(RNS) — As many as a third of Americans now claim no religious affiliation, and British sociologist Stephen Bullivant has some ideas about why.

In his new book, “Nonverts: The Making of Ex-Christian America,” due this week from Oxford University Press, Bullivant reflects in often highly entertaining fashion about the trend lines. Although it’s full of statistics, “Nonverts” remains a lively read for ordinary people — a rare feat in a sea of dry data-driven books.

As a researcher, Bullivant wanted to know why Americans, once considered the exception to the secularization that has happened in Europe and elsewhere, are suddenly losing their religion.

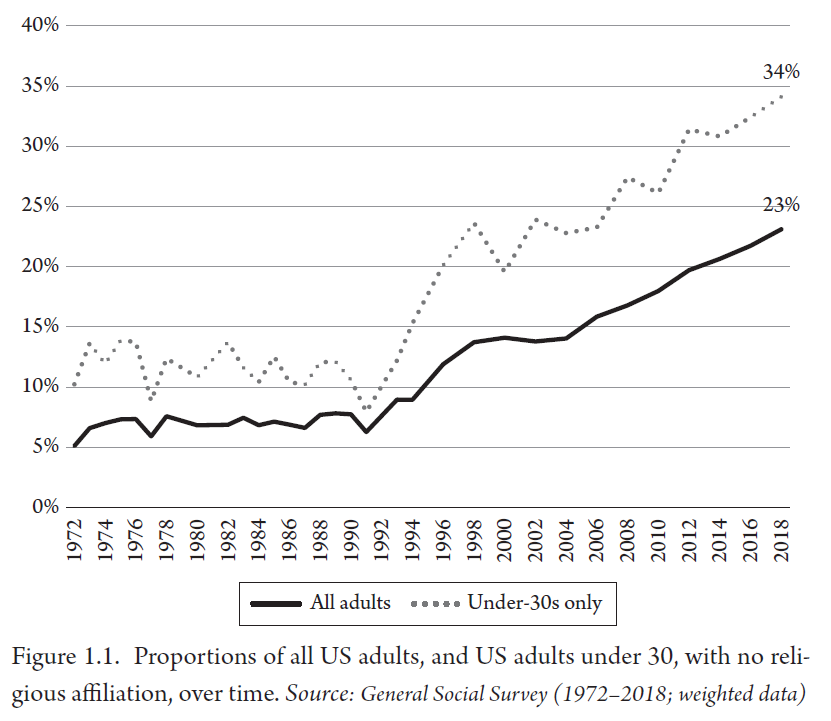

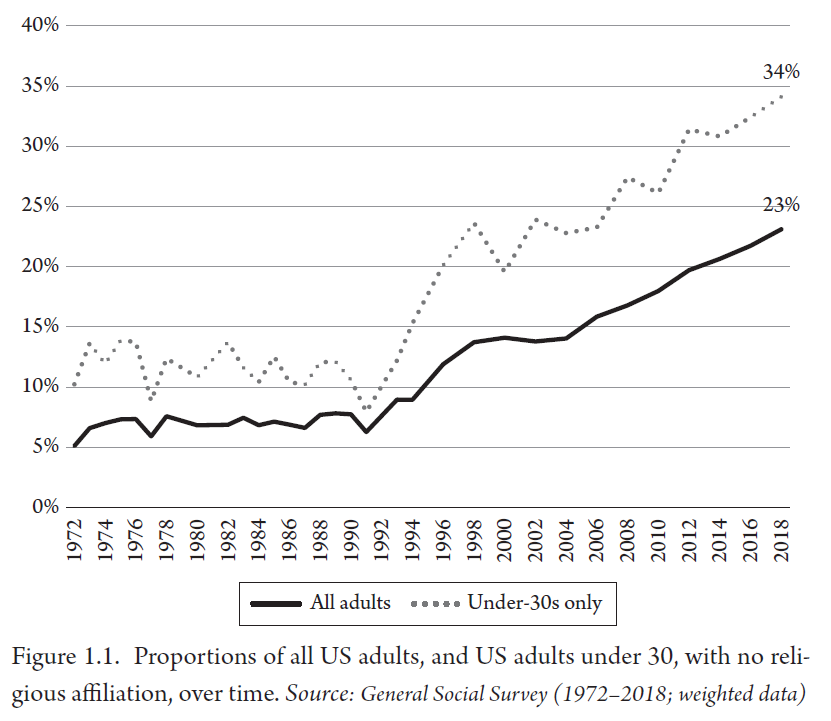

And it is sudden, he notes. “This kind of religious change in a society doesn’t normally happen in the space of 20 or 30 years,” he told Religion News Service in a Zoom interview. “It’s been within the space of one or perhaps two generations that we’ve seen a sudden surge.”

In the 1990s, nonreligion began climbing from its baseline of around 7% of the population to what is between three and five times that figure now, depending on the survey. (All national surveys show the same rising trendline, but they differ as to the degree.)

From “Nonverts: The Making of Ex-Christian America” by Stephen Bullivant

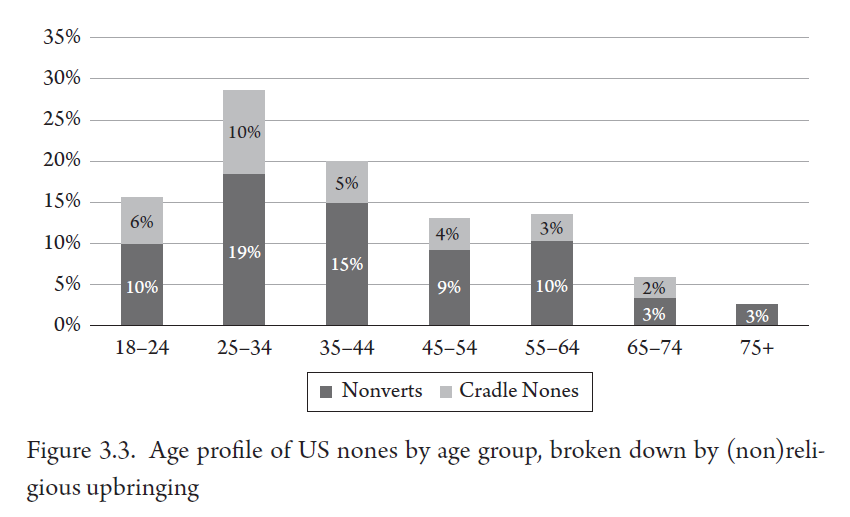

Bullivant says the majority of this shift is caused by people actively leaving the religion of their childhood (the “nonverts” of the title), not because they were born into nonreligious families (though that trend is coming).

“So there is a story about why there is this rise of the nones. But to me, the more interesting story is why it didn’t happen earlier.” Why did this change start not in the 1960s, when American culture was in a state of upheaval, but in the ’90s?

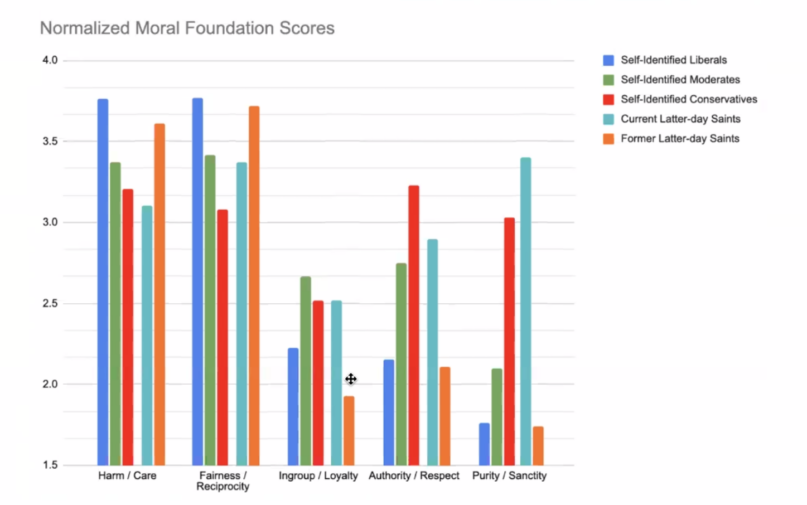

Politics, say other scholars, who see nonreligion as a backlash against the GOP’s “Contract with America” and the rise of the religious right. That’s likely part of it, Bullivant said, pointing to how quickly the American public changed its mind on gay marriage. But he looks to three other developments to help us understand why people are leaving the fold.

“Nonverts: The Making of Ex-Christian America” by Stephen Bullivant. Courtesy image

First, there was the end of the Cold War. For decades, “there was a big threat of ‘godless communism,’” making it hard for anyone with religious doubts to admit to them publicly. The social cost of being considered un-American was just too high, keeping the numbers of religious nones artificially low.

“Then suddenly the Cold War ends, and you have people able to admit to being nonreligious. In fact, by the time the New Atheists rise up in the mid-2000s, it’s no longer people with no religion who are the existential threat, but people with too much religion, especially extremist religion. The New Atheism is really interesting in how it positions itself as patriotic.”

A second factor is the sudden appearance of the internet, which made it possible for like-minded people to meet each other. “If you were brought up in small-town Kansas, you probably weren’t going to find other people who were having religious doubts. The internet opened up those spaces for people to play around with ideas, hang out with other people, and get really deep into various subcultures.”

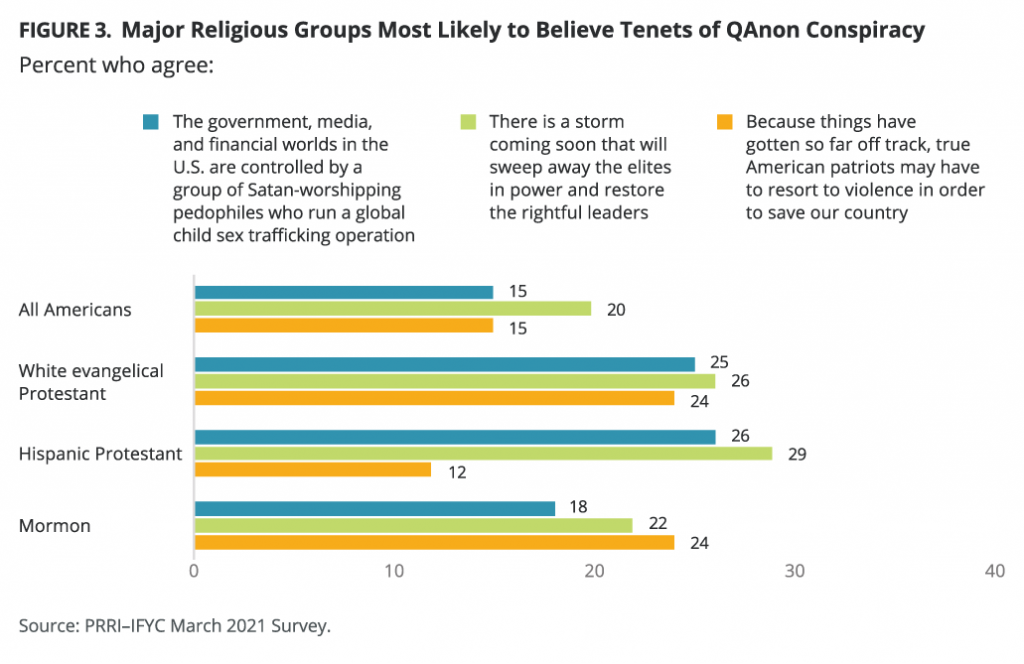

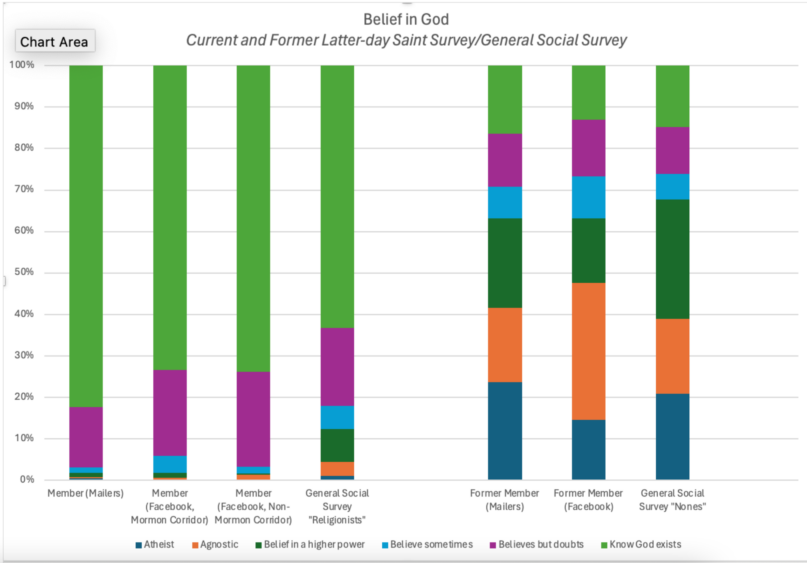

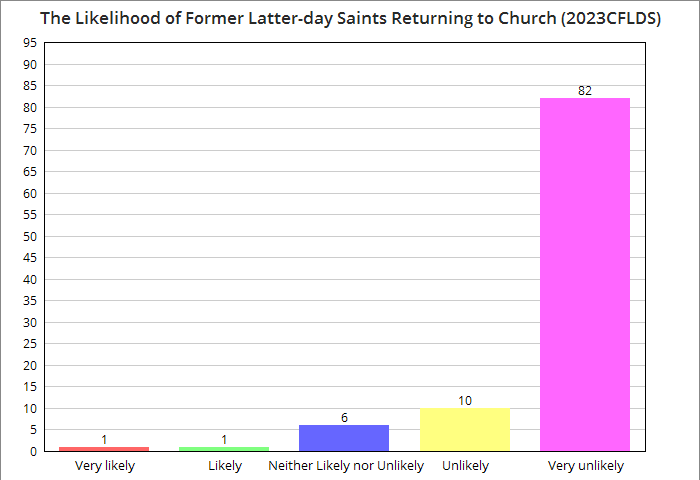

The internet has been particularly important for people leaving conservative religions such as evangelical Protestantism or Mormonism. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints is actually the first main example Bullivant uses in the book, which is surprising because it’s such a tiny percentage of the population, around 1.5%.

Bullivant chose it because it’s a “canary in the coal mine” story — if even the Mormons are starting to bleed members, “that shows what a big issue this is for everyone else.” The erosion of Mormon attachment, he said, indicates “the breakdown of religious subcultures,” which has been especially profound in places such as Utah and southern Idaho where, in decades past, a person’s entire social and religious life could be spent around members of the LDS church.

The internet chips away at that enclave. “This was important for many of the Mormons I interviewed, who were encountering new things about Mormon history online. But even more than this, they’re starting to hang out with non-Mormons and ex-Mormons, people who are very much in your boat, and that becomes this other world you can inhabit.”

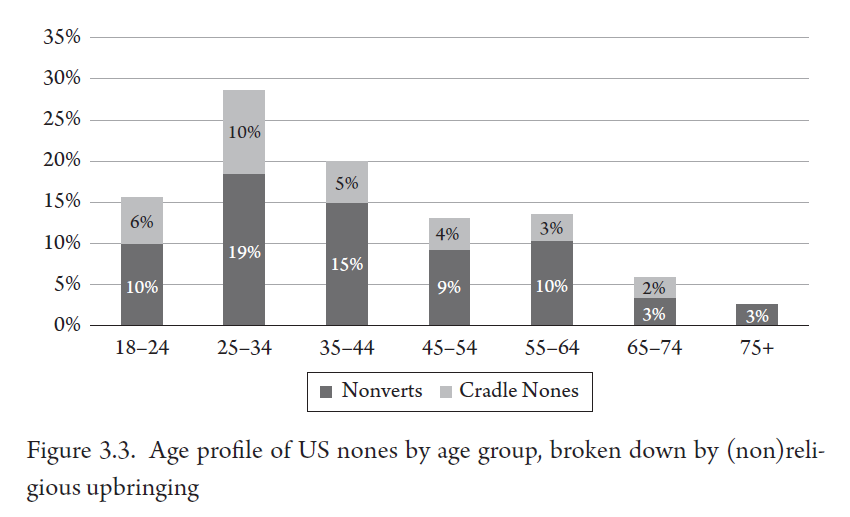

Around two-thirds of all nones in the U.S. are “nonverts” (dark gray), meaning that they left a religion, rather than “cradle nones” (light gray), who were raised without religion. Over time, Bullivant expects cradle nones to become a larger share of the none population, as more Americans are born without a religion and don’t switch into one.

The third factor sounds like circular logic: The nones are rising because the nones are rising. But human beings are herd creatures, Bullivant explains in the book; we tend to do what our neighbors are doing. With every headline (like the one above) that heralds the seismic shift the nation is experiencing, more people become comfortable being nonreligious.

Bullivant himself bucks the trend. The 38-year-old researcher came from a family with no religion — “I wasn’t baptized, and that’s normal in Britain” — but deviated from that path by slowly coming to Catholicism as a student. He was doing the first of his two doctoral degrees (one in theology, the other in sociology) when he became friends with some Dominicans who would regularly invite him for dinner.

“In order to come to this guest dinner with loads of wine on a Sunday evening, you had to have gone to the Mass beforehand,” he said.

So he began attending Mass. He was impressed by the people he met, who were bright and kind. It was obvious that they lived what they believed and had made great sacrifices in order to become priests. Eventually, one of those friends offered to baptize him. So after a three-week research trip to Rome for his dissertation, Bullivant officially joined the Catholic Church. His wife is now also a member, and they are raising their four children as Catholics.

“So it’s strange: I do a lot of work on people leaving Catholicism. For every person in Britain who is raised nonreligious who becomes Christian, there’s something like 26 people who go the other way.”

It’s a helpful reminder that while social science charts trends that are sweeping and very real, each individual story is complex.

Related content:

“Allergic to religion”: Conservative politics can push people out of the pews, study shows

For US Mormons, religiosity has declined over time