers were searching for remaining victims in the water when they left the scene.

“This is one of the cathedrals of American infrastructure,” said U.S. Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg. “The path to normalcy will not be easy, it will not be quick, it will not be inexpensive, but we will rebuild together.”

After Bridge Tragedy, One Baltimore Cargo Terminal is Still Open

The tragic collapse of Baltimore's Key Bridge has put a new spotlight on Tradepoint Atlantic, the logistics complex located on the former Bethlehem Steel site. Unlike Baltimore's inner harbor, Tradepoint is seaward of the bridge's wreckage, and it is one of the few parts of the city's waterfront still open to deep-sea traffic.

In a statement, the terminal's operator said that it was working closely with officials as the emergency response proceeds.

"Tradepoint Atlantic has been in constant contact with emergency response officials and leaders from Baltimore City, Baltimore County, and the State of Maryland and will continue to coordinate during this extremely challenging situation," the company said. "As part of the Port of Baltimore, we are committed to helping our state and local partners and the entire port community recover and rebuild from this tragedy."

Tradepoint is a receiving terminal for ro/ro vessels in the Baltimore area, and this is a core part of the Port of Baltimore's trade. The port vies with Brunswick, Georgia for the title of biggest ro/ro port in America - but the vast car terminals and parking lots on the far side of the bridge are currently inaccessible. Carmakers Volkswagen and BMW, which both have receiving facilities at Tradepoint Atlantic, have both said that their Baltimore operations are unaffected by the bridge collapse.

The site's importance is only set to grow in years to come. Tradepoint is working with MSC and TIL to build a container terminal at Sparrows Point, which would increase Baltimore's capacity to handle containerized cargo by 70 percent. Subject to federal approval for dredging, it could be open as soon as 2027.

In the meantime, multiple seaports up and down the East Coast have said that they stand ready to absorb the extra cargo volume from Baltimore. The additional cargo per port is not expected to rival the peak surge levels seen during the late-pandemic import boom. The Port of Virginia, which is just 125 nautical miles to the south of Baltimore, has been investing heavily in expansion and is expected to pick up a substantial share of the slack.

“I don’t think we’ll have a large impact in terms of logistics and shipping moving forward. There might be snafus over the next couple days while issues are being worked through, but I think they’ll be able to overcome that pretty quickly,” said Brent Howard, president of the Baltimore County Chamber of Commerce, speaking to The Hill.

Bill Doyle Comments on Cargo Ship M/V Dali Allision in Port of Baltimore

Special News Feature: Bill Doyle provides insight into the M/V Dali's allision with the Francis Scott Key Bridge. While federal, state and local authorities are on the scene, there is growing speculation about the vessel’s condition and fuel supply.

The 984-foot container ship was transiting the harbor at nine knots when it struck the bridge, and the circumstances of the accident are still under investigation. The ship is owned by Grace Ocean and is registered in Singapore and managed by Synergy Marine.

Six people who were on the bridge are missing and presumed dead. Two others were rescued from the water. Authorities say the eight construction workers were repairing potholes on the bridge. There were 22 Indian nationals and two local pilots aboard the cargo ship.

Multiple Vessels Trapped in Baltimore, Including Sealift Ships

As federal and local authorities focus on the emergency response to the collapse of Baltimore's Francis Scott Key Bridge, Port of Baltimore's inner harbor remains cut off from the rest of the world. No vessels can get in to deliver Baltimore's core cargoes - containers, cars, gypsum and sugar - and no vessels can get out.

The latter fact will be of particular interest for shipowners who have vessels inside the harbor. These include one car carrier, the Swedish-flagged Carmen; four bulkers, the Klara Oldendorff, Balsa 94, Saimaagracht and JY River; and four laid-up ships belonging to the Maritime Administration's Ready Reserve (RRF), the Cape Washington, Gary I. Gordon, SS Antares and SS Denebola.

The Biden administration has restoration of the navigation channel at the top of its list of priorities, Secretary of Transportation Pete Buttigieg said Wednesday.

"We can't wait for the bridge work to be complete to see that channel reopened. There are vessels that are stuck inside right now and there's an enormous amount of traffic that goes through there. That's really important to the entire economy," he told NPR in an interview.

The closure's effect on four RRF vessels could have potential implications for emergency sealift preparedness. The RRF's vessels are kept in reduced operating status at multiple sites around the nation, and the shutdown of any one port would not affect the service's ability to mobilize transport options for most overseas contingencies.

However, two of the vessels in Baltimore are high-value assets - the steamships SS Antares and SS Denebola. These are two out of eight Fast Sealift Ships - a class of SeaLand boxships that were converted for military ro/ro service in the 1980s. They are among the fastest cargo ships in operation today, and their peak speed tops out at 33 knots.

The eight FSS vessels have delivered goods for every major U.S. conflict since the First Gulf War; however, these powerful steamships are 50 years old, and each ship's ability to get under way is not known. The RRF has acknowledged issues with its aging tonnage, and commercially-obsolete steam plants are particularly challenging for MARAD to man and maintain.

Old Lessons May Haunt Baltimore Bridge Tragedy

For observers who have been in shipping long enough, Wednesday's disastrous bridge collapse in Baltimore brought to mind lessons learned in 1980, when the freighter Summit Venture struck and destroyed half of Tampa's Sunshine Skyway bridge. 35 people died in that disaster, prompting a decade-long rethink of highway bridge design. The Skyway Bridge was rebuilt with a fortress of protective concrete dolphins - but it is unclear whether Baltimore's Francis Scott Key Bridge was updated to meet a similar standard before it was hit by the boxship Dali on Wednesday morning.

Baltimore's Key Bridge opened in 1977, three years before the Skyway Bridge disaster (and two years after a similar casualty in Tasmania). Based on visual evidence, the Key Bridge had one small dolphin on each side of the central span's piers, intended either for scour protection or for defending against allisions. When the container ship Dali approached early Wednesday morning, the vessel appeared to pass by the dolphin and strike the pier directly with her starboard bow.

“Maybe [the dolphin] would stop a ferry or something like that,” consulting engineer Donald Dusenberry told the New York Times. “Not a massive, oceangoing cargo ship.”

Tampa-area attorney Steven Yerrid was involved in the response to the Skyway Bridge disaster in 1980, and he told local media that when he saw the fendering system on the Key Bridge, it looked all too familiar. "I felt not only shock, but extreme sadness, because I knew other people had to unnecessarily lose their lives to learn a lesson that was taught 44 years ago," Yarrid told Tampa's Fox 13.

The Skyway Bridge's lessons were written down and codified by AASHTO, America's highway standards body, in 1991. The rules laid out protection requirements for newly-built bridges and guidance for retrofitting old structures. Risks still remained: in 2002, a barge tow hit a pier on the I-40 bridge in Webbers Falls, Oklahoma, destroying the span and killing 14 people. Only the upstream side of the I-40 bridge had structures to protect it from barge traffic - but the casualty vessel approached from the other direction.

For many engineers, the fact that a landmark structure like the Key Bridge could still be felled by marine traffic is a call to action. "As a matter of principle, when there is a bridge pier in a shipping channel we should expect the bridge to be strong enough to withstand impact or to be protected from impact," structural engineer Shankar Nair told the Baltimore Banner.

If the Key Bridge incident ends up in court - as it almost certainly will - the degree of protection around the bridge pier could come up, says José R. Cot, an experienced maritime litigation and insurance attorney at McGlinchey Stafford. Admiralty law presumes that the moving vessel is at fault in an allision, but this can be contested, and the shipowner could argue that the damage would not have been as serious if the pier had had better protection.

"Yes, it could be raised whether it should have been better protected," Cot says. "There has been a historical interest in making fender systems a lot more robust, such that if you have these types of allisions - which are bound to happen - that they do not damage the bridge structure itself. I do think that those representing the vessel interest would probably raise that."

Top image: Sunshine Skyway Bridge, 2007 (Apelbaum / CC BY SA 3.0)

No comments:

Post a Comment