Chartbook, Featured

June 9, 2022

The baseline scenario projects a slight re-acceleration 2023, but in the event of a severe Fed tightening, an energy embargo triggered by the war and continuing COVID issues in China, that number could fall to as low as 1.5 percent.

With inflation also running at record rates, comparisons are being drawn to stagflation of the 1970s. Heavy-weights like Larry Summers and Olivier Blanchard have been to the fore in warning that inflation is now so rapid that to bring it under control may require a draconian monetary policy intervention.

This may well prove alarmist. Not only are the data on the degree of inflationary momentum ambiguous, but in the debate so far they are drawn overwhelmingly from the US and Europe.

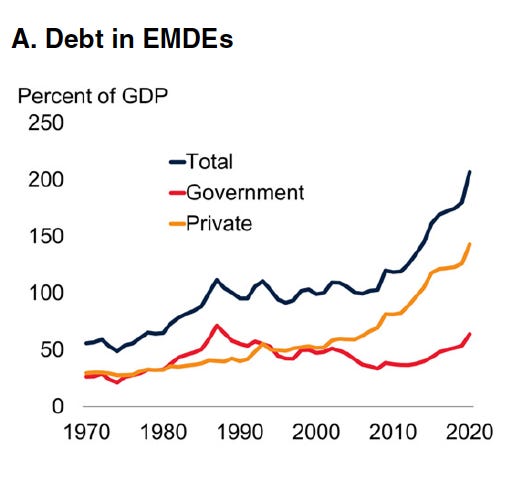

The World Bank in the latest report on Global Economic Prospects for June 2022 takes a broader view. In a Special Focus section they take on the theme of Global Stagflation and the comparison to the 1970s. Their analysis, they claim, is the first to provide a systematic comparison of the current juncture with the stagflationary period of the 1970s. The previous literature has mostly focused on a comparison of high inflation during that period with today’s inflationary challenges and studied the role of monetary policy and commodity price shocks in driving inflation in the two periods. This study considers the stagflation of the 1970s and examines the role of fiscal policy and broader structural differences in explaining weak output growth and high inflation. Second, in contrast to much of the earlier work, which has focused on the United States, this study presents a global perspective by examining the evidence of stagflation, and the challenges posed by it, for a broad set of countries.5 The threat of stagflation is global since the current combination of high inflation and weak growth is highly synchronized across many countries. Third, this Focus explicitly links the Emerging Market and Developing Economy debt buildup of the 1970s that culminated in the debt crises of the 1980s to the stagflation of that era and its eventual resolution in advanced economies. The 1970s witnessed the first global debt wave fueled by a prolonged period of accommodative monetary policies in major advanced economies. Since 2010, the global economy has been experiencing the largest, fastest, and most synchronized debt wave of the past five decades amid a protracted period of monetary policy accommodation. The study considers the lessons of the debt accumulation of the 1970s for the current debt wave.

As the World Bank remarks,

The current juncture resembles the early 1970s in three key respects: supply shocks and elevated global inflation in the near-term, preceded by a protracted period of highly accommodative monetary policy in major economies, together with recent marked fiscal expansion; prospects for weakening growth over the longer term, which echo the unforeseen slowdown in potential growth of the 1970s; and vulnerabilities in EMDEs to the monetary policy tightening by advanced economies that will be needed to rein in inflation.

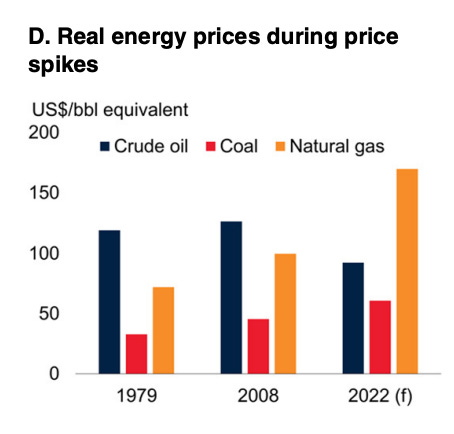

The energy price surge has rocked the entire world economy. In real terms the oil price shock of 2022 is in the same ballpark as 1979. The gas price shock is dramatically worse than anything previously seen.

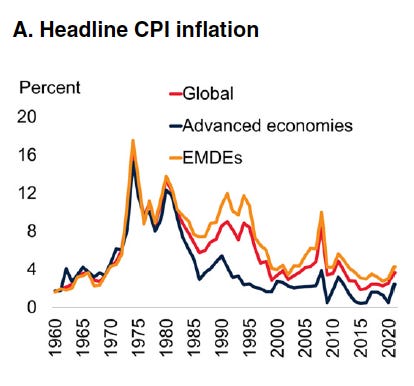

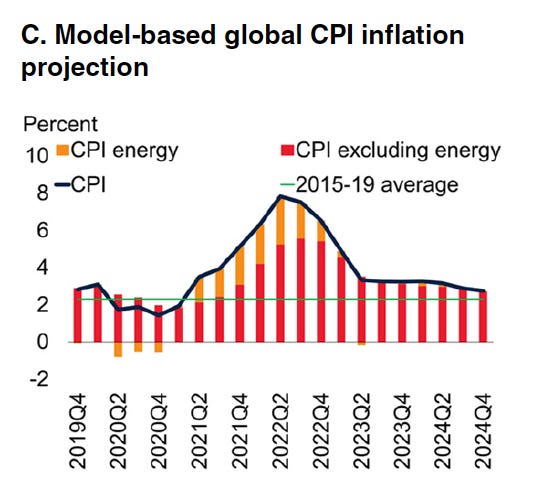

From a global point of view it is clear that though inflation has ticked up in recent months, following decades of lowflation, we are still a long way from the great inflation of the 1970s.

World Bank SF1.1 A.

In both the advanced economies and emerging and developing economies, the World Bank analysis shows that the drivers of inflation in 2021-2022 are a cocktail of supply constraints, a demand shock and a surge in oil prices. In neither the advanced economies nor the emerging market world, are supply factors – the famous supply-chains – clearly dominant.

And despite this variety of shocks, long-term inflation expectations so far remain anchored both in the advanced economies and in the emerging market world.

In the US, inflation expectations have significantly risen, especially over the 12-month time horizon. But they are no more than half the levels seen in February 1980.

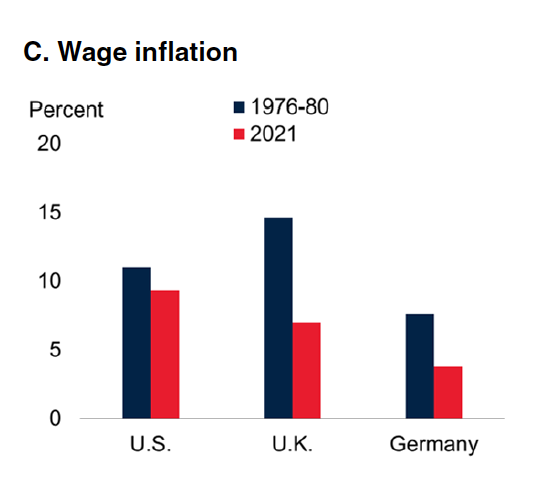

Wage inflation, which was a driver of wage-price spirals in the 1970s, is far more muted today, at least outside the US.

In the US, wage inflation is rapid, but remains behind price inflation, and, as the World Bank somewhat coyly remarks, in institutional terms there are huge differences between the 1970s and the present day. “Rigidities” are less pronounced, which is an unfortunate economist’s way of talking about the decline of organized labour and workers’ bargaining power.

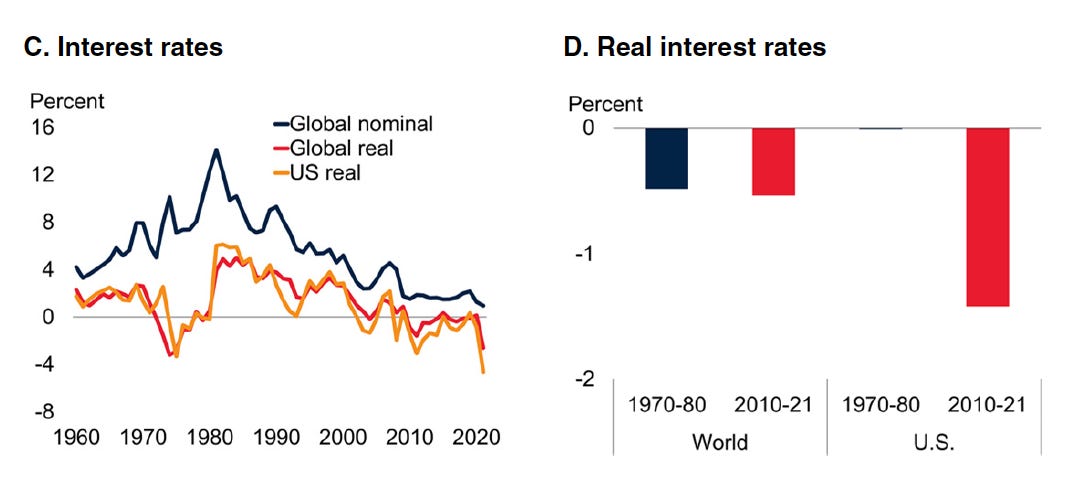

Part of the reason that markets are as relaxed as they are is, that if the Fed and the other central banks see fit to take action, they have plenty of scope to do so before needing to resort to Volcker-style shock therapy.

Right now, interest rates all over the world are in negative territory. In the US they are deeply so.

In the 1979-1981, the initial impact of the Volcker shock was simply to raise rates to the level of inflation. Then, as inflation rapidly slowed, interest rates surged to historic highs. We are a long, long way from that today.

What worries the World Bank is what happens if the Fed were to actually make use of its leeway to raise rates. Here too, the 1970s have lessons to teach. The World Bank’s worry is of a major emerging market and developing world debt crisis.

At that time, as the World Bank writes,

Low global real interest rates and the rapid development of syndicated loan markets encouraged a surge in EMDE debt, especially in Latin America and many low-income countries (LICs), especially in Sub-Saharan Africa. In Latin America, total external debt rose by 12 percentage points of GDP over the course of the decade while, in LICs, it rose by 18 percentage points of GDP. Much of this debt was in foreign currency and short-term, as capital flowed from oil exporters to EMDEs with large fiscal and current account deficits (figure SF1.5.C).

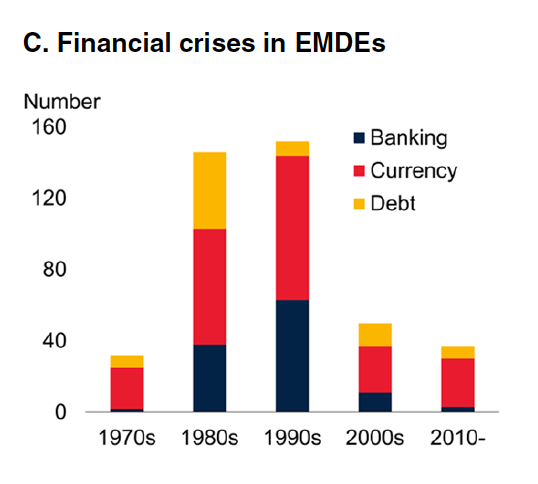

When the Volcker shock hit, it delivered a savage blow to emerging market borrowers, turning the 1980s into a decade of debt crises. The litany of financial crises in the 1990s was even worse, but now it was banking crises that were to the fore.

Despite COVID the number of emerging market and low-income country debt crises has never returned to the 1980s peak. But debt accumulation in the last fifteen years has been dramatic and a larger share of borrowing is susceptible to variable interest rates. From a share of c. 20 percent in the early 2000s, the variable rate component has risen to 35 percent.

Even if dollar interest rates are still a long way away from imposing a real squeeze, the dollar itself poses problems.

In the 1970s following the collapse of the Bretton Woods system, the dollar devalued. By contrast, since the start of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the dollar has strengthened sharply, exerting significant pressure on everyone who has borrowed in the currency, whether interest rate go up or not.

Those worst affected are emerging market and developing economies that are also commodity importers. They are being squeezed both by the appreciation of the dollar and the rise of commodity prices. And the bond markets are reacting. The spread paid by EMDE sovereigns that are commodity importers have surged by almost 250 basis points. Commodity exporters have seen a basis-point increase in their spreads of less than 100 points.

As far as the 1970s analogy in the advanced economies is concerned, the general impression conveyed by the World Bank’s analysis is that the similarities are more superficial than real. The World Bank expects global CPI inflation to fall back below 3 percent in 2023.

But the real question is what price will the world economy pay? As far as emerging market and developing market debt is concerned, the burden is far larger than it was in the 1970s. So too, of course, is the sophistication of their governance institutions. What Daniela Gabor calls the “Wall Street consensus” has sunk deep roots. The much-feared global COVID debt crisis of 2020 failed to arrive. Instead the accumulation of new debt went on. We may get lucky. There may be no tapering disaster in 2022-2024. But the World Bank alerts us to where the most serious risks lie. Along with the distributional question in rich countries, the main focus should be on ensuring that the tightening in the global dollar system does not impose intolerable pressure on its weakest links around the world.

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/L2RUZRIKR3MI5V3JOL77NB747Q.jpg)

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/IM26Y7RZIN3FYMJBPYANDLFHZI.jpg)