Scientists discover surviving viruses in 15,000-year-old glacier ice on the Tibetan Plateau in China.

03 August, 2021

Credit: Lonnie Thompson, The Ohio State University.

Researchers find 28 surviving viruses from 15,000 years ago inside a glacier.

The viruses are not believed to be harmful to humans.

Researchers have found 15,000-year-old viruses in ice samples taken from the Tibetan Plateau in China, the majority of which are unlike any of the viruses currently known to science. The study, published in the journal Microbiome, could help scientists understand virus evolution and climate change.

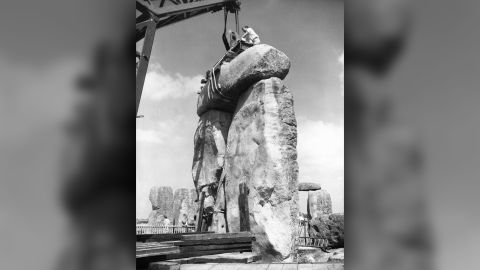

Two ice cores were collected in 2015 at extremely high altitudes — above 22,000 feet — from the Guliya ice cap in western China.

Lead author Zhi-Ping Zhong, a researcher at the Ohio State University's Byrd Polar and Climate Research Center, explained that the glaciers they examined were formed over a long period of time, collecting dust and gases as well as the viruses. "The glaciers in western China are not well-studied, and our goal is to use this information to reflect past environments," he said. "And viruses are a part of those environments."

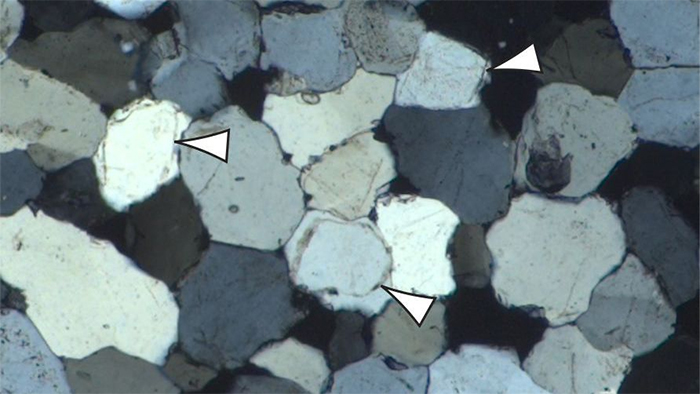

Poring over the samples, the scientists identified 33 viral genomes, 28 of which are novel and have not been described previously. Four of the known viruses infect bacteria.

Co-author Matthew Sullivan, professor of microbiology at Ohio State, said that these viruses were made for extreme conditions. "These viruses have signatures of genes that help them infect cells in cold environments — just surreal genetic signatures for how a virus is able to survive in extreme conditions," he stated.

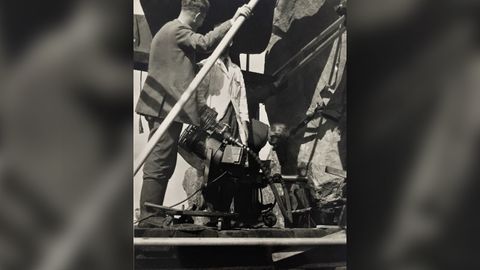

The ultra-clean method developed by the scientists to decontaminate the cores to study the microbes inside can be applied to samples taken from other harsh settings, like Mars or the moon. The technique involves stripping away the core's outer layer of ice. Then, the core is cleaned with alcohol and water.

Dangerous viruses in the ice?

Is it dangerous to dig up ancient viruses? Could they infect humans? Sullivan told Gizmodo that the viruses were made inactive by the "chemistry of nucleic acids extraction."

So, there's no need to worry this time. However, some researchers believe that the thawing of permafrost due to climate change could eventually release some viruses that might infect humans.

Watch a film on the ice core extraction in the Guliya glacier in 2015 -