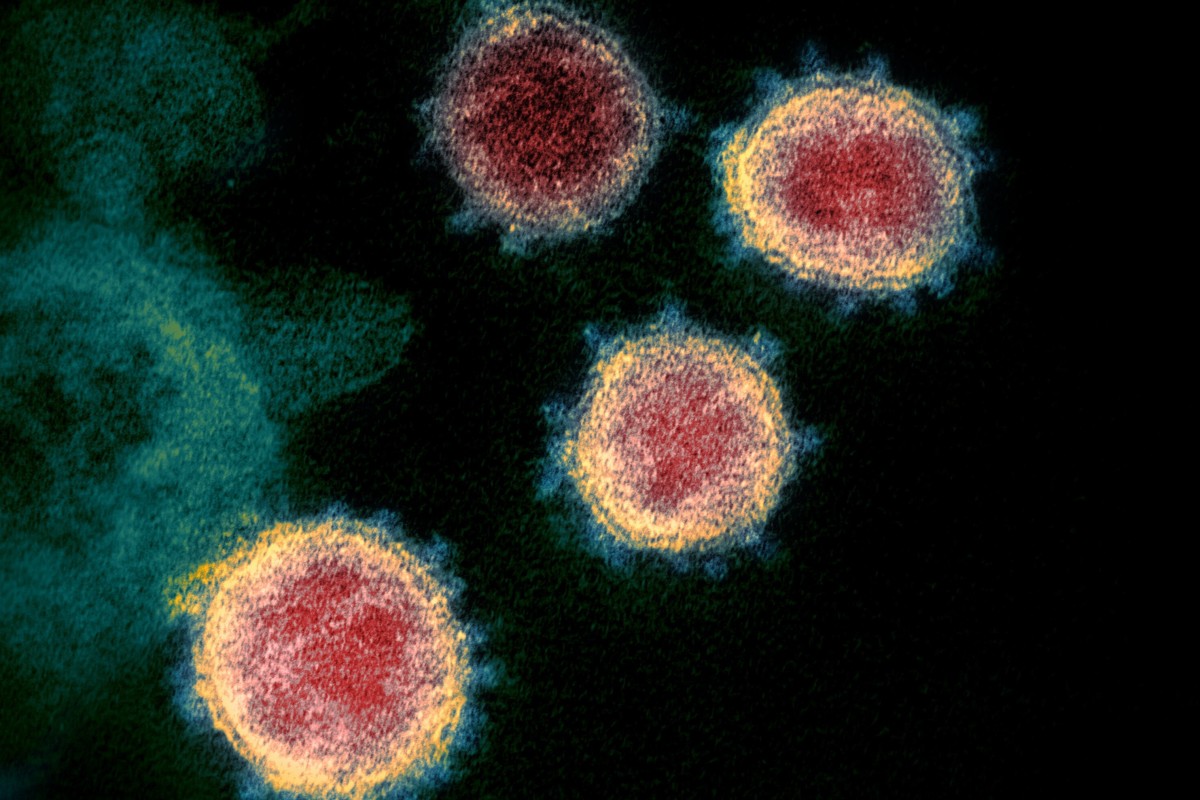

Scientists concluded early the virus could be devastating, but for more than two months they did not clearly signal their worsening fears to the government

Boris Johnson, who himself has been sickened by Covid-19, has been criticised for not moving swiftly to organise mass tests and mobilise ventilator supplies

Reuters Published: 10 Apr, 2020

British Prime Minister Boris Johnson. Photo: AFP

HOW TO WASH YOUR HANDS

It was early spring when British scientists laid out the bald truth to their government. It was “highly likely”, they said, that there was now “sustained transmission” of Covid-19 in the United Kingdom.

If unconstrained and if the virus behaved as in China, up to four-fifths of Britons could be infected and one in a hundred might die, wrote the scientists, members of an official committee set up to model the spread of pandemic flu, on March 2. Their assessment did not spell it out, but that was a prediction of over 500,000 deaths in this nation of nearly 70 million.

It was early spring when British scientists laid out the bald truth to their government. It was “highly likely”, they said, that there was now “sustained transmission” of Covid-19 in the United Kingdom.

If unconstrained and if the virus behaved as in China, up to four-fifths of Britons could be infected and one in a hundred might die, wrote the scientists, members of an official committee set up to model the spread of pandemic flu, on March 2. Their assessment did not spell it out, but that was a prediction of over 500,000 deaths in this nation of nearly 70 million.

Yet the next day, March 3, Prime Minister Boris Johnson was his cheery self. He joked that he was still shaking hands with everyone, including at a hospital treating coronavirus patients.

“Our country remains extremely well prepared,” Johnson said as Italy reached 79 deaths. “We already have a fantastic NHS,” the national public health service, “fantastic testing systems and fantastic surveillance of the spread of disease.”

Alongside him at the Downing Street press conference was Chris Whitty, the government’s chief medical adviser and himself an epidemiologist. Whitty passed on the modelling committee’s broad conclusions, including the prediction of a possible 80 per cent infection rate and the consequent deaths.

But he played them down, saying the number of people who would be infected was probably “a lot lower” and coming up with a total was “largely speculative”.

The upbeat tone of that briefing stood in sharp contrast with the growing unease of many of the government’s scientific advisers behind the scenes. They were already convinced that Britain was on the brink of a disastrous outbreak, a Reuters investigation has found.

Interviews with more than 20 British scientists, key officials and senior sources in Johnson’s Conservative Party, and a study of minutes of advisory committee meetings and public testimony and documents, show how these scientific advisers concluded early the virus could be devastating.

But the interviews and documents also reveal that for more than two months, the scientists whose advice guided Downing Street did not clearly signal their worsening fears to the public or the government. Until March 12, the risk level, set by the government’s top medical advisers on the recommendation of the scientists, remained at “moderate”, suggesting only the possibility of a wider outbreak.

“You know, there’s a small little cadre of people in the middle, who absolutely did realise what was going on, and likely to happen,” said John Edmunds, a professor of infectious disease modelling and a key adviser to the government, known for his work on tracking

Ebola. Edmunds was among those who did call on the government to elevate the warning level earlier.

From the outset, said Edmunds, work by scientists had shown that, with only limited interventions, the virus would trigger an “overwhelming epidemic” in which

Britain’s health service was not going “to get anywhere near being able to cope with it. That was clear from the beginning.”

But he said: “I do think there’s a bit of a worry in terms you don’t want to unnecessarily panic people.”

But the interviews and documents also reveal that for more than two months, the scientists whose advice guided Downing Street did not clearly signal their worsening fears to the public or the government. Until March 12, the risk level, set by the government’s top medical advisers on the recommendation of the scientists, remained at “moderate”, suggesting only the possibility of a wider outbreak.

“You know, there’s a small little cadre of people in the middle, who absolutely did realise what was going on, and likely to happen,” said John Edmunds, a professor of infectious disease modelling and a key adviser to the government, known for his work on tracking

Ebola. Edmunds was among those who did call on the government to elevate the warning level earlier.

From the outset, said Edmunds, work by scientists had shown that, with only limited interventions, the virus would trigger an “overwhelming epidemic” in which

Britain’s health service was not going “to get anywhere near being able to cope with it. That was clear from the beginning.”

But he said: “I do think there’s a bit of a worry in terms you don’t want to unnecessarily panic people.”

Johnson, who himself has sickened with the virus, moved more slowly than the leaders of many other prosperous countries to adopt a lockdown. He has been criticised for not moving more swiftly to organise mass tests and mobilise supplies of life-saving equipment and beds. Johnson was hospitalised on April 5 and moved to intensive care the next day.

It is too soon to judge the ultimate soundness of Britain’s early response. If history concludes that it was lacking, then the criticism levelled at the prime minister may be that, rather than ignoring the advice of his scientific advisers, he failed to question their assumptions.

Interviews and records published so far suggest that the scientific committees that advised Johnson did not study, until mid-March, the option of the kind of stringent lockdown adopted early on in China, where the disease arose in December, and then followed by much of Europe and finally by Britain itself. The scientists’ reasoning: Britons, many of them assumed, simply wouldn’t accept such restrictions.

The British scientists were also mostly convinced – and many still are – that, once the new virus escaped China, quarantine measures would likely not succeed. Minutes of technical committees reviewed by Reuters indicate that almost no attention was paid to preparing a programme of mass testing.

Other minutes and interviews show Britain was following closely a well-laid plan to fight a flu pandemic – not this deadlier disease. The scientists involved, however, deny that the flu focus ultimately made much difference.

Now, as countries debate how to combat the virus, some experts here say, the lesson from the British experience may be that governments and scientists worldwide must increase the transparency of their planning so that their thinking and assumptions are open to challenge.

John Ashton, a clinician and former regional director of Public Health England, the government agency overseeing health care, said the government’s advisers took too narrow a view and hewed to limited assumptions.

They were too “narrowly drawn as scientists from a few institutions”, he said. Their handling of Covid-19, Ashton said, shows the need for a broader approach. “In the future we need a much wider group of independent advisers.”

Michael Cates, who succeeded Stephen Hawking as Lucasian Professor of Mathematics at Cambridge University, is leading an initiative by the Royal Society, Britain’s leading scientific body, to bring modellers in from other scientific disciplines to help understand the epidemic.

“Without faulting anyone so far, it’s vital, where there is such a lot at stake, to throw the maximum possible light on the methods, assumptions and data built into our understanding of how this epidemic will develop,” he said.

A spokesperson for the Department of Health and Social Care said in a statement that the government was delivering “a science-led action plan” to contain the outbreak. “As the public would expect, we regularly test our pandemic plans and what we learned from previous exercises has helped us to rapidly respond to Covid-19.”

A low risk to the public

When news came from China in January of a new infectious disease, Johnson had reason to believe his country was well prepared. It had some of the world’s best scientists and a well-drilled plan to deal with potentially lethal pandemics. Perhaps, some scientists say in hindsight, the plan made them slow to adapt.

For many years, the Cabinet Office – a collection of officials who act as the prime minister’s direct arm to run the government – took the threat of pandemics seriously. Presciently, it rated pandemics as the No 1 threat to the country, ahead of terrorism and financial crashes.

At the centre of planning was a small group of scientists, among them Edmunds. His research group at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine runs one of the two computer modelling centres for epidemics that have mostly driven government policy. The other is at nearby Imperial College. Edmunds remembers that early in the outbreak, the data from China were sketchy, in the period “where the Chinese were trying to pretend that this wasn’t transmissible between humans”.

Edmunds and his colleague at Imperial, Neil Ferguson, were part of an alphabet soup of committees that fed advice into the Cabinet Office machinery around the prime minister. Both were founders of the flu pandemic modelling committee, known as SPI-M, that produced the March 2 report warning of more than 500,000 deaths. This committee had met together for nearly 15 years.

Ferguson did not respond to a request to be interviewed for this article.

Coronavirus: Decoding Covid-19

Edmunds and Ferguson were also part of NERVTAG, the New and Emerging Respiratory Virus Threats Advisory Group. Both too were members of the Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies, known as SAGE, that advises the government in times of crisis. SAGE reports directly to Johnson and the government’s main emergency committee, COBRA.

At first, when NERVTAG met on January 13, it studied information from China that there was “no evidence of significant human to human transmission” of the new virus, according to minutes of the meeting. The scientists agreed the risk to the UK population was “very low”.

The evidence soon changed, but this wasn’t reflected in the official threat level. By the end of January, scientists in China began releasing clinical data. Case studies published in the British medical journal, The Lancet, showed 17 per cent of the first 99 coronavirus cases needed critical care. Eleven patients died. Another Chinese study, in the same publication, warned starkly of a global spread and urged: “Preparedness plans and mitigation interventions should be readied for quick deployment globally.”

Edmunds recalled that “from about mid-January onwards, it was absolutely obvious that this was serious, very serious”. Graham Medley, a professor of infectious diseases modelling at the London School and chairman of SPI-M, agreed. He said that the committee was “clear that this was going to be big from the first meeting”. At the end of January, his committee moved into “wartime” mode, he said, reporting directly into SAGE.

Dr Jon Read, a senior lecturer in biostatistics at the University of Lancaster, also a member of SPI-M, said by the end of January it was apparent the virus had “pandemic potential” and that death rates for the elderly were brutal. “From my perspective within the sort of modelling community, everybody’s aware of this, and we’re saying that this is probably going to be pretty bad,” he said.

But the scientists did not articulate their fears forcefully to the government, minutes of committee meetings reveal.

A spokesperson for the Department of Health and Social Care said in a statement that the government was delivering “a science-led action plan” to contain the outbreak. “As the public would expect, we regularly test our pandemic plans and what we learned from previous exercises has helped us to rapidly respond to Covid-19.”

A low risk to the public

When news came from China in January of a new infectious disease, Johnson had reason to believe his country was well prepared. It had some of the world’s best scientists and a well-drilled plan to deal with potentially lethal pandemics. Perhaps, some scientists say in hindsight, the plan made them slow to adapt.

For many years, the Cabinet Office – a collection of officials who act as the prime minister’s direct arm to run the government – took the threat of pandemics seriously. Presciently, it rated pandemics as the No 1 threat to the country, ahead of terrorism and financial crashes.

At the centre of planning was a small group of scientists, among them Edmunds. His research group at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine runs one of the two computer modelling centres for epidemics that have mostly driven government policy. The other is at nearby Imperial College. Edmunds remembers that early in the outbreak, the data from China were sketchy, in the period “where the Chinese were trying to pretend that this wasn’t transmissible between humans”.

Edmunds and his colleague at Imperial, Neil Ferguson, were part of an alphabet soup of committees that fed advice into the Cabinet Office machinery around the prime minister. Both were founders of the flu pandemic modelling committee, known as SPI-M, that produced the March 2 report warning of more than 500,000 deaths. This committee had met together for nearly 15 years.

Ferguson did not respond to a request to be interviewed for this article.

Coronavirus: Decoding Covid-19

Edmunds and Ferguson were also part of NERVTAG, the New and Emerging Respiratory Virus Threats Advisory Group. Both too were members of the Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies, known as SAGE, that advises the government in times of crisis. SAGE reports directly to Johnson and the government’s main emergency committee, COBRA.

At first, when NERVTAG met on January 13, it studied information from China that there was “no evidence of significant human to human transmission” of the new virus, according to minutes of the meeting. The scientists agreed the risk to the UK population was “very low”.

The evidence soon changed, but this wasn’t reflected in the official threat level. By the end of January, scientists in China began releasing clinical data. Case studies published in the British medical journal, The Lancet, showed 17 per cent of the first 99 coronavirus cases needed critical care. Eleven patients died. Another Chinese study, in the same publication, warned starkly of a global spread and urged: “Preparedness plans and mitigation interventions should be readied for quick deployment globally.”

Edmunds recalled that “from about mid-January onwards, it was absolutely obvious that this was serious, very serious”. Graham Medley, a professor of infectious diseases modelling at the London School and chairman of SPI-M, agreed. He said that the committee was “clear that this was going to be big from the first meeting”. At the end of January, his committee moved into “wartime” mode, he said, reporting directly into SAGE.

Dr Jon Read, a senior lecturer in biostatistics at the University of Lancaster, also a member of SPI-M, said by the end of January it was apparent the virus had “pandemic potential” and that death rates for the elderly were brutal. “From my perspective within the sort of modelling community, everybody’s aware of this, and we’re saying that this is probably going to be pretty bad,” he said.

But the scientists did not articulate their fears forcefully to the government, minutes of committee meetings reveal.

On January 21, scientists on NERVTAG endorsed the elevation of the British risk warning from Covid-19 from “very low” to “low”. SAGE met formally for the first time the following day about the coronavirus threat. So did COBRA, which was chaired by

Matt Hancock, the health secretary, who would contract the virus himself in late March. He told reporters after the meeting: “The clinical advice is that the risk to the public remains low.”

In response to questions from Reuters, the government’s Department of Health declined to clarify how the risk levels are defined or what action, if any, they trigger. In a statement, a spokesperson said: “Increasing the risk level in the UK is a belt and braces measure which allows the government to plan for all future eventualities.”

Two days later, China put the city of Wuhan, where the outbreak began, into a complete lockdown. Hubei, the surrounding province, would follow. But already, 17 passenger flights had flown directly from Wuhan to Britain since the start of 2020, and 614 flights from the whole of China, according to FlightRadar24, a flight-tracking service. That meant thousands of Chinese, some of them potential carriers, had come to Britain. On April 5, scientific adviser Ferguson said he estimated only one-third of infected people reaching Britain had been detected.

As they watched China impose its lockdown, the British scientists assumed that such drastic actions would never be acceptable in a democracy like the UK. Among those modelling the outbreak, such stringent countermeasures were not, at first, examined.

“We had milder interventions in place,” said Edmunds, because no one thought it would be acceptable politically “to shut the country down”. He added: “We did not model it because it did not seem to be on the agenda. And Imperial (College) did not look at it either.” The NERVTAG committee agreed, noting in its minutes that tough measures in the short-term would be pointless, as they “would only delay the UK outbreak, not prevent it”.

That limited approach mirrored Britain’s long-standing pandemic flu strategy. The Department of Health declined a request from Reuters for a copy of its updated pandemic plan, without providing a reason.

But a copy of the 2011 “UK Influenza Pandemic Preparedness Strategy 2011”, which a spokesman said was still relevant, stated the “working presumption will be that government will not impose any such restrictions.

The emphasis will instead be on encouraging all those who have symptoms to follow the advice to stay at home and avoid spreading their illness”.

Medical staff during a break in the grounds of St Thomas’ Hospital

in London, where British Prime Minister Boris Johnson is

undergoing treatment. Photo: Reuters

According to one senior Conservative Party politician, who was officially briefed as the crisis unfolded, the close involvement in the response to the coronavirus of the same scientific advisers and civil servants who drew up the flu plan may have created a “cognitive bias”.

“We had in our minds that Covid-19 was a nasty flu and needed to be treated as such,” he said. “The implication was it was a disease that could not be stopped and that it was ultimately not that deadly.”

According to one senior Conservative Party politician, who was officially briefed as the crisis unfolded, the close involvement in the response to the coronavirus of the same scientific advisers and civil servants who drew up the flu plan may have created a “cognitive bias”.

“We had in our minds that Covid-19 was a nasty flu and needed to be treated as such,” he said. “The implication was it was a disease that could not be stopped and that it was ultimately not that deadly.”

While Britain was prepared to fight the flu, places in Asia like China, Hong Kong,

Singapore and South Korea had built their pandemic plans with lessons learned from fighting the more lethal Sars outbreak that began in 2002, he said. SARS had a fatality rate of up to 14 per cent. As a result, these countries, he said, were more ready to resort to widespread testing, lockdowns and other draconian measures to keep their citizens from spreading the virus.

Scientists involved in the British response disagree that following the government’s flu plan clouded their thinking or influenced the outbreak’s course. The plan had a “reasonable worst case” scenario as devastating as the worst predictions for Covid-19, they note.

Mark Woolhouse, a professor of infectious diseases epidemiology at the University of Edinburgh, and a member of the SPI-M committee, said Covid-19 did behave differently than an expected pandemic flu – for example school closures proved to be far less effective in slowing the spread of the coronavirus. But, broadly, “the government has been consistently responsive to changing facts”.

By the end of January, the government’s chief medical adviser, Whitty, was explaining to politicians in private, according to at least two people who spoke to him, that if the virus escaped China, it would in time infect the great majority of people in Britain. It could only be slowed down, not stopped. On January 30, the government raised the threat level to “moderate” from “low”.

The country’s medical officers “consider it prudent for our governments to escalate planning and preparation in case of a more widespread outbreak”, a statement said at the time. Whitty did not respond to questions from Reuters for this article.

A time to prepare

On the evening of January 31, Johnson sat before a fireplace in 10 Downing Street and told the nation, in a televised address: “This is the moment when the dawn breaks and the curtain goes up on a new act in our great national drama.”

He was talking of finally delivering Brexit, or what he called “this recaptured sovereignty”. Until that moment, Johnson’s premiership had been utterly absorbed by delivering on that challenge.

With Brexit done, Johnson had the chance to focus on other matters the following month, among them the emerging virus threat. But leaving the European Union had a consequence.

Between February 13 and March 30, Britain missed a total of eight conference calls or meetings about the coronavirus between EU heads of state or health ministers – meetings that Britain was still entitled to join. Although Britain did later make an arrangement to attend lower-level meetings of officials, it had missed a deadline to participate in a common purchase scheme for ventilators, to which it was invited.

Ventilators, vitally important to treating the direst cases of Covid-19, have fallen into short supply globally. Johnson’s spokesman blamed an administrative error.

A Downing Street aide said that from around the end of January, Johnson concentrated his attention increasingly on the coronavirus threat, receiving “very frequent” updates at least once per day from mid February, either in person or via a daily dashboard of cases.

In the medical and scientific world, there was growing concern about the threat of the virus to Britain. A report from Exeter University, published on February 12, warned a British outbreak could peak within four months and, without mitigation, infect 45 million people.

That worried Rahuldeb Sarkar, a consultant doctor in respiratory medicine and critical care in the county of Kent, who foresaw that intensive care beds could be swamped. Even if disease transmission was reduced by half, he wrote in a report aimed at clinicians and actuaries in mid-February, a coronavirus outbreak in Britain would “have a chance of overwhelming the system”.

With Whitty stating in a BBC interview on February 13 that a British outbreak was still an “if, not a when”. Richard Horton, a medical doctor and editor of The Lancet, said the government and public health service wasted an opportunity that month to prepare quarantine restriction measures and a programme of mass tests, and procure resources like ventilators and personal protective equipment for expanded intensive care.

Calling the lost chance a “national scandal” in a later editorial, he would testify to parliament about a mismatch between “the urgent warning that was coming from the frontline in China” and the “somewhat pedestrian evaluation” of the threat from the scientific advice to the government.

After developing a test for the new virus by January 10, health officials adopted a centralised approach to its deployment, initially assigning a single public laboratory in north London to perform the tests. But, according to later government statements, there was no wider plan envisaged to make use of hundreds of laboratories across the country, both public and private, that could have been recruited.

According to emails and more than a dozen scientists interviewed by Reuters, the government issued no requests to labs for help with staff or testing equipment until the middle of March, when many abruptly received requests to hand over nucleic acid extraction instruments, used in testing. An executive at the Weatherall Institute of Molecular Medicine at the University of Oxford said he could have carried out up to 1,000 tests per day from February. But the call never came.

“You would have thought that they would be bashing down the door,” said the executive, who spoke on condition of anonymity. By April 5, Britain had carried out 195,524 tests, in contrast to at least 918,000 completed a week earlier in Germany.

Nor was there an effective effort to expand the supply of ventilators. The Department of Health said in a statement that the government started talking to manufacturers of ventilators about procuring extra supplies in February. But it was not until March 16, after it was clear supplies could run out, that Johnson launched an appeal to industry to help ramp up production.

Charles Bellm, managing director of Intersurgical, a global supplier of medical ventilation products based outside London, said he has been contacted by more than a dozen governments around the world, including

France, New Zealand and Indonesia. But there had been no contact from the British government. “I find it somewhat surprising, I have spoken to a lot of other governments,” he said.

Countering such criticism, Hancock, the health minister, said the government is on track to deliver about 10,000 more ventilators in the coming weeks. One reason Britain was behind some countries on testing, he said, was the absence of a large diagnostics industry at the outbreak of the epidemic. “We did not have the scale.”

Game over

It was during the school half-term holidays in February that frontline doctor Nicky Longley began to realise that early efforts to contain the disease were likely doomed.

For weeks now, doctors and public health workers had been watching out for people with flu-like symptoms coming in from China. Longley, an infectious diseases consultant at London’s Hospital for Tropical Diseases, was part of a team that staffed a public health service helpline for those with symptoms. The plan, she said, had been to make all effort to catch every case and their contacts. And “to start with, it looked like it was working”.

But then, bad news. First, on Wednesday February 19, came the shock news from Iran of two deaths. Then, on Friday the 21st, came a death in Italy and a bloom of cases in Lombardy and Veneto regions. Britain has close links to both countries. Thousands of Britons were holidaying in

Italy that week.

“I don’t think anybody really foresaw what was happening in Italy,” Longley said. “And I think, the minute everybody saw that, we thought: ‘This is game over now’.”

Why Europe’s hospitals – among world’s best – are struggling with virus

1 Apr 2020

Until then, Longley said, everyone felt “there was a chance to stamp it out” even though most were sceptical it could be done long-term. But after

Iran and Italy, it was obvious containment would not work.

The contact tracing continued for a while. But as the cases in London built up, and the volume of calls to the helpline mushroomed, the priority began to shift to clinical care of the serious cases. “At a certain point you have to make a decision about where you put your efforts as a workforce.”

Edmunds noted that Iran and Italy had hardly reported a case until that point. “And then, all of sudden you had deaths recorded.” There was a rule of thumb that, in an outbreak’s early stages, for each death there were probably 1,000 cases in a community. “And so it was quite clear that there were at least thousands of cases in Italy, possibly tens of thousands of cases in Italy right then.”

Amid the dreadful news from Italy, the scientists at NERVTAG convened by phone on that Friday, February 21. But they decided to recommend keeping the threat level at “moderate”, where it had sat since January 30.

The minutes don’t give a detailed explanation of the decision. Edmunds, who had technical difficulties and could not be heard on the call, emailed afterwards to ask the warning to be elevated to “high”, the minutes revealed. But the warning level remained lower. It’s unclear why.

“I just thought, are we still, we still thinking that it’s mild or something? It definitely isn’t, you know,” said Edmunds.

A spokesman for the government’s chief scientific adviser, Sir Patrick Vallance, did not directly respond to Reuters questions about the threat level. Asked whether, with hindsight, the scientists’ approach was the right one, the spokesperson said in a statement that “SAGE and advisers provide advice, while ministers and the government make decisions”.

Herd Immunity

On Sunday, March 1, Ferguson, Edmunds and other advisers spent the day with NHS public health service experts trying to work out how many hospital beds and other key resources would be needed as the outbreak exploded. By now, Italian data was showing that a tenth of all infected patients needed intensive care.

The following day, pandemic modelling committee SPI-M produced its “consensus report” that warned the coronavirus was now transmitting freely in Britain. That Thursday, March 5, the first death in Britain was announced. Italy, which reached 827 deaths by March 11, ordered a national lockdown. Spain and France prepared to follow suit.

Johnson held out against stringent measures, saying he was following the advice of the government’s scientists. He asserted on March 9: “We are doing everything we can to combat this outbreak, based on the very latest scientific and medical advice.”

Indeed, the government’s Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies, SAGE, had recommended that day, with no dissension recorded in its summary, that Britain reject a China-style lockdown. SAGE decided that “implementing a subset of measures would be ideal”, according to a record of its conclusions. Tougher measures could create a “large second epidemic wave once the measures were lifted”, SAGE said.

On March 12 came a bombshell for the British public. Whitty, the chief medical officer, announced Britain had moved the threat to British citizens from “moderate” to “high”. And he said the country had moved from trying to contain the disease to trying to slow its spread. New cases were not going to be tracked at all.

“It is no longer necessary for us to identify every case,” he said. Only hospital cases would, in future, be tested for the virus. What had been an undisclosed policy was in the open: beyond a certain point, attempts to completely extinguish the virus would stop.

The same day, putting aside his jokey self, Johnson made a speech in Downing Street, flanked by two Union Jacks and evoking the spirit of Winston Churchill’s “darkest hour” address. He warned: “I must level with you, level with the British public – more families, many more families are going to lose loved ones before their time.”

For most Britons, it came as a shock. Several of the next day’s newspapers splashed Johnson’s words on their front pages.

Vallance, the government’s chief scientific adviser, who chaired SAGE, said in a BBC interview on March 13 that the plan was to simply control the pace of infection. The government had, for now, rejected what he called “eye-catching measures” like stopping mass gatherings such as football games or closing schools.

The “aim is to try and reduce the peak, broaden the peak, not to suppress it completely”. Most people would get the virus mildly, and this would build up “herd immunity” which, in time, would stop the disease’s progress.

But by now, the country was rebelling. Major institutions decided to close. After players began to get infected, the professional football leagues suspended their games. As Johnson still refused to close schools and ban mass gatherings, the Daily Mirror’s banner headline, summing up a widespread feeling, asked on March 13: “Is It Enough?”

The catalyst for a policy reversal came on March 16 with the publication of a report by Neil Ferguson’s Imperial College team. It predicted that, unconstrained, the virus could kill 510,000 people. Even the government’s “mitigation” approach could lead to 250,000 deaths and intensive care units being overwhelmed at least eight times over.

Imperial’s prediction of over half a million deaths was no different from the report by the government’s own pandemic modelling committee two weeks earlier.

Yet it helped trigger a policy turnaround, both in London and in Washington, culminating seven days later in Johnson announcing a full lockdown of Britain. The report also jarred the US administration into tougher measures to slow the virus’ spread.

Ferguson was now in isolation himself after catching the virus. Testifying by video link to a committee in Parliament, he explained why he and other scientific advisers had shifted from advocating partial social-distancing measures to warning that without a rigorous shutdown, the NHS would be overwhelmed. The reason, he said, lay in data coming out of Italy that showed large numbers of patients required critical care.

“The revision was that, basically, estimates of the proportion of patients requiring invasive ventilation, mechanical ventilation, which is only done in a critical care unit, roughly doubled,” he said.

Edmunds had a different explanation for the policy shift.

What allowed Britain to alter course, said Edmunds, was a lockdown in Italy that “opened up the policy space” coupled with new data. First came a paper by Edmunds’ own London School team that examined intermittent lockdowns, sent to the modelling committee on March 11 and validated by Edinburgh University. Ferguson’s revised Imperial research followed.

Woolhouse, the Edinburgh professor, confirmed the sequence.

Edmunds said these new studies together had demonstrated that if the British government imposed a lengthy period of tougher measures, perhaps relaxed periodically, then the size of the epidemic could be substantially reduced.

Still, without a vaccine or effective treatments, it’s going to be hard to avoid a substantial part of the British population getting infected, said Edmunds. “Until you get to a vaccine, there is no way of getting out of this without certainly tens of thousands of deaths,” he said. “And probably more than that.”

Now subject to intense public scrutiny, the modelling teams at universities across Britain continue to work on different scenarios for how the world can escape the virus’s clutches. According to Medley, the chairman of the SPI-M pandemic modelling committee, no one now doubts, for all the initial reservations, that a lockdown was essential in Britain.

Medley added: “At the moment we don’t know what’s going to happen in six months. All we know is that unless we stop transmission now, the health service will collapse. Yep, that’s the only thing we know for sure.”

---30---