The Unknown Masterpiece

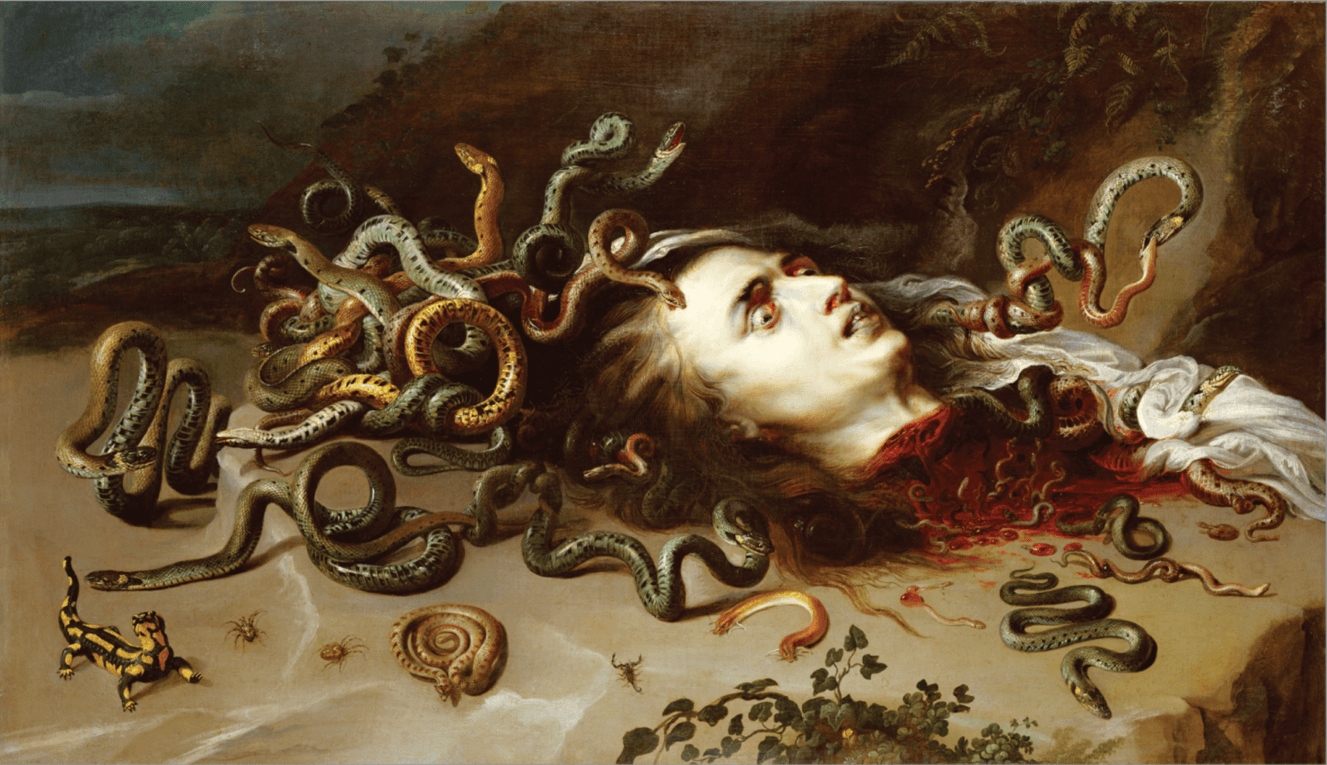

Follower of Otto Marseus van Schriek, Medusa’s Head, c. 1650, Uffizi Gallery, Florence.

Prologue

Many works of art are seen, but not written about. Only a few are written about but not seen. This essay is about the latter and ends with a discussion of a painting by the Italian artist, Luca del Baldo showing the murder of George Floyd. The picture should be approached with caution; like Medusa’s head illustrated above, it can turn to stone anybody who sees it.

The Shield of Achilles

The earliest Western example of an unseen but well described artwork is Homer’s account of the silver shield of Achilles in Book 18 of the Iliad. The buckler is the product of the Greek god Hephaestus (his Roman counterpart is Vulcan) and was decorated in concentric rings. One circle showed the starry constellations, another featured farming scenes, still another dancing, and so on. A particularly notable section represented two cities, one experiencing peace and prosperity, the other war and want. Here’s part of Homer’s ekphrasis (literary description) of the latter scene, as translated in 1720 by Alexander Pope:

They fight, they fall, beside the silver flood;

The waving silver seem’d to blush with blood.

There Tumult, there Contention stood confess’d;

One rear’d a dagger at a captive’s breast;

One held a living foe, that freshly bled

With new-made wounds; another dragg’d a dead;

Now here, now there, the carcases they tore:

Fate stalk’d amidst them, grim with human gore.

And the whole war came out, and met the eye;

And each bold figure seem’d to live or die.(Pope translation, 1720)

Very vivid! Homer used his description of the shield to create a story within the story and offer listeners a moral lesson: You can honor the gods and have a good life or defy them and have a terrible one.

About two and a half millennia later, in 1817, the British, Neo-Classical sculptor John Flaxman took up what must have seemed the ultimate artistic challenge: Re-create Achilles shield in glit bronze. He had already depicted it in miniature in 1793, in an engraved illustration showing Thetis delivering arms to her son. Now a mature and celebrated artist, Flaxman returned to the subject, re-reading Homer’s text in Greek and in its English translation by Pope. He made lots of preparatory drawings and then set to work. After completing his design, he modeled the shield in clay and from that made a plaster cast. This he turned it over to the metalsmith, Philip Rundell, who refined it and made casts in bronze, silver, and silver-gilt. One cast was shown at King George IV’s coronation banquet. But the artistic result, it seems to me, is a disappointment – a repetitious parade of nearly identical nude men and women: fighting, cavorting, and playing music. The shield is more like a luxurious tchotchke than a token of antiquity. Maybe that’s because the very genius of Achilles’ shield was that it was unseen; it was designed for the mind, not the eye.

John Flaxman, The Shield of Achilles, c. 1823, The Royal Collection Trust.

In the mid 20th century, the English poet W.H. Auden imagined another “Shield of Achilles,” this one forged by the violence of modernity. According to the poem, the nymph Thetis looks past Hephaestus to see an antique world of peace and prosperity. But when she gazes at the shield itself, she witnesses a dark vision of the future:

Barbed wire enclosed an arbitrary spot

Where bored officials lounged (one cracked a joke)

And sentries sweated for the day was hot:

A crowd of ordinary decent folk

Watched from without and neither moved nor spoke

As three pale figures were led forth and bound

To three posts driven upright in the ground.

Auden wrote the poem in 1955 and might have been describing a concentration camp, a public execution, or the aftermath of a political uprising. He knew the horrors of World War II, the Holocaust, and Hiroshima, and in 1947 published a book-length poem called “The Age of Anxiety,” a title that soon became a shorthand for the paranoia, fear, and failure of the Atomic Age. The irony of Auden’s shield of Achilles is that it couldn’t protect anyone from those dangers!

Medusa’s Head by Leonardo da Vinci

The Renaissance biographer, Giorgio Vasari, tells us that Leonardo da Vinci, when he was a young man, painted for his father a shield with the severed head of Medusa. Not content with the usual woman’s-head-with-snakes-for-hair, the artist gathered “lizards great and small, crickets, serpents, butterflies, grasshoppers, bats, and other strange kinds of suchlike animals” and assembled them into gruesome chimeras that he used as models for Medusa’s hair and bloody neck. (To avoid being turned to stone, Medusa’s killer, Perseus, used a mirror to guide his sword.) The result was so disturbing, that when his father saw it, he shrieked in alarm and “fell back a step.” Noticing that, young Leonardo expressed satisfaction with his handiwork, and his father sold the painting to a merchant for a hefty price.

I doubt there ever was such a painting. Vasari was a storyteller as much as a biographer, and he was probably using the tale of Medusa to attest to Leonardo’s remarkable powers of observation and invention. The young artist produced an image of Medusa so powerful, Vasari was saying, that it set his father back on his heels (“tornando col passo a dietro”). And while Vasari never says Leonardo’s father was turned to stone, he was clearly alluding to Medusa’s power. Just as in English there is the expression “stone dead”, in Italian there is “morto freddo come un sasso [“dead cold as a stone”], well-known from its use by the early 19th-century poet Filippo Pananti.* Vasari was however, describing an unseen masterpiece.

Caravaggio, Head of Medusa, c. 1597, Uffizi, Florence.

The only physical traces we have of the painting are much later re-creations. Most are horrific. Two of them shown here are by Caravaggio (1597) and Rubens (c.1618), and the third, (at the top of this column), is by a follower of the Dutchman, Otto Marseus van Schriek (c. 1650). They are all quite different.

The Caravaggio most closely recalls Vasari’s text; it’s painted on canvas attached to a wooden shield and is startling in its verisimilitude. However, unlike the female Gorgon of myth, Caravaggio’s has the features of the young artist himself, shown the moment his head is cut from his neck. Rubens’ painting, like the slightly later Dutch painting by a follower of van Schriek, shows the exsanguinated head of Medusa on a rocky outcrop, with the hair and blood turned into various, naturalistically depicted reptiles and worms. There are also water snakes,

Peter Paul Rubens, The Head of Medusa, circa 1618. Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna.

vipers, lizards, frogs, and salamanders, all painted with great verisimilitude. (Ruben’s frequent collaborator at this time, Frans Snyders, painted all his animals.) According to medieval legend, female vipers die giving birth because their offspring rip though her sides to escape. Vipers thus became emblems of ingratitude.

Rubens’ Medusa gazes down with horror to see the consequences of her own decapitation. And she will be responsible for more mayhem in the future: Even her image on a shield can turn an attacker to stone. Thus, paintings of Medusa, whether by van Schriek, Caravaggio, Rubens, or anybody else, are always about the danger of looking. They are in one sense, painted to remain unseen; but in another, they attest to the right and necessity of the artist to look, regardless of risk. In 1648, Gianlorenzo Bernini made a remarkable marble sculpture of Medusa. In that instance, he turned the tables on Medusa, changing her to stone!

Balzac’s “Chef d’Oeuvre Inconnu” (“The Unknown Masterpiece”)

Honore de Balzac’s short story “The Unknown Masterpiece,” published in 1831 is the paradigmatic, modern tale of the artist-genius whose work is fated to be unseen, unknown, misunderstood, or disparaged. The story concerns a 17th C. artist named Frenhofer who’s unable to finish his masterpiece, a painting of the beautiful courtesan, Catherine Lescault, upon which he’d been laboring for decades. The problem is that he lacks a model as beautiful as his imagined subject and is therefore unable to bring “the secret of life” to the picture. He hopes to glimpse somewhere, if only for a single moment, a “beauty divine” to inspire the finishing touches.

Help arrives in the persons of Frans Porbus and Nicholas Poussin, the names of real artists renowned for their work at the court of Marie de Medici and later, Louis XIII and Cardinal Richelieu. (Poussin spent most of his career in Rome, working for the pope and other exalted patrons.) It’s young Poussin who offers the elder Frenhofer a solution to his problem: He’ll introduce him to his lover, Gillette, who is as perfect as any marble Venus, if Frenhofer agrees to show Porbus and Poussin his unseen masterpiece. At first, Frenhofer rejects the deal with fury and defiance. To share his near-perfect Catherine Lescault — his adored companion all these years — with these inferiors would be a defilement. It was out of the question. But then Gillette stepped forward, “artless and childlike”, and Frenhofer was overcome: “’Oh, leave her with me for one moment,’ said the old painter, ‘and you shall compare her with my Catherine…yes – I consent.’”

The old painter and young Gillette withdraw behind the screen that hid Frenhofer’s unknown masterpiece from view. A few moments later, he reappeared and invited the other two artists within, exulting: “My work is perfect; I can show her now with pride.” But when Porbus and Poussin looked at the large canvas, what they saw was “confused masses of color and a multitude of fantastical lines that go to make a dead wall of paint.” The only discernable form was a bare foot, of a “living, delicate beauty.” At first, they doubted their eyes, then they suspected a joke, and finally they surmised the artist had gone mad. After a little while, Frenhofer realized he had ruined his masterpiece, and hastily rushed his companions out of his studio. The following day, Porbus returned to find Frenhofer dead after burning all his canvases.

The reason the story was so famous – imitated by Poe, Henry James, Emile Zola and Oscar Wilde, among others — is that it summarized many of the most salient debates about modern art: the contest between realism and idealism; the conflict between tradition and change; and artists’ constant need – in a capitalist society that craves novelty and fosters competition – to achieve new and superior effects. For the painter Paul Cezanne – who is reported to have said, “Frenhofer, c’est moi!” – the story was powerful because it addressed his anxiety about maintaining artistic coherence even as he cultivated his own, unique sensation. For him, as for Van Gogh, Matisse, Picasso and many others, painting was like walking a tightrope: You tried to be true to your vision and times, but were constantly at risk of falling into the chasm of incomprehensibility. And abstraction – which is what mad Frenhofer produced (apart from the beautiful foot) – was the feared eventuality. “At one time,” Vincent van Gogh wrote to his brother Theo in 1889, “abstraction seemed to me a charmed path. But it is bewitched ground, old man, and one soon finds oneself up against a wall.” At the time, he was painting works like Irises (1889, Getty Museum) in which flowers occupy almost the entire picture surface, flattening the space almost to the point of abstraction. Had he lived, he might have gone much further in his experiments, despite his fears.

As late as the 1950s, the Dutch-born, American artist Willem De Kooning experienced similar doubts. In his painting, Woman I and works that followed, he appeared to endorse Frenhofer’s paradoxical solution to the problem of coherence in the work of art: He painted the female figure but then disfigured it with “confused masses of color and a multitude of fantastical lines” until almost nothing recognizable was left, except the rudiments of a face, breasts and a pair of prominent pink feet.

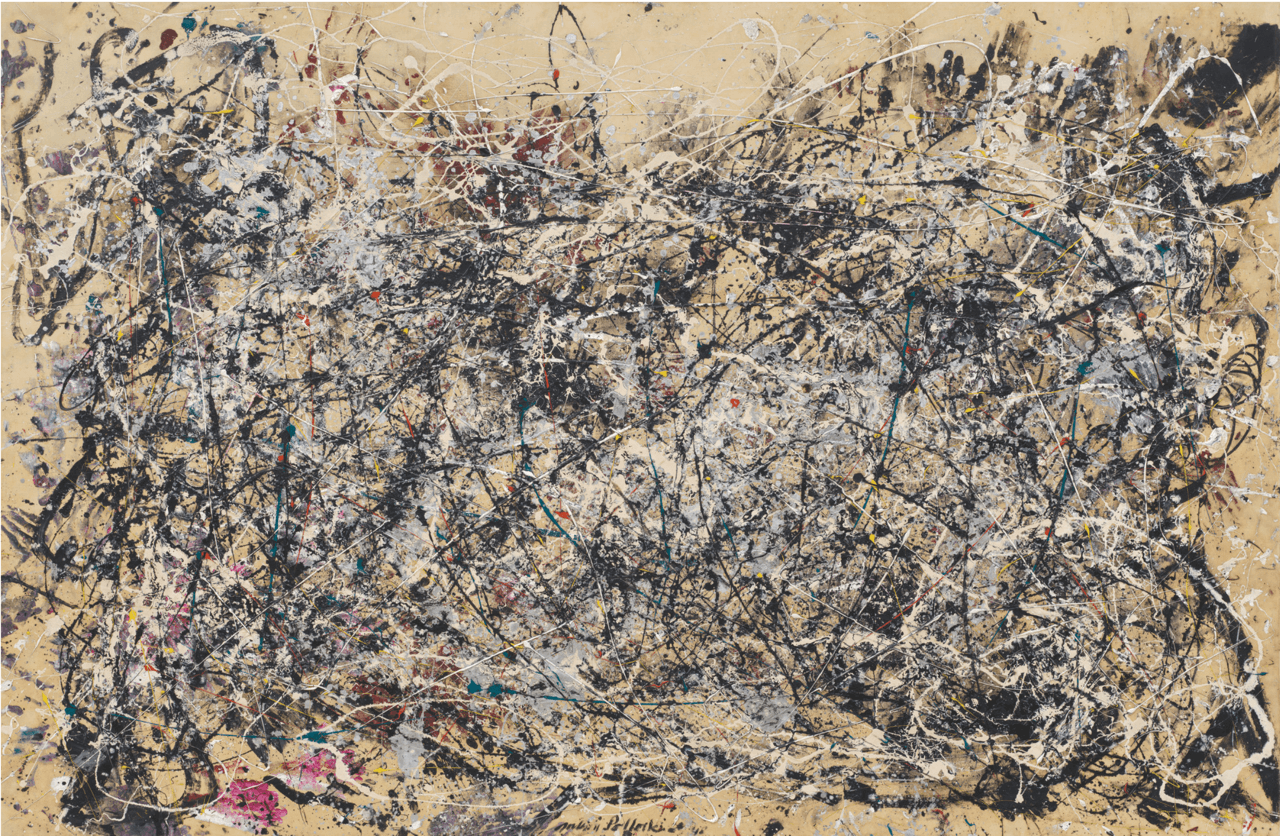

Jackson Pollock chased abstraction too, but without any of De Kooning’s doubts. He created archetypal images of the Age of Anxiety, and then dared everyone to look. “The modern painter cannot express this age, the airplane, the atom bomb, the radio,” he wrote, “in the old forms of the Renaissance or of any other past culture.” A good example of this is Number 1A, 1948 (1948), with an unrevealing title but an expressive surface animated by drips, pours, spills, and looping skeins of paint. At the upper right, handprints are visible, as if the artist was trapped within and desperate to escape. His painting is a nuclear blast.

Jackson Pollock, Nimber 1A, 1948, (1948). New York: Museum of Modern Art.

Luca del Baldo’s $20 Bill/George Floyd’s Murder

When the Italian artist, Luca del Baldo, learned of the murder of George Floyd in May 2020 following his arrest for passing a counterfeit $20 bill, the first thing he thought of was making a painting about it. That doesn’t mean he was insensitive to the horror of the crime, only that he thinks like an artist. Just as photo-journalists have an urge to capture the visually “decisive moment” in a narrative sequence, realist painters have the instinct to understand and depict remarkable people, places, and historical events. Unlike photographers, however, whose representational choices are mostly limited by what’s in front of their lenses, painters are free to re-arrange, distort, highlight, or obscure at will. They don’t even have to be witnesses to what they paint – they can use photographs, their imaginations, or previous artworks as their source material.

There are, of course, ethical limits to this freedom. Painters and sculptors can lie as much as writers can, and the consequences can be equally destructive – just think of all those stone or bronze monuments to perfidious Confederate soldiers and politicians. The challenge for realist artists then, is not just to create a plausible resemblance of something – a photograph or video can do that – but to reveal an underlying truth that has been overlooked or forgotten. That’s what Luca sought to do with his small triptych (three-part painting) of the Floyd murder, and why it’s so fraught an endeavor: The video of the killing has been seen so often, the outcry been so vociferous, and the consequent political change so minimal, that it’s hard to imagine a painting by an artist living thousands of miles from the crime, having much to contribute.

Luca del Baldo, $20 Bill/George Floyd’s Murder, 2020. Collection: The artist.

In fact, it’s worse than that: there’s a supposition by many that any representation of the subject by a white artist is at best gratuitous and at worst exploitative. That’s what several critics told del Baldo in letters or other communications – which is why the painting hasn’t been exhibited or published till now.

The most brilliant of these criticisms came from the cultural historian and philosopher, Ivan Gaskell, who wrote in late 2020, while protests raged:

It’s really not for me to suggest what you should decide regarding your painting of the murder of George Floyd, but since you ask, I’ll be candid.

I’m sure you have chosen this subject for good reasons, but I advise reflection–not that you are not always reflective. This is a moment that calls for extreme sensitivity.

You may want to revisit some of the things written at the time of the controversy about Dana Schutz’s painting, Open Casket, shown at the Whitney Biennial in 2017. White appropriation of extreme Black pain is the charge made then that resonates now. Hannah Black wrote then: ‘White free speech and white creative freedom have been founded on the constraint of others and are not natural rights.’ This is worth pondering, especially in the light of the realization, just dawning on many whites, that Black pain is inconceivable to those who [don’t] suffer it, despite all the empathy in the world. I never expected you to be anything other than thoughtful, and that’s the case. I certainly wouldn’t urge you not to make the painting, just to be circumspect about what you do with it….

The observations are sensitive and persuasive, though it seems to me they rely upon a mystification, “that Black pain is inconceivable to those who don’t suffer it.” The statement is unarguable, but for that reason fails to persuade. The pain of another is always inconceivable – that’s part of the meaning of pain — but we have all experienced sufficient physical hurt, grief, and loss to be able to fathom suffering and gain empathy. It is that very capacity that makes solidarity and collective action possible.

The triptych itself is easily described: It consists of a single, horizontal canvas, unequally divided into three, vertical sections. The largest in the middle, shows the knee of Minneapolis Police officer Derek Chavin pressed down upon Mr. George Floyd’s neck. A diagonal white stripe passes beneath Floyd’s nose and mouth. The fender and bumper of the police squad car intrudes at left, and Chauvin’s black boots are prominent at right. The scene at left shows the full figure of Chauvin crouched down beside the right rear of his car. As he holds his knee on Floyd’s neck, he gazes down at his victim with apparent nonchalance. His left hand is buried in his left trouser pocket as if to demonstrate how easy this is – “Look ma, no hands!” The streetscape here, with an open expanse of asphalt behind the assailant, appears different than in the larger, close-up view in the middle. In the right-hand section of the painting, Chauvin looks up at bystanders and us – he may be speaking. Once again, his left hand is in his pocket and sunglasses are perched on his forehead. So simple is this maneuver, Chauvin seems to say, and so well practiced, that I don’t even need to fold up my expensive sunglasses and cache them in my pocket.

These three perspectives on the murder of George Floyd were based upon frames from an eyewitness video by 17-year-old Darnella Frazier that went viral. Del Baldo works almost exclusively from photographs or stills, and in the past has depicted the dead bodies of Che Guevara, Muammar Gaddafi, and Pier Paolo Pasolini among others. But his style can’t really be described as “photo-realist” since his paint handling is quite free, and he allows himself distortions or exaggerations for expressive effect. The purpose of that combination of servility to the photograph and painterly freedom, broadly speaking, is to highlight the crisis of image-making in the age of late capital.

Mass-mediated images – photographs and video distributed through broadcast TV and personal computers – are chiefly the product of large, multinational corporations. That’s true whether the images are the creation of Disney or a grandmother on Facebook. In both cases, they are published for the purpose of generating revenue for the host companies, regardless of their beauty, ugliness, accuracy, falsity, tenderness, or promotion of violence.

At the same time, there exists another domain of images that provides the public real insight into the mechanisms of state power and capitalist control. These are produced by individuals, non-profit organizations, independent documentarians, and artists. Some of them, like the Floyd video by Daniella Frazier, expose crimes committed by public authorities, especially police. They are essential tools for dismantling oppression but are sometimes recontextualized by media organizations or the state in such a way as to lessen their power or persuasiveness. This act of appropriation and the resulting political and moral blindness it engenders, is what the art historian and critic Karl Werckmeister called the “Medusa effect.”

Rather than enabling activism, these mediated images freeze existing politics in place. That’s what happened to the George Floyd video. It was broadcast and rebroadcast so often, and in such varied contexts, that it lost its power to arouse or inflame. While it was essential evidence in the televised murder trial that convicted Chauvin, it lost its authority as a document of systemic, racial injustice. Police killings are just as high in the U.S as before the Floyd murder — about three per day – and far from being de-funded, police department budgets are increasing. That’s not due primarily to the vitiation of the Floyd murder video – it’s the result of multiple failures of vison and organization, and a sclerotic American political system. But corporate and state control of the media is a large part of the latter failure.

In $20 Dollar Bill/George Floyd’s Murder, Luca del Baldo challenges the “Medusa effect.” He does this by turning the murder scene into a triptych, akin to altarpieces by Flemish masters from the 15th century, including Jan van Eyck and Roger van der Weyden. He also draws upon Andactsbilder: initially German and Flemish paintings and sculptures from the late middle-ages that featured highly emotive religious subjects, usually the tormented or crucified Christ. These were later produced by Italian artists as well, including Andrea Mantegna, whose Lamentation of Christ is startling for its intense focus on the stone-cold body of Jesus.

Like Mantegna’s Christ, or Hans Holbein’s Body of Christ in the Tomb (1522), George Floyd is shown supine, and there’s no question that del Baldo would have us see him as a secular martyr. But what’s most remarkable about the painting is its focus not on the victim whose features are barely seen, but the criminal perpetrator, Derek Chauvin. I can think of no precedent for this in the history of art; it would be like showing a diminutive Christ between two large figures of Judas.

Andrea Mantegna, Lamentation of Christ, c. 1490, Pinacoteca di Brera, Milan.

The reason for this artistic decision, I think, is to deny the viewer the opportunity to mourn Floyd and experience catharsis, like viewers of Mantegna’s work were encouraged to do. Instead, we focus upon the criminal perpetrator, Chauvin, and are asked to gauge our own complacency concerning the racial violence on view. In this respect, the painting functions like Leonardo’s Medusa – it causes the viewer to “fall back a step.” Our inclination is to look away from the picture out of fear we may not feel sufficient shame, or that we may become “dead cold as a stone,” and fail to take the actions necessary to stop the killing.

* Many thanks to Steven F. Ostrow for his kind answer to my question concerning the Italian equivalent of the English expression, “stone dead.” Also see his: “Bernini and the Poetics of Sculpture: The Capitoline Medusa,” Arion – Journal of Humanities and the Classics, September 2021, pp. 15-32. Thanks also to Ivan Gaskell for permission to publish his personal communication and to Luca del Baldo for his answers to my questions.