Action needed to improve poor health and disadvantage in the youth justice system

Children and adolescents detained in the youth justice system experience poor health across a range of physical and mental health domains, according to new research.

In the first global review, researchers from the University of Melbourne, Murdoch Children's Research Institute (MCRI) and University of Sheffield in the UK have examined the health of detained adolescents from 245 peer-reviewed journal articles and review publications.

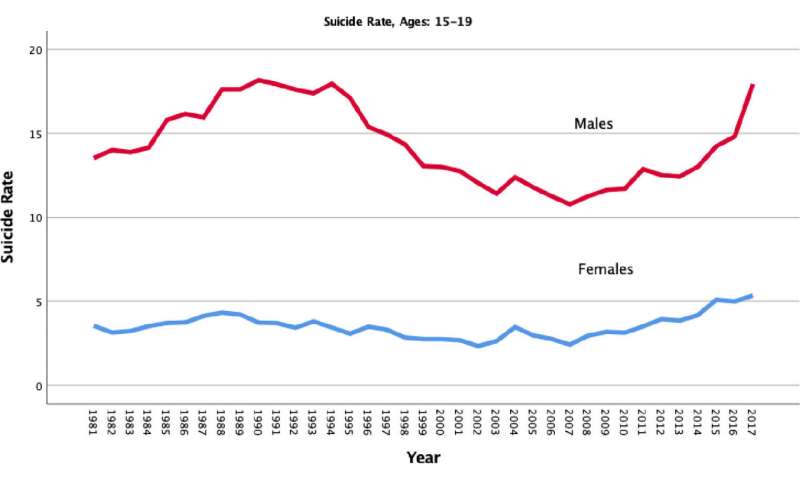

Researchers found that detained adolescents have a significantly higher prevalence of mental health disorders and suicidal behaviours than their peers in the community, along with substance use disorders, neurodevelopment disabilities, and sexually transmitted infections.

In a concurrent paper also published today, researchers examined the ways poor health and poverty drive children into youth justice systems.

Researchers found that learning disabilities, poor mental health, and experiences of trauma and adversity in childhood can increase the risk that a young person will be exposed to the criminal justice system. This risk is further amplified by societal factors including inequality and disadvantage.

University of Sheffield Professor of Adolescent Health and Justice, Nathan Hughes said the research highlights the need for a whole-of-system approach to addressing health and social inequalities in childhood and adolescence.

"Research shows that it is our most disadvantaged and unwell young people who end up in the youth justice system," Professor Hughes said.

"Their health and welfare needs are complex, and many detained adolescents have multiple, co-occurring health issues that are compounded by communication difficulties, risky substance use and trauma."

Head of the Justice Health Unit at the University of Melbourne and MCRI, Professor Stuart Kinner said that to reduce the rates of reoffending and improve health outcomes for vulnerable adolescents and the community, appropriate evidence-based treatment during and after detention must also be provided.

"Investment in coordinated health, education, family, and welfare services for our most disadvantaged young people must be a priority, both to keep them out of the youth justice system, and to ensure that their health and social needs are met if they do end up in detention," Professor Kinner said.

"We need to recognise that these vulnerable young people typically spend only a short time in detention, before returning to the disadvantaged communities from which they have come.

"If we can screen for health and developmental difficulties while adolescents are in the justice system, we can identify unmet needs—often for the first time—and tailor evidence-based support to improve health outcomes and reduce reoffending once they return to the community. However, to make these improvements a reality we need greater investment in transitional programs and public health services."

This research was published today in The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health and The Lancet Public Health.