Arrests of US journalists halfway through 2020 outnumber similar arrests in China in 2019

Alex WoodwardNew York The Independent JULY 9,2020

At least 50 journalists in the US have been arrested during Black Lives Matter demonstrations across the US, while dozens of others have also been injured by rubber bullets, pepper spray and tear gas.

The US Press Freedom Tracker has collected more than 500 incidents from 382 reports, from the unrest in Minneapolis in the wake of George Floyd‘s killing by police in late May, to demonstrations in more than 70 cities across 35 states since.

At least 46 journalists were arrested between the end of May and the beginning of June, according to data collected by the organisation. Dozens of others reported injuries from law enforcement, firing “less lethal” projectiles, tear gas canisters and other weapons into crowds or directly at reporters during demonstrations, even when they had identified themselves and shown credentials, the organisation reports.

Two reporters have suffered permanent eye injuries.

The latest reports mark a significant spike since the end of May, when nationwide protests started, at which point the organisation had recorded only five arrests and 26 attacks for the entire year by that point.

Read more

Attacks on American journalists have become severe and dangerous

Trump said journalists ‘should be executed’, ex-aide Bolton claims

But by the end of the month, the number of attacks had increased nearly five times, after more than a month of nightly protests, vigils and other demonstrations against police violence and racial injustice.

“The importance of documenting these – and doing it as quickly as we can – is not lost: the conversations and reckoning that lie ahead of us as a country are taking shape right now,” Press Freedom Tracker managing editor Kristin McCudden said in a statement.

“No matter where we’re talking about it, the message is the same: what’s happened in 70 cities in more than 30 states across the nation in one month is unlike anything we’ve seen in modern history and surpasses the Tracker’s entire three-year history of documentation.”

Minneapolis has had 71 reported incidents against reporters, followed by Washington DC with 33, New York with 27, and Los Angeles with 20, the Press Freedom Tracker reports.

By the Fourth of July weekend, demonstrations had been going for more than 40 days, from memorials and rallies for victims of police violence to groups of people attempting to dislodge monuments to Confederates and slaveholders, including prominent US figures and former presidents.

Reporters used social media to capture several of these incidents, while news networks were devoting significant live coverage to protests in the first weeks of demonstrations and finding themselves targets.

CNN correspondent Omar Jiminez spent an hour in custody after he was arrested live on television while covering the aftermath of protests in Minneapolis in May.

“Put us back where you want us, we are getting out of your way, just let us know,” he told police in riot gear as the camera captured his arrest.

CNN reporter Omar Jimenez arrested live on TV at Minneapolis protest

That same day, a local television reporter in Louisville, Kentucky covering unrest after the police killing of Breonna Taylor captured an officer appear to take aim and fire a pepper ball directly into her camera.

Photojournalist Linda Tirado, who recently testified to a congressional committee about police violence at protests, had pulled her camera away from her face for a brief moment while shooting images in Minneapolis when she was hit by what she believes was a rubber bullet.

The impact permanently blinded her left eye.

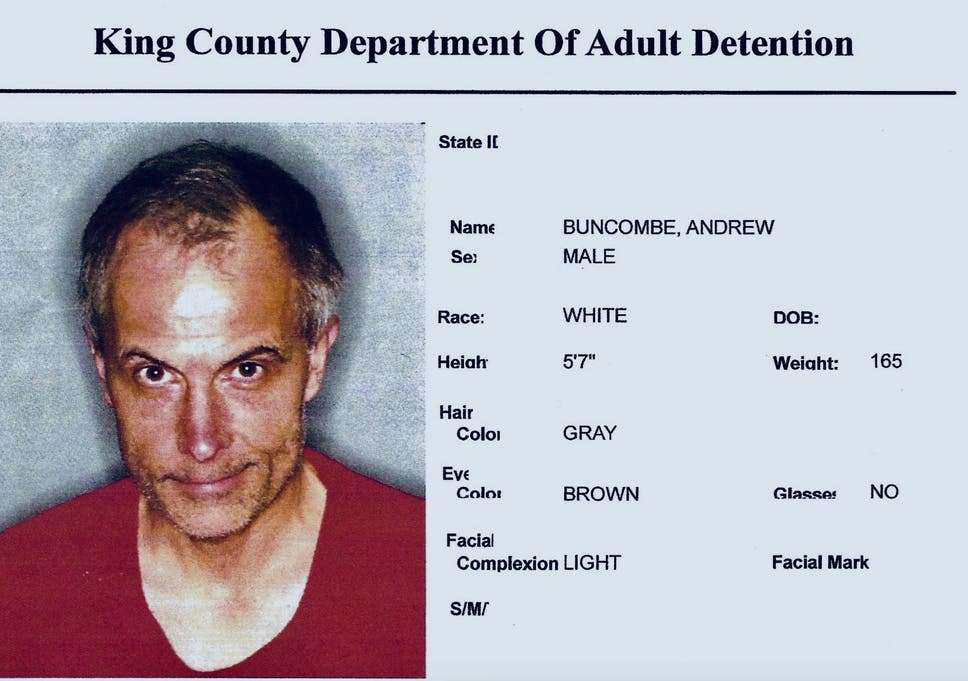

On 1 July Andrew Buncombe, chief US correspondent with The Independent, was arrested in Seattle while covering the police clearance of the so-called CHOP protest zone. He was charged with failure to disperse despite repeatedly identifying himself as a journalist and held for at least eight hours before being released.

As journalists continue to report police violence against them in the field, which press advocates argue underlines the diminishing trust among law enforcement for the news media, Donald Trump‘s message to his supporters remains the same.

The president has broadly derided journalists as “fake news” at his own press conferences while encouraging supporters at his rallies to mock the ”enemy of the people” in the room. Amid his 2020 re-election campaign fury on Independence Day, he attacked reporters as part of a “far-left fascism” staging a mutiny against him.

His attacks against the press have been derided as a creeping threat of authoritarianism, as arrests of journalists under his administration have begun outpacing those under authoritarian regimes.

In its 2019 survey, the Committee to Protect Journalists discovered that at least 250 journalists worldwide were jailed in retaliation for their work that year. Its annual survey found 255 reporters were jailed in 2018.

The highest number of journalists imprisoned in any year since the organisation began its annual survey was 273 in 2016.

But the numbers of arrests of journalists in other countries in 2019 pales in comparison to the number of reporters arrested in the US only halfway through 2020.

More than 60 journalists in the US have been arrested within the first six months of the year.

Last year, at least 48 journalists were jailed in China, followed by 26 in Saudi Arabia and 26 in Egypt, the organisation reported.

The US currently ranks 45th among 180 counties on the 2020 World Press Freedom Index by Reporters Without Borders.

The scale of attacks on journalists in the US has alarmed international human rights groups, which called on city and state officials and law enforcement to immediately halt the arrests of reporters and to appoint independent commissions to investigate assaults.

But by the end of the month, the number of attacks had increased nearly five times, after more than a month of nightly protests, vigils and other demonstrations against police violence and racial injustice.

“The importance of documenting these – and doing it as quickly as we can – is not lost: the conversations and reckoning that lie ahead of us as a country are taking shape right now,” Press Freedom Tracker managing editor Kristin McCudden said in a statement.

“No matter where we’re talking about it, the message is the same: what’s happened in 70 cities in more than 30 states across the nation in one month is unlike anything we’ve seen in modern history and surpasses the Tracker’s entire three-year history of documentation.”

Minneapolis has had 71 reported incidents against reporters, followed by Washington DC with 33, New York with 27, and Los Angeles with 20, the Press Freedom Tracker reports.

By the Fourth of July weekend, demonstrations had been going for more than 40 days, from memorials and rallies for victims of police violence to groups of people attempting to dislodge monuments to Confederates and slaveholders, including prominent US figures and former presidents.

Reporters used social media to capture several of these incidents, while news networks were devoting significant live coverage to protests in the first weeks of demonstrations and finding themselves targets.

CNN correspondent Omar Jiminez spent an hour in custody after he was arrested live on television while covering the aftermath of protests in Minneapolis in May.

“Put us back where you want us, we are getting out of your way, just let us know,” he told police in riot gear as the camera captured his arrest.

CNN reporter Omar Jimenez arrested live on TV at Minneapolis protest

That same day, a local television reporter in Louisville, Kentucky covering unrest after the police killing of Breonna Taylor captured an officer appear to take aim and fire a pepper ball directly into her camera.

Photojournalist Linda Tirado, who recently testified to a congressional committee about police violence at protests, had pulled her camera away from her face for a brief moment while shooting images in Minneapolis when she was hit by what she believes was a rubber bullet.

The impact permanently blinded her left eye.

On 1 July Andrew Buncombe, chief US correspondent with The Independent, was arrested in Seattle while covering the police clearance of the so-called CHOP protest zone. He was charged with failure to disperse despite repeatedly identifying himself as a journalist and held for at least eight hours before being released.

As journalists continue to report police violence against them in the field, which press advocates argue underlines the diminishing trust among law enforcement for the news media, Donald Trump‘s message to his supporters remains the same.

The president has broadly derided journalists as “fake news” at his own press conferences while encouraging supporters at his rallies to mock the ”enemy of the people” in the room. Amid his 2020 re-election campaign fury on Independence Day, he attacked reporters as part of a “far-left fascism” staging a mutiny against him.

His attacks against the press have been derided as a creeping threat of authoritarianism, as arrests of journalists under his administration have begun outpacing those under authoritarian regimes.

In its 2019 survey, the Committee to Protect Journalists discovered that at least 250 journalists worldwide were jailed in retaliation for their work that year. Its annual survey found 255 reporters were jailed in 2018.

The highest number of journalists imprisoned in any year since the organisation began its annual survey was 273 in 2016.

But the numbers of arrests of journalists in other countries in 2019 pales in comparison to the number of reporters arrested in the US only halfway through 2020.

More than 60 journalists in the US have been arrested within the first six months of the year.

Last year, at least 48 journalists were jailed in China, followed by 26 in Saudi Arabia and 26 in Egypt, the organisation reported.

The US currently ranks 45th among 180 counties on the 2020 World Press Freedom Index by Reporters Without Borders.

The scale of attacks on journalists in the US has alarmed international human rights groups, which called on city and state officials and law enforcement to immediately halt the arrests of reporters and to appoint independent commissions to investigate assaults.