Published: September 6, 2024

Volcanoes were erupting on the Moon as recently as 120 million years ago, evidence collected by a Chinese spacecraft suggests. Until the last few years, scientists had thought volcanic activity ended on the Moon around 2 billion years ago.

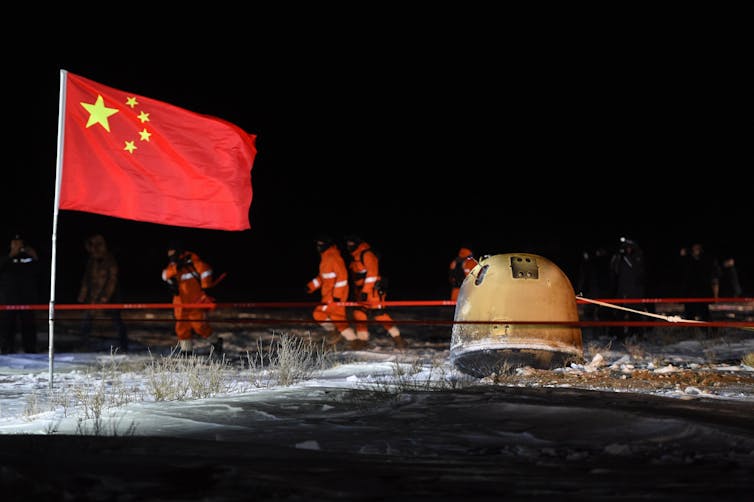

The findings, published in Science, come from analysis of lunar rock and soil delivered to Earth by China’s Chang'e 5 spacecraft in 2020. While these results are difficult to reconcile with the accepted history of lunar volcanism, it’s possible some areas of the Moon’s interior were more enriched in radioactive elements that generate the heat that drives volcanic activity.

The region where Chang'e 5 landed, called Oceanus Procellarum, may be one such area where rocks were enriched in these heat-producing elements.

Volcanism is a major way in which all rocky planetary bodies lose their heat. The rocky bodies in our Solar System are Earth, Venus, Mars, Mercury, Jupiter’s satellite Io, and Earth’s satellite, the Moon.

All available evidence suggests that Venus is currently volcanically active. On Mars, we can date the ages of formation of large lava flows by counting the numbers of impact craters on these flows.

This crater-counting technique relies on the fact that craters form randomly and uniformly across planetary surfaces, so highly cratered terrains are considered older. The results suggest that Mars, which is half the size of Earth, is volcanically active every few million years.

This is expected, because larger bodies conserve heat better than smaller ones. On this basis Mercury, which is a third of Earth’s size, and our Moon, a quarter the size of Earth, should have been volcanically dead for about 2 billion years.

The same should be true of Io, which is similar in size to our Moon. However, tidal forces generated by gravitational interactions with Jupiter give Io an additional, strong heat source. Io is very volcanically active as a result.

The Moon’s dark areas

Most eruptions on the Moon took place near the edges of giant depressions formed early in the Moon’s history by asteroid impacts. Lava flooded the interiors of these basins to form the dark areas on the Moon’s near side. These areas are call maria (singular mare), the Latin for seas, because the flat sheets of lava were mistaken for expanses of water by early observers.

Analyses of the composition and age of samples returned from these mare areas by the six Apollo missions and three Soviet robotic probes were consistent with the belief there had been no geologically recent volcanic activity on the Moon.

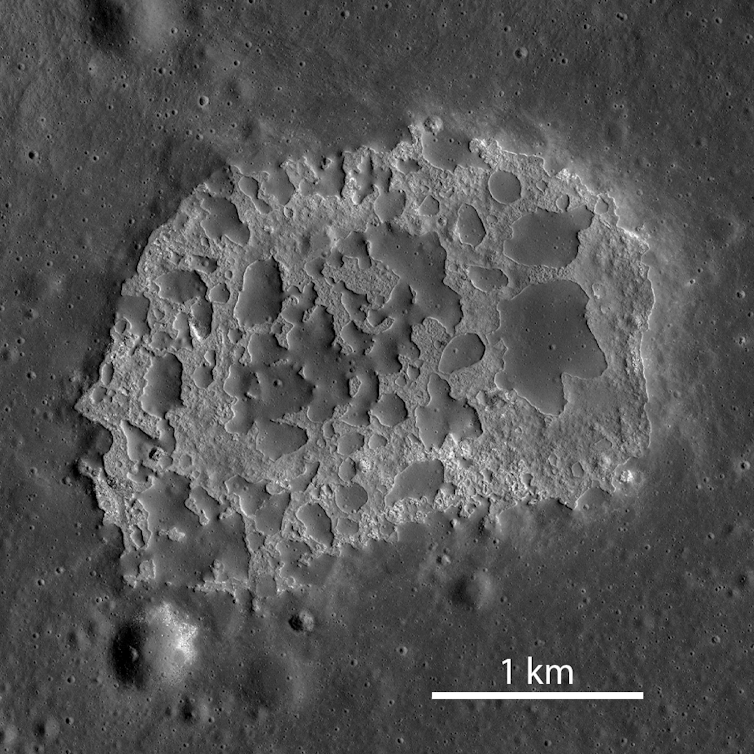

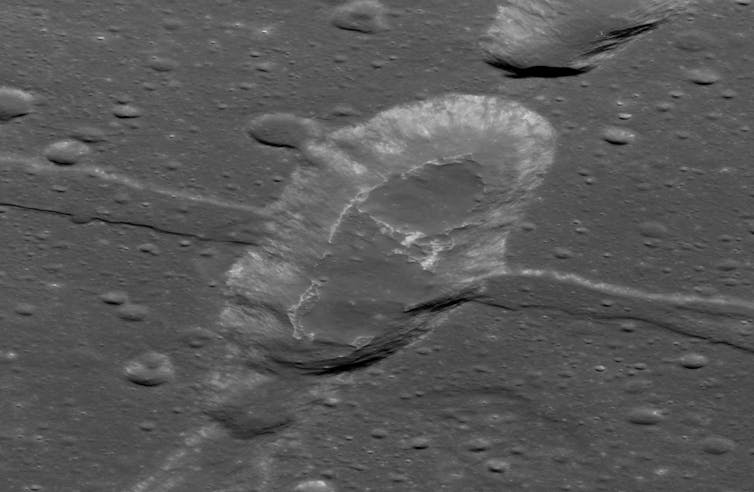

This understanding persisted until very high-resolution images of the lunar surface from the US Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter mission became available following the mission’s launch in 2009. Counts of the numbers of very small impact craters revealed a lack of craters in some volcanic areas with unusual surface textures, named irregular mare patches (IMPs).

The simplest explanation for this was that these IMPs were young, typically about 100 million years old. This is 20 times younger than the 2 billion-year youngest age that had been expected.

In an attempt to reconcile these observations with the accepted history of lunar volcanism, it was pointed out that the lack of any atmosphere on the Moon would make eruptions there significantly different from those on Earth. The lack of confining pressure would have allowed erupting lavas to release almost all of the gaseous compounds dissolved in them, allowing some lava flows to contain very large numbers of gas bubbles – to the extent of being a foam.

Meteoroid impacts into this soft foam would produce much smaller craters than in solid rock, thus causing the crater-counting method to give ages that were too young.

This issue has seen much debate, and the best way to resolve it is the return of samples to Earth for detailed laboratory analysis. Chang'e 5 brought back samples from a very large lava flow which was already known, from crater-counting, to be relatively young in geological terms.

Initial analyses of many fragments of the lava were consistent with the long-accepted theory that lunar volcanism stopped 2 billion years ago. However, closer examination of the Chinese samples, as described in the new Science paper, focused on some of the smallest fragments – the majority from rock shattered and melted into droplets by meteoroid impacts.

Three of these 3,000 droplets were identified from their detailed chemistry as volcanic in origin, and are only 120 million years old – very similar to the young ages inferred for IMPs elsewhere on the Moon.

Lunar eruptions

Lunar eruptions should have involved high lava fountains like those commonly seen erupting in Hawaii, for example. While most of these droplets would have accumulated into lava flows, some would have been thrown out for tens of kilometres to other parts of the Moon’s surface.

The three “volcanic droplets” identified in the Chang'e 5 sample were probably not erupted from the same vent as the bulk of the rock and soil delivered to Earth. This would explain why these droplets are much younger than the lava flow at Chang'e 5’s landing site.

These three glassy droplets are the first physical evidence we have for anomalously recent volcanic activity on the Moon. There would have to have been much higher concentrations of heat-producing radioactive elements in some areas than others for volcanic activity to have occurred as recently as the new results imply. So, these findings could prompt a major revision in our understanding of how the Moon developed.

Disclosure statement

Lionel Wilson has in the past received funding from the Leverhulme Trust for work on lunar volcanism.

"China is likely to become the first country to return samples from Mars."

Stephen Clark

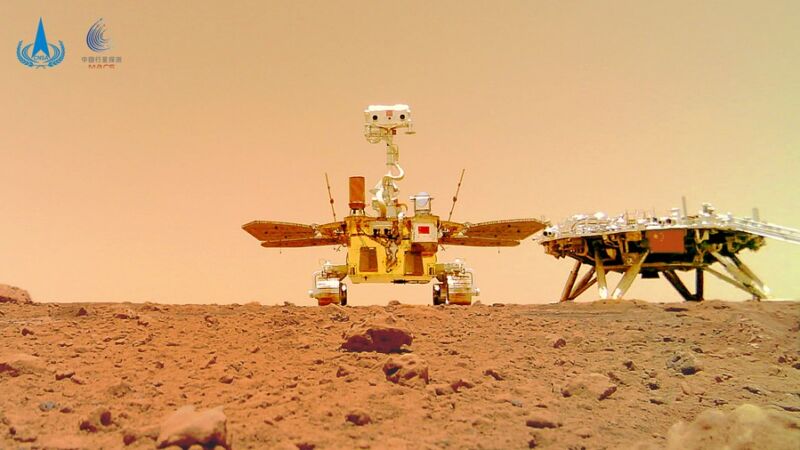

Enlarge / A "selfie" photo of China's Zhurong rover and the Tianwen-1 landing platform on Mars in 2021.

China National Space Administration54

China plans to launch two heavy-lift Long March 5 rockets with elements of the Tianwen-3 Mars sample return mission in 2028, the mission's chief designer said Thursday.

In a presentation at a Chinese space exploration conference, the chief designer of China's robotic Mars sample return project described the mission's high-level design and outlined how the mission will collect samples from the Martian surface. Reports from the talk published on Chinese social media and by state-run news agencies were short on technical details and did not discuss any of the preparations for the mission.

Public pronouncements by Chinese officials on future space missions typically come true, but China is embarking on challenging efforts to explore the Moon and Mars. China aims to land astronauts on the lunar surface by 2030 in a step toward eventually building a Moon base called the International Lunar Research Station.

Liu Jizhong, chief designer of the Tianwen-3 mission, did not say when China could have Mars samples back on Earth. In past updates on the Tianwen-3 mission, the launch date has alternated between 2028 and 2030, and officials previously suggested the round-trip mission would take about three years. This would suggest Mars rocks could return to Earth around 2031, assuming an on-time launch in 2028.

NASA, meanwhile, is in the middle of revamping its architecture for a Mars sample return mission in cooperation with the European Space Agency. In June, NASA tapped seven companies, including SpaceX and Blue Origin, to study ways to return Mars rocks to Earth for less than $11 billion and before 2040, the cost and schedule for NASA's existing plan for Mars sample return.

That is too expensive and too long to wait for Mars sample return, NASA Administrator Bill Nelson said in April. Mars sample return is the highest priority for NASA's planetary science division and has been the subject of planning for decades. The Perseverance rover currently on Mars is gathering several dozen specimens of rock powder, soil, and Martian air in cigar-shaped titanium tubes for eventual return to Earth.

This means China has a shot at becoming the first country to bring pristine samples from Mars back to Earth, and China doesn't intend to stop there.

"If all the missions go as planned, China is likely to become the first country to return samples from Mars," said Wu Weiren, chief designer of China's lunar exploration program, in a July interview with Chinese state television. "And we will explore giant planets, such as Jupiter. We will also explore some of the asteroids, including sample return missions from an asteroid, and build an asteroid defense system."

The asteroid sample return mission is known as Tianwen-2, and is scheduled for launch next year. Tianwen means "questions to heaven."

China doesn't have a mission currently on Mars gathering material for its Tianwen-3 sample return mission. The country's first Mars mission, Tianwen-1, landed on the red planet in May 2021 and deployed a rover named Zhurong. China's space agency hasn't released any update on the rover since 2022, suggesting it may have succumbed to the harsh Martian winter.

So, the Tianwen-3 mission must carry everything it needs to land on Mars, collect samples, package them for return to Earth, and then launch them from the Martian surface back into space. Then, the sample carrier will rendezvous with a return vehicle in orbit around Mars. Once the return spacecraft has the samples, it will break out of Mars orbit, fly across the Solar System, and release a reentry capsule to bring the Mars specimens to the Earth.

All of the kit for the Tianwen-3 mission will launch on two Long March 5 rockets, the most powerful operational launcher in China's fleet. One Long March 5 will launch the lander and ascent vehicle, and another will propel the return spacecraft and Earth reentry capsule toward Mars.

Liu, Tianwen-3's chief designer, said an attempt to retrieve samples from Mars is the most technically challenging space exploration mission since the Apollo program, according to China's state-run Xinhua news agency. Liu said China will adhere to international agreements on planetary protection to safeguard Mars, Earth, and the samples themselves from contamination. The top scientific goal of the Tianwen-3 mission is to search for signs of life, he said.

Tianwen-3 will collect samples with a robotic arm and a subsurface drill, and Chinese officials previously said the mission may carry a helicopter and a mobile robot to capture more diverse Martian materials farther away from the stationary lander.

Liu said China is open to putting international payloads on Tianwen-3 and will collaborate with international scientists to analyze the Martian samples the mission returns to Earth. China is making lunar samples returned by the Chang'e 5 mission available for analysis by international researchers, and Chinese officials have said they anticipate a similar process to loan out samples from the far side of the Moon brought home by the Chang'e 6 mission earlier this year.

Stephen Clark is a space reporter at Ars Technica, covering private space companies and the world’s space agencies. Stephen writes about the nexus of technology, science, policy, and business on and off the planet.

By: Kit Gilchrist September 6, 2024

Webb Telescope data are still turning up more massive galaxies in the early universe than astronomers expect.

NASA / ESA / CSA / Steve Finkelstein (UT Austin)

A multinational team of astronomers has sifted through images from the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) and found that massive galaxies featured in the early universe in greater numbers than anticipated. Their results add to a growing body of evidence for unexpectedly abundant early, high-mass galaxies that has led astronomers to reassess models of galaxy formation and evolution.

As light travels across the expanding universe, its wavelengths shift toward the redder end of the spectrum in what is known as redshift. As a result, distant galaxies, which originally emitted ultraviolet and visible light, appear to us at infrared wavelengths. Thanks to JWST’s sharp infrared vision, more than ever have come into view.

The new study in the Astronomical Journal draws on two sets of JWST observations made in 2022 at both near- and mid-infrared wavelengths. The researchers found 261 massive galaxies in those observations and looked at how their number changes throughout cosmic time.

The team took great care to look only at galaxies whose central supermassive black holes aren’t feeding. The light from gas flowing in toward those black holes can overpower the light from the stars, making galaxies appear more massive than they really are. The light from galaxies with quiet black holes, by contrast, comes almost entirely from stars.

The researchers grouped the galaxies by their distance and found that the number of massive galaxies increases with cosmic time, in line with what galaxy formation models predict. That’s because galaxies need time to grow massive, whether that’s by merging with other galaxies or forming their own stars.

But at great enough distances — that is, when the universe was less than 1.5 billion years old — there’s a surplus of massive galaxies, compared to what’s expected.

That the models break down in the early universe “may not be very surprising,” remarks Claudia Lagos (University of Western Australia), who wasn’t involved in the study. After all, she points out, those models were designed to reproduce observations of the local, present-day universe, not the long-gone one whose redshifted light is picked up by JWST.

Precisely why the results diverge from the models is unclear. The team behind the study proposes two possible explanations. The first is that, early on, gas may have cooled and condensed into stars more efficiently than today. Modern star formation is a sloppy, wasteful process, in which only a fraction of the available mass is transformed into stars. However, this may not always have been so.

NASA / ESA / CSA / STScI; Image Processing: Joseph DePasquale (STScI), Alyssa Pagan (STScI)

As Gerard Mark Voit (Michigan State University), also not involved with the study, spells out, “In today’s galaxies, star formation is self-limiting because of all the energy it releases, but perhaps those limitations don’t kick in until the universe is more than a billion years old.” A streamlined conversion early on would have enabled some galaxies to swell to giant proportions, despite the overall cosmic conditions being very different back then.

A second, alternative explanation is that the mass-to-light ratio of the distant galaxies that JWST observes is lower than in the local universe. Astronomers use this ratio to work out the stellar mass distribution of a galaxy, and from that a host of other properties. Knowing the right ratio is therefore key. The ratio is ultimately an estimate, though, based on theories of star formation, one that is known to vary over time. It might need to be updated in response to these new findings.

Lagos finds the team’s suggestions “very reasonable,” while cautioning that their conclusions are contingent upon accurate estimates of the galaxies’ masses. Were those to have been overestimated, that “would completely wash out the tension with the models.”

To establish whether any of these interpretations hold water, further measurements are needed. The study’s authors point to observations of galaxy clusters as one means of bettering our understanding of star formation efficiencies.

What is apparent is that JWST, floating through space with its golden mirror like some giant cosmic sunflower, is continuing to push boundaries and keep astronomers on their toes. “We are in a new era where all these exquisite observations are making us think very hard about what we're doing and what we truly understand about galaxies and structure formation,” enthuses Lagos, “which is very exciting!”

Blue Origin shifts its plans for New Glenn rocket after NASA postpones Mars mission

NASA is delaying the launch of its ESCAPADE probes to Mars, which means plans for the debut of Blue Origin’s heavy-lift New Glenn rocket will change as well.

New Glenn was previously due to send the twin ESCAPADE spacecraft to Mars as early as next month, but after a review of launch preparations, NASA rescheduled the launch for next spring at the earliest.

Planning for the mission is complicated because of the tight window for launch, necessitated by the alignment of Earth and Mars. Even a small schedule change can result in a months-long delay for liftoff.

After consulting with Blue Origin, the Federal Aviation Administration and range safety managers at the U.S. Space Force, NASA decided to hold off on fueling up the ESCAPADE probes. “The decision was made to avoid significant cost, schedule and technical challenges associated with potentially removing fuel from the spacecraft in the event of a launch delay, which could be caused by a number of factors,” the space agency said today in a mission update.

ESCAPADE — an acronym that stands for “Escape and Plasma Acceleration and Dynamics Explorers” — is a mission designed to study interactions between the solar wind and Mars’ magnetosphere.

“This mission can help us study the atmosphere at Mars — key information as we explore farther and farther into our solar system and need to protect astronauts and spacecraft from space weather,” said Nicky Fox, associate administrator for science at NASA Headquarters. “We’re committed to seeing ESCAPADE safely into space, and I look forward to seeing it off the ground and on its trip to Mars.”

The postponement provides Jeff Bezos’ Blue Origin space venture with additional breathing room as it prepares for New Glenn’s first launch. In a posting to X, the Kent, Wash.-based company said it was supportive of NASA’s decision and would look forward to launching the ESCAPADE probes at a later time.

“We plan to move up New Glenn’s second flight, originally scheduled for December, into November,” Blue Origin said. “New Glenn will carry Blue Ring technology and mark our first National Security Space Launch certification flight. We’ll provide more details on these launch plans in the coming weeks.”

In March, Blue Origin said it would use its Blue Ring orbital logistics vehicle to support a mission known as DarkSky-1 for the Pentagon’s Defense Innovation Unit.

No comments:

Post a Comment