Poll: Most Americans say religion’s influence is waning, and half think that’s bad

There is also growing concern among an array of religious Americans that their beliefs are in conflict with mainstream American culture.

(RNS) — As the U.S. continues to debate the fusion of faith and politics, a sweeping new survey reports that most American adults have a positive view of religion’s role in public life but believe its influence is waning.

The development appears to unsettle at least half of the country, with growing concern among an array of religious Americans that their beliefs are in conflict with mainstream American culture.

That’s according to a new survey unveiled on Friday (March 14) by Pew Research, which was conducted in February and seeks to tease out attitudes regarding the influence of religion on American society.

“We see signs of sort of a growing disconnect between people’s own religious beliefs and their perceptions about the broader culture,” Greg Smith, associate director of research at Pew Research Center, told Religion News Service in an interview.

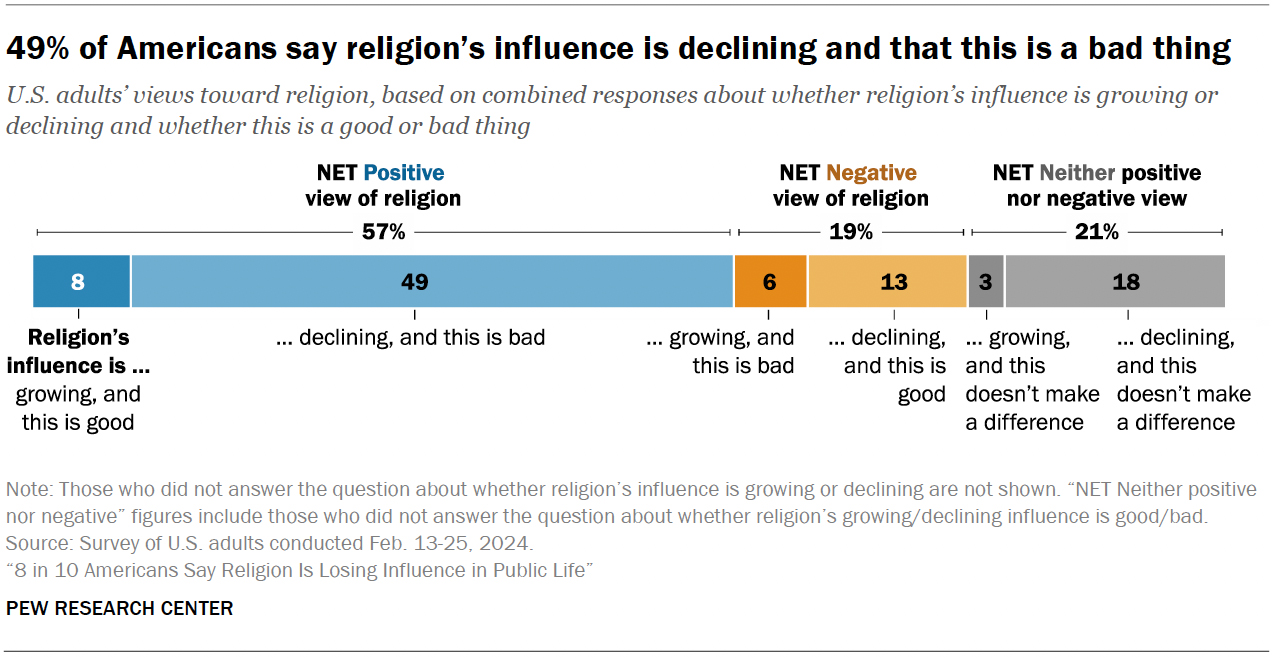

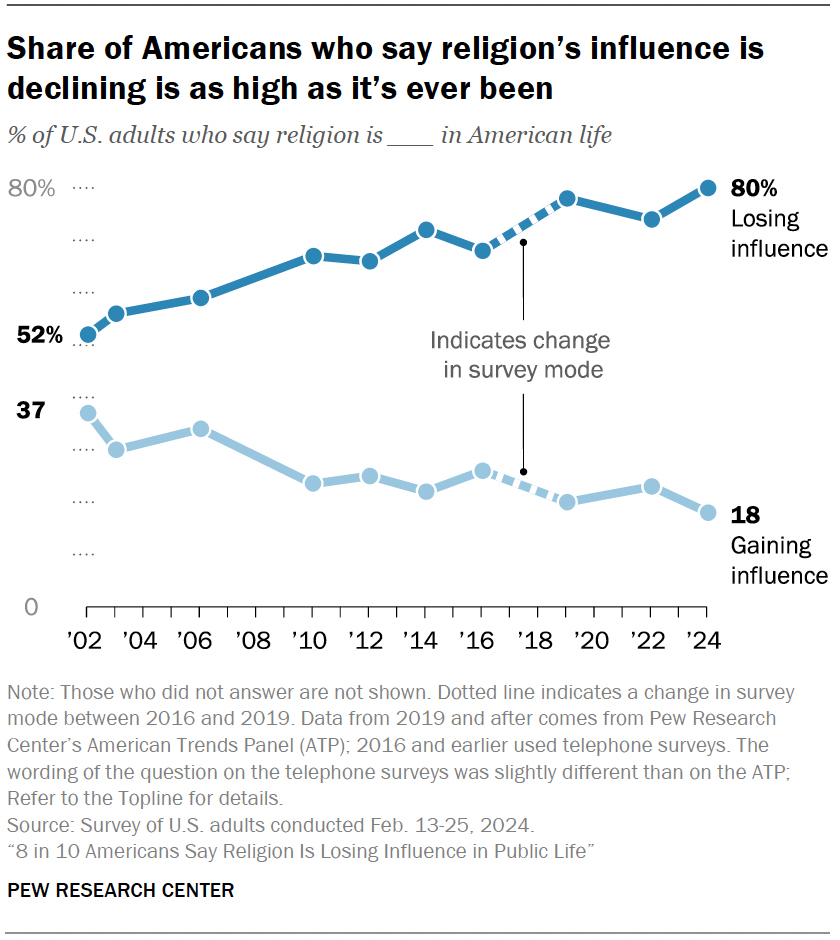

He pointed to findings such as 80% of U.S. adults saying religion’s role in American life is shrinking — as high as it’s ever been in Pew surveys — and 49% of U.S. adults say religion losing that influence is a bad thing.

“49% of Americans say religion’s influence is declining and that this is a bad thing” (Graphic courtesy Pew Research Center)

What’s more, he noted that 48% of U.S. adults say there’s “a great deal” of or “some” conflict between their religious beliefs and mainstream American culture, an increase from 42% in 2020. The number of Americans who see themselves as a minority group because of their religious beliefs has increased as well, rising from 24% in 2020 to 29% this year.

The spike in Americans who see themselves as a religious minority, while small, appears across several faith groups: white evangelical Protestants rose from 32% to 37%, white non-evangelical Protestants from 11% to 16%, white Catholics from 13% to 23%, Hispanic Catholics from 17% to 26% and Jewish Americans from 78% to 83%. Religiously unaffiliated Americans who see themselves as a minority because of their religious beliefs also rose from 21% to 25%.

“We’re seeing an uptick in the share of Americans who think of themselves as a minority because of their religious beliefs,” Smith said.

Researchers also homed in on Christian nationalism, an ideology that often insists the U.S. is given special status by God and usually features support for enshrining a specific kind of Christianity into U.S. law. But while the movement has garnered prominent supporters and vocal critics — as well as backing from political figures such as Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene of Georgia — Pew found views on the subject were virtually unchanged from when they asked Americans about the topic in recent years.

“Share of Americans who say religion’s influence is declining is as high as it’s ever been” (Graphic courtesy Pew Research Center)

“One thing that jumped out at me, given the amount of attention that’s been paid to Christian nationalism in the media and the level of conversation about it, is that the survey finds no change over the last year and half or so in the share of the public who says they’ve heard anything about it,” Smith said.

About 45% of those polled said they had heard of Christian nationalism or read about it, with 54% saying they had never heard of the ideology — the same percentages as in September 2022. Overall, 25% had an unfavorable view of Christian nationalism, whereas only 5% had a favorable view and 6% had neither a favorable nor unfavorable view.

Researchers also pressed respondents on fusions of religion and politics, revealing a spectrum of views. A majority (55%) said the U.S. government should enforce the separation of church and state, whereas 16% said the government should stop enforcing it and another 28% saying neither or had no opinion. Meanwhile, only 13% said the U.S. government should declare Christianity the nation’s official religion, compared to 39% who believed the U.S. should not declare Christianity the state religion or promote Christian moral values. A plurality (44%) sided with a third option: the U.S. should not declare Christianity its official faith, but it should still promote Christian values.

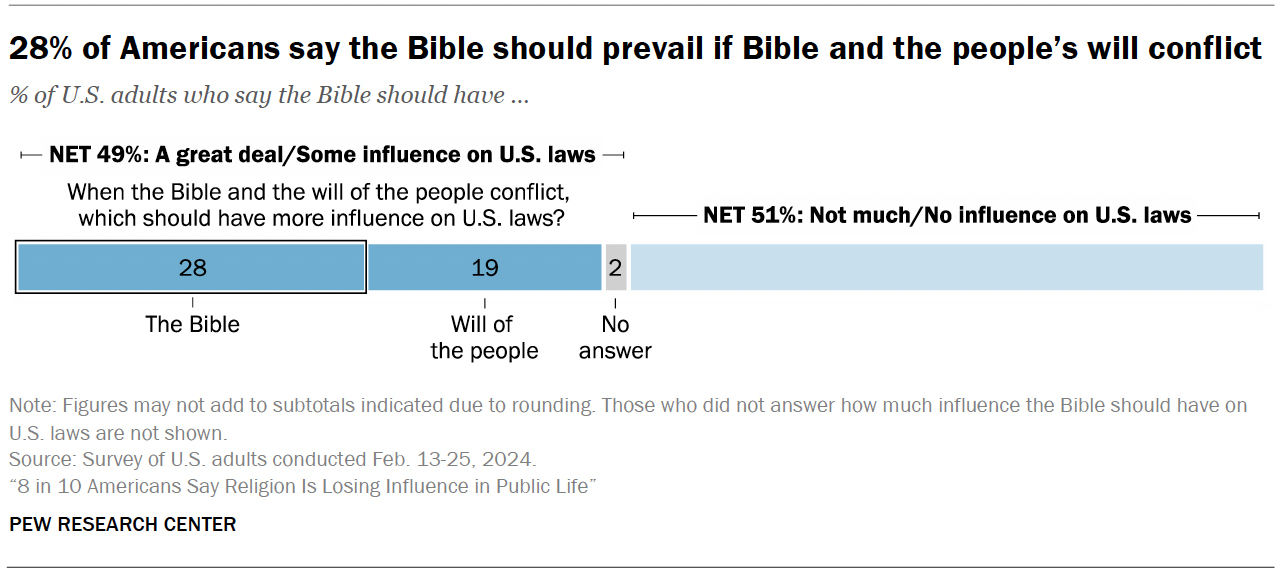

When asked whether the Bible should have influence over U.S. laws, respondents were evenly split: 49% said the Bible should have “a great deal” of or “some” influence, while 51% said it should have “not much” or “no influence.”

But things looked different when Pew asked an additional question of those who supported a Bible-based legal structure: If the Bible and the will of the people come into conflict, which should prevail? Not quite two-thirds of that group — or 28% of Americans overall — said the Bible, but more than a third of the group (or 19% of the U.S. overall) said the will of the people should win out.

“28% of Americans say the Bible should prevail if Bible and the people’s will conflict” (Graphic courtesy Pew Research Center)

Here again, opinions have remained largely static, with researchers noting the numbers “have remained virtually unchanged over the past four years.”

Respondents were also asked whether they believed the Bible currently has influence over U.S. laws, with a majority (57%) agreeing it has at least some. But there were notable differences among religious groups: White evangelicals (48%) and Black Protestants (40%) were the least likely to say the Bible has at least some influence on U.S. law, compared to slight majorities of white non-evangelical Protestants (56%) and both white and Hispanic Catholics (52% for both). The religiously unaffiliated (70%), Jewish Americans (73%), atheists (86%) and agnostics (83%) were the most likely to agree that the Bible is a significant factor in the U.S. legal system.

The survey polled 12,693 U.S. adults from Feb. 13-25.

No comments:

Post a Comment