UKRAINE UPDATE

A Viral Email About Coronavirus Had People Smashing Buses And Blocking Hospitals

Ukraine’s security service said the fake email that was supposedly from the Ministry of Health had actually been sent from outside the country.

Sergei Supinsky / Getty Images

Evacuees look out from a bus as they leave an airport in Kharkiv, Ukraine.

KYIV — A dangerous mix of fear and fake news about the coronavirus has sparked violent protests in Ukraine, despite there being no confirmed cases in the country.

Protests and clashes with riot police have broken out in several places after a mass email claiming to be from Ukraine’s health ministry spread false information that there were five cases of coronavirus in the country, on the same day a plane carrying evacuees from China arrived.

Protesters have smashed the windows of buses carrying evacuees and set fire to makeshift barricades.

Valentyn Ogirenko / Reuter

A stone is thrown towards a police van during a protest against the arrival of evacuees from China.

But the email, sent to the Ministry of Health’s entire contact list, had actually originated from outside Ukraine, the Security Service of Ukraine (SBU) said in a statement.

Only two Ukrainians have been infected with the coronavirus and they are aboard the Diamond Princess cruise ship docked in Japan, and they've already recovered.

Disinformation surrounding the coronavirus has spread online globally and caused panic in other countries ever since the outbreak started in Wuhan, China, in December.

Maksym Mykhailyk / Getty Images

Local residents protest the plans to quarantine evacuees at a local hospital in the settlement of Novi Sanzhary.

In Ukraine, where trust in the health care system and the government is low, anxiety about the outbreak spread as fast as the fake news claiming the first cases had arrived in the country was disseminated online. It didn’t seem to matter that Ukraine’s Center for Public Health put out a message warning of the fake news or that President Volodymyr Zelensky said authorities had everything under control.

“Attention! The reports about five confirmed cases of COVID-19 coronavirus in Ukraine are UNTRUE,” the Center for Public Health said in a statement, referring to the official name of the disease caused by the coronavirus.

“We urge the media not to disseminate this information and to inform the press service of the Health Ministry of Ukraine of the sender of this information upon receipt of the letter.”

Oleksiy Kucher, the governor of the Kharkiv region where the plane carrying Ukrainian evacuees from China’s Hubei province landed, told people, “not to sow panic — everything is fine. All who are on board are healthy.”

But the messages trying to reassure people were not the ones that went viral.

Sergei Supinsky / Getty Images

A medical worker smokes between ambulances during the arrival of evacuees in Kharkiv.

Tensions reached a fever pitch by midday in the village of Novi Sanzhary, in Ukraine’s central Poltava region, where residents protested the arrival of the evacuees over fears they could be infected with the coronavirus, including smashing the windows of buses transporting them.

The protesters fought with police while trying to block the road leading to a health facility where the evacuees — 45 Ukrainians and 27 foreign citizens, as well as 22 crew members and doctors — are to be held in quarantine for at least 14 days to make sure they aren’t carrying the virus.

Videos posted on social media showed hundreds of police in riot gear dragging protesters away and using armored vehicles to move tractors blocking the road.

Valentyn Ogirenko / Reuters

An injured man receives assistance during the protest against the evacuees arriving in Ukraine.

As the skirmish dragged on, Ukraine’s National Guard had to counter what it said was more fake news, this time about the medical staff at Novi Sanzhary’s hospital fleeing the facility.

By evening, the government had dispatched the prime minister, Oleksiy Honcharuk, and the interior minister, Arsen Avakov, to the village to deal with the turmoil.

Maksym Mykhailyk / Getty Images

Protesters in Novi Sanzhary.

Meanwhile, in the western Lviv region, people used tires and cars to block the entrance to a hospital because they were afraid the evacuees could be brought there and their children would get infected.

And in nearby Ternopil, people gathered with a priest on a road to block access to a medical facility and pray that the Ukrainians returning from China would be kept away from it.

“We are praying so that God can help save us from all of this,” said one of the attendees.

“God forbid the virus spreads further,” said another.

President Zelensky said Thursday the authorities were doing everything possible to make sure the virus wouldn’t spread to Ukraine. In a statement posted to Facebook, he called for calm and reassured Ukrainians they weren’t in danger.

Sergei Supinsky / Getty Images

A security officer wearing a protective facemask in Kharkiv.

There is no risk of infection, Zelensky told the nation, only “the danger of forgetting that we are all human and we are all Ukrainians.” He said the panic showed “far from the best side of our character.”

On Facebook, some of the evacuees posted about the harassment they were receiving and said they were shocked by those protesting their return.

One of them, a woman named Svitlana, told BBC’s Ukrainian service that she had received death threats because of her choice to return to Ukraine.

Oleksandr Makhov, who was also aboard the flight, posted a selfie from the plane and praised the flight attendants, pilots, and medics who helped rescue him.

“Shame,” he said of the protesters.

The panic in Ukraine came as China, which has on several occasions changed how it reports new coronavirus infections, said on Thursday it had seen a decrease, according to media reports which cited the country’s health authorities.

The cumulative total of infections globally has reached 75,778 with 2,130 deaths, most in central Hubei province, according to a live tracker from John Hopkins University.

Meanwhile, South Korea reported its first coronavirus death, and Japan reported the deaths of two citizens aboard the Diamond Princess cruise ship.

Nina Jankowicz, a disinformation fellow at the Wilson Center and author of the forthcoming book How to Lose the Information War, told BuzzFeed News from Washington that health-related disinformation and misinformation has huge potential in Ukraine because there is mistrust in the state health care system, which is widely viewed as inefficient and subpar.

“Combine this with mistrust toward official government information sources and a sensationalist media and you have a recipe for panic, especially with a pandemic like coronavirus,” she said.

AMAZON GIG ECONOMY PART 3

3,200 Amazon Drivers Are Going To Lose Their Jobs

Amazon continues to terminate its larger delivery contractors; at least 3,242 delivery drivers will be laid off this spring.

Caroline O'DonovanBuzzFeed News Reporter

Ken Bensinger BuzzFeed News Reporter

Posted on February 27, 2020

Chris Helgren / Reuters

An Amazon worker loads a trolley from a Prime delivery van in Los Angeles, California

More than 3,200 drivers who deliver Amazon packages to homes and businesses across the country each day will be laid off by the end of April as the e-commerce giant continues a significant shift from large delivery contractors to smaller ones that are cheaper and easier to control.

In the past several months, the online retailer has informed at least eight delivery firms that it would be severing contracts with them. In turn, those contractors told state workforce regulators that they would be forced to lay off at least 3,242 employees, records show.

That comes in addition to the layoffs of more than 2,000 drivers from three other terminated delivery firms reported by BuzzFeed News and ProPublica in October; all three of those firms had been involved in accidents resulting in fatalities that were previously reported in investigations by the news organizations.

“Sometimes the companies we contract with to deliver packages do not meet our bar for safety, performance or working conditions,” Amazon said in a statement. “When that happens we have a responsibility to terminate those relationships and work to find new partners. We care a lot about the communities where we operate and work hard to ensure there is zero or very little net job loss in these communities.”

Although Amazon offers laid off drivers the chance to apply for new jobs with its other delivery contractors, the company’s director of transportation compliance, Carey Richardson, recently acknowledged under oath that it’s rare for more than 60% of those individuals to end up at one of those firms. That’s a particular issue at this time of year, when the holiday rush is over and many delivery contractors say they are not hiring.

“There are no jobs for these drivers to transition to,” said the owner of one Amazon delivery firm that has not lost its contract and who requested anonymity for fear of reprisal. “They have nowhere to go.”

To achieve its promise of next-day delivery, Amazon relies on a homegrown network of independent companies that hire their own drivers, rather than employ its own workforce directly. Those contractors, recognizable by their ubiquitous cargo vans that roam the streets of almost every community in the country, delivered more than half of the record number of packages Amazon shipped to customers this past holiday season.

The use of contractors also creates a layer of legal separation that helps Amazon deny liability when things go amiss. Investigations by BuzzFeed News and ProPublica last year found that Amazon contractors have been involved in dozens of serious crashes, including at least ten that were fatal. Many of the online retailer’s delivery firms have been investigated by the Labor Department following allegations that workers were underpaid and denied proper lunch or bathroom breaks.

Using contractors also makes it easy for the online retailer to unilaterally drop firms — many of whom have no other source of revenue and are forced to go out of business — at its whim.

Most recently, Transportation Brokerage Specialists, based in Costa Mesa, California, lost its contract with Amazon and said it would be shutting down its operations in California, Arizona, Washington, and Oregon. As a result, the firm will be forced to initiate a “mass layoff of approximately 907 employees,” the company wrote in a letter to regulators last week.

Amazon has also severed contracts with other contractors, including Bear Down Logistics, Express Parcel Service, Delivery Force, Urban Mobility Now, RailCrew Xpress, Dash Delivery, and 1-800-Courier in recent months, government records show, leading to layoffs in at least 18 states, including California, Texas, Pennsylvania, Georgia, Florida, Ohio, Virginia, North Carolina, Washington, WIsconsin, Massachusetts, Connecticut, Kentucky, Alabama, Michigan, Arizona, Minnesota, and Oregon.

One RailCrew Xpress driver in Alabama was recently told she’d be out of work on April 12. She said she wants to get a job with another Amazon delivery contractor but is far from confident. “I have to apply and hope for the best,” said the woman, who requested anonymity for fear that speaking out would prevent her from getting hired.

After being told he would be laid off because his employer, Delivery Force, was getting terminated by Amazon, one driver got a job offer from a different delivery contractor. But that job paid less, $15 instead of $17 an hour, he said. “It just can’t work,” said the man, who requested anonymity because he is still working for Delivery Force. “It’s so sad,” he added. “We had all these plans for our team … We had no clue until we got the letter.”

Amazon launched its delivery network as an alternative to UPS, FedEx and the US Postal Service in 2014. Originally, it brought in established logistics firms, some of which it contracted to operate in multiple locations and run hundreds or even thousands of routes at a time. But since mid-2018, Amazon has been aggressively shifting its delivery model towards smaller contractors that work from a single location and manage no more than a few dozen routes.

Because of their size, those smaller companies have less negotiating leverage with Amazon, which in some cases pays them as much as 5% less than it paid its so-called “legacy” or “1.0” carriers for the same work, court records show. While Amazon pays legacy carriers a monthly stipend to cover the cost of dispatchers, for example, there is no such payment for the newer firms.

In addition, while legacy contractors are free to choose their own vendors and purchase or lease their own vehicles, Amazon requires its newer carriers, known internally as “2.0,” to lease blue vans branded with the Amazon smile logo, and to obtain insurance and manage payroll through providers that it selects, giving the $900 billion company far more control over their daily operations.

Amazon does not publish a list of all its delivery contractors and in October refused a written request from three US Senators to do so, although it did say it had more than 800 firms under contract at the time. As of late last month, there were roughly 30 legacy contractors still delivering Amazon packages, according to court testimony.

Meanwhile, Amazon continues signing up hundreds of new, small, 2.0 contractors around the country. In its statement, the online retailer said that “in the past six months, more than 300 new Delivery Service Partners have launched their businesses with Amazon, creating job opportunities for nearly 15,000 drivers.”

Drivers at some of the 2.0 firms complain of some of the same workplace issues as at legacy contractors, including being forced to drive poorly maintained vans, not receiving overtime pay, and being denied proper lunch or bathroom breaks. At least one 2.0 firm, Amazing Courier Express Services, based outside San Diego, has been subject to an employment suit, court records show. That suit is still pending.

Last summer, Amazon managers in Seattle reviewed the company’s remaining legacy contractors, ultimately creating a list of 15 firms marked for termination. Amazon manager, Micah McCabe, whose job is to “own the exit process” of delivery contractors, said in court testimony that those 15 firms were singled out solely because they had been named in employment lawsuits by drivers.

But some delivery firm owners claim Amazon’s termination decisions are capricious and inconsistent. A review of court records reveals other legacy firms that have delivered for Amazon for years have been named in multiple employment lawsuits yet do not appear to have been terminated. Courier Distribution Systems, for example, has been sued by its drivers at least 13 times, most recently in November. Yet the Georgia-based firm continues to post help-wanted ads for Amazon drivers, and in some cases offers a wage below the $15 minimum hourly rate Amazon has said it requires its delivery contractors to pay.

A different legacy contractor, Bear Down Logistics, has been the subject of just one employment suit, court records show. But last summer, 75 of its drivers in Wisconsin — frustrated by low pay, inadequate health insurance, and other issues — filed for a labor election that would allow them to be represented by a trade union. Earlier this month, Bloomberg News first reported that Bear Down Logistics had lost its contract with Amazon and as many as 400 drivers would be laid off in April.

When Amazon terminates a delivery firm, it typically offers a payment in exchange for signing a non-disclosure agreement. None of the eight delivery firms that have been terminated responded to requests for comment from BuzzFeed News.

One delivery firm on the termination list, Scoobeez, refused Amazon’s $1 million offer and is currently fighting the online retailer’s efforts to shut it down in court. Scoobeez, based outside of Los Angeles, employs almost 900 drivers in three states and gets essentially all of its income from Amazon; in December 2018 it operated more than 13,000 routes and had $5.1 million in revenue, according to court records.

The delivery firm, which has been working for Amazon since 2015, refused to accept the terms of the 2.0 contract because it “would have taken a 5 percent haircut” on what it earned, according to an email written by Eric Swanson, director of Amazon’s last mile program.

Scoobeez, which has been sued multiple times by workers alleging underpayment and also was accused by its creditors of possible criminal mismanagement, filed for bankruptcy protection last April. Amazon continued giving Scoobeez business after the filing, but in October informed the company that its contract would be terminated.

Amazon, has been unable to cut off Scoobeez because of bankruptcy court protections but contends it shouldn’t be forced to do business with a company it no longer wants delivering its packages, citing concerns that could hurt its reputation.

“If a driver was then to contact media, then Amazon, again, could be called out as the bad guy,” Amazon’s compliance manager Richardson testified. Added McCabe: “I would point to a BuzzFeed article that came out several months ago."

Scoobeez was featured prominently in that article. At least three other firms mentioned in that report have also since been terminated by Amazon since publication.

AMAZON GIG ECONOMY PART 2

New documents and interviews reveal how time after time, the e-commerce giant put speed, profit, and explosive growth before public safety.

AN EXCERPT FROM

“Machine-Oriented System”

By late 2016, Amazon had launched delivery stations in most major metro areas, and it was hurrying to expand to smaller cities in order to keep up with demand. As the critical peak season approached, the pace was straining many contractors.

That fall, Amazon invited representatives from more than a dozen contractors to a New Jersey conference room overlooking Manhattan for the company’s first delivery summit. The meeting was supposed to be a forum for constructive feedback about the program. Instead, attendees recalled, it dragged on for hours as contractors barraged Amazon managers with complaints about nearly every aspect of the system they had created.

Contractors protested that Amazon forced drivers to wait for hours, then overloaded them with boxes and expected them to complete deliveries in an unrealistic time frame. Drivers quit constantly because the job, which often required them to deliver as many as 300 packages a day, was so demanding. Amazon’s unreliable routing and navigation software only made matters worse, according to two people who attended.

Amazon required delivery contractors to use an app called Rabbit, which not only scanned packages but also told drivers which packages to deliver in which order and provided turn-by-turn directions. But the company began using the in-house app before it was ready, former Amazon employees say. After the app’s launch, Trip O’Dell, a design manager, was tasked with heading a team to make improvements to Rabbit, which he described as a work in progress. “In sort of the typical Amazon way where you will try something then stomp on the accelerator, it often ends up ready, fire, aim.”

O’Dell recruited an idealistic band of designers to Amazon with the pitch that they were going to make life on the road better for drivers. But Paula Wood, a member of this group, quickly became disillusioned with the technology and Amazon’s commitment to drivers. “It was ludicrous to expect drivers to be able to deliver in the tiny slices of time,” Wood said. “They put humans into a machine-oriented system.”

Wood said that on many routes, drivers didn’t have enough time to go to the bathroom or eat, so they skipped meals and breaks and urinated in bottles. Navigation directions were terrible, she said. Drivers were, for example, directed to curbs that were no-stopping zones during rush hour. The Rabbit sent drivers on dangerous paths, back and forth across busy roads, she said, full of repeated U-turns and left turns, like the ones that killed Covey and Acerra.

Research shows left turns can be risky because they require the driver to cross oncoming traffic, and the pillar between the windshield and the door can make it harder to see pedestrians in crosswalks. The algorithm that powers the turn-by-turn directions UPS uses, by contrast, programs out most left turns.

One former Amazon manager recalled watching a driver on a ride-along pounding furiously on the phone while shouting: “I hate this Rabbit! I hate this Rabbit!”

The company said there are “hundreds of technologists at Amazon who are focused on continuously improving the functionality of the Rabbit app” and, based on feedback from drivers and contractors, it has made more than 500 changes this year alone. Amazon added that it has “included functionality to avoid left and U-turns, even if that means a route takes longer” and that drivers “have always been able to stop at any time to take a bathroom break.”

Penny Register-Shaw, a former FedEx lawyer, was hired by Amazon in September 2016 to whip the delivery contractor program into shape, according to four people familiar with the program at the time. One of her first orders of business was to attend the New Jersey summit, where at least one contractor said he felt like at last someone was listening and would present the plight of drivers to Amazon management.

But Register-Shaw had trouble persuading her bosses. She spoke gently and slowly, the cadence of her voice reflecting her Tennessee upbringing, and was interrupted so frequently by her new Amazon colleagues that she rarely finished a sentence, according to several people who worked with her.

Register-Shaw and her team proposed changes to make deliveries safer for both drivers and the public, according to interviews with people familiar with the group. They recommended a drug-testing regimen for contractor drivers who were already on the road. The plan called for random tests “so drivers would not know when they were coming,” said a person familiar with the white paper proposing the tests. But the idea was nixed by higher-ups, according to people familiar with the matter.

Asked about this account, Lunak, the Amazon spokesperson, initially said it was false. But when asked additional questions about the company’s drug-testing practices, she explained that Amazon required “comprehensive” preemployment drug screening and said that drivers “are subject to additional screening if there is reasonable cause or if there is an accident.”

At some delivery stations, drivers had to retrieve their vans from distant lots before picking up their packages, and that often put them behind schedule before they even began their routes, according to two people on Register-Shaw’s team. They said her group pushed for closer parking and when that did not happen, the group recommended that drivers’ travel time be taken into account when planning shifts. That idea did not move forward either.

Members of Register-Shaw’s team were mortified by reports of drivers urinating in bottles rather than taking bathroom breaks, and even defecating outside of customers’ homes. “Humans don’t do that unless they’re under tremendous pressure,” a former member of the team said.

In early 2018, an audit team that Register-Shaw had assigned to evaluate the growing pool of delivery contractors working for Amazon reported that it had discovered dozens of the companies were out of compliance.

Some contractors didn’t have the amount of insurance Amazon required, and others weren’t paying for legally mandated overtime and rest breaks, according to several people familiar with the audit.

The findings posed a problem for Udit Madan, the executive Amazon had just put in charge of its last-mile program, according to people familiar with the audit team’s work. Putting as many drivers on the road as possible every day was a priority for Amazon. In one delivery station, the package count nearly doubled overnight, according to a manager who worked there; the e-commerce giant could ill afford to lose established delivery partners to carry those shipments to the customer.

“You felt the pressure,” said a person close to the audit team. “If you take 200 vans off the street, that would have an impact on the customer promise of two-day delivery.”

Register-Shaw eventually took the fall, resigning rather than firing members of the audit team, according to a person familiar with the matter. The head of the audit team was forced out soon after, and the team was dispersed. When asked to comment about the details in this report, Register-Shaw, who now works for Amazon’s largest retail competitor, Walmart, answered, “I wish I could have done more.”

Amazon disputed aspects of this account, saying that its monitoring of delivery contractors has improved since the leadership reshuffle. “Due to issues with the auditing program at the time, the team was moved to a centralized compliance organization,” Amazon said in a statement. “That move and new leadership, created immediate results, including increasing the scope and rate of the audits.”

Madan did not respond to questions sent through an Amazon spokesperson. The company said it monitors its contractors’ compliance with the law and expects those who are not performing to correct their problems within 30 days or “risk having their contract terminated.”

“Our transportation network is not about anyone working faster than is safe,” Amazon said in a statement. “It’s about processes and our overall operations network coming together to be able to serve customers.”

Caroline Gutman for BuzzFeed News

Vans line up to depart after loading at the South San Francisco Amazon facility.

Stuck in the Mud

In June 2018, Amazon invited the news media to Seattle for an event at a picturesque venue overlooking Elliott Bay. Instead of unveiling a new drone or other high-tech project, Dave Clark, standing in front of a van, announced that the company was rebooting its delivery network, shifting much of its package volume to smaller contractors.

The new firms would manage between 20 and 40 routes apiece, compared with hundreds run by the bigger contractors Amazon had previously signed up. Amazon would make it as easy as possible: It helped new delivery companies with legal paperwork, arranged for leases of new vans emblazoned with the company logo and even recommended preferred vendors to handle insurance and payroll. Would-be entrepreneurs — some with no experience in logistics — rushed to sign up for the program, which handed Amazon even more control over nearly every aspect of delivery while also increasing its financial leverage over the tiny firms.

At the same time the program was gearing up, at Amazon managers were putting the final touches on an ambitious road safety plan, the one that aspired to make the company “the safest last mile carrier in the world.”

The July 2018 document, titled "World Wide Amazon Logistics on Road Safety Plan," emphasized that achieving that goal would require a radical shift in the company’s safety culture. Each delivery station, for example, would have a “number of days safe” sign on the wall, all vehicles would be professionally inspected every year for roadworthiness, prospective hires would face more vetting and Amazon would implement a zero-tolerance policy for serious safety violations.

It also detailed the plan in which instructors from the National Traffic Safety Institute would teach new drivers a “defensive driving curriculum.”

“Training is a critical first step to creating the right culture, building a shared vocabulary, and developing the right behaviors,” the plan said.

Although Amazon managers overseeing delivery initially greeted the goals of the safety plan with enthusiasm, according to one person familiar with the plan, their tune changed as the all-important peak season approached.

Between Thanksgiving and Christmas 2018, Amazon roughly doubled its shipments nationwide from the previous year, surpassing the billion package mark for the first time. The company encouraged its delivery contractors to recruit as many drivers as possible. Amazon for its part hired an additional 3,949 employee drivers in the space of just a few weeks, renting “nearly every van in the United States” for them to drive, internal documents show.

In the end, the peak 2018 season looked very little like what the safety team had laid out in its proposal just four months earlier.

Employees charged with inspecting new delivery stations for safety compliance noted in an internal memo that they had been unable to visit every new station prior to launch. In some stations they did manage to visit during peak season, they were chagrined to discover scenes of chaos: inadequately trained managers, severe understaffing, haphazard traffic flows for delivery vans entering and exiting stations, and packages scattered on the floor.

Many of the stations were little more than tents erected in suburban parking lots, referred to internally as “Carnival” stations. Often, the sites suffered from a shortage of bathrooms, unsanitary working conditions, insufficient heat, a lack of ice scrapers for vehicles and poor drainage, according to internal memos and interviews with current and former Amazon employees. Some stations flooded, drivers and packages were “exposed to wind, rain, and snow,” and some parking lots became mired in thick mud that stranded delivery vans. One memo offered a solution for the mud: Put bags of kitty litter in every van.

Human resources employees complained that they “operated with a skeleton crew” while being tasked with recruiting and hiring thousands of seasonal employees who were subsequently taught how to do their jobs by instructors who “lacked the requisite skills to train someone.”

Last January, various departments within Amazon’s logistics operation shared memos detailing “lessons learned” during 2018’s peak season.

Managers overseeing the delivery contractors lamented that there was still “no current metric to measure safety” among their tens of thousands of drivers. During peak, those managers noted, drivers were frequently caught speeding through parking lots, yet there was no way to hold them accountable.

In a memo filed this past January by the group overseeing delivery contractors, one manager warned, “We need a greater focus on safety.”

A group at Amazon responsible for education and training, meanwhile, reported in its memo that it had fallen far short of its hiring goals for driver trainers. Nearly three weeks after peak season ended, 24 delivery stations still didn’t have any driver training at all, the memo said.

In a statement, Amazon said all delivery drivers are required to undergo training “before they are able to deliver even one package.” The company also said that the use of interim facilities such as Carnival stations is “standard practice” in the logistics industry and that it is currently converting those sites into permanent delivery stations.

Internal Amazon documents show that managers in charge of the delivery contractor program worried that the pressure on the system would only intensify during the 2019 holiday rush, as Amazon planned to build 80 new delivery stations, triple the size of its delivery contractor program, and, in April, make overnight delivery the default option for Prime members.

In a memo filed this past January by the group overseeing delivery contractors, one manager warned, “We need a greater focus on safety.”

Bloomberg / Getty Images

Demonstrators hold signs outside Jeff Bezos's penthouse during a protest in New York City on Dec. 2.

Fantastic Plus

Today, Amazon’s delivery operations are under increasing scrutiny as the press, politicians and Amazon’s own former managers question the company’s aggressive approach to logistics.

Citing the BuzzFeed News and ProPublica investigations on the hidden human toll of Amazon’s delivery network, US Sen. Richard Blumenthal in September lambasted the company. On Twitter he called Amazon “callous,” “heartless,” and “morally bankrupt.”

Amazon’s Clark tweeted back, “Senator you have been misinformed.” He wrote that the company took responsibility for its actions and had requirements for safety, insurance, and “numerous other safeguards for our delivery service partners which we regularly audit for compliance.”

A few days later, Blumenthal and two other senators, Sherrod Brown and Elizabeth Warren, demanded answers from Bezos.

“Innocent bystanders — as young as 9 months old — have lost their lives and sustained serious injuries from drivers improperly trained and under immense pressure by Amazon to meet delivery deadlines,” the senators wrote in a September letter to Jeff Bezos. “It is simply unacceptable for Amazon to turn the other way as drivers are forced into potentially unsafe vehicles and given dangerous workloads.”

In the run-up to this year’s peak season, Amazon has adjusted the benchmarks it uses to monitor the performance of its delivery contractors, introducing new safety metrics, according to interviews with delivery contractors and reviews of scorecards used to measure their performance. For example, Amazon began tracking the use of seatbelts by drivers and incorporating that data into weekly scores for delivery businesses. Data is collected through an app that most drivers must use and that monitors speed, acceleration, and braking, among other metrics.

Every week, Amazon rates the performance of its more than 800 delivery contractors. Those that earn the highest scores — identified by Amazon as “fantastic” or “fantastic plus” — receive bonus pay, which some delivery contractors say can represent the difference between losing money or turning a profit.

In a scorecard from November, safety represented 17% of the total score, compared with 33% for a category labeled “quality.” Amazon said that if a delivery contractor doesn’t have a high combined score in its safety and compliance metrics, it cannot reach “fantastic” or “fantastic plus” overall, and that firms that consistently receive low scores can be threatened with termination or see their routes reduced.

In the end, Bezos didn’t reply to the senators’ letter. Instead, a company lobbyist did. He wrote that Amazon empowered hundreds of small businesses through its delivery contractor program and outlined safety and labor compliance tools that he said went far beyond what’s required by law.

“Safety,” the lobbyist wrote, “is Amazon’s top priority.”

One month after that letter was sent, a contractor delivering Amazon packages in a suburban Chicago townhouse complex turned left on a private drive, striking a toddler who had wandered into a puddle in the roadway.

“She didn’t see him,” said Deputy Chief Ron Wilke of the Lisle Police Department, which is still investigating the crash.

The 23-month-old boy died at the hospital that same day. ●

MORE ON THIS

Amazon’s Next-Day Delivery Has Brought Chaos And Carnage To America’s Streets — But The World’s Biggest Retailer Has A System To Escape The Blame Caroline O'Donovan · Aug. 31, 2019

Amazon Is Firing Its Delivery Firms Following People's Deaths Ken Bensinger · Oct. 11, 2019

Ken Bensinger is an investigative reporter for BuzzFeed News and is based in Los Angeles. He is the author of "Red Card," on the FIFA scandal. His DMs are open.

Caroline O'Donovan is a senior technology reporter for BuzzFeed News and is based in San Francisco.

James Bandler is a senior reporter covering business and finance at ProPublica

Patricia Callahan is a senior reporter covering business for ProPublica.

Doris Burke is a research reporter at ProPublica.

Last updated on December 24, 2019, at 4:23 p.m. ET

AMAZON GIG ECONOMY PART 1 AN EXCERPT

Amazon’s Next-Day Delivery Has Brought Chaos And Carnage To America’s Streets — But The World’s Biggest Retailer Has A System To Escape The Blame

Deaths and devastating injuries. A litany of labor violations. Drivers forced to urinate in their vans. Here is how Amazon’s gigantic, decentralized, next-day delivery network brought chaos, exploitation, and danger to communities across America.

Last updated on September 6, 2019

But despite Inpax’s checkered record, after denying any blame for Escamilla’s death, Amazon continued using the company to deliver its packages across Chicago and at least four other major cities. Inpax did not respond to a detailed written request for comment.

The super-pressurized, chaotic atmosphere leading up to that tragedy was hardly unique to Inpax, to Chicago, or to the holiday crunch. Amazon is the biggest retailer on the planet — with customers in 180 countries — and in its relentless bid to offer ever-faster delivery at ever-lower costs, it has built a national delivery system from the ground up. In under six years, Amazon has created a sprawling, decentralized network of thousands of vans operating in and around nearly every major metropolitan area in the country, dropping nearly 5 million packages on America’s doorsteps seven days a week.

Amazon drivers say they often have to deliver upward of 250 packages a day — and sometimes far more than that — which works out to a dizzying pace of less than two minutes per package based on an eight-hour shift.

“The damages, if any, were caused, in whole or in part, by third parties not under the direction or control of Amazon.com.”

The system sheds costs and liability, even as it grows at lightning speed, by using stand-alone companies such as Inpax to pick up packages directly from Amazon facilities and deliver them to the consumer — covering what’s known in the industry as “the last mile.” Amazon goes further than gig economy companies such as Uber, which insist its drivers are independent contractors with no rights as employees. By contracting instead with third-party companies, which in turn employ drivers, Amazon divorces itself from the people delivering its packages.

That means when things go wrong, as they often do under the intense pressure created by Amazon’s punishing targets — when workers are abused or underpaid, when overstretched delivery companies fall into bankruptcy, or when innocent people are killed or maimed by errant drivers — the system allows Amazon to wash its hands of any responsibility.

Amazon still relies on UPS and the US Postal Service for many deliveries. And it has captured the public imagination with press releases about futuristic drone delivery, which does not yet exist. But it’s this homegrown network that makes it possible to offer the amazing convenience of next-day and even same-day delivery that has become a cornerstone of its market dominance. By some estimates, nearly half of Amazon's packages in the US are now delivered this way. And the Seattle-based giant dictates almost every aspect of that operation, down to what drivers wear, what vans they use, what routes they follow, and how many packages they must deliver each day.

Amazon says its role is to lend entrepreneurs a hand as they build small businesses and not to control their companies, equipment, or labor force. It said it does not make personnel decisions for them, and while it offers them the opportunity to lease vans, purchase insurance, and manage payroll through its preferred programs, they are free to use whichever vendors they choose.

Have you had experiences with Amazon or a company contracted by Amazon that you would like to share? To learn how to reach us securely, go to tips.buzzfeed.com. You can also email us at tips@buzzfeed.com.

In response to a detailed list of questions from BuzzFeed News, it said that because many of the cases mentioned in this article are in active litigation, it cannot discuss them in detail. However, the company said safety is always its top priority and that even one serious incident is too many. It says that when accidents occur, it works with drivers or their employers to investigate claims and take appropriate actions.

In a written statement about the article's findings, the company said:

The assertions do not provide an accurate representation of Amazon’s commitment to safety and all the measures we take to ensure millions of packages are delivered to customers without incident. Whether it’s state-of-the art telemetrics and advanced safety technology in last-mile vans, driver safety training programs, or continuous improvements within our mapping and routing technology, we have invested tens of millions of dollars in safety mechanisms across our network, and regularly communicate safety best practices to drivers. We are committed to greater investments and management focus to continuously improve our safety performance.

Six days after publication of this article, Amazon issued an additional statement: "We require that all delivery service partners maintain comprehensive insurance, including auto liability so if in the rare case an accident does occur, there is coverage for all involved."

UPS and FedEx, the traditional powers of the logistics world, are deeply invested in safety. UPS, which spends $175 million a year on safety training alone, even has a policy prohibiting drivers from taking unnecessary left turns to reduce exposure to oncoming traffic, finish routes faster, and save fuel. Both firms are also heavily regulated by the government, and many of their trucks are subject to regular federal safety inspections and can be put out of service at any time by the Department of Transportation.

But Amazon’s ingenious system has allowed it to avoid that kind of scrutiny. There is no public listing of which firms are part of its delivery network, and the ubiquitous cargo vans their drivers use are not subject to DOT oversight. But by interviewing drivers as well as reviewing job boards, classified listings, online forums, lawsuits, and media reports, BuzzFeed News identified at least 250 companies that appear to work or have worked as contracted delivery providers for Amazon. The company said it has enabled the creation of at least 200 new delivery firms in the past year, a third of which are owned and run by military veterans. Inpax gets fully 70% of its business from Amazon; some companies depend on the retail giant for all of their income.

With little training, and often piloting vans in dangerous states of disrepair, Amazon drivers have crashed into cars, bicycles, houses, people, and pets.

A yearlong investigation — based on that data, along with internal documents, government records, thousands of court files, and interviews with dozens of current and former Amazon employees, delivery company operators, managers, and drivers — reveals that Amazon’s pivot to delivery has, all too often, exposed communities across the country to chaos, exploitative working conditions, and, in many cases, peril.

Public records document hundreds of road wrecks involving vehicles delivering Amazon packages in the past five years, with Amazon itself named as a defendant in at least 100 lawsuits filed in the wake of accidents, including at least six fatalities and numerous serious injuries. This is almost certainly a vast undercount, as many accidents involving vehicles carrying Amazon packages are not reported in a way that can link them to the company. And in some states, including California, accident reports are not public.

The deaths have included victims as old as Escamilla and as young as a 10-month-old baby named Gabrielle. Often with little training, and at times piloting vans in dangerous states of disrepair, Amazon drivers have crashed into cars, bicycles, houses, people, and pets. And under constant pressure to deliver ever more packages, drivers have piled parcels so high on their dashboards that they couldn’t see out the windshield — causing at least one serious collision.

Caroline O'Donovan / BuzzFeed News

A delivery vehicle with packages lined along the dashboard, seen in Chicago.

In some of the cases in which Amazon was sued over road accidents, the drivers had been allowed to take the wheel despite previous convictions for traffic infractions.

Delivering packages for Amazon can itself be a perilous job. Drivers have reportedly been punched, bitten, carjacked, robbed, and shot — and at least two have died in recent years as a result of road accidents that occurred on the job.

Amazon denies any responsibility for the conditions in which drivers work, but it has continued to contract with at least a dozen companies that have been repeatedly sued or cited by regulators for alleged labor violations, including failing to pay overtime, denying workers breaks, discrimination, sexual harassment, and other forms of employee mistreatment.

And when one group in Michigan voted to join the teamsters in protest against shoddy conditions and punishing hours without overtime pay, Amazon officials acted swiftly to counter further unionization efforts.

In Southern California, Illinois, and Texas, Amazon continues to work with a firm beset by a staggering array of lawsuits from its own drivers, who said they weren’t paid properly, and from pedestrians, motorists, and cyclists, who said they were injured in collisions with the company’s trucks — even after its chief executive was accused by the firm’s own CFO of embezzling more than $1.5 million to fund an apparent gambling spree in Las Vegas.

Two drivers for a different delivery company operating in the Los Angeles area said they were forced to skip meals, ordered to urinate in bottles rather than stop for bathroom breaks, and advised to speed and not wear seatbelts to ensure they delivered more packages in less time.

Scott Olson / Getty Images

A UPS worker delivers packages on Dec. 26, 2013, in Chicago.

Amazon’s gargantuan delivery network was born after a notorious incident remembered in the corridors of the company’s Seattle headquarters as the “Christmas Fiasco” of 2013. As e-commerce began to boom and the holiday loomed, UPS and FedEx, which then delivered the bulk of Amazon’s packages along with the US Postal Service, were blindsided by the large volume of online orders and failed to deliver many parcels by Dec. 25.

Furious, embarrassed, and determined that such an incident would never happen again, Amazon gave affected customers $20 gift cards while its executives hatched a bold and disruptive plan to free themselves from overdependence on the large, established carriers. They would develop a network of small and midsize delivery companies to take over key routes, working directly out of special Amazon delivery stations, rather than UPS or FedEx facilities, and delivering packages according to Amazon’s own routing algorithms.

The goal, according to people with knowledge of Amazon’s operations — including a former executive who helped oversee the program in its early days — was to build out a completely independent last-mile delivery system. The company said it did so because of growing demand from customers, but continues to work with established delivery companies as well.

Obtained by BuzzFeed News

Amazon would offer small delivery companies, many of them brand-new, a chunk of its booming e-commerce business, and in exchange would be able to wield unprecedented leverage over their logistics operations. It would also have the power to squeeze costs down in a way it never could working with behemoths such as FedEx and UPS.

Under this new system, Amazon would be able to closely monitor drivers through its routing software. It would make entrepreneurs assume the financial risk of running a delivery business. And perhaps most crucially, because the drivers would be employed by independent companies, Amazon would be able to assert it had no legal liability for their working conditions — or for any mayhem employees wrought as they raced to hit delivery targets requiring more than 99% of packages to arrive by their promised delivery date.

In short order, fleets of anonymous-looking gray-and-white vans were dashing through the streets of communities across America, stopping every few blocks to disgorge books, electronic gadgets, boxes of toilet paper, and the myriad other items that people increasingly order online.

In short order, fleets of anonymous-looking gray-and-white vans were dashing through the streets of communities across America.

For consumers, the change was hardly perceptible — unless they happened to look out their windows and notice that the familiar brown of the UPS truck and the cheerful orange and purple of FedEx came less often, replaced by slightly smaller vans that often had no markings at all.

But behind the wheel, and out on the streets, the changes were enormous.

Even though the Sprinter-style vans Amazon requires its delivery providers to use weigh several times more than most passenger cars, they fall just under the weight limit that would subject them and their drivers to Department of Transportation oversight, unlike most FedEx and UPS trucks.

In a sign of how business is booming, Amazon last summer bought 20,000 of these vans from Mercedes-Benz to be leased, through fleet managers, to its dedicated delivery companies around the country.

UPS Package Car

26,000 lbs gross vehicle weight rating

Drivers must have valid driver's license and are subject to medical exams and controlled substance testing.

Trucks are subject to regular inspection, repair, and maintenance, as well as service hours restrictions.

Ford Transit 250

9,100 lbs gross vehicle weight rating

Drivers must have valid driver's license.

Vans are subject to yearly state inspection.

Applicants for jobs at UPS and FedEx are thoroughly screened and cram for challenging entrance exams before being hired. They undergo rigorous training that can last for weeks or longer, depending on the position, and are required to undergo additional training every year. Even the most minor fender benders trigger internal investigations that seek to identify who was at fault and how such accidents can be avoided in the future.

UPS, which is unionized, uses routing software programmed to minimize most left-hand and other dangerous turns. As part of their training, its drivers must go through special protocols before making certain maneuvers, such as backing up their trucks.

Amazon says it spends tens of millions of dollars on safety, and in some of its contracts with delivery companies, it demands that every driver pass a background check and drug test, have at least six months’ experience, and pass an extended road test. Job postings by firms delivering Amazon packages, however, say commercial driver's licenses and prior experience aren’t necessary. Drivers are paid either a flat day rate or an hourly wage — which generally works out to between $15 and $18 an hour, with scant perks or benefits. With constant alternation between driving and loading and unloading packages, the job is physically demanding.

One of the first companies ushered in under Amazon’s new delivery regime was Progistics Distribution, an already operating San Francisco–based logistics firm that agreed to dedicate a portion of its fleet to Amazon packages. Jose Guillermo Perez was hired by the company as a driver in spring of 2014, soon after the Christmas Fiasco.

After two days of in-office training, Perez was sent onto the hilly, chaotic streets of San Francisco riding shotgun alongside a more experienced driver to learn the ropes. Things almost immediately went haywire. Just after lunch on the first day, Perez was astonished to find the driver backing into a light post, then speeding away from the scene as if the accident hadn’t happened, without even checking for damage. After that, Perez said in an interview, things got worse. The driver continued to ignore the speed limit and blew through stop signs as he shot up and down traffic-choked streets.

“Dude, you need to be careful; I want to get back safe,” Perez recalled saying. “I don’t want to die, man.”

But the driver, Jim Kitamura, told Perez he had to hurry.

Shortly after 3 p.m., their Ford van approached a busy intersection in a residential neighborhood just as the light turned red. Rather than hit the brakes, Kitamura kept going, heading straight for a motorcycle that was accelerating through the crossing. A driver in another car noticed and honked frantically in warning, but the delivery van kept going and smashed into the bike, according to a police report.

The impact was so powerful that it not only knocked Paul Hon Chow Lee off the motorcycle — fracturing his ankle, pelvis, and six ribs — but also knocked his shoes clean off his feet, according to the police report.

Even before the crash, the events of the day had given Perez cause for alarm. He saw that drivers were given huge piles of packages to deliver and were barraged by constant nagging calls from dispatchers checking in on their progress. The vans, he thought, were in terrible shape, with worn tires and sagging suspensions, and he said he’d witnessed at least one driver smoking marijuana on the job. Perez said Progistics hadn’t done a drug test on him, and could not recall any other screening process.

Progistics did not respond to a detailed request for comment.

Police cited Kitamura for running a red light. It was far from his first driving violation. In the eight years leading up to the accident, Kitamura had been pulled over at least four times, records show, twice pleading guilty to driving more than 20 mph over the speed limit — once in 2006 and once in 2008 — and once to running a stop sign in 2011. He’d also been charged with sex crimes involving minors and was a registered sex offender.

So concluded Perez’s training.

The first day he was sent out on his own, he quit before the shift was over.

“I thought, No, this is crazy. I had 160 packages and it was raining; you can’t even see,” he said. “I did, like, probably half of it and I took the truck back and went and told the guy, ‘This is it. I’m done.’”

BuzzFeed News

Workers unload packages onto the street for delivery in New York City on Aug. 30.

In the five years since it dove into last-mile delivery, Amazon’s business has boomed.

In 2018, its retail sales hit a record $233 billion, and this year it surpassed Walmart as the largest retailer in the world. In April, it promised free one-day shipping for all its Prime members — an unprecedented logistical challenge.

Not all of Amazon’s packages are carried by its network of small providers; it continues to rely on UPS and the US Postal Service for many of its deliveries, particularly for bulky packages or for rural, harder-to-reach destinations. But with FedEx recently canceling its contract to deliver Amazon packages, a growing share of the huge delivery load is being carried by the network of tiny, lightly regulated firms in its vast national network.

Delivering billions of packages a year is by far one of the company’s top expenditures. But Amazon can better control those costs by squeezing its own delivery network. It not only can track every package but also can monitor payroll, insurance, and even van leasing costs for many of its delivery companies. That allows it to keep an eye on companies’ profit margins and adjust accordingly. Early this year, for example, Amazon stopped paying delivery companies extra money to cover the cost of a dispatcher in each delivery station, requiring the companies to pay that salary out of already thin margins or operate without them.

Amazon pays many of its delivery firms a flat fee per route, so when package volumes increase and drivers need to be out on the road for longer, racking up more overtime, their margins are squeezed even tighter. One contract for a route in San Francisco reviewed by BuzzFeed News, for example, called for a fee of $279.50 per day. That money must cover the cost of the van, insurance, and any other overhead, plus the driver’s wages. Some newer delivery firms are paid a per-route fee, plus a per-package fee.

Many of them have no source of income other than Amazon and, faced with those circumstances, can find they have no choice but to cut back wherever they can.

Obtained by BuzzFeed News

A taped-on rearview mirror and balding tires on a delivery vehicle.

Drivers complain of poorly maintained vans, with underinflated and balding tires, cracked or missing sideview mirrors, and, in one case, doors that had to be held shut with bungee cords. Frequently they have no backup cameras, and many don’t even have a rear window. As a result, some drivers back into things — lawns, mailboxes, parked cars, and, sometimes, people.

And then there are the corners drivers themselves cut to finish their deliveries on time and keep dispatchers off their backs. Drivers complain they are sometimes given so many packages that they don't all fit in the cargo area and must be piled on the passenger seat. Some said they pile packages on the dashboard to save the time it takes to walk around to the rear of their vans for each delivery. Having the parcels laid out at their fingertips, they explained, helps them get through their routes more quickly and avoid the wrath of impatient dispatchers. But that convenience comes at a cost.

Resty Evinger was pulling out of a parking space outside an apartment complex in Austin in March 2018 when she collided with Julia Barrera Duran. The 62-year-old was knocked to the ground, and her head hit the asphalt. According to claims in a pending lawsuit filed by Duran, Evinger had her left foot in a medical boot and walked with crutches. She quickly got out of the Dodge Ram van and knelt by Duran’s side. According to a police report, Evinger explained why she hadn’t seen Duran in broad daylight: Her view had been partially obstructed by a pile of Amazon packages arranged on the dashboard.

Amazon said that it considers a variety of factors when considering the size of loads, but said it is up to drivers to determine how to pack the vans and where to put the packages. If a driver is worried about the number of packages they are given, they are welcome to raise those concerns.

Scoobeez / Via instagram.com

Amazon can surveil almost every driver in its delivery network. But when it comes to the pedigree of the companies it entrusts to deliver its cargo, officials are remarkably hands-off, overlooking serious safety lapses, criminal convictions, and egregious violations of labor laws.

Amazon said it expects its delivery operators to comply with the law.

In July 2015, an obscure mining firm in Idaho abruptly changed ownership and announced it was getting into the package delivery business for Amazon, under the unlikely new name of Scoobeez.

Just months after making its first deliveries, however, the company was sued by four drivers who successfully claimed they had been misclassified as contractors rather than employees. It would be the first in a string of employment, personal injury, contract, and workplace discrimination lawsuits filed against the firm.

In March 2017, the company’s CFO sent a 25-page report to the Scoobeez board of directors alleging that CEO Shahan Ohanessian had misappropriated as much as $1.5 million of the company’s funds, transferring the money to his own bank accounts and withdrawing hundreds of thousand of dollars of that money at the Wynn hotel and casino in Las Vegas. Subsequent investigations concluded that Ohanessian then took out 17 high-interest loans to cover his tracks, costing the company some $2 million in fees and interest payments — money that might have been used to pay the drivers who were suing the company for unpaid overtime or, for example, the Texas family who came home one day to find that a Scoobeez van had rolled down their driveway and into their house, smashing the side of their attached garage.

In April, Scoobeez filed for bankruptcy protection, listing, among other liabilities, monthly payments totaling nearly $7,000 for leased Bentley, Porsche, and Mercedes-Benz luxury vehicles that were made available to the company’s top executives.

Scoobeez denied, in a separate court filing, the former CFO’s embezzlement allegations, saying they were fabricated and part of a ploy to take control of the company. Ashley McDow, an attorney representing Scoobeez in its ongoing bankruptcy, said the company had nothing to add beyond what is in the public record.

As of late August, the company continues to recruit delivery drivers for locations throughout Southern California, Illinois, and Texas — and in court records, it has claimed that 99% of its revenue comes from Amazon. Newly filed personal injury lawsuits continue to roll in, and in May, Enterprise sued Scoobeez, claiming it owed it more than $700,000 for damages to vans it had leased the company.

Ohanessian and his wife are no longer with Scoobeez and lately have turned to another possible get-rich scheme: putting logistics on the blockchain.

In 2017, Courier Distribution Systems, another of Amazon’s larger delivery providers, was notified by Inc. magazine that it was one of the 500 fastest-growing privately held startups in the country. “Welcome,” the magazine’s editor-in-chief wrote in a congratulatory letter, “to the most exclusive club in business!”

Like other Amazon delivery companies, CDS — based outside of Atlanta but delivering Amazon packages in several states, including Wisconsin, California, Pennsylvania, and Illinois — was required to carry a full slate of insurance.

In addition to cargo, business, and general legal liability coverage, Amazon requires delivery firms to carry workers' compensation policies, which are designed to cover the costs of medical care for employees injured on the job as well as any lost wages.

But that system failed Aleasa Thomas, who worked for CDS in the Milwaukee area. In April 2017, while completing a delivery to a house, Thomas said, she was violently attacked by a dog, causing her to fall and hit her head.

Only later did Thomas discover that CDS — which had earned its place on the Inc. list by growing at least 10 times larger over the previous three years — had failed to pay its workers' compensation premiums in Wisconsin between February and June of 2017, meaning she was not covered. CDS was later hit with a $154,000 judgment for failing to pay workers' compensation insurance in the state.

Jim Blanchard, a CDS representative, acknowledged the four-month insurance lapse but said it occurred while the firm was applying for different coverage. He added that CDS paid all of Thomas’s “medical bills, all of her unpaid wages, and any other losses.”

Wisconsin was far from the only region where CDS appears to have fallen fell behind on its bills. The firm has faced at least two dozen lawsuits and other claims in recent years by employees who say it didn’t correctly pay them, fired them without cause, or discriminated against them. Some of those cases settled out of court. A tire company near San Diego won an $11,578 judgment against the company in November 2017 after CDS failed to pay its bills.

Elsewhere, CDS had faced a mutiny from some of its drivers. Jovon Bray, a dispatcher at CDS in Sacramento, said he was forced to quell a near riot in October 2015 when roughly 100 angry drivers showed up to work demanding to know why they hadn’t been properly paid. When Bray called a manager at headquarters for advice, he recalled being told, “You need to find a better lie to tell them.”

“The whole thing is like a joke. They had no rules established. I asked if there was a manual or a handbook, what are my expectations? They said, ‘You gotta create them as you go.’”

When it happened again two months later, Bray said he called again and declared that he wouldn’t work unless everyone — including himself — got paid on time. A few days later, he recalled receiving a phone call from a supervisor while at a holiday party. “You aren’t management material,” Bray recalled the person telling him before summarily firing him. Bray and several other workers sued CDS and eventually settled out of court.

“The whole thing is like a joke,” Bray told BuzzFeed News. “They had no rules established. I asked if there was a manual or a handbook, what are my expectations? They said, ‘You gotta create them as you go.’”

Blanchard denied the allegations. “I assume this has been fabricated,” he said. He added that “CDS has offered good-paying jobs and benefits to thousands of employees — many of whom lacked the education or skills to secure any other job paying as much as they earned at CDS — and largely without incident or dispute.”

In the wake of the uprising, CDS lost its Sacramento routes. But Amazon continues to work with the company in numerous other cities around the country.

The same labor problems that appear across Amazon’s delivery network were apparent at Inpax in the period leading up to the crash that killed Telesfora Escamilla. Just months after Amazon began working with the firm in 2015, it fell under investigation by the Department of Labor for chronically underpaying dozens of drivers and was ordered to pay employees back wages. The following year, regulators found Inpax had “willfully violated” labor laws a second time by failing to pay drivers overtime. Third and fourth investigations would uncover more violations and unpaid wages of more than $140,000.

CBS46 / Via cbs46.com Leonard Wright

Inpax’s founder and CEO, Leonard Wright, had a string of cocaine-related felony convictions and first registered the company shortly after finishing a three-year prison sentence for narcotics distribution. Yet despite the mounting warnings that Inpax had serious issues, Amazon kept shoveling more business in its direction. By 2016, the firm was delivering in at least five cities — Atlanta, Cincinnati, Miami, Dallas, and Chicago — Labor Department records acquired through the Freedom of Information Act show.

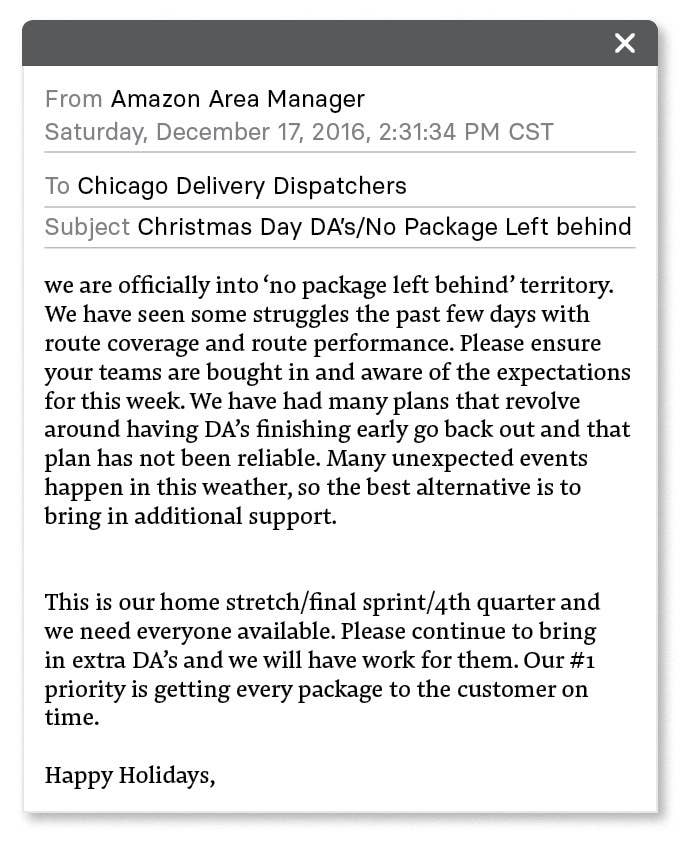

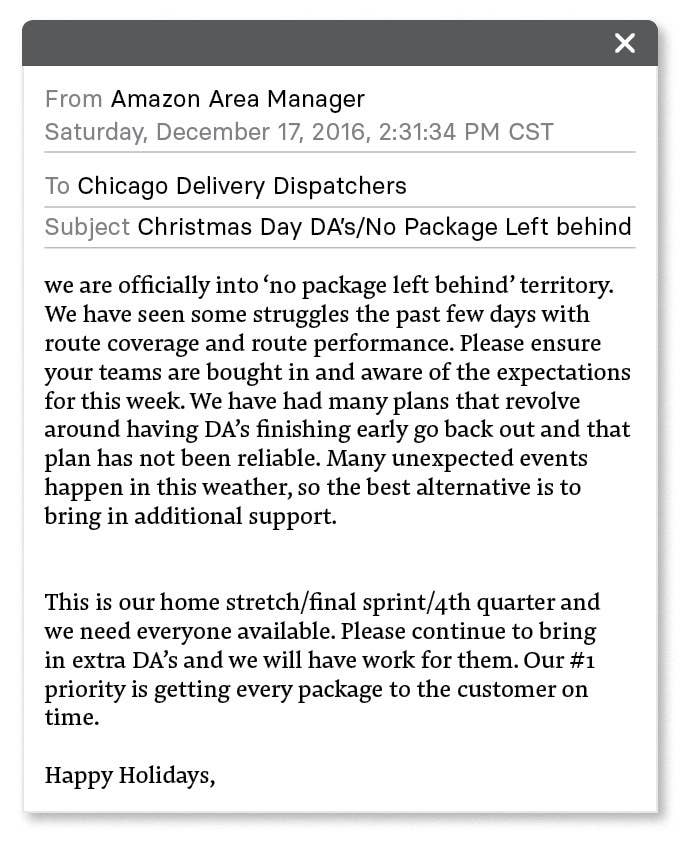

As Christmas of 2016 approached, Amazon was on track for what would be its biggest holiday season to date, ultimately shipping more than 1 billion packages worldwide. To handle the record-setting workload, it piled on the pressure, ramping up the number of packages each driver was expected to deliver each day.

Nurphoto / Getty Images

Amazon delivery vans are seen May 14 in Orlando.

When delivery drivers complain about the harsh conditions they face, Amazon refuses to admit any responsibility. But when a group of drivers banded together to advocate for their rights to fair pay and safe conditions, executives at the e-commerce giant moved quickly to quash any further such efforts.

In March 2017, a group of drivers for the delivery firm Silverstar Delivery met with a Teamsters organizer at a TGI Fridays outside of Detroit to complain about the shoddy condition of the vans they drove, Amazon GPS devices that conked out at crucial moments, and, in particular, a lack of overtime pay, despite shifts that routinely lasted as long as 12 hours.

The organizer convinced them to unionize, and the following month, Silverstar employees voted 22–7 to join the Teamsters, making it the only Amazon delivery contractor to have unionized to date.

Silverstar did not react positively to the news. Within weeks, drivers reported to the National Labor Relations Board that they were being fired for joining the union.

One of the workers claimed he was terminated in May after bringing back undelivered packages to the warehouse. When he complained, the worker said a manager told him, “I was told to write you up for anything because you joined the union,” according to NLRB filings.

The board dismissed the charges that workers were illegally fired in retaliation for unionizing, but allowed other claims of anti-union activity to proceed. Silverstar ultimately agreed to pay $15,696 to settle the matter.

The Teamsters named Amazon in their complaint, but the retailer denied having any legal relationship to the unionized workers. “While Amazon has a services contract with Silverstar, Amazon is not the employer of Silverstar’s employees,” the company wrote in a letter to the NLRB.

A few months later, Norm Collins, who had been elected shop steward, received a call from a Silverstar dispatcher who told him the company was shutting down its Michigan location immediately, putting dozens of drivers, as well as several dispatchers and managers, instantly out of work. “He said don’t report to work because Silverstar came down, packed up all their stuff, took the vans,” Collins recalled. “They’re gone.”

Not long after the successful unionization vote, a team of Amazon officials paid a visit to Chicago, where they gathered top management from delivery firms operating in the city at a hotel west of town, according to two people who attended the meeting. The topic: how to ensure that what happened to Silverstar would never happen to them.

“The whole purpose of the meeting was to say to you, ‘Here’s how to not get unionized. Because if you do, we pretty much don’t want anything to do with a union,’” said one attendee.

In July, a Canadian news site reported that Amazon had held a similar meeting to discourage organizing among drivers for Toronto-area delivery companies.

The closure of Silverstar hardly slowed down Amazon’s Detroit-area operations. Other delivery firms already operating in the area were happy to pick up the available routes.

Because of the low pay, long hours, and high stress of the job, turnover among Amazon delivery drivers is high.

Former dispatchers said it’s not uncommon for drivers to quit in the middle of their shifts, sometimes abandoning the vans on the road.

If a delivery firm doesn’t have enough drivers on any given day, it risks losing routes to competing delivery companies operating out of the same warehouse. Amazon routinely monitors and ranks the performance of each provider, delivery company managers say, and rewards its most reliable performers with additional and more profitable routes.

As a result, delivery firms are constantly recruiting drivers to get on the road as fast as possible — and in an economy with national unemployment currently below 4%, former managers described a perpetual hiring crisis that requires them to accept nearly anyone who walks through the door.

A manager at Sheard-Loman, for example, recently used Facebook to cast a wide net for potential drivers.

“I’m launching an AGGRESSIVE hiring campaign. If someone owes you money and they’re not working, if someone needs to move out yet using the excuse that they don’t have a job, if your baby’s daddy/momma is behind on child support, have them call me NOW,” he wrote. “I’m hiring on the SPOT.”

But despite the high pressure and tight margins, many companies have jumped at the opportunity to get a piece of Amazon’s home delivery business. Some have had their dreams crushed.

UPDATE

September 6, 2019, at 3:10 p.m.

This story was updated with an additional statement from Amazon.

Have you had experiences with Amazon or a company contracted by Amazon that you would like to share? To learn how to reach us securely, go to tips.buzzfeed.com. You can also email us at tips@buzzfeed.com.