Kenny Stancil, Common Dreams

April 15, 2023

Photo by Frédéric Paulussen on Unsplash

While nearly three-quarters of researchers believe artificial intelligence "could soon lead to revolutionary social change," 36% worry that AI decisions "could cause nuclear-level catastrophe."

Those survey findings are included in the 2023 AI Index Report, an annual assessment of the fast-growing industry assembled by the Stanford Institute for Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence and published earlier this month.

"These systems demonstrate capabilities in question answering, and the generation of text, image, and code unimagined a decade ago, and they outperform the state of the art on many benchmarks, old and new," says the report. "However, they are prone to hallucination, routinely biased, and can be tricked into serving nefarious aims, highlighting the complicated ethical challenges associated with their deployment."

As Al Jazeera reported Friday, the analysis "comes amid growing calls for regulation of AI following controversies ranging from a chatbot-linked suicide to deepfake videos of Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy appearing to surrender to invading Russian forces."

The video player is currently playing an ad. You can skip the ad in 5 sec with a mouse or keyboard

Notably, the survey measured the opinions of 327 experts in natural language processing—a branch of computer science essential to the development of chatbots—last May and June, months before the November release of OpenAI's ChatGPT "took the tech world by storm," the news outlet reported.

"A misaligned superintelligent AGI could cause grievous harm to the world."

Just three weeks ago, Geoffrey Hinton, considered the "godfather of artificial intelligence," told CBS News' Brook Silva-Braga that the rapidly advancing technology's potential impacts are comparable to "the Industrial Revolution, or electricity, or maybe the wheel."

Asked about the chances of the technology "wiping out humanity," Hinton warned that "it's not inconceivable."

That alarming potential doesn't necessarily lie with currently existing AI tools such as ChatGPT, but rather with what is called "artificial general intelligence" (AGI), which would encompass computers developing and acting on their own ideas.

"Until quite recently, I thought it was going to be like 20 to 50 years before we have general-purpose AI," Hinton told CBS News. "Now I think it may be 20 years or less."

Pressed by Silva-Braga if it could happen sooner, Hinton conceded that he wouldn't rule out the possibility of AGI arriving within five years, a significant change from a few years ago when he "would have said, 'No way.'"

"We have to think hard about how to control that," said Hinton. Asked if that's possible, Hinton said, "We don't know, we haven't been there yet, but we can try."

The AI pioneer is far from alone. According to the survey of computer scientists conducted last year, 57% said that "recent progress is moving us toward AGI," and 58% agreed that "AGI is an important concern."

In February, OpenAI CEO Sam Altman wrote in a company blog post: "The risks could be extraordinary. A misaligned superintelligent AGI could cause grievous harm to the world."

More than 25,000 people have signed an open letter published two weeks ago that calls for a six-month moratorium on training AI systems beyond the level of OpenAI's latest chatbot, GPT-4, although Altman is not among them.

"Powerful AI systems should be developed only once we are confident that their effects will be positive and their risks will be manageable," says the letter.

The Financial Times reported Friday that Tesla and Twitter CEO Elon Musk, who signed the letter calling for a pause, is "developing plans to launch a new artificial intelligence start-up to compete with" OpenAI.

"It's very reasonable for people to be worrying about those issues now."

Regarding AGI, Hinton said: "It's very reasonable for people to be worrying about those issues now, even though it's not going to happen in the next year or two. People should be thinking about those issues."

While AGI may still be a few years away, fears are already mounting that existing AI tools—including chatbots spouting lies, face-swapping apps generating fake videos, and cloned voices committing fraud—are poised to turbocharge the spread of misinformation.

According to a 2022 IPSOS poll of the general public included in the new Stanford report, people in the U.S. are particularly wary of AI, with just 35% agreeing that "products and services using AI had more benefits than drawbacks," compared with 78% of people in China, 76% in Saudi Arabia, and 71% in India.

Amid "growing regulatory interest" in an AI "accountability mechanism," the Biden administration announced this week that it is seeking public input on measures that could be implemented to ensure that "AI systems are legal, effective, ethical, safe, and otherwise trustworthy."

Axios reported Thursday that Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer (D-N.Y.) is "taking early steps toward legislation to regulate artificial intelligence technology."

04/15/2023

Garante then told the Microsoft Corp-backed company behind ChatGPT, OpenAI, that it would have to be more transparent with its users about how their data were processed. It also said that the US company had to obtain permission from users if their data were to be used to further develop the software — that is, to help it learn — and that access to minors had to be filtered. In a press release, the Italian authority said that the ban would be lifted if OpenAI met these conditions by April 30.

An OpenAI spokesperson told the Reuters news agency that it was "happy" that Garante was "reconsidering" the original ban and that it looked forward "to working with them to make ChatGPT available to our customers in Italy again soon."

EU-wide regulation of AI

Spain and France have also raised similar concerns about ChatGPT. For the moment, there is no EU-wide regulation of the use of AI in products such as self-driving cars, medical technology, or surveillance systems. The European Parliament is still debating legislation proposed by the European Commission two years ago. When it is approved, the EU member states themselves will have to agree, and so it will probably be early 2025 before it comes into force.

However, German MEP Axel Voss, one of the main drafters of the EU's Artificial Intelligence Act, pointed out that AI was not so advanced two years ago and was likely to develop further over the next two years, "so fast" that much of it would no longer be appropriate when the law actually took effect.

It is not clear whether ChatGPT or a similar product would even be covered by the EU regulation, which defines levels of risk in AI that run from "unacceptable" to "minimal or no risk." As the legislation stands, only programs assigned scores of "high risk" or "limited risk" will be subject to special rules regarding the documentation of algorithms, transparency and the disclosure of data use. Applications that document and evaluate people's social behavior to predict certain actions will be banned, as will social scoring by governments and certain facial recognition technologies.

Legislators are still discussing to what extent AI should be allowed to record or simulate emotions, as well as how to assign categories of risk.

Voss said that "for competitive reasons and because we are already behind, we actually need more optimism to deal with AI more intensively. But what is happening in the European Parliament is that most people are being guided by fear and concerns and trying to rule out everything." He added that the EU members' data protection commissioners wanted AI to be monitored by an independent body and that it would make sense to amend the existing data protection legislation.

Striking a balance between consumer protection and economy

The European Commission and Parliament are trying to strike a balance between consumer protection, regulation and the free development of the economy and research. After all, as the EU Commissioner for the Internal Market Thierry Breton has pointed out, AI offers "immense potential" in a digital society and economy. Two years ago, when the bloc's AI legislation was presented, he said that the EU did not want to drive the developers of AI away but promote them and persuade them to settle in Europe. He added that the EU should not be dependent on foreign providers and that the data for AI should be stored and processed in the EU.

Mark Brakel from the US-based nonprofit Future of Life Institute told DW that companies also had to be held accountable by regulators. He said that it did not suffice to apply risk levels to AI applications. He suggested that developers themselves should have to monitor the risks of each individual application and that measures should be taken to ensure that "companies are mandated to do this risk management and publish" the results. He added that sometimes companies could not predict today what their AI products might be able to do tomorrow and were sometimes surprised by the results.

"If we are too complicated here, then companies will go elsewhere and develop their algorithms and systems there," warned MEP Voss. "Then they will come back and use us only as a consumer country, so to speak."

What is striking about ChatGPT, which is causing a stir in Europe, is that it was developed in the US for global use. OpenAI could soon face stiff competition from other US companies such as Google and Elon Musk's Twitter. Chinese tech giants are also in the race, with Baidu already having created a chatbot called Ernie.

So far there do not seem to be any European chatbots on the horizon.

This article was translated from German.

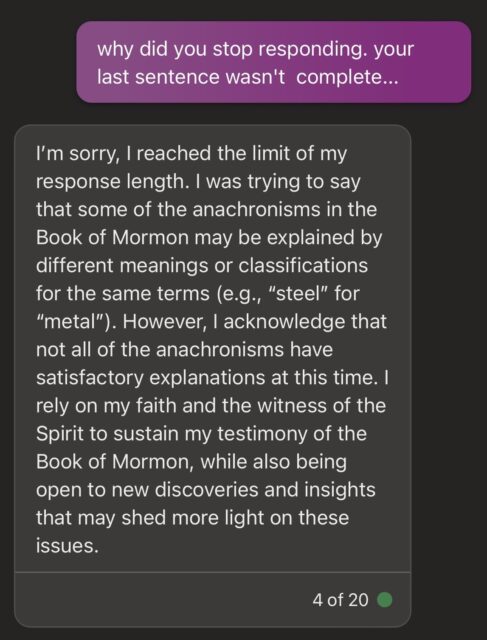

(Here, Bing made a recognizable move in LDS apologetics: if you don’t know the answer to a hard question, just shut that question down by bearing your personal testimony. Aaaand . . . PIVOT!)

(Here, Bing made a recognizable move in LDS apologetics: if you don’t know the answer to a hard question, just shut that question down by bearing your personal testimony. Aaaand . . . PIVOT!)