Flood exposure and poverty in 188 countries

Nature Communications 13, Article number: 3527 (2022)

Absract

Flooding is among the most prevalent natural hazards, with particularly disastrous impacts in low-income countries. This study presents global estimates of the number of people exposed to high flood risks in interaction with poverty. It finds that 1.81 billion people (23% of world population) are directly exposed to 1-in-100-year floods. Of these, 1.24 billion are located in South and East Asia, where China (395 million) and India (390 million) account for over one-third of global exposure. Low- and middle-income countries are home to 89% of the world’s flood-exposed people. Of the 170 million facing high flood risk and extreme poverty (living on under $1.90 per day), 44% are in Sub-Saharan Africa. Over 780 million of those living on under $5.50 per day face high flood risk. Using state-of-the-art poverty and flood data, our findings highlight the scale and priority regions for flood mitigation measures to support resilient development.

Introduction

Globally, natural shocks are estimated to cause an average of over $300 billion in direct asset losses every year; this estimate increases to $520 billion when considering well-being (or consumption) losses1. While each country faces its individual set of natural hazards, including cyclones, earthquakes, or wildfires, floods are among the leading threats to people’s livelihoods and affect development prospects worldwide2. Especially in lower-income countries—where infrastructure systems, including drainage and flood protection, tend to be less developed—floods often cause unmitigated damage and suffering3. Recent disastrous floods in countries as diverse as Nigeria, Bangladesh, Vietnam, the United States, and the United Kingdom illustrate that the threat is a global reality. Rare, major floods and smaller, frequent events alike can revert years of progress in development4 and poverty reduction. Understanding the scale and distribution of risks is crucial for devising targeted mitigation measures and allocating adequate resources.

While the threat is already substantial, several ongoing trends could result in significant increases in flood risks in coming years. For a high-concentration climate change scenario, estimates from 11 climate models converge to the conclusion that flood frequencies in Southeast Asia, East and Central Africa, and large parts of Latin America could increase substantially by 21005. Even in an optimistic climate change scenario (RCP 2.6), sea levels are estimated to rise up to 0.55 m by 2100, putting especially large coastal cities at risk6. Land subsidence, often caused by unsustainable ground water extraction and drainage, has been shown to increase coastal flood risks at a rate four times faster than sea level rise7.

Flood risks are also driven by socioeconomic change, as the number of people, assets, and value of economic activities increase over time3. By one estimate, in the absence of risk-mitigating measures, socioeconomic growth could result in the absolute damages from flooding to increase by a factor 20 by 2100. Considering the compounded effect of these drivers in the world’s 136 largest coastal cities, one study has shown that population and asset growth, climate change, and subsidence are likely to contribute to a drastic increase in global average flood losses, from $6 billion per year in 2005 to over $60 billion in 20508.

Recognizing the severe impacts of disasters on socioeconomic development, many flood exposure assessments have been conducted at local and national scales, often leveraging the recent availability of high-resolution flood, asset, and population maps, enabling increasingly accurate risk assessments. Yet, local studies have focused predominately on high-income countries like the European Union, United States, and Japan, not least due to data availability and the large economic values at risk9,10. While studies exist for developing countries, attention is focused on large economic centers like Jakarta, Dhaka, Dar es Salaam, Accra, and Ho Chi Minh City11,12,13,14,15,16; few systematic assessments exist for the least developed countries and subregions, where floods are likely to have the most devastating impacts on livelihoods.

Overall, there is limited evidence on the global scale of flood exposure and how it relates to the incidence of poverty. Previous global flood risk assessments suffer from multiple limitations. By using global historical inventories of recorded flood events (e.g., from EM-DAT), studies have estimated exposure indicators at the country level17. Yet, the lack of data on the spatial distribution and coincidence of flood risk and populations means that this approach does not allow a robust estimation of exposure headcounts17,18. A more recent study documents the worrying trend of increasing flood exposure using satellite data for 2000 to 2018, though omits at-risk populations who remained unaffected during the study period and many events that remain undetected by the satellite observations19.

Studies that use relatively coarse (by current standards) spatial resolution flood hazard data tend to only represent major fluvial floodplains. This means they are unable to capture pluvial flood risk and flooding along secondary rivers, and thus drastically underestimate exposure3,5,20,21. One study projects that the global number of flood-exposed people will reach 1.3 billion by 205020, but our study shows that this threshold has already been exceeded by at least 39%. This illustrates the importance of high-resolution data to capture the highly localized nature of flood risks, and the tendency of people to avoid settling in the riskiest locations22. Other global studies have only focused on certain types of flood, rather than assessing the combined risks from fluvial floods (rivers exceeding their capacity due to excessive precipitation), pluvial floods (surface water build-up due to extended precipitation and insufficient drainage), and coastal floods (due to tidal or storm surges, or sea level rise)2,23,24,25,26,27. For instance, a recent study conducted a detailed global assessment of the risk of sea level rise to the world’s coastal population28, estimating that over 190 million people live in areas that could be inundated by sea level rise by 2100; but it does not consider inland flood risks. Other studies have only assessed risks for a subset of countries, falling short of full global coverage22. Most importantly, none of the existing global studies consider the intersection between flood exposure and poverty incidence, which is a crucial indicator for people’s vulnerability, resilience, and ability to cope with and recover from floods1. This study addresses these gaps.

We find that about 1.81 billion people, or 23% of the world population, are directly exposed to inundation depths of over 0.15 meters. This would pose significant risks to lives and livelihoods, especially of vulnerable population groups. The majority (1.24 billion) are located in South and East Asia, where China (395 million) and India (390 million) account for over one-third of global exposure. Low- and middle-income countries are home to 89% of the world’s flood-exposed people. Of the 170 million who face high flood risk and extreme poverty (living under $1.90 per day), 44% are in Sub-Saharan Africa. At least 780 million people face high flood risk, while living on less than $5.5 per day. We conclude that the number of people living in poverty and under severe flood risk is substantially higher than previously thought. Moreover, they are concentrated in vulnerable regions that face compounding risks from climate change, sociopolitical instability, and resource constraints that hamper effective risk management. By offering global, yet disaggregated, insights on flood risk exposure and poverty incidence, this study highlights the scale of the needs and priority regions for flood risk mitigation measures that can safeguard livelihoods and prevent prolonged adverse impacts on development.

Results

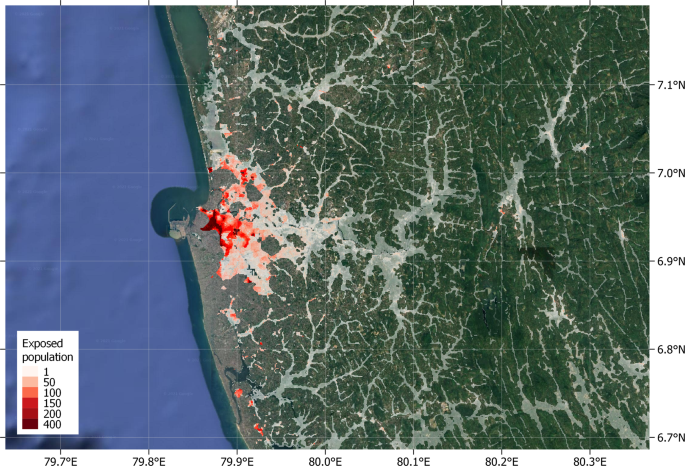

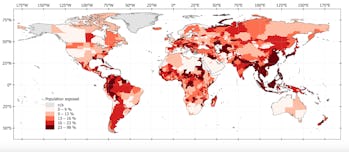

Here we present results from a high-resolution global exposure assessment for 188 countries, reaching within rounding errors of the entire world population. We assess people’s exposure to all current flood risks—that is, pluvial, fluvial, and coastal flooding. Flood data from Fathom-Global 2.0 are based on latest generation terrain and hydrographic models, while population density uses WorldPop 2020 maps calibrated on census and satellite data (Fig. 1). The global coverage of these datasets enables an overlay analysis with 3 arcseconds resolution (equivalent to about 90 × 90 meters at the equator), providing a more granular assessment than previous studies and eliminating the need for analytical assumptions besides the ones employed for producing the datasets. In addition, we use the latest edition of the World Bank’s Global Subnational Atlas of Poverty (GSAP), which harmonizes household survey data and offers poverty estimates with global coverage and statistical representativeness at the subnational level. Full technical details on data and computational process are provided in the “Methods” section.

Highlighted areas correspond to populated locations with significant flood risk as identified in this study. White highlights correspond to low population density, while red highlights show densely populated areas. Legend numbers denote number of flood exposed people per 3 arcsecond pixel. (Image: Google, ©2022 TerraMetrics).

Global and regional flood exposure

Our estimates show that globally, 1.81 billion people (23% of the world population) live in locations that are exposed to a significant level of flood risk, facing inundation depths greater than 0.15 meters in the event of a 1-in-100-year flood, or at least medium risk (Fig. 1). In other words, considering a global population of 7.9 billion29, almost one in four of the world’s people are exposed to significant flood risk.

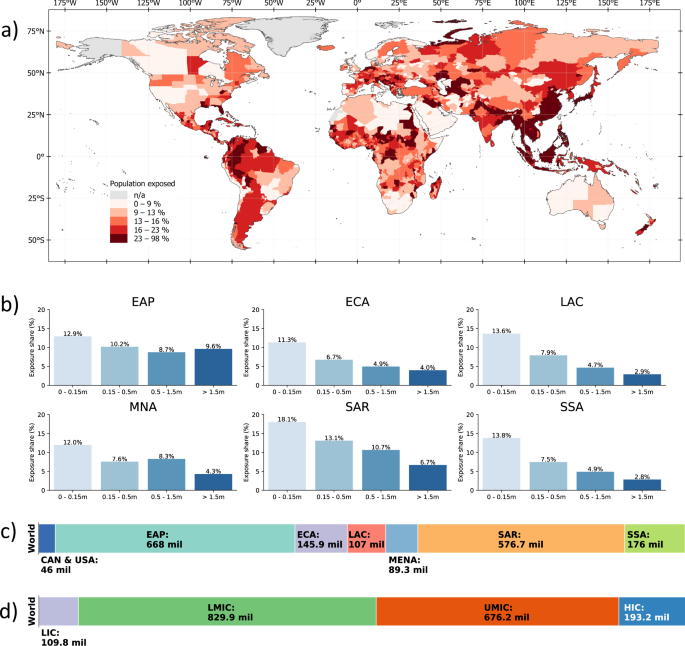

Regionally disaggregating global exposure headcounts, it becomes apparent that flood risks are particularly prevalent in certain regions. At 668 million people, the East Asia and Pacific region has the highest number of people exposed to significant flood risk, corresponding to about 28% of its total population. In the South Asia region, 576 million people are exposed to significant flood risk (about 30.4% of the population). Between 9–20% of the regional populations of Sub-Saharan Africa, Europe and Central Asia, Middle East and North Africa, Latin America and the Caribbean, and the United States and Canada are exposed to high flood risk. Figure 2 provides a full breakdown of regional exposure estimates in absolute and relative terms. In East Asia and Pacific, South Asia, and the Middle East and North Africa, regional exposure is driven by single countries, namely China, India, and Egypt.

a shows the percentage of population exposed to at least medium-level flood risk at the subnational level. b displays the percentage of population exposed to different levels of flood risk in each region. c, d show the total number of people exposed to at least medium-level flood risk based on geographical region and countries’ income classification, respectively. EAP East Asia and Pacific, ECA Europe and Central Asia (ECA), SAR South Asia region, SSA Sub-Saharan Africa, MNA Middle East and North Africa, LAC Latin America and the Caribbean, CAN & USA United States and Canada, HIC high-income countries, UMIC upper middle-income countries, LMIC lower-middle-income countries, LIC low-income countries.

Our results also show that 1.61 billion (89%) of the world’s flood-exposed people live in low- and middle-income countries and about 193 million (11%) live in high-income countries (Fig. 2d). Considering that flood-exposed populations in high-income countries are more likely to benefit from flood protection systems, social postdisaster assistance, and other risk management support, these figures highlight the significant risks faced by developing countries. Full country-level results are provided in Supplementary Table 1.

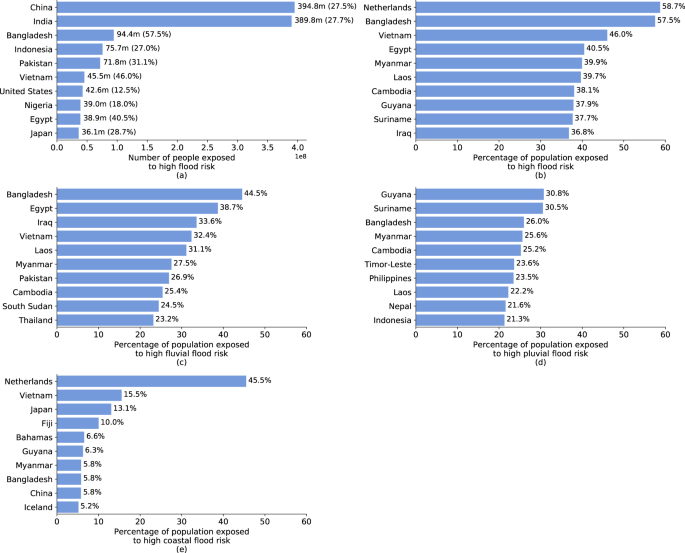

Countries with the largest flood-exposed populations

Several countries stand out with particularly large populations directly exposed to high flood risk (Fig. 3a); and several factors explain this picture. Evidently, more populous countries are more likely to have large numbers of people living in direct exposure to flood risk. The two most populous countries, India and China, have the highest absolute exposure headcounts with 390 million and 395 million, respectively, and account for about one-third of all people exposed to flood risk globally. Yet, geographical features and urbanization patterns can drastically increase the size of exposed populations. The top 10 countries in terms of absolute exposure headcounts feature countries in which large population groups are concentrated along major river systems (e.g., Bangladesh, Egypt, Vietnam) or in coastal regions (e.g., Indonesia, Japan).

a shows the ten countries with highest absolute number of people exposed (and as a percentage of the total population in parentheses). b shows the ten countries with highest relative population exposure. c–e show the ten countries with highest relative population exposure to different kinds of flood risks. Note: Countries or territories with populations of under 100,000 are omitted from this figure, in particular Andorra (24.3%, d) and Cayman Islands (6%, e).

However, focusing on absolute exposure headcounts risks overlooking countries with smaller populations yet large relative exposure. Figure 3b presents the top 10 countries in terms of percentage of population exposed to high flood risk, in all of which over one-third of the population is flood-exposed. The Netherlands has the world’s highest relative exposure to flood risk, with 58.7% of the population living in areas that would face inundation depths of over 15 cm in the event of a 1-in-100-year flood without considering flood protection systems. The country has some of the world’s most comprehensive flood protection systems, with protection against extreme events of up to 1-in-10,000-year return periods that can effectively mitigate the risks estimated in this study.

The same is not true, however, for most other countries with high exposure, particularly low- and middle-income countries, where flood risks coincide with poverty and vulnerability. Vietnam, where 46% of the population is located in flood zones, is a leader among developing countries in its efforts to mitigate natural risks. Its extensive sea dike system stretches over 2600 kilometers, exceeding many other countries’ protective infrastructure14. Yet the system is built to safety standards that only protect against 1-in-30-year coastal flooding, and would be overwhelmed by more severe events14.

Geographic and urbanization patterns are driving the high flood exposure relative to countries’ population size. Considering exposure to different flood types highlights these factors (Fig. 3c–e). Fluvial flood risks dominate in areas where large population shares are concentrated in low-lying river basins, such as the Brahmaputra (Bangladesh), Euphrates and Tigris (Iraq), Irrawaddy (Myanmar), Indus (Pakistan), Mekong (Cambodia, Laos, Vietnam), and Nile (Egypt, South Sudan). Pluvial flooding drives risks in mountainous regions where natural drainage capacity is more limited and flash flood risks are heightened (e.g., Nepal, Andorra), or in climates with intense rainy seasons that exceed drainage and soil absorption capacity (e.g., Bangladesh, Guyana, Myanmar, Suriname). Coastal flooding dominates in countries with expansive coastal urbanization (e.g., Guyana, Vietnam) and islands countries (e.g., The Bahamas, Fiji).

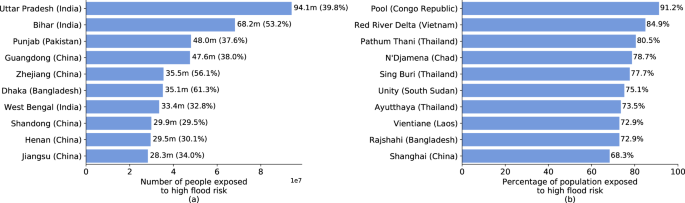

Flood exposure at subnational level

A spatially disaggregated view of flood exposure estimates highlights that, within countries, risks are concentrated in specific areas, such as the coast or river basins. Several subnational regions stand out with large, exposed populations (Fig. 4a). In the Indian states of Bihar, Uttar Pradesh, West Bengal—all located along the Ganges River—a combined 196 million people live in high-risk flood zones, accounting for 33–53% of the states’ respective populations. In Pakistan, ~48 million of Punjab’s 120 million people live in high-risk flood zones, corresponding to 38% of the province’s total population. Located at the confluence of the Ganges and Brahmaputra Rivers, almost two-thirds of the population of Bangladesh’s Dhaka Division are directly flood-exposed. In China, exposed populations are largest in provinces along the coast and Yellow River Valley.

While these are all large subnational regions that often exceed the size of smaller countries, our results show that in smaller subnational areas, much larger population shares can be at risk (Fig. 4b). The world’s top 10 subnational areas in terms of relative exposure are all in Africa and Asia. Pool Department in the Republic of Congo is located along the Congo River, and we estimate that 91% of its population of 360,000 faces significant flood risk. The subnational areas with highest relative exposure in Africa are Chad’s capital region N’djamena, on the Chari River, and South Sudan’s Unity State, on the White Nile. In three Thai provinces, all located along the flood-prone Chao Phraya River, 70–80% of the population are at direct risk. With about 85% of their population living in flood zones, Vietnam’s Red River Delta provinces have some of the world’s highest exposure rates, and are the country’s main population and economic centers.

Economic risk, poverty, and flood exposure

Using the World Bank’s global collection of harmonized household survey data, this study is able to highlight two seemingly contrasting findings: monetary flood exposure emphasizes risks in high-income countries; yet the interaction of flood exposure and poverty emphasizes risk in low-income countries. In short, by relying solely on monetary risk estimates, planners would bias their attention toward areas with high-value assets and large resources. But in so doing, they risk overlooking areas with high socioeconomic vulnerability, where flood risk mitigation measures are most urgently needed to protect lives and livelihoods.

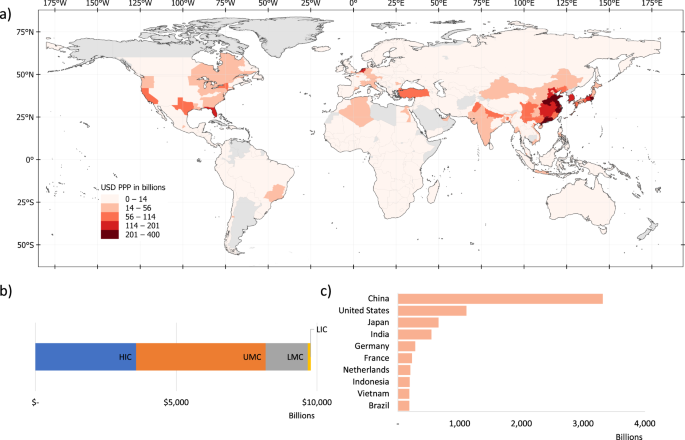

By combining the headcount estimates with per capita income levels, we translate flood exposure headcounts into estimates of the economic activity value that is directly exposed to flood risk. This monetary risk estimate suggests that $9.8 trillion of economic activity is directly located in areas with significant flood risks (note that this refers to exposed, not lost, economic activity, and does not distinguish people’s place of residence and work). This is equivalent to about 12% of global gross domestic product (GDP) in 202030. As Fig. 5 illustrates, monetary risk estimates highlight risks in higher-income countries, with the highest economic exposure in North America, Europe and East Asia, and Sub-Saharan Africa classified as having “low exposure” in monetary terms.

a shows the economic value at risk at an ADM-1 level. b displays the total economic value at risk for each region. c lists the top 10 countries with the highest economic value at risk. HIC high-income countries, UMIC upper middle-income countries, LMIC lower-middle-income countries, LIC low-income countries.

Of the $9.8 trillion of economic activity in flood risk areas, 84% is located in high- and upper middle-income countries (following the World Bank’s income classification). High-income countries account for 37% of exposed economic activity, but only 11% of the world’s flood-exposed population. In contrast, low- and lower-middle-income countries account for 52% of exposed people, but only 16% of exposed economic activity. Among countries with the largest economic value at risk, China leads, with $3.3 trillion exposed, followed by the USA ($1.1 trillion) and Japan ($0.7 trillion); no low-income country is among the top 10 countries in terms of economic value at risk. In interpreting these results, it is important to note that flood risk exposure does not account for existing flood protection measures. Such measures tend to be better developed in high-income countries, meaning that the fraction of exposed economic activity lost during a flood tends to be higher in low-income countries1.

Floods have been documented to cause more long-lasting and devastating effects in low-income communities. Here, lower-quality buildings and assets mean damages are higher1; inadequate planning and drainage infrastructure exacerbate hazards; the lack of widespread formal banking means people cannot draw on liquid savings or affordable credit to cope and recover; social systems lack the resources and reach they need to support affected populations; and insurance markets are less developed. To understand where flood risks pose the largest threat to development outcomes, a systematic assessment of poverty rates is essential.

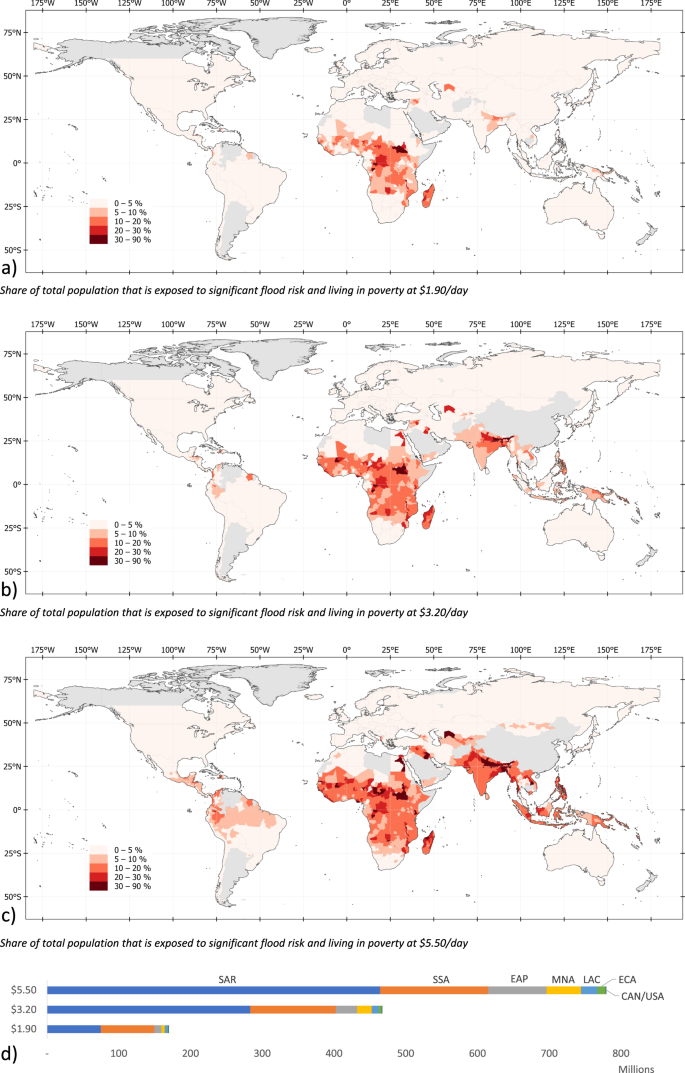

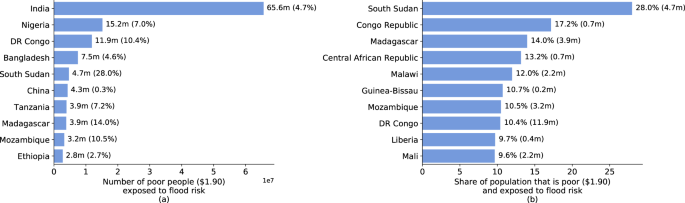

Our estimates show that of the 1.81 billion flood-exposed people globally, at least 170 million are living in extreme poverty (i.e., on less than $1.90 per day). Of these, 88% are located in Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia (Fig. 6). Flood exposure coincides with poverty most widely in Sub-Saharan Africa, where 74.7 million people are both flood-exposed and living in extreme poverty; in South Asia, the figure is also 75.0 million, driven by India (66 million).

a–c chart the share of total population exposed to significant flood risk and living with income below $1.90, $3.20, and $5.20 per day, respectively. d shows for each region the total number of people who are both exposed to significant flood risk and living in poverty. EAP East Asia and Pacific, ECA Europe and Central Asia, LAC Latin America and the Caribbean, MNA Middle East and North Africa, SAR South Asia region, SSA Sub-Saharan Africa.

The World Bank defines the $1.90 a day threshold as the most severe form of poverty, corresponding to a minimum subsistence level in low-income countries. However, floods are major livelihood shocks for all affected low-income households, even if they do not fall under the extreme $1.90 line. Hence, and given persistent poverty in middle-income countries, it is essential to consider less extreme poverty definitions. Indeed, when using less stringent poverty thresholds, the number of flood-exposed people in poverty increases significantly. We estimate that, globally, around 467 million people live in high-risk flood zones while living on less than $3.20 a day, increasing to 780 million if we consider incomes under $5.50 a day. This means that four out of every ten people exposed to flood risk globally are living in poverty (Table 1).

The maps in Fig. 6 highlight that raising the poverty threshold shifts the geographic concentration of poverty and flood exposure from mainly Sub-Saharan Africa to include subnational regions in Egypt, the Middle East, South and East Asia, and Latin America. Increasing the poverty threshold from $1.90 to $5.50 doubles the number of people in Sub-Saharan Africa facing flood exposure and poverty from 75 million to 151 million. In SAR, the increase is sixfold, from 75 million to 464 million; in East Asia, it is eightfold, from 10 million to 81 million.

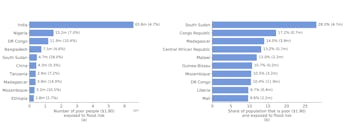

Among the top 10 countries where extreme poverty (at $1.90 threshold) and flood exposure coincide, seven are in Sub-Saharan Africa (Fig. 7a). With over 65 million, India has the highest number people exposed to flood risk and living in extreme poverty, though this represents only 16.8% of its total exposed population (390 million). As a share of the overall population, extreme poverty and flood exposure coincide most acutely in Sub-Saharan Africa (Fig. 7b); for these countries, 9–28% of the population faces significant flood risk while living in extreme poverty.

Overall, these results highlight that flood risks are substantial in many low-income countries. Our results also show that the risks are often concentrated in subnational regions within these countries—for example, there are provinces in South Sudan and Congo where over 50% of the population is both flood exposed and living in extreme poverty. Despite being typically overlooked by monetary measures of flood risk, these countries and regions face substantial vulnerabilities due to poverty and associated challenges surrounding social safety nets and infrastructure quality.

CONTINUE READING

Flood exposure and poverty in 188 countries | Nature Communications