Lauren Almeida

Fri, 18 August 2023

Women affected by the increase in state pension age have been protesting for years - Jenny Matthews/Getty Images Contributor

More than 250,000 women born in the 1950s have died while waiting for state pension payouts in a draw-out campaign, it is claimed.

Until 2010, women were entitled to receive the state pension from the age of 60. The Government announced in 1995 that this would gradually increase to the age of 65 to bring it into line with men. Both ages now rise in tandem.

However, campaigners have argued women born in the 1950s, who were most affected by the change to when they could retire, were not given enough notice or detail.

Campaigners say around four million women were pushed into financial hardship as their retirement plans were knocked off course.

More than two-fifths of women in this generation have struggled to pay essential bills in the last year, the Women Against State Pension Inequality, or “Waspi”, group said.

The Parliamentary Ombudsman, the Government watchdog, ruled in 2021 that the Department for Work and Pensions had failed to provide clear communication around state pension age changes. However, it is yet to publish any recommendations for redress.

Angela Madden, who leads the “Waspi” campaign, said: “For the 250,000 women who have died while waiting for this issue to be resolved, justice delayed is truly justice denied.”

This equates to around 100 deaths per day, the campaign group said.

Ms Madden added: “The Ombudsman’s investigation has been going on for five long years, and it is two years since he confirmed the DWP was guilty of maladministration.

“To keep women waiting a single further day for a proper offer of compensation just shows an appalling disregard for all of us.”

Susan Taylor, a 65-year-old woman affected by the state pension age rise, said: “Both my sister and I were born in the 1950s and had our retirement plans completely devastated by the state pension age fiasco.

“I lost her at 59 to cancer and was diagnosed myself with lung cancer at 62. I have no quality of life and the financial pressures I face are immense. Some days it’s extremely hard to see anything but a miserable end to a lifetime of hard work as the fight for justice for so many women continues.

The Parliamentary Ombudsman was expected to publish the second stage of its investigation by the end of March this year, but was delayed indefinitely after a legal challenge to its original draft.

The final stage three of its report is expected to recommend possible solutions, however the High Court ruled in 2019 that the Government was right to correct “historic direct discrimination against men” and underlined that the ombudsman cannot reimburse “lost” pensions.

A spokesman for the Government said: “We support millions of people every year and our priority is ensuring they get the help and support to which they are entitled.

“The Government decided over 25 years ago it was going to make the state pension age the same for men and women. Both the High Court and Court of Appeal have supported the actions of the DWP under successive governments dating back to 1995 and the Supreme Court refused the claimants permission to appeal.”

A spokesman for the Parliamentary Ombudsman said: “We are confident that we have completed a fair and impartial investigation. As an independent ombudsman, our duty is to provide the right outcome for all involved and make sure justice is achieved.

“We hope this cooperative approach will provide the quickest route to remedy for those affected and reduce the delay to the publication of our final report.”

The state pension may no longer exist for these retirees

Lauren Almeida

Fri, 18 August 2023

gen z money

If you are under 40, the state pension will probably look very different by the time you retire. In fact, there is no guarantee that it will even exist.

Civil servants, industry experts and even some pensioners have been shouting for years: the state pension system is just too expensive for the Treasury to keep up. With ever larger payments to an ever growing number of pensioners, costs are spiralling out of control – and fast.

No political party wants to upset its oldest voters, but experts have warned the Government will have to change the way the system is set up or face a fiscal crisis.

In just 50 years, one in every four Britons will be pensioner age. That’s more than three times the current population of Scotland. And with birth rates in decline, less than two-thirds will be of a working age.

This is a problem because the state pension is a “pay as you go” scheme, which is fueled by general taxation. If there are more retirees and fewer workers, the system becomes more and more fragile.

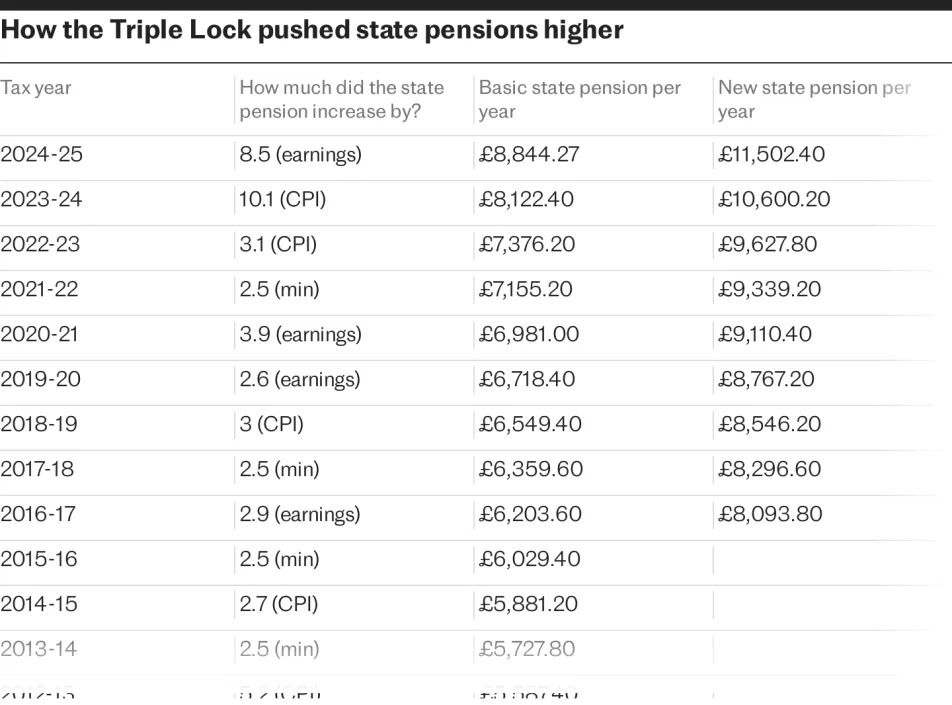

This is complicated further by the Conservative’s triple lock policy. It promises that state pension payments increase each year in line with the highest of the previous September’s inflation, wage growth or 2.5pc.

It meant this year the new state pension jumped by a record 10.1pc, surpassing £10,000 for the first time. Record wage growth is paving the way for yet another bumper pay rise next year, and will probably push it beyond £11,000 a year per person.

At some point, this will become unsustainable, but warning signs are ignored time and again. Even the Government’s own accountant warned that the “fund” that measures Britain’s state pension payments will hit zero in just two decades unless the Government acts.

The “National Insurance Fund” records workers’ and employers’ National Insurance contributions, as well as how much the Government spends on various benefits, including the state pension.

This “fund” is theoretical, as the Government can effectively deploy its financial resources as it sees fit. But it serves as a further alarm bell that while improving longevity is welcome, it is straining public finances.

Sir Steve Webb, a former pensions minister and now a partner at the consultancy LCP, said increasing the state pension age was a key “lever” the Government could pull to control spending.

“If you pay the state pension age later, then it pushes down costs,” he said. “This is a lever that the Government has pulled before and almost certainly will again.”

However, history suggests that increases to the state pension age would likely deepen social inequality. This is because there are stark regional variations in life expectancy, and poorer people typically have fewer private pension savings to fall back on and no choice but to stay in work for longer.

When the state pension age increased from 65 to 66, one in seven 65-year-olds were pushed into income poverty as a result, the Institute for Fiscal Studies found.

And while the Government typically waits for an increase in life expectancy to ramp up the state pension age, this does not necessarily correspond with an increase in healthy life expectancy.

Government expenditure on healthcare has been steadily climbing for almost a decade and the bulk of it goes towards curative and rehabilitative care, according to the Office for National Statistics. In just five decades, state pensions, pensioner benefits and health and adult social care spending will be worth 27pc of GDP, IFS analysis of official data found.

Maxwell Marlow, of the Adam Smith Institute, a think tank, said: “Young people are often criticised as wasting our money on avocados or Netflix. But the reality is that most of our taxes go towards spending on the elderly.

“The unfunded state pension system is shocking. It is a ponzi scheme grand enough to make Bernie Madoff blush.”

Around one in four pensioners are millionaires, so the idea of a means-tested state pension has gained popularity quickly. This could make for more targeted support for the vulnerable. Inequality in this group is stark, with around half of retirees also relying on the state pension as their main source of income.

Anyone who has more than £1m in assets should not receive a state pension, the Adam Smith Institute has suggested. “The triple lock is unfit for purpose,” its researchers wrote in a report last year.

“This ratchet spending is becoming unsustainable and unjustifiable, and exposes the Government to large state pension payouts which outstrip the growth of the economy that underwrites them.

“An increasingly large divide has opened up in British society between generations in which the young lose out, while the elderly benefit.”

According to the think tank’s calculations, the Government could save the taxpayer £25bn a year if it stopped offering the state pension to those with assets worth over £1m.

It said an alternative was to means-test pensions for higher-rate taxpayers – those with a salary of more than £50,270 – to avoid the “difficult politics” of testing those on lower incomes.

Sate pension increase

While scrapping the state pension completely may sound like the simplest solution, this too would require decades of advance planning, as well as warning for those who it would affect first.

But Sir Steve acknowledged that removing the state pension could become a more feasible option in the very long-term, after there had been a generation that had enjoyed the full benefit of “auto-enrolment”.

The policy, which obliges employers to automatically enrol their staff into a pension savings scheme, was only enacted around a decade ago.

“You would still need a safety net however for those who auto-enrolment had missed,” he said. “Across the world, you would be surprised about how many countries offer something that can be recognised as a type of state pension – even the land of the free has got it.”

But until we reach crisis point, it is unlikely that the Government will be spurred into action, Mr Marlow added.

“We are in a gerontocracy,” he said. “The civil service, the Treasury, the DWP – they all need to talk about these costs. The Government will not act until they are pinned to the wall.”

A government spokesman said there was currently a surplus of funds in the National Insurance Fund, and it would be able to top up its balance if needed in the future. They added it was committed to the triple lock and as is the usual process, would conduct an annual review of benefits and state pensions in the autumn.

Britain’s largest pension scheme to invest billions in private companies in boost for savers

Nest to invest up to a fifth of pension pots into high-growth businesses over next decade

Britain’s largest pension scheme will start investing billions of pounds in private companies in a boost to Jeremy Hunt’s plans to deliver higher returns for savers.

The National Employment Savings Trust (Nest), which looks after the retirement funds of a third of the British workforce, said it will invest up to a fifth of pension pots into high growth companies over the next decade.

Writing in The Telegraph, Mark Fawcett, Nest’s chief investment officer, said the move will offer most of its 12 million members the chance to enjoy “significantly higher” returns, with the risk spread over several decades.

He said: “We plan to step up our investment into private markets over the coming years, including more money into unlisted equities.

“Our view is simple – we don’t want Nest members missing out on an asset class which is so highly sought after.”

Mr Fawcett said Nest, the UK’s largest workplace pension scheme by members, would invest up to a fifth of younger members’ pension pots in private companies, which typically carry greater investment risk but can generate higher returns than publicly listed equities.

The policy is a significant vote of confidence in the Chancellor’s ambition to ramp up risk taking by pension funds to boost future retirement incomes.

Mr Hunt put pension reform at the heart of his Mansion House speech in July. The Chancellor wants the UK to rival countries including Australia and Canada that are home to huge pension schemes that invest in illiquid assets around the world, including in British infrastructure.

The risk-taking has led to higher rewards. Average annual pension fund returns in the UK were 9.5pc in 2021, according to Moneyfacts. This compares with a 20.4pc gain by the Canada Pension Plan Investment Board and 22.3pc increase delivered by AustralianSuper for the same year.

Defined contribution (DC) schemes like Nest promise a pension income based on the performance of stocks, bonds and other investments rather than a promise from an employer to sustain a certain level of income in retirement.

In July the Chancellor told an audience of bankers and finance bosses at the annual Mansion House dinner that nine of Britain’s biggest DC providers had signed a compact committing to invest at least 5pc of assets in unlisted equities by 2030.

Nest’s ambition to commit up to a fifth of assets for younger savers goes well beyond this. Mr Fawcett said there was “an especially large capacity to invest in these asset classes for our younger members,” who are decades away from retirement.

He said: “Those members have much greater ability to hold long-term illiquid assets compared to members approaching retirement, particularly when there are some assets which can be held in portfolios for decades.”

He added that “in the not-so-distant future” this could mean “a Nest member 40 years from retirement could have up to 20pc of their pension pot invested in unlisted equities”.

It is understood that Nest’s overall investment in unlisted equities, including private equity and infrastructure, will climb to at least 10pc of its portfolio by the end of the decade, potentially funnelling an extra £10bn into high growth assets.

Nest, which is publicly owned but operationally independent currently manages just over £30bn in retirement pots. This is forecast to balloon to £100bn by 2030. Mr Fawcett said this would give Nest the “size and scale to negotiate great deals” across a range of asset classes.

Mr Hunt has claimed that his compact with pension funds could help to boost retirement incomes by over £1,000 a year for a typical earner over the course of their career.

The Chancellor said: “British pensioners should benefit from British business success.

“This also means more investment in our most promising companies, driving growth in the UK.”

However, the Government’s own internal modelling suggests the very high fees charged by private equity firms could erase returns for pension savers.

High performance fees could even leave savers who invest in private companies £1,300 worse off, Department for Work and Pensions analysis showed.

Mr Fawcett insisted Nest did not pay performance fees “as a point of principle”.

He added: “All investment fits within our existing fee structure. This competitive fee structure also increases the probability that any net investment returns will meet our objectives.”

Why we’re investing Britain’s pension pots in solar farms and fish and chip shops

By Mark Fawcett, chief investment officer of National Employment Savings Trust (Nest)

The Chancellor’s Mansion House speech back in July generated a lot of interest within the pensions industry. Particularly the signing of the Compact by major UK defined contribution (DC) investors to commit 5pc of their portfolios to investing in unlisted equities.

There are questions from some quarters about whether UK DC schemes could, or even should, be investing in unlisted equities.

As a signatory to the Compact, our view is simple – we don’t want Nest members missing out on an asset class which is so highly sought after.

There’s a good reason private equity features in large pension schemes around the world. Average historic returns in private equity, broadly speaking, have been significantly higher than for listed equity over most time horizons.

At Nest, we’ve considered a wide range of factors and data to support our decision to invest in private equity because clearly, if we can achieve at least the average return, this will enhance the scheme’s total returns.

We’ve focused on growth-stage firms, as well as small and mid-cap buyouts, as these are the areas which we believe will deliver the highest risk-adjusted returns.

Since 2022, when we started investing in private equity, we’ve put money into a range of companies across industries.

One example is Captain D’s, a chain of seafood restaurants bringing a soul food take on the British classic of fish and chips for its American culinary audience. It’s been operating for 50 years but last year looked for further investment to help continue expanding its business.

Another deal Nest entered is in Sekhmet, the Indian pharmaceutical company, which is one of the world’s largest suppliers of generic drugs. Both very different companies, but both exciting investment opportunities.

Private equity assets bring an attractive combination of less volatile valuations and higher expected returns than their liquid counterparts. This combination is naturally desirable for any long-term, institutional investor.

We’ve also used our size and scale to negotiate great deals. As a point of principle, we don’t pay performance fees and all investment fits within our existing fee structure. This competitive fee structure also increases the probability that any net investment returns will meet our objectives.

The only difference our members should notice, now we’re investing their money into unlisted equities, are better risk-adjusted returns over the long term.

That’s why the debate of whether DC schemes should be investing in unlisted equities is somewhat over, or should be, provided those schemes have the scale and expertise to access good deals. The path ahead for growing UK DC pension schemes includes illiquids.

The conversation should be moving on to how best to include unlisted equities within a portfolio.

Having access to private assets is one thing, but can investment strategies be designed to maximise the benefit passed onto our members? Asset classes like private equity are still more expensive than their public market equivalents and it’s essential to select the right asset managers to ensure we generate value for money.

We think there’s an especially large capacity to invest in these asset classes for our younger members. Those members have much greater ability to hold long-term illiquid assets compared to members approaching retirement, particularly when there are some assets which can be held in portfolios for decades.

That opportunity is not just limited to unlisted equity. We think there are opportunities in other unlisted assets like infrastructure, not just in being hugely exciting investment assets but in how we can use them to connect with our membership.

Imagine telling a 22-year-old, who may be contributing into a pension for the first time, that when they start saving their money could be invested in infrastructure projects, like renewable energy – tangible assets they can see in the countryside around their home or just off the coast – for decades to come.

What a great message we can share with younger savers. That renewable energy will be powering their pension throughout their savings journey. A limitless source of energy making them money, while also increasing in value as we transition to low carbon economies.

Nest has recently updated its investment objectives and approach to strategic asset allocation. Within this is a new approach to better incorporate illiquids into our portfolio. We’ve evolved our investment glide pathway so younger savers have the highest percentage exposure, which then rebalances as they continue to save with Nest.

What does this look like in practice? That in the not-so-distant future, a Nest member 40 years from retirement could have up to 20pc of their pension pot invested in unlisted equities.

We plan to step up our investment into private markets over the coming years, including more money into unlisted equities. With our new investment objectives in place, we feel confident we can create the best outcomes for our 12 million (and growing) members.