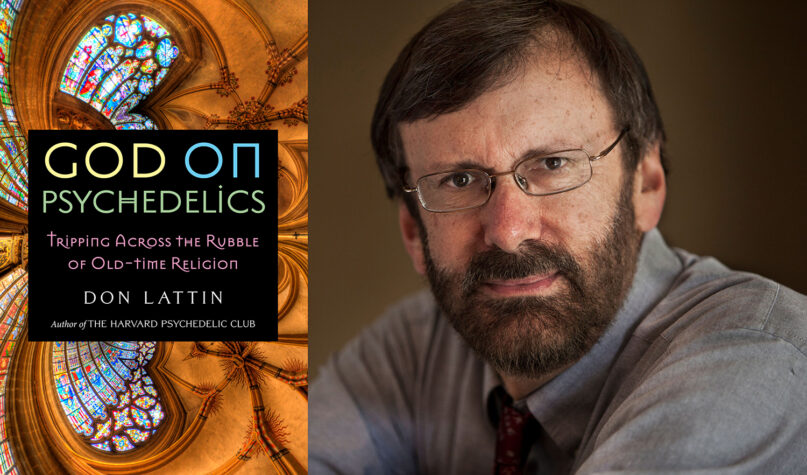

In ‘God on Psychedelics,’ Don Lattin offers a roadmap of congregational tripping

The veteran religion reporter investigates how various religious groups are using psychedelics to inspire chemically induced mystical experiences.

(RNS) — Decades after being forced underground by the war on drugs, psychedelics are going mainstream. Researchers are rediscovering the possibilities of using psilocybin, ketamine, MDMA and LSD as tools in treating depression, addiction and psychological distress.

Oh, and they may spark a spiritual awakening, too.

In his new book, “God on Psychedelics,” Don Lattin, a veteran religion journalist, investigates how some religious groups are encouraging chemically induced revelatory experiences of human interconnectedness and unity.

Lattin, who for years covered religion for the San Francisco Chronicle and has written six other books, mostly about psychedelics, said things are changing fast. Though mostly illegal for recreational use, universities around the world are studying psychedelics in clinical studies, and some states are taking notice: Oregon last year approved the adult use of psilocybin, the hallucinogen in “magic mushrooms,” though it is still hammering out the rules for its production and sale.

Five years ago, people — and particularly clergy — didn’t want to be quoted about their experiences with psychedelics. Now they’re far more open. Lattin said tripping is being explored in congregational settings and in chaplaincy.

RNS caught up with Lattin, who lives in the Bay Area, to talk about his new book. The interview was edited for length and clarity.

Your book introduces readers to the term entheogen — drugs taken for religious or spiritual purposes. Are psychedelics really God-enabling drugs?

They can be. “Psychedelic” means “mind-manifesting,” while entheogen refers to “the divine within.” I write about rabbis, priests and other clergy who do see entheogens as a way to renew the faith. Then there are the “nones” — people of no particular faith — who are consciously using psychedelics as a spiritual practice. Some are affiliated with new religious movements, including two originating in Brazil that use ayahuasca, a tea brewed from two plants native to the Amazon. A lot of ayahuasca or magic mushrooms churches based in the U.S. are underground, but some are going public as the legal situation shifts. They see sacred plant medicines as sacraments.

Another congregation I profile is called Sacred Garden Church. It seeks divine communion with different kinds of psychedelic drugs and sees itself as a “postmodern church” that follows the “path of least dogma.”

You point out that psychedelics don’t always induce feelings of unity with all humankind. They can also be terrifying, right?

Aldous Huxley, the famous British writer who wrote “Brave New World” and “The Doors of Perception,” called them heaven and hell drugs. They can give you a taste of heaven and they can send you right to hell, too. It really depends on the intention and context.

Even people who use these substances cautiously and carefully to open up to greater spiritual awareness or psychological insight may have very difficult experiences. You can have a bad trip. You can feel like you’re dying. You can feel like you’ve lost your body. You can feel you’re going crazy. These drugs can fuel feelings of unity, awe, compassion and gratitude. They can also induce paranoia, grandiosity and existential dread. But with an experienced guide, it can be fruitful. It’s like in therapy — trauma from your past can come up. Having someone help you through those feelings in a safe, contained environment can be really helpful.

It’s been eight years since scientists at New York University and Johns Hopkins University recruited clergy for a study to see if psilocybin deepened their spiritual lives. Will it ever be published?

It’s taking longer than most people thought, but researchers expect to publish a paper sometime this year. I tracked down four or five people in the study who were comfortable talking about their trips. Some people, like an Episcopal priest I write about, saw his psychedelic experience as “a second ordination” — for the first time, he felt the power of the Holy Spirit as bodily energy. Before, his faith was all in his head, too intellectual. Psilocybin inspired him to start an organization called Ligare, which is already having church retreats where other clergy can have these experiences. Currently, they can only do that in the Netherlands or a handful of other countries with less repressive drug laws.

But now Oregon and Colorado have legalized magic mushrooms and are regulating supervised psychedelic sessions. Under federal law, hallucinogens are only clearly legal in clinical trials or among churches that get a formal exemption, such as the Native American Church, or certain ayahuasca fellowships. But more than 20 cities in the U.S. have directed their police departments to stop arresting people for using certain types of drugs and plant medicines, so the legal situation is rapidly changing.

Is ‘mystical’ really the right word to describe the experience of psychedelic drugs?

Researchers have surveys they give people to measure if they had a mystical experience: Did you feel a sense of unity with the cosmos or with nature or other people? Did you feel awe and wonder? Mystical experiences are not always positive, but they’re profound, soul-shaking experiences that can crack people open. Then there’s the question as to whether psychedelics produce just altered states of consciousness, or whether they encourage altered traits of human behavior. Do they make us more aware and compassionate? I think that’s an important question, but not everyone does.

Mysticism itself can be dangerous to religious orthodoxy, no matter how it’s induced. The mystic often challenges the religious authorities of the time. That explains the hesitancy that many Christian leaders have toward mysticism, especially when it’s drug-induced. Some may also feel that it’s too much of a “short cut” to God.

What are the chances of finding a church that does psychedelics?

I bet you could, or at least a spiritual retreat center where you could experience this. Informed insiders estimate there are hundreds of these psychedelic churches. Some are very small — maybe a dozen people. Others may have 100 members. Then there are people who go down to Peru or Mexico or Brazil and work with shamans or indigenous medicine people and come back and start their own groups. Some are sincere. Others are charlatans.

There are several national networks of people lobbying now to reform drug laws. In Oakland, the city council passed a law a few years ago directing the police department to make these drugs their lowest priority. Sacred Garden Church came out of that local campaign. But this is not just happening in pockets of woke enlightenment like Berkeley, Boulder or Boston. There are big psychedelic churches in Utah, Arizona, Florida. It’s happening all over.

A lot of these new psychedelic churches keep certain Christian elements, right?

Yes. Take Santo Daime, one of the syncretic religious movements I profile in the book. It’s a mixture of folk Catholicism, spiritualism, African and Indigenous religion. You’ll see a Christian cross in their ceremonies, but also the Star of David. Many people in Santo Daime still consider themselves Christian or Catholic. What I found interesting was the large number of people in these groups in the U.S. who were raised Jewish. They probably wouldn’t call themselves “Christian,” but might say they are connecting to “Christ consciousness.”

You tried to join a couple of these psychedelic churches, but in the end, you went in a different direction. Describe the group you belong to.

“God on Psychedelics: Tripping Across the Rubble of Old-Time Religion,” by Don Lattin. Courtesy Lattin

It’s just a meditation group that I started working with about a dozen years back. We meet at a retreat house in Oakland run by a Catholic religious order. But it’s not Catholic. It has nothing to do with psychedelics. We employ a mix of contemplative prayer and Buddhist meditation. Many of us — but not all — are also involved in 12-step recovery groups. On some days, we’ll hear a dharma talk from a teacher from the San Francisco Zen Center who is also a recovering alcoholic. On another day, we’ll employ a lectio divina reading, perhaps a passage from the gnostic Gospel of Thomas, or a Rumi poem.

This is something I was already involved with before I started experimenting with psychedelics again as part of my research for my previous book, “Changing Our Minds — Psychedelic Sacraments and the New Psychotherapy.” I joined these psychedelic fellowships as a reporter, as a participant/observer who was sincerely open to the possibility of becoming a member. In the end, I decided none of them were for me.

I don’t really see psychedelics as a lifestyle. A lot of people may have one or two experiences with psychedelics. They will call it one of the most significant experiences of their lives. But it’s not like they want to do this every weekend, or even every month. I’m in that camp. There’s a famous line by the spiritual commentator Alan Watts, “Once you get the message,” he said, “hang up the phone.”

LA REVUE GAUCHE - Left Comment: Search results for PSYCHEDELIC