March 3, 2020

Concerns over the spread of the novel coronavirus have translated into an economic slowdown. Stock markets have taken a hit: the UK’s FTSE 100 has seen its worst days of trading for many years and so have the Dow Jones and S&P in the US. Money has to go somewhere and the price of gold – seen as a stable commodity during extreme events – reached a seven-year high.

A look back at history can help us consider the economic effects of public health emergencies and how best to manage them. In doing so, however, it is important to remember that past pandemics were far more deadly than coronavirus, which has a relatively low death rate.

Without modern medicine and institutions like the World Health Organization, past populations were more vulnerable. It is estimated that the Justinian plague of 541 AD killed 25 million and the Spanish flu of 1918 around 50 million

By far the worst death rate in history was inflicted by the Black Death. Caused by several forms of plague, it lasted from 1348 to 1350, killing anywhere between 75 million and 200 million people worldwide and perhaps one half of the population of England. The economic consequences were also profound.

‘Anger, antagonism, creativity’

It might sound counter-factual – and this should not minimise the contemporary psychological and emotional turmoil caused by the Black Death – but the majority of those who survived went on to enjoy improved standards of living. Prior to the Black Death, England had suffered from severe overpopulation.

Following the pandemic, the shortage of manpower led to a rise in the daily wages of labourers, as they were able to market themselves to the highest bidder. The diets of labourers also improved and included more meat, fresh fish, white bread and ale. Although landlords struggled to find tenants for their lands, changes in forms of tenure improved estate incomes and reduced their demands.

But the period after the Black Death was, according to economic historian Christopher Dyer, a time of “agitation, excitement, anger, antagonism and creativity”. The government’s immediate response was to try to hold back the tide of supply-and-demand economics.

Concerns over the spread of the novel coronavirus have translated into an economic slowdown. Stock markets have taken a hit: the UK’s FTSE 100 has seen its worst days of trading for many years and so have the Dow Jones and S&P in the US. Money has to go somewhere and the price of gold – seen as a stable commodity during extreme events – reached a seven-year high.

A look back at history can help us consider the economic effects of public health emergencies and how best to manage them. In doing so, however, it is important to remember that past pandemics were far more deadly than coronavirus, which has a relatively low death rate.

Without modern medicine and institutions like the World Health Organization, past populations were more vulnerable. It is estimated that the Justinian plague of 541 AD killed 25 million and the Spanish flu of 1918 around 50 million

By far the worst death rate in history was inflicted by the Black Death. Caused by several forms of plague, it lasted from 1348 to 1350, killing anywhere between 75 million and 200 million people worldwide and perhaps one half of the population of England. The economic consequences were also profound.

‘Anger, antagonism, creativity’

It might sound counter-factual – and this should not minimise the contemporary psychological and emotional turmoil caused by the Black Death – but the majority of those who survived went on to enjoy improved standards of living. Prior to the Black Death, England had suffered from severe overpopulation.

Following the pandemic, the shortage of manpower led to a rise in the daily wages of labourers, as they were able to market themselves to the highest bidder. The diets of labourers also improved and included more meat, fresh fish, white bread and ale. Although landlords struggled to find tenants for their lands, changes in forms of tenure improved estate incomes and reduced their demands.

But the period after the Black Death was, according to economic historian Christopher Dyer, a time of “agitation, excitement, anger, antagonism and creativity”. The government’s immediate response was to try to hold back the tide of supply-and-demand economics.

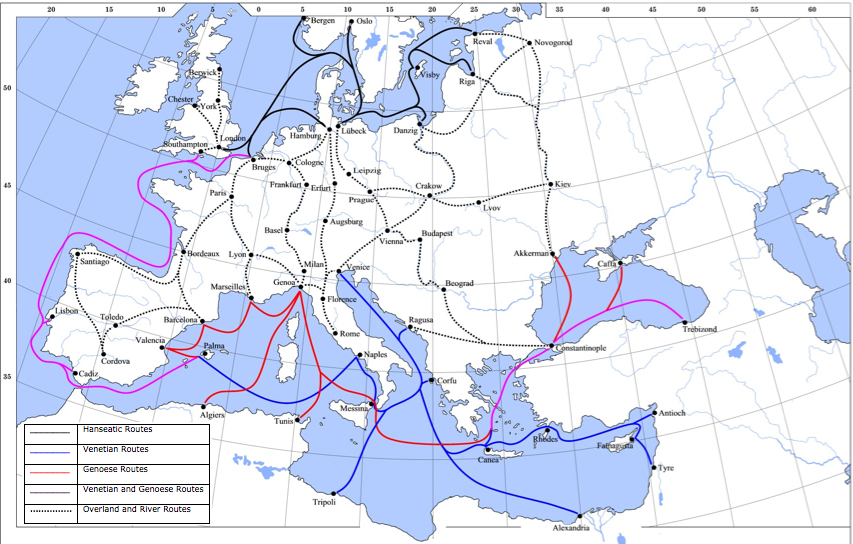

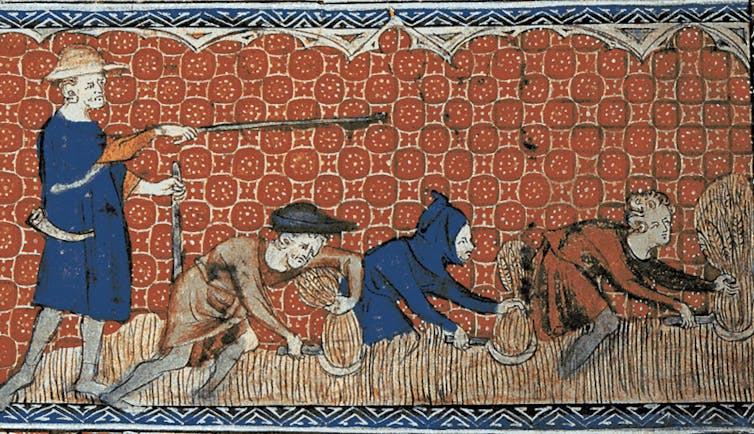

Life as a labourer in the 14th century was hard. British Library

This was the first time an English government had attempted to micromanage the economy. The Statute of Labourers law was passed in 1351 in an attempt to peg wages to pre-plague levels and restrict freedom of movement for labourers. Other laws were introduced attempting to control the price of food and even restrict which women were allowed to wear expensive fabrics.

But this attempt to regulate the market did not work. Enforcement of the labour legislation led to evasion and protests. In the longer term, real wages rose as the population level stagnated with recurrent outbreaks of the plague.

Landlords struggled to come to terms with the changes in the land market as a result of the loss in population. There was large-scale migration after the Black Death as people took advantage of opportunities to move to better land or pursue trade in the towns. Most landlords were forced to offer more attractive deals to ensure tenants farmed their lands.

A new middle class of men (almost always men) emerged. These were people who were not born into the landed gentry but were able to make enough surplus wealth to purchase plots of land. Recent research has shown that property ownership opened up to market speculation.

The dramatic population change wrought by the Black Death also led to an explosion in social mobility. Government attempts to restrict these developments followed and generated tension and resentment.

Meanwhile, England was still at war with France and required large armies for its campaigns overseas. This had to be paid for, and in England led to more taxes on a diminished population. The parliament of a young Richard II came up with the innovative idea of punitive poll taxes in 1377, 1379 and 1380, leading directly to social unrest in the form of the Peasants’ Revolt of 1381.

This was the first time an English government had attempted to micromanage the economy. The Statute of Labourers law was passed in 1351 in an attempt to peg wages to pre-plague levels and restrict freedom of movement for labourers. Other laws were introduced attempting to control the price of food and even restrict which women were allowed to wear expensive fabrics.

But this attempt to regulate the market did not work. Enforcement of the labour legislation led to evasion and protests. In the longer term, real wages rose as the population level stagnated with recurrent outbreaks of the plague.

Landlords struggled to come to terms with the changes in the land market as a result of the loss in population. There was large-scale migration after the Black Death as people took advantage of opportunities to move to better land or pursue trade in the towns. Most landlords were forced to offer more attractive deals to ensure tenants farmed their lands.

A new middle class of men (almost always men) emerged. These were people who were not born into the landed gentry but were able to make enough surplus wealth to purchase plots of land. Recent research has shown that property ownership opened up to market speculation.

The dramatic population change wrought by the Black Death also led to an explosion in social mobility. Government attempts to restrict these developments followed and generated tension and resentment.

Meanwhile, England was still at war with France and required large armies for its campaigns overseas. This had to be paid for, and in England led to more taxes on a diminished population. The parliament of a young Richard II came up with the innovative idea of punitive poll taxes in 1377, 1379 and 1380, leading directly to social unrest in the form of the Peasants’ Revolt of 1381.

Peasants revolting in 1381. Miniature by Jean de Wavrin

This revolt, the largest ever seen in England, came as a direct consequence of the recurring outbreaks of plague and government attempts to tighten control over the economy and pursue its international ambitions. The rebels claimed that they were too severely oppressed, that their lords “treated them as beasts”.

Lessons for today

While the plague that caused the Black Death was very different to the coronavirus that is spreading today, there are some important lessons here for future economic growth. First, governments must take great care to manage the economic fallout. Maintaining the status quo for vested interests can spark unrest and political volatility.

Second, restricting freedom of movement can cause a violent reaction. How far will our modern, mobile society consent to quarantine, even when it is for the greater good?

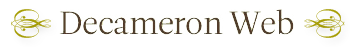

Plus, we should not underestimate the knee-jerk, psychological reaction. The Black Death saw an increase in xenophobic and antisemitic attacks. Fear and suspicion of non-natives changed trading patterns.

There will be winners and losers economically as the current public health emergency plays out. In the context of the Black Death, elites attempted to entrench their power, but population change in the long term forced some rebalancing to the benefit of labourers, both in terms of wages and mobility and in opening up the market for land (the major source of wealth at the time) to new investors. Population decline also encouraged immigration, albeit to take up low skilled or low-paid jobs. All are lessons that reinforce the need for measured, carefully researched responses from current governments.

This revolt, the largest ever seen in England, came as a direct consequence of the recurring outbreaks of plague and government attempts to tighten control over the economy and pursue its international ambitions. The rebels claimed that they were too severely oppressed, that their lords “treated them as beasts”.

Lessons for today

While the plague that caused the Black Death was very different to the coronavirus that is spreading today, there are some important lessons here for future economic growth. First, governments must take great care to manage the economic fallout. Maintaining the status quo for vested interests can spark unrest and political volatility.

Second, restricting freedom of movement can cause a violent reaction. How far will our modern, mobile society consent to quarantine, even when it is for the greater good?

Plus, we should not underestimate the knee-jerk, psychological reaction. The Black Death saw an increase in xenophobic and antisemitic attacks. Fear and suspicion of non-natives changed trading patterns.

There will be winners and losers economically as the current public health emergency plays out. In the context of the Black Death, elites attempted to entrench their power, but population change in the long term forced some rebalancing to the benefit of labourers, both in terms of wages and mobility and in opening up the market for land (the major source of wealth at the time) to new investors. Population decline also encouraged immigration, albeit to take up low skilled or low-paid jobs. All are lessons that reinforce the need for measured, carefully researched responses from current governments.

Adrian R. Bell

Chair in the History of Finance and Research Dean, Prosperity and Resilience, Henley Business School, University of Reading

Chair in the History of Finance and Research Dean, Prosperity and Resilience, Henley Business School, University of Reading

University of Reading provide funding as members of The Conversation UK.

View all partners

We believe in the free flow of information

Republish our articles for free, online or in print, under Creative Commons licence.Republish this article

View all partners

We believe in the free flow of information

Republish our articles for free, online or in print, under Creative Commons licence.Republish this article